13 Cancers of the female genital system

Epithelial ovarian cancer

Aetiology

Approximately 5–10% of ovarian cancer are familial, most of which are associated with BRCA1/BRCA2 gene mutations (90%) (p. 48). Women with a BRCA1 mutation have a 40% lifetime risk of ovarian cancer, and those with BRCA2 have an 18% lifetime risk. Women with HNPCC have a 10% lifetime risk of ovarian cancer.

Pathogenesis and pathology

Pattern of spread

The most common pattern of spread is peritoneal. Lymphatic dissemination to the pelvic and para-aortic nodes occurs in advanced disease. Spread through the diaphragm can lead to pleural effusion, although some effusions may be reactive. Haematogenous spread to the liver or lung is unusual (2–3%).

Investigations and staging

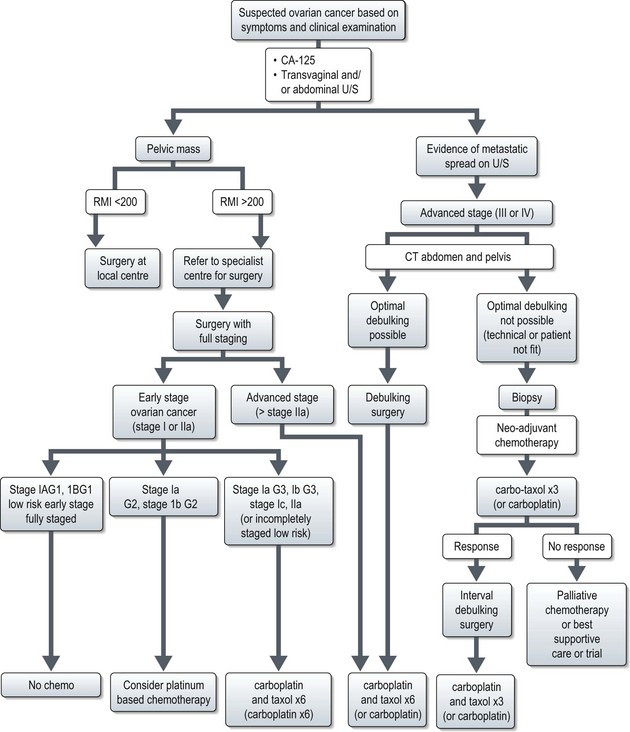

The risk of malignancy index (RMI) scoring system is used to predict whether a pelvic mass is malignant (Box 13.1). Women with an RMI of >200 should be referred to a specialist centre for further management and surgery. An RMI of >200 has a positive predictive value of 87% and a sensitivity of 88% for diagnosing malignant disease.

Box 13.1

Risk of malignancy index (RMI)

| Feature | RMI score |

|---|---|

| CA-125 | U/ml |

RMI score = ultrasound score × menopausal score × CA-125 level in U/ml.

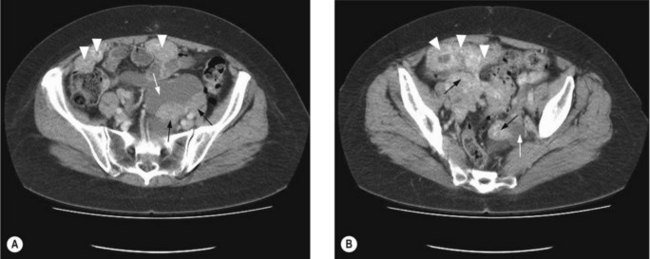

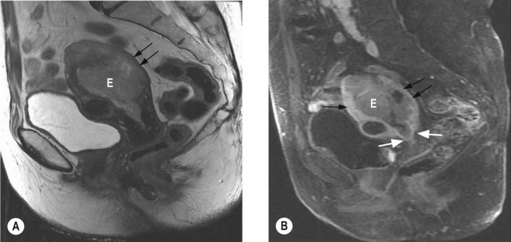

To assess operability patients should have a CT of the abdomen and pelvis (Figure 13.1), and a CXR. In patients with a pleural effusion, cytological diagnosis is required to determine if the effusion is malignant.

Patients with ascites without a mass on CT, should have cytological and immunohistochemical analysis, in addition to CA-125, CEA and CA19-9 (p. 287). The immunohistochemical profile of an ovarian tumour is typically CK 7 positive and CK 20 negative. A serum CA125:CEA ratio >25 is strongly suggestive of an ovarian rather than a GI primary.

Staging

The International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging is shown in Box 13.2.

Box 13.2

FIGO staging of ovarian cancer

Stage I – limited to one or both ovaries

Stage III – microscopic peritoneal implants outside of the pelvis; or limited to the pelvis with extension to the small bowel or omentum

Stage IV – distant metastases to the liver or outside the peritoneal cavity

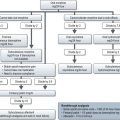

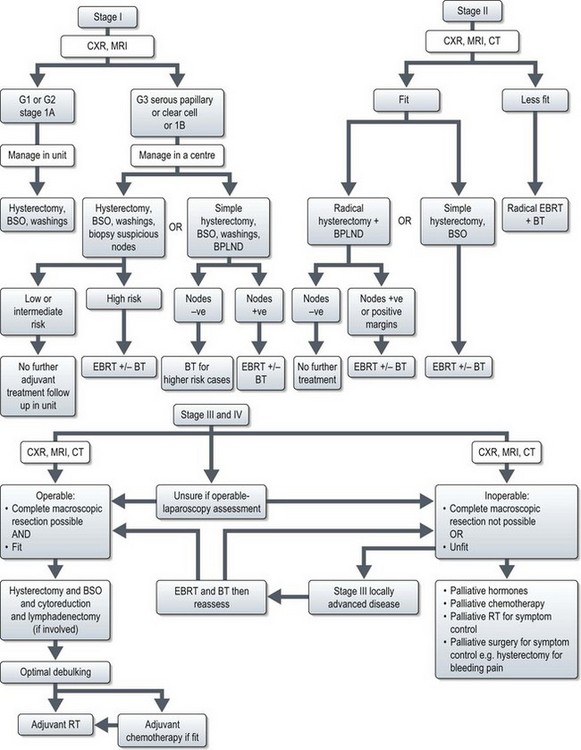

Management (Figure 13.2)

Early stage disease (stage I and II)

Surgery

Fertility preserving surgery

In younger patients with stage IA tumours and favourable histology, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging may be carried out, although data on fertility preserving surgery is limited. Endometrial biopsy should be carried out as a synchronous primary is present in 10% of patients. Wedge biopsy of the contralateral ovary should only be taken if it appears abnormal, as the probability of involvement of a macroscopically normal ovary is low (2.5%).

Chemotherapy

For patients with stage IA/B G1 non-clear cell cancer (low risk) 5-year disease free survival is >90% without chemotherapy if optimal surgery has been performed. For patients with high risk features (G3, clear cell, stage IIA disease), 5-year recurrence rates are 25–40% and adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended. In these patients, chemotherapy improves 5-year disease free survival (DFS) by 11% (from 65% to 76%), and 5-year overall survival (OS) by 8% (75% to 82%). Chemotherapy with 6 cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel is recommended, although 6 cycles of carboplatin is also acceptable (Box 13.3). For stage I G2 tumours the role of chemotherapy is not clear but 6 cycles of carboplatin may be offered.

Advanced stage disease (stage III and IV)

Patients with advanced disease may develop medical complications as a result of their cancer, notably thrombosis which has consequences for further management (Box 13.4).

Surgery

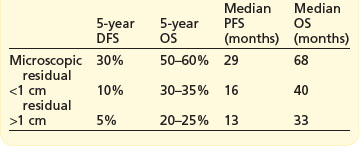

The extent of cytoreductive surgery is the most important prognostic factor after stage. The aim of surgery is to achieve a complete macroscopic debulking, or failing this, an ‘optimal debulking’. The definition of ‘optimal debulking’ is visible residual tumour of <1 cm. Studies have shown that patients with residual >2 cm show no improvement in survival over patients without debulking, and are considered incurable. Outcomes according to cytoreductive surgery are shown in Box 13.5. However, even after a complete response 25–50% will recur later.

Prognosis

Prognosis according to stage is shown in Table 13.1. The most important prognostic variables after stage are in order; degree of differentiation, cyst rupture, substage of disease and age.

Table 13.1 Prognosis of ovarian cancer

| FIGO stage | 5-year survival (%) | 5-year disease-free survival |

|---|---|---|

| I | 80–90 | 70–85 |

| II | 65–80 | 55–65 |

| IIIa | 50 | 45 |

| IIIb | 40 | 25 |

| IIIc | 30 | 20 |

| IV | 15 | 10 |

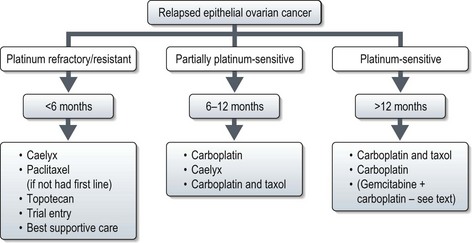

Relapse

Presentation of relapse

Relapse may be defined by conventional RECIST criteria (p. 44) or by the gynaecological cancer inter-group (GCIG) CA-125 criteria. CA-125 relapse for those who had elevated pre-treatment value which normalized after first line treatment (60% of all new patients) is defined as ≥2× upper limit of normal on two occasions not less than 1 week apart. Patients in whom CA-125 was elevated but never normalized (30% of all new patients): relapse is defined as a CA-125 value ≥2× nadir value on two occasions. The definition of relapse in patients with normal CA-125 prior to initial treatment (10% of all new patients) is similar to that of patients with elevated CA-125 which normalized after first line treatment.

Follow-up

Most (approximately 95%) recurrences will occur in the first 3 years and relapse after 5 years is rare. Follow-up is directed at detecting localized relapse which is potentially curable with surgery or radiotherapy, e.g. local vaginal vault relapse. Follow-up should include clinical examination, CA-125 (if elevated at presentation) and intermittent imaging if CA-125 was not informative or with symptoms. A typical follow-up would be 3-monthly for 2–3 years then 6-monthly up to 5 years. Patients with an informative CA-125 can become very focused on their blood result at each appointment so a clear plan of action with a raised CA-125 is recommended as there is no evidence that treatment with an asymptomatic elevated CA-125 improves outcome.

Endometrial cancer

Aetiology

Table 13.2 shows the risk factors for endometrial cancer. Less than 5% of endometrial cancers are hereditary, and most of these arise in women with hereditary non-polyposis coli (HNPCC) or Lynch syndrome II (p. 51).

Table 13.2 Risk factors for endometrial cancer

| Risk factor | Relative risk |

|---|---|

| Increased age | – |

| Unopposed oestrogen | 2–10 |

| Late menopause (after age 55) | 2 |

| Nulliparity | 2 |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 3 |

| Obesity | 2–4 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 |

| Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer | 22 to 50% lifetime risk |

| Tamoxifen | 2/1000 |

Pathogenesis and pathology

Histologic types of endometrial malignancies are as follows:

Diagnosis and staging

Initial investigations

Further investigations

Staging

The FIGO postoperative surgico-pathological staging system is given in Box 13.6.

Box 13.6

FIGO staging of endometrial cancer

Stage I* Tumour confined to the corpus uteri (includes endocervical gland involvement)

Stage II Tumour invades cervical stroma, but does not extend beyond the uterus

Prognostic factors

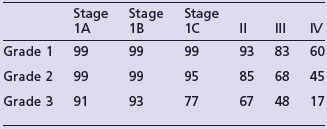

The most important prognostic factors are stage, age, depth of myometrial invasion >50%, grade 3, serous or clear cell histology and lymphovascular invasion (LVI). Table 13.3 shows the 5-year survival rate according to stage and grade.

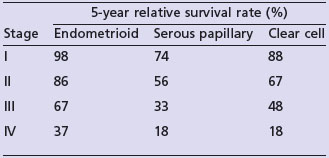

Endometrioid cancer presents more commonly with stage I and II (86%) than serous papillary (57%) or clear cell (70%). However, serous papillary and clear cell carcinomas have a poorer prognosis even after their stage at presentation is taken into account (see Table 13.4).

invasion of the myometrium, the risk is approximately 25%. With both these factors, there is a 34% risk of pelvic node involvement, and a 24% risk of aortic node involvement. North American practice is to perform routine bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection (BPLND) with or without para-aortic lymphadenectomy but there is no clear evidence that lymphadenectomy improves survival. The initial results of the ASTEC trial comparing pelvic lymphadenectomy with no lymphadenectomy in mostly stage I disease showed similar survival and progression free survival with both approach and hence the UK practice is to perform lymph node sampling of clinically suspicious nodes only. The rationale being patients with micrometastases will be identifiable as having a high risk of locoregional relapse and these patients can be stratified to receive radiotherapy. Some UK centres perform lymphadenectomy in stage I patients with a high risk of locoregional relapse, and omitting External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) to those with uninvolved nodes.

invasion of the myometrium, the risk is approximately 25%. With both these factors, there is a 34% risk of pelvic node involvement, and a 24% risk of aortic node involvement. North American practice is to perform routine bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection (BPLND) with or without para-aortic lymphadenectomy but there is no clear evidence that lymphadenectomy improves survival. The initial results of the ASTEC trial comparing pelvic lymphadenectomy with no lymphadenectomy in mostly stage I disease showed similar survival and progression free survival with both approach and hence the UK practice is to perform lymph node sampling of clinically suspicious nodes only. The rationale being patients with micrometastases will be identifiable as having a high risk of locoregional relapse and these patients can be stratified to receive radiotherapy. Some UK centres perform lymphadenectomy in stage I patients with a high risk of locoregional relapse, and omitting External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) to those with uninvolved nodes.