Cancer of the Female Urethra

Primary urethral carcinoma is a rare tumor, accounting for <1% of all malignancies. Although previous data suggested that urethral cancer was more common in women than in men, a recent Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) study reported that primary urethral cancer was more common in men.1 The ratio of female to male predominance was approximately 1:3. Because of its rarity and lack of prospective data, optimal management of female urethral cancer is based on retrospective data and depends on the clinical stage, tumor location, extent of nodal involvement, and the patient’s health status and preference.

FIGURE 73.1. Magnetic resonance T1-weighted sagittal image of the female pelvis.

ANATOMY

ANATOMY

The female urethra is approximately 3 to 4 cm long and 0.6 cm in resting diameter. It is embedded in the anterior vaginal wall behind the pubis symphysis, extending inferiorly and anteriorly from the urinary bladder through the urogenital diaphragm to the vestibule, where it forms the urethral meatus. Because of the proximity of the symphysis pubis, a small curve is formed with an anterior concavity. The lower distal half of the urethra is considered the anterior urethra, and the upper proximal half is considered the posterior urethra. Figure 73.1 illustrates the urethra and adjacent organs in the female pelvis.

The wall of the urethra consists of three layers. The muscular layer is continuous with that of the bladder. At the vesicular end of the urethra, this muscular wall forms the internal sphincter. The voluntary urethral sphincter is at the plane of the urogenital diaphragm. A thin layer of erectile tissue consisting of a plexus of veins and muscle fibers forms the middle layer of the wall. The inner layer is the mucous membrane, which is continuous with the bladder proximally and with the vulva distally. This membrane consists of transitional epithelium near the bladder but distally changes to nonkeratinizing stratified squamous epithelium and pseudostratified columnar epithelium. The distal urethra also contains small mucous recesses and periurethral or Skene’s glands, most of which are in the region of the meatus.

The lymphatic drainage of the distal urethra and urethral meatus parallels that of the vulva to the superficial and deep inguinal and external iliac lymph nodes. The primary drainage of the posterior or entire urethra is mainly to the obturator and internal and external iliac nodes.

FIGURE 73.2. Coronal (A) and sagittal (B) T2-weighted magnetic resonance images demonstrate a large diverticulum surrounding the urethra with a tumor mass arising within the confines of the diverticulum posteriorly that results in an impression at the vagina.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND ETIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND ETIOLOGY

The SEER database for 1973 to 2002 identified 1,615 cases of primary urethral carcinoma, of which 540 were women.1 The overall annual incidence was 1.5 per million for women (4.3 per million for men). Although previous observation suggested that this cancer is more common in white than in black women,2,3 the SEER data show that the incidence is higher for African Americans and increases steadily with age. Because carcinoma of the urethra is rare in women, only a few cases are seen annually at major cancer centers.4–7 Carcinoma of the female urethra makes up 0.02% of all cancers in women and accounts for approximately 0.1% of all gynecologic cancers.8,9 The average patient age at the time of diagnosis is 60 years, with most patients between 50 and 80 years of age.1,2,10–12

Although chronic infection and local irritation have been proposed, the etiology of female urethral cancer remains obscure. Unlike other transitional cell carcinomas of the urinary tract, there is no reported correlation of cigarette smoking with urethral carcinoma. Weiner and Walther13 analyzed archival surgical specimens of women with urethral carcinoma. Human papilloma virus (HPV) was detected in 10 of 17 patients with invasive disease. HPV type 16 was found in 8 patients. Eight women with squamous cell carcinoma and 2 with transitional cell carcinoma had HPV. Female urethral cancer may also be associated with urethral diverticula.14–16 Figure 73.2 illustrates a carcinoma arising within a urethral diverticulum. Patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder, especially the bladder neck, may have a higher risk of developing urethral cancer either synchronously or metachronously.17,18

NATURAL HISTORY

NATURAL HISTORY

Most urethral cancers are clinically aggressive and historically carry a poor prognosis. During the later stages, cancers of the middle or posterior urethra tend to extend upward into the urinary bladder, downward to invade the remainder of the urethra, and posteriorly into the vaginal mucosa. Lesions involving the anterior urethra account for approximately 30% of all cases.10,19

Regional lymph node involvement is uncommon in early tumors (stage 0) of the urethral meatus. Advanced tumors (stages II and III) of the urethra have been associated with a 35% to 50% incidence of inguinal or pelvic lymph node involvement.9,11,20–22 Bilateral nodal involvement occurs in approximately one-third of patients with positive nodes. Grabstald10 confirmed nodal involvement in 24 of 25 patients with clinically palpable nodes. In his series of patients with advanced disease, 26 underwent pelvic lymph node sampling and 13 (50%) had nodal involvement.

Distant metastases are found in approximately 10% of patients at presentation, and approximately 30% to 50% ultimately die of distant disease. The most common sites of metastasis are lung, liver, bone, and brain.10,23

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A majority of patients with urethral cancer present with some degree of irritative or obstructive urethral symptoms.24 Bleeding (hematuria) or spotting is the prevailing presenting sign in 50% to 60% of patients.2,25,26 Approximately 30% to 50% of patients experience pain or irritative symptoms, difficulty urinating, and frequent micturition. Urinary retention and overflow incontinence may occur in advanced cases. Less frequently cited signs and symptoms are a mass in the introitus (10% to 20% of patients), dyspareunia, perineal pain, and inguinal lymphadenopathy.21,23,27 Urethrovaginal and vesicovaginal fistulas may develop in advanced, neglected cases.

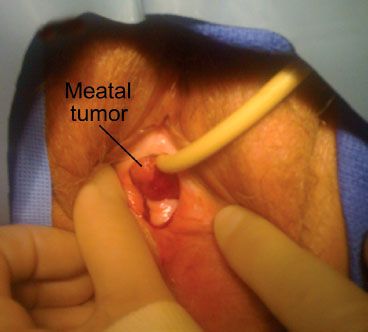

Small tumors involving the urethral meatus are often mistakenly diagnosed as urethral caruncle, a benign, inflammatory lesion, or a prolapse of the mucosa through the urethral orifice. As the lesion progresses, it enlarges and eventually ulcerates.23 Tumors may arise in a urethral diverticulum.16,28 Larger lesions of the distal urethra are readily identified on inspection (Fig. 73.3). Tumors occupying the proximal urethra may produce a fusiform enlargement that can be palpated during pelvic examination.

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

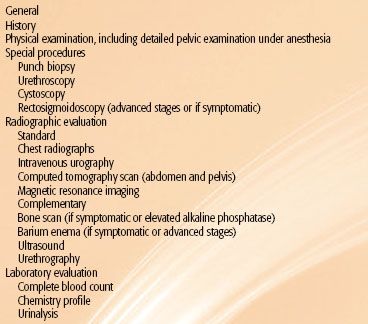

An outline for the diagnostic work-up for carcinoma of the female urethra is presented in Table 73.1. A routine history and general physical examination should be performed for all patients. A detailed pelvic examination under anesthesia is necessary to fully evaluate the clinical extent of the disease. This examination can be performed at the time of urethroscopy and cystoscopy. Urine cytologic analyses have a high false-negative rate.29 The definitive diagnosis is made by punch or incisional biopsy.

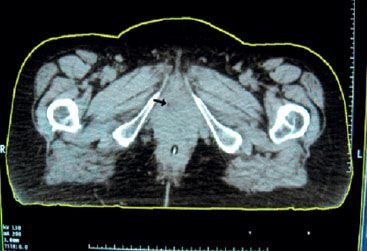

Routine radiographic evaluation should include chest radiographs, an intravenous urogram, and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis (Fig. 73.4).30,31 Barium enema can be cost-effective for patients with symptoms of advanced disease. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis helps delineate the tumor extent, especially when an endourethral coil is used (Fig. 73.2). It provides a discrete view of the muscular layers of the urethra.32,33 Additional complementary studies include interactive virtual urethrography and ultrasonography, which can help detect a urethral diverticulum without contrast agent filling.34 Multidetector CT voiding urethrography yields real-time urethral images during micturition.

Currently there are no studies to address the role of positron emission tomography (PET) with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) scan in urethral cancer. Perhaps some genitourinary tumors do not accumulate sufficient FDG, which may not be a useful tracer for the detection of primary genitourinary tumors because of its physiologic excretion in the urine.35 However, PET scans may potentially be useful for identifying nodal and distant sites of disease, especially in patients with equivocal findings on conventional imaging.36,37

FIGURE 73.3. A meatal carcinoma of the urethra in a 68-year-old white woman presenting with hematuria.

FIGURE 73.4. Transaxial computed tomography image of a patient with urethral cancer illustrating the periurethral and anterior vaginal wall expansion and deviation of the urethra (arrow).

TABLE 73.1 DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP FOR CARCINOMA OF THE FEMALE URETHRA

TABLE 73.2 PROPOSED CLINICAL STAGING SYSTEM FOR CARCINOMA OF THE FEMALE URETHRA

STAGING SYSTEMS

STAGING SYSTEMS

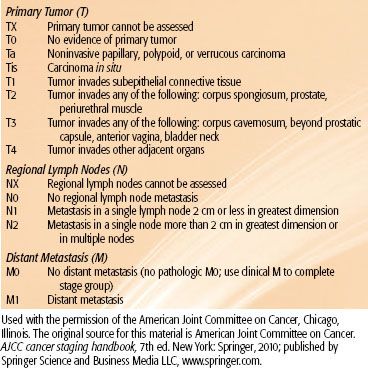

Clinical staging is based on findings on physical examination, chest x-ray, and CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis. Many attempts have been made to formulate a staging system for carcinoma of the urethra. Urethral tumors can be classified in two groups: those involving the distal half of the urethra and those located in the proximal or entire urethra. Most authors have found that this classification correctly depicts the feasibility of treatment and the prognosis. A staging system based on location has been proposed by Prempree et al.38 (Table 73.2). The current TNM staging system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer is shown in Table 73.3.39

TABLE 73.3 AMERICAN JOINT COMMITTEE ON CANCER STAGING OF CARCINOMA OF THE URETHRA (MALE OR FEMALE)

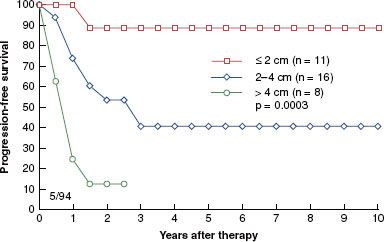

FIGURE 73.5. Progression-free survival correlated with tumor size. (From Grigsby PW, Herr HW. Urethral tumors. In: Vogelzang J, Scardino PT, Shipley WU, et al., eds. Comprehensive textbook of genitourinary oncology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:1117–1123.)

FIGURE 73.6. Progression-free survival correlated with tumor location. (From Grigsby PW, Herr HW. Urethral tumors. In: Vogelzang J, Scardino PT, Shipley WU, et al., eds. Comprehensive textbook of genitourinary oncology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:1117–1123.)

PATHOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION

PATHOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION

Because the urethra is lined by transitional cells proximally and stratified squamous cells distally, transitional cell carcinoma occurs typically in the proximal urethra, whereas squamous cell carcinoma occurs frequently in the distal urethra. The SEER data report that the most common histologic type is transitional cell carcinoma, followed by squamous cell and adenocarcinoma.1 However, most published series suggest that squamous cell carcinoma is the most common histologic type in cancer of the female urethra, representing >50% of all cases, whereas transitional cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma represent approximately 15% to 20% and 10% to 15%, respectively.15,40,41 The remainder of the histologic types include adenoid cystic carcinoma, melanoma, clear-cell adenocarcinoma, anaplastic tumors, Kaposi’s sarcoma, lymphomas, and metastatic lesions.6,28,31,42–49

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

Conventional prognostic factors, such as grade and histology, have not been consistently predictive for recurrence or survival for female urethral cancer. In the literature, some of the most important factors in determining prognosis and survival are stage, depth of invasion, tumor size, and anatomic location.2,15,21,50–52 Dalbagni et al.2 showed that primary stage was one of the major independent predictors of survival in 72 female patients, with 5-year survival of 83% for low-stage tumors and 33% for high-stage tumors.

Lesions located in the meatus or distal urethra tend to be superficial, with a better prognosis; lesions in the posterior urethra are often deeply invasive and tend to have a worse prognosis.9 Most investigators found that patients with advanced-stage disease do poorly, often irrespective of their treatment.2,24,51,53

Grigsby and Corn25,54 demonstrated a worsening prognosis with increased tumor size. The 5-year progression-free survival was 81% for patients with lesions <2 cm, compared with 37% for those with lesions 2 to 4 cm and 7% for patients with lesions >4 cm (p = .0001). For lesions confined to the proximal urethra, local control was observed in all four patients. However, patients with tumors involving the distal urethra had a 5-year progression-free survival rate of 69%, and there was a 12% survival rate for those with involvement of the entire free urethra (p = .0001). Patients with meatal tumors, if diagnosed early and treated appropriately, can achieve an 80% to 90% survival rate (Figs. 73.5 and 73.6).25 Bladder neck involvement, parametrial extension, and inguinal lymph node involvement have been identified as poor prognostic factors.

The histology of the primary lesion appears to be less important as a prognostic factor in determining response to therapy and survival. Patients with adenocarcinoma have been reported to have a good prognosis, but most studies have shown no difference in survival among patients with adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and transitional cell carcinoma.10,14,38,50 Grigsby25 found a worse prognosis in patients with adenocarcinoma. Primary melanoma of the urethra, although rare, has a very poor prognosis.43,44

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

Although various therapeutic approaches have been advocated in the management of carcinoma of the female urethra, there are no established therapeutic guidelines. The variety of treatments reflects the dimensions and locations of disease and the approaches of the treating physicians.55 In general, surgical resection is a primary mode of treatment.56 Radical urethral resection with urinary diversion and pelvic lymphadenectomy are commonly performed for lesions not involving the bladder neck. However, early-stage lesions of limited extent may be amenable to organ-sparing radiation therapy or conservative surgical management with or without adjuvant radiation therapy to minimize the morbidity associated with surgical intervention. Surgical approaches include neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser coagulation,57 Mohs’ micrographic surgery, and partial or total urethrectomy.41 Radiation therapy may include external-beam radiation, interstitial brachytherapy, or a combination of these treatments.58 For patients who are medically nonsurgical candidates because of potential risks of anesthesia, outpatient high–dose-rate intracavitary and intraluminal brachytherapy may be an option.59

For patients with locally invasive urethral carcinoma, anterior exenteration may be required. Although most available data are insufficient, in patients with more advanced disease, some authors have advocated adjuvant radiation therapy and/or combined irradiation and chemotherapy, including 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, vinblastine, epirubicin, carboplatin, bleomycin, methotrexate, or mitomycin-C after surgical extirpation.56,60–64

Anterior (Distal) Urethral Cancer

For stage 0 and I (Ta, Tis, or small T1) lesions, open excision, electroexcision, fulguration, and laser (Nd:YAG or CO2) coagulation are possible for tumors at the meatus or with in situ involvement of the distal urethra (stage 0). For larger and more invasive lesions (stage T1 and T2), surgical resection of the distal one-third of the urethra is often adequate. Alternatively, interstitial irradiation or a combination of interstitial and external-beam irradiation can be considered. For T3-T4 or recurrent anterior urethral lesions previously treated by local excision or radiation therapy, anterior exenteration and urinary diversion may be curative. Adjuvant radiation therapy may be required, depending on surgical findings.

If a limited number of inguinal nodes are involved, ipsilateral node dissection or irradiation is indicated because cure is still achievable. If no inguinal adenopathy exists, node dissection is not recommended, but prophylactic groin irradiation is recommended for patients with invasive lesions.6,50

Posterior (Proximal) Urethral Cancer

Cancers of the posterior or entire urethra are usually associated with invasion of the bladder, a high incidence of inguinal and pelvic lymph node metastases, and a worse prognosis. For lesions <2 cm, radical resection, definitive radiation therapy, or combined treatment may provide adequate control.54 However, for larger lesions or locally advanced disease, the best results have been achieved with preoperative irradiation, exenterative surgery, and urinary diversion. Pelvic lymphadenectomy is performed, and inguinal node dissection may be indicated if the inguinal nodes are involved. In selected patients, it is possible to remove part of the pubic symphysis and the inferior pubic rami to maximize the surgical margin. A transpubic approach has been advocated by Golimbu et al.65 Perineal closure and vaginal reconstruction can be accomplished with the use of myocutaneous flaps. Hedden et al.66 advocated the use of bladder-sparing surgery with or without irradiation.

Recurrent Urethral Cancer

In most cases, locally recurrent urethral cancer after surgery alone should be considered for combination radiation therapy and wider surgical resection. Locally recurrent urethral cancer after radiation therapy should be treated by surgical excision. For patients who are not surgical candidates, local reirradiation (i.e., hyperfractionated intensity-modulated radiation therapy or brachytherapy) may be considered if radiation tolerance has not been exceeded. Patients with metastatic urethral cancer should be considered for investigational chemotherapy protocols. Palliative radiation therapy may provide good symptomatic relief.

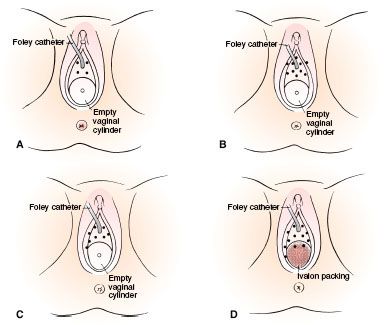

FIGURE 73.7. Diagrams of implants. A: Tumor limited to the urethra. B: Tumor extending to the periurethral tissues or originating in the periurethral glands. C: Tumor extending into the vagina or labia minora. D: Tumor involving the suburethral area. (From Delclos L. Carcinoma of the female urethra. In: Johnson DE, Boileau MA, eds. Genitourinary tumors. New York: Grune & Stratton, 1982:275–286, with permission; copyright Elsevier, 1892.)