© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015

Jean-Pierre Droz, Bernard Carme, Pierre Couppié, Mathieu Nacher and Catherine Thiéblemont (eds.)Tropical Hemato-Oncology10.1007/978-3-319-18257-5_36Pancreatic Cancer

(1)

Department of Medical Oncology, Centre Léon-Bérard, University of Lyon, 28 rue Laënnec, 69008 Lyon, France

(2)

Medical Oncology Outpatients Clinic, Centre Hospitalier de Cayenne, Cayenne, Guyane Française

1 Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the fourth most frequent cause of tumor-related death in the Western world [24, 25]. Few data are published concerning PDAC frequency in tropical countries, but it may be less frequent than in more developed countries [1, 10, 15]. However, its incidence is increasing worldwide, and PDAC will become by 2020 the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality [16]. Median survival is 5–8 months and median 5-year survival is less than 5 % [23]. Majority of the patients are diagnosed with metastases and are candidates for palliative treatment.

2 Risk Factors

PDAC is usually sporadic but may be familial, needing attentive care to familial history.

Sporadic PDAC development is the result of a combination of different causes including somatic genomic, genetic, and epigenetic alterations and environmental factors, especially cigarette smoking and alcohol. Long-standing type 2 diabetes mellitus is also associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer [13]. Tropical calcific pancreatitis (TCP) has been described as a form of chronic nonalcoholic pancreatitis and is associated with a 4 % lifetime risk of developing cancer [19]. The typical clinical phenotype of TCP includes an onset at less than 30 years of age, a body mass index (BMI) less than 18 kg/m2, absence of any other cause of pancreatitis, and presence of diabetes [5].

Hereditary basis of PDAC is traditionally found in 5–10 % of patients [20]. Subsets of familial pancreatic cancer involve germ line cationic trypsinogen or PRSS1 mutations (hereditary pancreatitis), BRCA mutations (usually in association with hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndrome), CDKN2 mutations (familial atypical mole and multiple melanoma), or DNA repair gene mutations (e.g., ATM and PALB2, apart from those in BRCA) [29].

3 Diagnosis

Histological diagnosis should be obtained when nonsurgical treatment is considered, because 10 % of malignant tumors of the pancreas aren’t exocrine and all pancreatic tumors are not malignant. If the tumor is resectable, a biopsy is not recommended/mandatory in order to avoid gesture’s morbidity and theoretical risk of tumor seeding along the needle tract [6]. In case of diagnostic doubt (nodule of pancreatitis or a pseudotumor pancreatitis) and unresectable or metastatic tumor, a fine-needle cytology or tumor biopsy needs to be achieved. When endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is available, fine-needle aspiration may be EUS-guided (EUS-FNA). EUS may be also useful to detect vascular invasion and to treat pain through celiac plexus block and obstructive jaundice through biliary drainage [11]. If EUS is not available, ascites or hepatic metastases may be sampled under radiological guidance (ultrasound or CT scan).

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is the primary and easily available modality for both diagnosing and staging [2]. It is typically a multiphase thin-section imaging technique showing the primary tumor at the earlier phase, while the latter phase best demonstrates tumor involvement of venous structures and liver metastases [4]. Pancreatic magnetic resonance (MR) imaging may be useful but is not mandatory [21]. Likewise, 18FDG PET/CT also offers no benefit over CT scan in diagnosing pancreatic cancer [22].

The staging system for pancreatic exocrine cancer is defined by the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)/TNM classification [9].

4 Treatment of Resectable Tumors

Resectable tumors include AJCC stages I and II. It concerns only 10–20 % of the patients. The surgical procedure for the pancreatic head’s tumors is a pancreaticoduodenectomy or Whipple procedure involving the removal of the distal half of the stomach, gallbladder, distal portion of the common bile duct, as well as the head of the pancreas, duodenum, proximal jejunum, and lymph nodes. Three anastomoses are required for reconstruction, namely, pancreaticojejunostomy, choledochojejunostomy, and gastrojejunostomy. As morbidity and mortality can be high following surgery, patients need to be addressed in high-volume centers [30]. Recurrences after initial surgery are frequent, and 5-year survival after surgical resection of PDAC is as poor as 18–27 % and correlates with resection margin status (R0 vs. R1) and lymph node metastases [14]. A 6-month adjuvant therapy with 5-FU or gemcitabine-based chemotherapy is recommended for all patients after pancreatic surgery, independently of the T and N stages [17, 18]. The median overall survival for patients with resected pancreatic cancer treated with adjuvant chemotherapy is approximately 2 years.

5 Treatment of Locally Advanced Unresectable Tumors

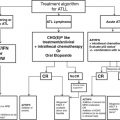

Locally advanced pancreatic cancers (stage III) are divided into borderline resectable or locally advanced unresectable tumors. They are separated according to the relationship of the tumor to the adjacent major vascular structures (superior mesenteric artery (SMA), celiac axis, and superior mesenteric and portal veins (SMV–PV)). Tumors without vessel involvement or with only focal involvement of the SMV–PV confluence are considered to be resectable, while patients whose cancers involve arteries or have more extensive involvement of the SMV–PV confluence are classified as having clinical stage III tumors. Their median survival in most historical studies ranges from 8 to 12 months. In this setting, treatment options include mostly chemotherapy (CT), chemoradiation (CRT), and surgery but strong evidences for therapeutic sequences are lacking. Controversies mainly exist about the place of radiation therapy, because the definition of locally advanced pancreatic cancers varies in published series, borderline resectable and unresectable tumors are both included in the same studies, and metastatic progression during or immediately after radiation is usual. Recently, the LAP 07 trial showed no benefit in survival for CRT after 4 months of gemcitabine-based induction CT over CT alone in locally advanced unresectable tumors. Despite these results, chemoradiation is not abandoned and remains investigated after more aggressive neoadjuvant CT (like FOLFIRINOX or nab-paclitaxel–gemcitabine). At least, due to the high rates of metastatic progression, it is recommended to use first induction CT which may subselect the proportion of patients who may benefit from subsequent CRT. In borderline resectable pancreatic cancer, the role of CRT remains less controversial and will be answered in future prospective phase III trials.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree