Age (years)

White female (years)

Black female (years)

Hispanic female (years)

60

24.5

23

26.3

65

20.3

19.3

22.0

70

16.4

15.8

18.0

75

12.8

9.6

14.0

80

9.6

7.1

10.7

85

6.9

5.2

7.7

90

4.8

3.8

5.4

Treatment Pattern

Despite breast cancer being a disease of the elderly, this age group has historically been excluded from clinical trials [5]. Given this lack of data, physicians are left to decide their treatment plan based on extrapolated data and experience. This has led to deviations from the standard of care in treating elderly women with breast cancer. When standard of care was applied, such as mastectomy and axillary dissection, these women were thought to be overtreated. However, those patients who underwent breast-conserving surgery and had omission of axillary dissection and/or radiation therapy might be considered to be under treated. Older women with breast cancer are less likely to receive standard treatments, such as axillary lymph node dissection or radiation therapy, after breast-conserving surgery compared to younger patients [6]. Possible explanations of under treatment include shorter life expectancy, increasing medical comorbidities, and less aggressive biologic behavior of breast cancer [7–10].

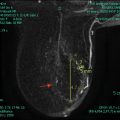

Screening

The risk of developing breast cancer increases with age, making screening older women valuable. A quarter of breast cancer deaths each year are attributed to breast cancer diagnosed after the age of 74 [11]. Screening methods include mammograms, clinical breast examination, and breast self-awareness. Sensitivity and specificity of mammography increase as patient gets older due to decrease in glandular breast tissues and replacement with fatty tissue. This decreases unnecessary biopsies and intuitively provides a substantial opportunity to reduce breast cancer death in older populations. Unfortunately, none of the randomized prospective trials of screening mammography included women over the age of 75 making continued use of screening mammography clinical decision in this population difficult [12]. There have been a few observational studies demonstrating a reduction in breast cancer mortality associated with mammographic screening in women 75 years and older; however, the benefits were limited to those without severe comorbidities, and no benefit was observed in women with severe comorbidities [13, 14]. These results must be interpreted with caution given the limitations of study design. It has been suggested that older women with comorbidities, such as those with Charleston Comorbidity Index of two or more, may not benefit from screening mammography due to competing causes of mortality [15].

Another issue with older women and breast screening is determining when to stop screening. The United States Preventive Service Task Force recommends stopping at age 75, whereas the American Cancer Society recommends continuing as long as a patient is healthy and has a life expectancy of more than 10 years. The American College of Radiology also recommends continued screening if the patient is healthy and willing to undergo additional testing (including biopsy). Variations in screening recommendations are shown in Table 13.2. Overscreening in elderly women is a health-care concern as well, with recent studies demonstrating that many elderly women with multiple comorbidities and advanced cancer are still undergoing screening mammography [16, 17]. It is important to evaluate individual patients to determine if mammographic screening is of benefit as patients with multiple comorbidities will not experience reduction in breast cancer mortality from screening.

Table 13.2

Variations in current mammography screening guidelines for average-risk women

Screening frequency | Age to start screening | Age to stop screening | |

|---|---|---|---|

US Preventative Services Task Force [39] | Biennial | 50 | 75 |

American Cancer Society [40] | Annual | 45–54 | Continue as long as healthy and life expectancy ≥10 years |

Biennial | ≥55 | ||

American College of Radiology [41] | Annual | 40 | Stop when life expectancy is <5–7 based on comorbidities and when abnormal result would not be acted on because of comorbidity |

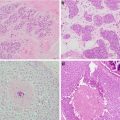

Tumor Biology

Breast cancer in the elderly patient is less aggressive. Older women tend to have more favorable tumors at diagnosis that are likely small, have less nodal involvement, express both estrogen and progesterone receptors, are more low grade, and are HER-2 negative [32]. Molecular genetics shows that more favorable luminal A and luminal B subtypes are found in older women. However, older women can present with triple negative or HER-2 amplified cancers. Treatment needs to be based on these phenotypes as well as tumor size and nodal involvement.

Treatment

Surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment in elderly women with breast cancer. Treatment should be based on staging of the cancer, and patients should receive standard of care if possible. Surgery and anesthesia carry some risks independent of age, however, the main factor influencing morbidity and mortality from breast surgery is comorbidity rather than age alone [18]. A recent retrospective study of SEER analysis evaluated outcomes of 1784 breast cancer patients over the age of 70 undergoing mastectomy and lumpectomy [19]. Of these, 596 (33%) underwent mastectomy, 918 (51%) underwent lumpectomy with radiation, and 270 (15.4%) underwent lumpectomy alone. The type of surgery was not an independent factor in determining overall survival. The SEER study showed worse breast cancer-specific survival that was associated with an inability to perform more than two activities of daily living, two or more comorbidities, larger tumor size, and positive lymph nodes. On multivariate analysis, larger tumor size and positive lymph nodes were identified as independent determinants for worse survival [19]. This suggests that even in elderly patients, nodal staging remains an important part of breast cancer treatment. In contrast, another study of 140 women over the age of 70 who did not undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy demonstrated a low axillary recurrence and low mortality for patients with clinical T1–2 N0 breast cancer [20].

Surgical staging of the axilla may be omitted in elderly patients with clinically node-negative disease as information from axillary surgery may not alter treatment decisions in many cases. This is especially true in the frail patient who is not a candidate to receive chemotherapy regardless of their nodal status. In elderly women with clinically node-negative, hormone receptor-positive disease, adjuvant therapy will likely be limited to endocrine therapy . The rate of axillary recurrence following lumpectomy and endocrine therapy in patients without radiation therapy or axillary surgery was 1% at 5 years as demonstrated in CALGB 9343 [20, 21]. This is a small enough risk that axillary staging may be omitted in selected patients.

Radiation Therapy

There have been two recent prospective randomized trials to determine whether there is a benefit of adjuvant radiation therapy after breast-conserving surgery in elderly patients with early breast cancer. CALGB-9343 randomized 636 stage I, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patient’s age ≥70 to lumpectomy with tamoxifen only or lumpectomy with tamoxifen and radiation therapy [21]. This study showed there were no significant differences in time to distant metastasis, breast cancer-specific survival, or overall survival between the two groups. Ten-year overall survival was 67% (95% CI, 62–72%) and 66% (95% CI, 61–71%) in the tamoxifen and radiation therapy and tamoxifen only groups, respectively [20].The PRIME II study was another study evaluating the effect of omitting whole-breast irradiation on local control in women aged 65 years or older undergoing lumpectomy and endocrine treatment for early stage breast cancer. After a median follow-up of 5 years, local recurrence was 1.3% (95% CI 0·2–2·3; n = 5) in the whole-breast irradiation group and 4.1% (2∙4–5∙7; n = 26) in the group without radiation therapy. Whole-breast irradiation after breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant endocrine therapy resulted in a small, but statistical significant reduction in local recurrence; however, there was no difference in 5-year overall survival between the two groups 93.9% (95% CI 91.8–96.0) [22]. Especially in in early stage estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer in the elderly, radiation therapy may be omitted without significant consequence. Despite these data, the omission of radiation therapy in selected older population has not been widely applied [23, 24].

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is underutilized in older women, and there are few prospective randomized clinical trials in this population. For the older patient, their comorbidities, functional status, social support, and life expectancy must all be taken into account before selecting patients for treatment [32]. Standard-of-care treatments should be used in those healthy older adults whose life expectancy is equal to or greater than 10 years.

Adjuvant chemotherapy is generally recommended for women with ER-negative or Her-2/neu amplified tumors that are larger than 1 cm or any subtype in which lymph node involvement is found. A retrospective review of four randomized studies has shown that the administration of intensive chemotherapy regimens in older patients results in a reduction in breast cancer recurrence and morality, regardless of age [25]. Furthermore, a consensus panel as part of the NCCN’s published recommendations in 2008 suggested that the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in older patients should be guided by a well-balanced consideration of benefit-fit risk ratio. No specific chemotherapy regimen is recommended for older patients, but caution should be given for anthrocyclines and consideration for hepatic and renal function [32]. ER-negative breast cancer can be particularly aggressive and tend to recur in the first 5 years. For older women with ER-negative breast cancer, several retrospective analyses also support the use of adjuvant chemotherapy. Two analyses using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database have demonstrated that adjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of node-positive, ER-negative breast cancer is associated with a reduction in mortality [26, 27].

The use of trastuzumab in Her-2-positive breast cancer in the elderly also needs special attention. Trastuzumab is associated with improvement in disease-free and overall survival; however, the scope of the benefit in older patients is hard to determine given that few older women enrolled in the randomized trials [28, 29]. Older age is a recognized risk factor for trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity [30]. Significant associations with CHF and trastuzumab exposure include use of hypertensive medications, lower baseline left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF ), and lower LVEF following treatment with doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide. In conclusion, consensus opinion issued by the NCCN is that the small numbers of cardiac-related deaths and added valued and therapeutic index of adjuvant trastuzumab should not preclude trastuzumab’s use in the treatment of healthy elderly women [31, 32].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree