Breast Cancer: Stage Tis

Noninvasive carcinoma of the breast (stage Tis) includes Paget’s disease of the nipple and two histopathologic entities that are distinct in both their clinical presentation and biologic potential: lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). As a result of the increase in the use of mammography, these three histopathologic entities comprise a larger percentage of all breast cancer cases seen today. There remains considerable controversy regarding the optimal treatment approach and, as a consequence, treatment recommendations range from observation to breast conservation therapy to mastectomy. It is, therefore, important to understand the distinguishing pathologic appearances, biologic characteristics, and natural history of these three noninvasive breast disease entities to appropriately formulate coherent treatment recommendations.

LOBULAR CARCINOMA IN SITU

LOBULAR CARCINOMA IN SITU

LCIS is characterized by multicentric breast involvement and consists of loose, discohesive epithelial cells that are large in size, variable in shape, and contain a normal cytoplasm to nucleus ratio.1 The extent of involvement of the lobular lumen ranges from simple filling to moderate to severe distention with extension into the adjacent extralobular ducts.2 As such, the lines of histologic delineation can become blurred between atypical ductal hyperplasia, LCIS, and, when ductal extension is seen, DCIS. This overlap of histologic morphology may complicate the interpretation of studies from different institutions.1–4

LCIS has been reported to present with a multicentric distribution in up to 90% of mastectomy specimens, with bilateral involvement in 35% to 59%.5,6–7 LCIS cells are commonly estrogen-receptor positive, although overexpression of c-erbB-2 and p53 are uncommon.4,8,9–10 The loss of E-cadherin is often observed,8,11,12 and the absence of this adhesion molecule may explain the growth pattern seen with LCIS.

LCIS represents <15% of all noninvasive breast cancer.13–15 The majority of women are premenopausal at diagnosis, with an average age of 45 years.1,3,16 Risk factors for the development of LCIS correspond to those identified for invasive carcinoma.17 Because the male breast lacks lobular elements, this entity has not been described in men.3 As there are no clinical or mammographic indicators that are characteristic of LCIS, it is often detected as an incidental biopsy finding.1,4 In a minority of cases, LCIS can be detected with mammographic calcifications; however, more commonly, calcifications are in adjacent tissue and are not histologically associated with LCIS.18–20 In excisional biopsy specimens, DCIS or invasive carcinoma are frequently identified even when LCIS is the sole histologic entity seen on core biopsy.21–23

LCIS is considered a marker of increased risk for the subsequent development of invasive (usually ductal) carcinoma3,13,14,16 that may be greatest for high-grade or more extensive lesions.1,24 This risk appears to be nearly equal for both breasts.25

The question as to whether LCIS can serve as a direct precursor lesion to the subsequent development of invasive lobular carcinoma is unresolved. Some studies have suggested a clonal link of synchronously detected LCIS and invasive lobular carcinoma,26 whereas others have not.27 In an analysis of 182 patients with LCIS who were inadvertently enrolled on the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-17 trial for DCIS and treated with lumpectomy only, there was a 14.4% in-breast tumor recurrence (IBTR) rate and a 7.8% contralateral breast tumor recurrence rate after a median follow-up of 12 years.28 Nine IBTRs (5% of the total cohort) were invasive carcinoma, and 17 (9% of the total cohort) were DCIS. Although the frequency of contralateral breast tumor recurrence rate was less than that of IBTR, the frequency of invasive contralateral breast tumor recurrence rate (5.6% of total cohort) was similar to invasive IBTR (5% of total cohort). Of note, all of the IBTR were documented to be at the site of the index lesion except for one, characterized as pure LCIS, that was found at a remote site.

The evidence associating LCIS with the subsequent development of invasive disease raises the question as to whether magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) would be a useful screening tool. Limited data exists to formulate a firm recommendation. In 2007, the American Cancer Society stated there was insufficient data; however, in 2009, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network published guidelines reflecting a panel consensus opinion that annual breast MRI should be considered in patients with LCIS. Since 2007, three studies have been published evaluating the role of MRI in patients with LCIS.29–30,31 Each document revealed a small but defined 3.8% to 4.5% breast cancer detection rate supporting consideration for an annual MRI in this subset of patients.

Management for LCIS depends on whether it is associated with another malignancy (DCIS or invasive carcinoma) or if LCIS is the sole histologic diagnosis. Approximately 10% of early-stage breast cancers have an associated component of LCIS.32–34 The effect that LCIS has on the outcome of conservative management of early-stage breast cancer has only recently been evaluated. Limited studies suggest that the presence of LCIS should influence treatment approach35; however, the most widely accepted treatment approach is to manage the breast according to the dominant malignant histology (DCIS or invasive carcinoma) and disregard the LCIS. In such circumstances, it is not necessary to pursue additional surgery to obtain clear margins for LCIS.27,32,33,36,37

If LCIS is the sole histologic diagnosis, treatment recommendations range from conservative to radical. When first described as an entity, the significance of LCIS was unknown and mastectomy was often performed.38 The high frequency of contralateral breast involvement was subsequently used to justify contralateral biopsy and even bilateral mastectomy.16,38 Observational studies after wide local excision alone have led to a better understanding of the natural history of this condition, and a more conservative approach is now commonly practiced.3,13,14 In patients with LCIS as the sole histologic diagnosis, the most widely accepted clinical practice is close observation with regular physical examination and mammographic surveillance.3,13–15,28 There is no role for radiotherapy in the management of LCIS. The fact that LCIS commonly involves both breasts makes treatment with unilateral mastectomy both inadequate and illogical. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy is likely excessive in all but those patients believed to be at highest risk: young age, diffuse high-grade lesion, and significant family history. A less radical prophylactic approach in high-risk patients is to consider the use of tamoxifen. Tamoxifen has demonstrated efficacy in the prevention of invasive carcinoma and, in the context of LCIS, has been shown to reduce risk by 56%.39,40

PAGET’S DISEASE

PAGET’S DISEASE

The clinical presentation of crusting and eczematous changes of the nipple–areola complex were first described in 1856. However, it was not until 1874 that the association with an underlying breast cancer was reported by Sir James Paget.41 Paget’s disease of the nipple is characterized by the presence of Paget’s cells that are located throughout the epidermis.42 Paget’s cells are large and have hyperchromatic, round to oval nuclei with abundant amphophilic to clear cytoplasm. Mitoses are commonly seen, and the cells can be found in clusters or individually in the basal layers. The fact that Paget’s disease is associated with an underlying malignancy in >95% of cases has generated discussion regarding the origin of these malignant cells. The epidermotropic theory appears to be the prevailing opinion, with the belief that the disease originates from the underlying in situ or invasive disease. This is supported by histologic evidence of intraepithelial extension, immunohistochemical studies, and evidence suggesting that the epidermal keratinocytes release a motility factor, heregulin-α, that results in the chemotaxis of Paget’s cells that migrate to the overlying nipple epidermis.43,44

Paget’s disease is a rare entity representing <5% of all breast cancer cases45,46 and is typically diagnosed in the fifth or sixth decade of life. Synchronous bilateral and male Paget’s disease have been reported.43,47,48

Patients with Paget’s disease describe itching and burning of the nipple and areola. There is a slow progression toward a crusting eczematoid appearance that can extend to the periareolar skin. If neglected, bleeding, pain, and ulceration can occur.46,49 Alternatively, Paget’s disease can be asymptomatic and present as a pathologic finding after incidental surgical removal of the nipple–areolar complex.50 The differential diagnosis includes superficial spreading melanoma, pagetoid squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and clear cells of Toker.42,51 A palpable mass is detected in approximately 50% of patients at diagnosis; in >90% of cases, this will be an invasive carcinoma. In contrast, if no palpable mass is detected, 66% to 86% will have an underlying DCIS. These associated malignancies are usually located centrally, although they can occur elsewhere in the breast.43,46,52 Mammographic findings are frequent in the presence of a palpable mass; however, normal mammograms are reported in as many as 50% of cases.46,53

At presentation, clinical evaluation includes bilateral breast examination, mammography, and biopsy to confirm the diagnosis of Paget’s disease and to fully evaluate the extent of the associated malignancy. The prognosis does not depend on the diagnosis of Paget’s disease but rather on the associated malignancy. Therefore, local treatment, as well as systemic and regional nodal disease risk management, should be based on the associated disease.

Management of Paget’s disease continues to evolve. Mastectomy was employed in the past, although this has been increasingly supplanted by breast-conserving treatment.54–57 The infrequent occurrence of this disease entity, the range of disease presentations (nipple involvement with or without an underlying mass and association with invasive vs. noninvasive disease), and the variable extent of surgical resection has made the evaluation of treatment options difficult. Small series have described results with various forms of breast-conserving treatment, including wide local surgical resection alone, radiotherapy alone, and wide excision followed by whole-breast radiotherapy. Conservative surgery alone for Paget’s disease appears to be inadequate, with reported local recurrence rates of 25% to 40%.5,58,59,60,61,62 The use of radiotherapy alone has been reported as achieving an 85% local control rate in a small series of patients with Paget’s disease of the nipple who presented without an associated palpable mass.63 However, this approach has not been widely adopted because of the undefined histologic type and extent of the underlying disease leading to uncertainty in field design and total radiation dose.

The combination of limited surgical resection and postoperative radiotherapy appears to be the most practical breast-conserving approach. Two studies have evaluated the combined use of surgery and radiotherapy in Paget’s disease of the nipple. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Study 10873 was a multi-institutional registry trial that reported a 5-year local recurrence rate of 5.2%.64 In this study, a complete excision with tumor-free margins of the nipple–areolar complex and underlying breast tissue was followed by whole-breast radiotherapy. The median follow-up was 6.4 years, and the majority of these patients were found to have an underlying DCIS without a palpable mass. A separate study consisted of a seven-institution collaborative review of 36 patients with Paget’s disease without a palpable mass or mammographic density.65,66 Patient follow-up was a median of 9.4 years. The extent of surgical resection varied as patients underwent complete (69%) or partial (25%) excision of the nipple–areolar complex and underlying breast tissue, with 6% reported as biopsy only. The final margin status was documented as negative in 56%, positive in 6%, and unknown in 39%. All received whole-breast irradiation, and most received an additional boost dose to the tumor bed. The actuarial rate of local failure as the only site of first recurrence was 9% at 5 years and 13% at both 10 and 15 years. Two additional patients recurred in the treated breast simultaneously with regional and distant metastasis at 69 and 122 months. Despite the differences in clinical, pathologic, and treatment factors, statistical evaluation did not identify any factors that significantly predicted for risk of local recurrence.

Current data suggest that a combined-modality approach that conserves the breast is an appropriate alternative to mastectomy in properly selected patients with underlying noninvasive or invasive carcinoma of limited extent. As with any breast-conserving approach, patients with multicentric disease extension should be excluded. Surgical resection should include the nipple–areolar complex with microscopically clear margins surrounding both the Paget’s disease and the associated malignancy. Whole-breast radiotherapy is delivered with standard techniques. Management of regional nodes and the risk of systemic disease are dictated by the associated malignancy.

DUCTAL CARCINOMA IN SITU

DUCTAL CARCINOMA IN SITU

Clinical Presentation and Epidemiology

DCIS is a neoplastic process that is confined to the ductal system of the breast and lacks histologic evidence of invasion. These cells neither disrupt the basement membrane nor involve the surrounding breast stroma. This entity lacks the ability to metastasize and is confined to the breast.67–70 Axillary node involvement is rare (0% to 5%) and most likely is associated with an undetected focus of invasive carcinoma.71 Risk factors for the development of DCIS are the same as those identified for invasive carcinoma,17 including family history, reproductive events such as delayed age of first live birth and nulliparity, history of benign breast biopsy, and dietary factors such as alcohol consumption. Before the use of screening mammography, DCIS typically presented as a palpable mass or nipple discharge. An invasive component commonly was found, and pure DCIS rarely was encountered. The widespread use of mammography now routinely detects DCIS <1 cm in diameter and results in breast cancer–free survival rates that approach 100%.71

With the increased use of mammography and as pathologists began to recognize DCIS as a pathologic entity, the incidence of DCIS has markedly increased.72–74 The incidence of DCIS in the United States rose from 4,800 cases in 1983 to >50,000 cases in 2004, representing a 10-fold increase in only 20 years.75 Of the nearly 290,000 new breast cancers that occur annually, approximately 58,000 are anticipated to be noninvasive, of which 85% will be DCIS.76 Of these, 90% are expected to be nonpalpable.44 Studies have shown that the rate of screen-detected DCIS increases with age despite that it accounts for a progressively smaller proportion of the total breast cancers detected.77 The rate of DCIS detection has been reported to increase from 0.56 per 1,000 mammograms among women aged 40 to 49 years to 1.07 per 1,000 mammograms among women aged 70 to 84 years.77

Imaging

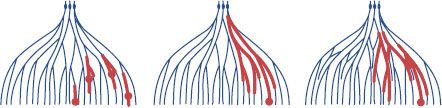

Ninety-five percent of new cases of DCIS present with mammographic abnormalities, of which microcalcifications are most typical.78 Noncalcified mammographic abnormalities make up the remaining findings, with asymmetric densities identified in 10%, dominant masses in 8%, and abnormal galactograms (performed for evaluation of nipple discharge) in 6%. Amorphous, coarse, fine pleomorphic, and fine linear are all forms of calcifications that that can be related to DCIS. Linear and segmental calcifications are considered suspicious distribution and can be associated with DCIS in up to 80% of cases.79 Linear and branching calcifications frequently are associated with high-grade DCIS and necrosis, whereas fine and granular calcifications are associated more commonly with low-grade DCIS80–83 (Fig. 55.1A,B).

Initial evaluation should include magnification views that allow for complete characterization of mammographic findings and determination of the need for biopsy. The extent of the lesion as determined mammographically may be used as a guide for excision; however, the size typically is underestimated by 1 to 2 cm when compared with pathologic measurements.81,84,85 Prior to 2000, MRI was not considered a useful imaging modality for DCIS. However, change in MRI imaging acquisition and an improved understanding of non-masslike malignant lesion imaging characteristics now has MRI considered a valuable imaging tool for DCIS.86 MRI now presents as the imaging modality with the highest sensitivity to detect DCIS, particularly high-grade DCIS. MRI has additionally been shown to better establish the extent of DCIS, thus aiding treatment planning.87 In cases that present with nipple discharge and a negative mammogram, galactography may be helpful in determining the likelihood of underlying DCIS versus papilloma88 (Fig. 55.1C).

Pathology and Biology

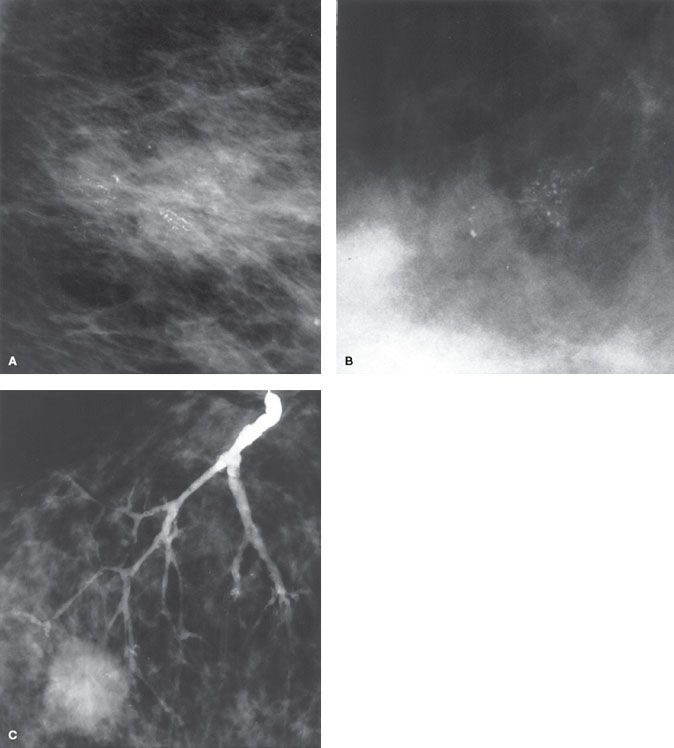

The histologic diversity of DCIS can lead to difficulty in distinguishing it from other pathologic entities.69,70 The spectrum of DCIS extends from noncomedo, low-grade DCIS that can be similar in appearance to atypical ductal hyperplasia to comedo, high-grade DCIS. In addition, DCIS can extend into lobules, making it difficult to distinguish from LCIS.89 Traditionally, classification of DCIS has followed its architectural or morphologic appearance. The five subtypes of DCIS are comedo, solid, cribriform, micropapillary, and papillary,69,70,90 and it is common to encounter a mixture of subtypes within the same specimen.88 The characteristic features of each type are shown in Figure 55.2. Less common subtypes have been described and include apocrine, neuroendocrine, signet-cell cystic hypersecretory carcinoma, and clinging DCIS.91

In 1997, a consensus conference committee was convened to reach an agreement on the pathologic classification of DCIS and the identification of specific features that may convey prognostic significance.68 Methods of processing and evaluating the pathologic specimen were also addressed. Rather than endorsing any specific classification system, the committee recommended and described features that should be documented for each case of DCIS, thus separating out important pathologic components and providing a comprehensive evaluation of the pathologic findings. These features include nuclear grade, presence of necrosis, polarization, and architectural pattern(s). The committee extended its recommendations to include margin status, lesion size, extent of microcalcifications, and correlation between specimen x-ray and mammographic findings. The DCIS Working Party of the EORTC arrived at similar conclusions and emphasized the importance of cytonuclear and architectural differentiation.92

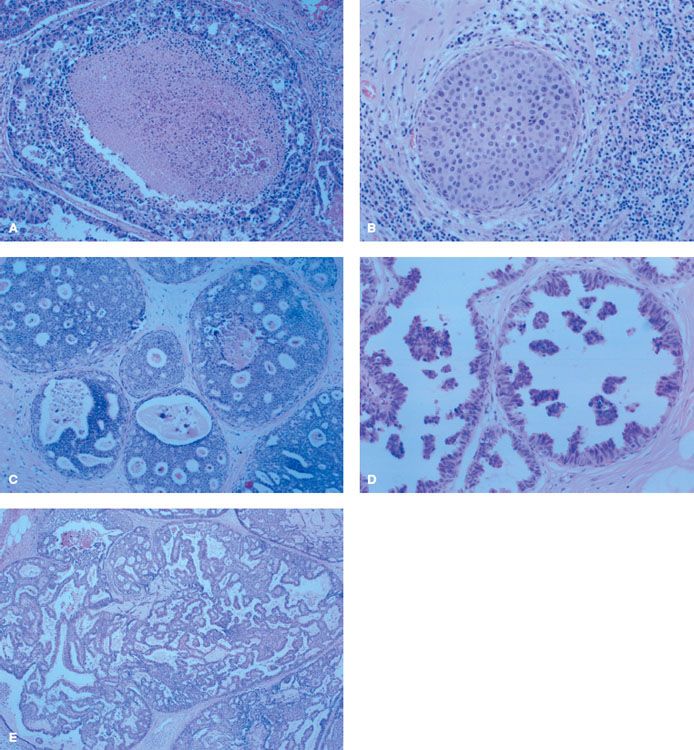

Three-dimensional examination and reconstruction techniques have resulted in a better understanding of the enormously complex structure of the mammary duct–lobular system and the patterns by which DCIS can spread within the breast6,84,93 (Fig. 55.3). Knowledge of the anatomy and distribution of DCIS within the mammary ductal tree can be useful in selecting patients for breast conservation and assuring maximal surgical clearance of the lesion while preserving an acceptable cosmetic result. For example, Ohtake et al.6,84 studied the duct–lobular system with computer graphic reconstruction and found that the breast consists of 16 to 24 duct–lobular systems, each culminating in a corresponding collecting duct at the nipple. They also identified ductal anastomoses that established a connection between the various ductal–lobular units and provided a potential pathway for tumor extension and subsequent diffuse involvement.6,84 Their proposed model for the development of widespread intraductal tumor extension within the breast is seen in Figure 55.4.

Faverly et al.94 have described the DCIS growth pattern within the ductal tree and the implications for surgical excision. The growth patterns documented include unicentric (one area only), multicentric (two distinct areas separated by >4 cm), continuous (extension along ductal system without gaps), and discontinuous or multifocal (two or more areas separated by <4 cm). They found that in mammographically detected DCIS, a multicentric growth pattern was rare (<2%), with most cases showing an even distribution between discontinuous and continuous growth patterns. Of cases with a discontinuous growth pattern, 63% had foci separated by gaps that measured <5 mm, 83% had foci separated by <10 mm, and only 8% had foci separated by >10 mm. There was a correlation between differentiation and growth pattern such that 90% of poorly differentiated DCIS showed a continuous growth pattern, whereas 70% of well-differentiated DCIS had a discontinuous growth pattern. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that a 1-cm margin of normal tissue around the lesion would lead to complete surgical clearance of histologically evident DCIS in 90% of cases. DCIS is a precursor lesion to invasive ductal carcinoma and exists along an evolutionary continuum that starts with benign breast tissue and ends with an invasive breast carcinoma.95 This concept has been validated in several ways. For years, pathologists have recognized and documented confirmation of a histologic progression from benign breast cells to invasive breast cancer. The evolutionary concept is supported by the recognized association between the presence of DCIS and the subsequent increased risk of developing an invasive breast cancer.75,96,97 In some series, a 10-fold risk of developing an invasive lesion has been reported. At the biologic and molecular level, many studies have demonstrated that DCIS and invasive breast cancer are highly similar at the cellular and molecular levels.95,98–100,101–102 These similarities have now been shown to extend to global gene expression profiles as DCIS has been classified under luminal, basal, and erbB2 intrinsic molecular subtypes.98,103 Additionally, these shared identical genetic abnormalities between DCIS and synchronous invasive breast cancer demonstrate a clonal relationship of biologic progression.75,96,97,104 The biologic evolution from benign breast cells to invasive breast cancer occurs through highly diverse genetic mechanisms.

FIGURE 55.1. A: Linear and branching calcifications frequently associated with high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). B: Fine and granular calcifications commonly associated with low-grade DCIS. C: Galactogram with the multiple filling defects associated with DCIS.

FIGURE 55.2. A: Comedo ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) characterized by central necrosis, large cells, and poorly differentiated nuclei. B: Solid DCIS characterized by ductal spaces filled with neoplastic cells with limited necrosis. C: Cribriform DCIS characterized by microlumens and fenestrations. D: Micropapillary DCIS characterized by intraluminal projections with no fibrovascular core. E: Papillary DCIS characterized by intraluminal projections with a fibrovascular core.

Genetic and molecular differences have been documented that differentiate DCIS from normal breast tissue. Genetic alterations have been evaluated with an analysis of loss of heterozygosity that has demonstrated gain or loss of multiple loci.96,97,104–106 Loss of heterozygosity is not seen in normal breast tissue. The frequency of loss of heterozygosity correlates with histologic progression of breast tissue from benign to malignant. Loss of heterozygosity is seen in approximately 50% of atypical ductal hyperplasia. Among specimens harvested from cancerous breasts, 77% of noncomedo and 80% of comedo DCIS lesions share loss of heterozygosity with the synchronous invasive lesion in at least one locus.104

Molecular markers have been studied in DCIS and are found to have a heterogeneous distribution of expression.75 The estrogen receptor is present in 70% of DCIS; however, the rate of expression is higher in low-grade lesions (90%) than in high-grade lesions (25%). This association with histologic grade is reversed for the rate of overexpression of HER2/neu proto-oncogene and the p53 tumor suppression gene. Approximately 50% of all DCIS lesions have overexpression of HER2/neu, and in 25% the p53 tumor suppressor gene is also detected. Both of these molecular markers are noted in <20% of low-grade lesions but are present in approximately two-thirds of high-grade lesions.

Alterations in the surrounding breast parenchyma may also be seen with DCIS. High-grade DCIS, in particular, has been associated with the breakdown of the myoepithelial cell layer and basement membrane surrounding the ductal lumen,107 proliferation of fibroblasts, lymphocyte infiltration, and angiogenesis in the surrounding stromal tissues.108,109 Whether these stromal changes reflect important steps that facilitate primary tumor transformation or secondary alterations in response to ductal epithelium that is being transformed is unknown. Quantitative changes in the expression of genes related to cell motility, adhesion, and extracellular-matrix composition—all of which may be related to the acquisition of invasiveness—occur as DCIS evolves into invasive carcinoma.110

Data suggest that DCIS represents a stage in the development of breast cancer in which most of the molecular changes that characterize invasive breast cancer are already present, although the lesion has not yet assumed a fully malignant phenotype. A final set of events, which probably includes gain of function by malignant cells and loss of function and integrity by surrounding normal tissues, is associated with the transition from a preinvasive DCIS lesion to invasive cancer. Most, if not all, clinically relevant features of breast cancer, such as hormone-receptor status, the level of oncogene expression, and histologic grade, are probably determined by the time that DCIS has evolved.111–114

An occult microinvasive tumor (one that does not exceed 0.1 cm in diameter) may be seen with some cases of DCIS. Such cases are classified as microinvasive breast cancer115 and are generally treated according to the guidelines for invasive disease. Occult microinvasive tumors are most common in patients with DCIS lesions that are >2.5 cm in diameter,116 those presenting with palpable masses or nipple discharge, and those with high-grade DCIS or comedonecrosis.88,117

FIGURE 55.3. All ducts and their branches in an autopsy breast, viewed en face. Each Roman numeral refers to a different independent duct system. (From Going JJ, Moffat DF. Escaping from flatland: clinical and biological aspects of human mammary duct anatomy in three dimensions. J Pathol 2004;203:538–544. Reprinted by permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc., a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)

FIGURE 55.4. Models for the formation of widespread intraductal tumor extension over multiple mammary duct–lobular systems. Narrow line, normal mammary duct–lobular systems; bold line, intraductal tumor extension; closed circle, invasive tumor foci. Left: Multicentric development. Middle: Unicentric development with continuous intraductal tumor extension. Right: Unicentric development with continuous intraductal tumor extension through ductal anastomoses connecting adjacent duct–lobular systems. (From Ohtake T, Abe R, Kimijima I, et al. Intraductal extension of primary invasive breast carcinoma treated by breast-conservation surgery. Cancer 1995;76:32–45, with permission. Reprinted by permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc., a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.)