The Presentation

Diagnosis of breast cancer in the elderly is made by the discovery of a lump in 60–80% women. Since screening is applied less rigorously to elderly patients, the majority of women present with a palpable lump. Several studies have revealed that the stage at presentation is more advanced in elderly women.1, 2 A patient care evaluation survey was conducted by the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons for 1983 and 1990.3 They surveyed all States of USA, including Puerto Rico, and Canada and studied 17 029 women in 1983 and 24 004 women in 1990. Some 20% women in 1983 and 23% in 1990 were 75 years of age or older. The survey included 2000 hospitals (25 patients from each). The percentage of cancers detected by physicians’ examination decreased in the younger group from 27% in 1983 to 21% in 1990, whereas in the elderly the corresponding figures were 41 and 34%, respectively.

Veronesi’s group in Milan reported various features of presentation and choice of therapy in the elderly.4 They studied 2999 postmenopausal patients referred for surgery at the European Institute of Oncology, Milan, from 1997 to 2002. The patients were grouped according to age: young postmenopausal (YPM, age 50–64 years, n = 2052), older postmenopausal (OPM, age 65–74 years, n = 801) and elderly postmenopausal (EPM, age ≥75 years, n = 146). EPM patients had larger tumours compared with YPM patients (pT4: 6.7 versus 2.4%) and more nodal involvement (lymph node positivity: 62.5 versus 51.3%). EPM patients showed a higher degree of estrogen and progesterone receptor expression, less peritumoral vascular invasion and less human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2)/neu expression than YPM patients. Although comorbidities were more often recorded for elderly patients (72% EPM versus 45% YPM), this did not influence surgical choices, which were similar across groups (breast conservation: 73.9, 76.9 and 72.9%, respectively). No systemic therapy was recommended for 19.1% of the EPM group compared with 5.4 and 4.7% of the two other groups. A recent epidemiological study in The Netherlands5 of 127 805 adult female patients with their first primary breast cancer diagnosed between 1995 and 2005 showed that elderly breast cancer patients were diagnosed with a higher stage of disease. Elderly patients underwent less surgery (99.2 versus 41.2%), received hormonal treatment as monotherapy more frequently (0.8 versus 47.3%) and less adjuvant systemic treatment (79 versus 53%).

In women over 70 years of age, estrogen receptor-positive tumours are more common, range 69–95%, compared with all tumours, range 53–72%.3

Pathologically infiltrating ductal carcinoma accounts for 77–85% of all tumours in elderly women compared with 68% in younger women. There is an increase in the proportion of papillary and mucinous carcinoma with advancing age. Whereas the number of lobular carcinoma in situ, comedo, medullary and inflammatory carcinoma decreases with advancing age, the prevalence of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) increases until 75 years, after which it declines.6, 7

In summary, elderly women generally present with large palpable estrogen receptor-positive, infiltrating ductal carcinoma with a positive lymph node.5, 7

Stage of Presentation

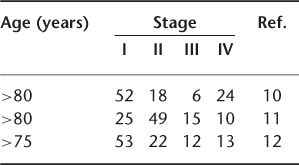

There is generally a delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer in elderly women. In a study by Berg and Robbins,8 the diagnosis was delayed by more than 6 months in 28% of women under 70 years of age compared with 42% in women above the age of 70 years. Similarly, Devitt9 observed a delay of more than 6 months in diagnosis in 35% of women above the age of 70 years compared to 28% below that age. The tumour is generally advanced in the elderly group, as shown in Table 110.1.

Table 110.1 TNM stage (%) with age at presentation.

Variation in Care and Undertreatment in the Elderly

There is growing evidence that there is significant variation in standard care of breast cancer in the elderly and that elderly patients often receive suboptimal treatment. Monica Morrow, in a review on treatment in the elderly, noted that screening by physical examination and mammography is underutilized for the older women.13 Since mastectomy offers excellent local control and has only less than 1% operative mortality in women above 65 years of age, it should be offered to more (suitable) patients. She further pointed out that failure to use adjuvant therapy when indicated is one of the most frequent problems in management of elderly.13

Pattern of care of elderly women is different from that offered to younger patients. In the study by the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons for 1983 and 1990,3 in 1983, 23% of older women received total or partial mastectomy without axillary dissection compared with 8% of younger females. In 1990, the rate of total or partial mastectomy without nodal dissection was 20.6% in older women and 10% in younger women. The use of reconstruction was limited in the older women. The percentage of elderly females receiving reconstruction was 1.2% in 1983 and 1.3% in 1990. The operative mortality rates were higher in the older age-group (2.9% in 1983 and 1.5% in 1990). Radiotherapy was used less frequently in the older group in both study years.

In an editorial in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, Rebecca Silliman chided clinicians for not offering definitive treatment to elderly women with breast cancer.14 Although breast cancer-specific mortality has declined among women younger than 70 years, it is either stable in those aged 70–79 years or increased in women above 65 years of age. This proportion is likely to grow, as older age is the most important risk factor for breast cancer and gains in life expectancy will result in more women being at risk for longer periods. Currently, the average life expectancy of a 75-year-old woman is 12 years (17 years if she is healthy) and that of an 85-year-old is 6 years (9 years if she is healthy). Owing to paucity of good evidence-based data, there is considerable controversy about what constitutes appropriate care for older women. More than one-quarter (27%) of breast cancer deaths in 2001 in the USA were in the age group of 80 years and older. Although the patient’s health status, patient and family preferences and support and patient–physician interactions explain in part age-related treatment variations, age alone remains an independent risk factor for less than definitive breast cancer care.

In a cohort of 407 octogenarian women in Canton of Geneva, Switzerland, Bouchardy et al.15 addressed the relationship between undertreatment and breast cancer mortality. They used tumour registry data, including sociodemographic data, comorbidity, tumour and treatment characteristics and the cause of death. The main problem that they noted in analysing these data was the issue of missing information—20% for comorbidity, 49% for tumour grade and 74% for estrogen receptor (ER) status. Because of loss of data on these important prognostic factors, there was a problem in multivariate analysis and incomplete control of confounding, decreasing the statistical power and precision. Both mastectomy plus adjuvant therapy and breast-conserving surgery plus adjuvant therapy appear to protect against death from causes other than breast cancer, suggesting residual confounding either because comorbidity was not well measured or because undertreatment of breast cancer is associated with undertreatment of other medical conditions. This cohort of Swiss women differed from women presenting elsewhere. The average tumour size in this group was 30 mm, only 22% presented in Stage I, 22% received no therapy and 32% received tamoxifen alone. Despite the limitations of this study, it highlights the link between undertreatment and high rates of breast cancer recurrence and mortality.

A recent retrospective cohort study involving case-note review based on the North Western Cancer Registry database of women aged ≥65 years resident in Greater Manchester with invasive breast cancer registered over a 1 year period (n = 480) showed that even after adjusting for tumour characteristics associated with age by logistic regression analyses, older women were less likely to receive standard management than younger women for all indicators investigated.16 Compared with women aged 65–69 years, women aged ≥80 years with operable (Stage I–IIIa) breast cancer have increased odds of not receiving triple assessment [odds ratio (OR) = 5.5, 95% confidence interval (CI), 2.1–14.5], not receiving primary surgery (OR = 43.0; 95% CI, 9.7–191.3), not undergoing axillary node surgery (OR = 27.6; 95% CI, 5.6–135.9) and not undergoing tests for steroid receptors (OR = 3.0; 95% CI, 1.7–5.5). Women aged 75–79 years have increased odds of not receiving radiotherapy (RT) following breast-conserving surgery compared to women aged 65–69 years (OR = 11.0; 95% CI, 2.0–61.6). These results demonstrate that older women in the UK are less likely to receive standard management for breast cancer compared with younger women and this disparity cannot be explained by differences in tumour characteristics.

In a recent German clinical cohort study, 1922 women aged >50 years with histologically confirmed invasive breast cancer treated at the University of Ulm from 1992 to 2005 were enrolled.17 Adherence to guidelines and effects on overall survival (OAS) and disease-free survival (DFS) for women aged >70 years were compared with those for younger women (aged 50–69 years). The study found that women aged >70 years less often received recommended breast-conserving therapy (70–79 years, 74–83%; >79 years, 54%) than women aged <69 years (93%). Non-adherence to the guidelines on RT (<70 years, 9%; 70–79 years, 14–27%; >79 years, 60%) and chemotherapy (<70 years, 33%; 70–79 years, 54–77%; >79 years, 98%) increased with age. Omission of RT significantly decreased OAS [<69 years, hazard ratio (HR) = 3.29; p < 0.0001; >70 years, HR = 1.89; p = 0.0005] and DFS (<69 years, HR = 3.45; p < 0.0001; >70 years, HR = 2.14; p < 0.0001). OAS and DFS did not differ significantly for adherence to surgery, chemotherapy or endocrine therapy. This study showed that substandard treatment increases considerably with age and omission of RT had the greatest impact on OAS and DFS in the elderly population.

Women suffering from heart disease, obstructive airway disease, stroke or other major incapacitating illnesses receive inadequate diagnostic and therapeutic attention. One study found that the main cause of under treatment in the over-65 age group patients was cited as prohibitive associated medical conditions.18

Nicolucci et al.19 analysed the data on 1724 women treated in 63 general hospitals in Italy. A comorbidity index was computed from individual disease value (IDV) and functional status (FS). IDV summates the severity and presence of specific complications for each disease suffered on a scale of 0–3, with 0 = full recovery and 3 = life-threatening disease. FS from signs and symptoms of 12 system categories evaluated the impact of all conditions, whether diagnosed or not, on patients’ health status. The study showed higher proportions of inadequate diagnosis and therapy in the elderly group. The quality of care was assessed by a score based on observed degree of compliance with standard care. The median value of overall diagnostic and staging score was 60%. About one-third of surgical operations were inappropriate; 24% of cases with Stage I–II disease had unnecessary Halsted mastectomy and breast conservation in smaller tumours of ≤2 cm was underutilized. The presence of one or more coexisting diseases was associated with failure to undergo axillary dissection and lower utilization of conservative surgery.

Alvan Feinstein, a famous clinical epidemiologist from Yale, has said that the failure to classify and analyse comorbid disease has led to many difficulties in medical statistics.20 There are four reasons for measuring comorbidity correctly: (1) to be able to correct for confounding, thus improving the internal validity of the study, (2) to be able to identify effect modification, (3) the desire to use comorbidity as a predictor of outcome and (4) to construct a comprehensive single comorbid scale that is valid, to improve the statistical efficiency. de Groot et al.21 reviewed various comorbidity indices. The following indices have been applied for patients with breast cancer. The Charlson index is the most extensively studied method and includes 19 diseases which are weighted on the basis of strength of association with mortality. The disease count index simply counts the coexisting diseases but lacks a consistent definition and weighting for different diseases. The Kaplan index uses the type and severity of comorbid condition, for example, types are classified vascular (hypertension, cardiac disease, peripheral vascular disease) and non-vascular (lung, liver, bone and renal disease). It has good predictive validity for mortality. It may be worthwhile for all the agencies involved in breast cancer research to adopt one of the above indices and record it prospectively.

Screening in the Elderly

Currently, all women in the UK between ages 50 and 70 years are offered breast cancer screening, which is saving ∼1400 lives every year (2009 NHSBSP Annual Review). Although previously women between 65 and 70 years of age were eligible, they were not offered screening routinely. Extended age pilot schemes are now under way in which the age of inclusion includes women between 47 and 73 years of age. In 2007–08, 16 449 new cancers were detected under this programme. In England, in 2008–09 just under 1.8 million women (aged 45 years and over) were screened within the programme, an increase of 3.5% over 2007–08. The previous 10 years saw the programme grow by 43.9% from 1.2 million in 1998–99. There were 14 166 cases of cancer diagnosed in women screened aged 45 years and over, similar to the previous year (14 110) and nearly double the number in 1998–99 (7561). Of all cancers diagnosed, 11 212 (79.1%) were invasive and of these 5850 (52.2%) were 15 mm or less in size, which could not have been detected by clinical examination alone.

It has been observed that with increasing age the number of screening-detected cancers detected increases (Table 110.2).

Table 110.2 Result of UK breast cancer screening—2004 review NHS Breast Cancer Screening Programme in the UK, 2005.

| Age (years) | Cancer detected per 1000 women screened |

| 50–64 | 7.6 |

| 65–69 | 20.6 |

In order to enhance the rate of breast examination by doctors of women above 65 years of age and to increase compliance with mammography, Herman et al.22 conducted a randomized clinical trial (RCT) at the Metro Health Medical Center, Cleveland, OH. All house staff in Internal Medicine were asked to complete a questionnaire about their attitude towards prevention of breast cancer in elderly people after providing some basic information (monograph and a lecture). In one arm (controls), no specific interventions were offered. In the next group (education), nurses provided educational leaflets to patients attending the clinics. In the third group (prevention), nurses filled the request forms and facilitated women to undergo mammography. The results are given in Table 110.3. The study suggested that encouragement and education of older women by motivated doctors and nurses improves compliance.

Table 110.3 Rates of examination and mammography by intervention.

| Group | Breast examination (%) | Mammography (%) |

| Control (n = 192) | 18 | 18 |

| Education (n = 183) | 22 | 31 |

| Prevention (n = 165) | 32 | 36 |

Chen et al.23 reported the mortality rate of women aged 65–74 years screened in the Swedish two-county trial—77 080 women were randomized to undergo screening every 33 months and 55 985 women served as controls. Of the screened group, 21 925 were in the age group 65–74. In the control arm, 15 344 women belonged to the age group 65–74 years. The relative breast cancer mortality in the screened group was 0.68, demonstrating a survival advantage in the elderly population.

Risk Factors in the Elderly

With advancing age, the risk of developing breast cancer rises. In a cohort of National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project’s breast cancer prevention trial in the USA, the presence of non-proliferative lower category benign breast disease (LCBBD) was found to increase the risk of invasive breast cancer. The overall relative risk (RR) of breast cancer was 1.6 for LCBBD compared with women without any LCBBD. This risk increased to 1.95 (95% CI, 1.29–2.93) among women aged 50 years and over.24

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has been identified as a risk factor for breast cancer. The impact of HRT on the incidence and death due to breast cancer in the UK was assessed through a study of over 1 million women.25 In this prospective cohort of 1 084 110 women aged 50–64, current users of HRT were found to have a higher risk of developing breast cancer than non-users (RR = 1.66; 95% CI, 1.58–1.75). The risk was highest for combined estrogen + progestogen (RR = 2; 95% CI, 1.88–2.12) than for estrogen alone (RR = 1.3; 95% CI, 1.2–1.4) and for tibolone (RR = 1.45; 95% CI, 1.25–1.68) compared with those who never used this treatment. There was a dose–response relationship of increasing risk of cancer with increasing duration of HRT usage, the highest being with combined estrogen + progestogen used for 10 years or more (RR = 2.31; 95% CI, 2.08–2.56).

The Danish Nurses Cohort study26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree