Chapter 1

Breast and Ovarian Cancer Basics

FROM A STRICTLY SCIENTIFIC PERSPECTIVE, women have breasts to feed their babies. Yet, for most of us, our breasts are much more than milk-producing glands. Our emotional attachment to our breasts is considerable, increasing as we move from puberty to maturity. Breasts enhance our physical form, give us sexual pleasure, and help us forge a close maternal bond as we nourish our infants. Although our ovaries aren’t as visible, their reproductive role is more significant, from our first menstrual cycle to monthly fertility and, finally, our change of life. A woman’s breasts and ovaries are uniquely feminine and intensely personal; the threat of cancer in either is particularly scary.

Most Cancers Aren’t Hereditary

People with cancer are often surprised if none of their relatives has been diagnosed, but most cancers aren’t hereditary. The majority are sporadic. They develop from damage that our genes acquire (not inherit) as we age. Genes are fundamental to all living organisms, including humans. They contain instructions for critical body functions and hold all hereditary information that is passed from parent to child. Inherited genetic changes called mutations cause about 5 to 10 percent of breast cancers and 12 percent of ovarian cancers. Most of these hereditary breast and ovarian cancers are caused by mutations in two specific genes, BReast CAncer 1 (BRCA1) and BReast CAncer 2 (BRCA2).1 These mutations are familial (they run in families). They account for only a small percentage of breast and ovarian cancers, yet their presence greatly increases a woman’s risk for both. Multiple diagnoses in a family also raise a woman’s risk. A family history of breast cancer, even when there is no BRCA mutation in the family, increases breast cancer risk. A strong history of ovarian cancer elevates a woman’s risk for that disease.

Most breast and ovarian cancers aren’t hereditary

Sporadic and hereditary cancers differ in important ways that may affect healthcare decisions:

• Hereditary cancer often occurs at an earlier age than the sporadic form of the same cancer.

• Recommendations for cancer screening and risk reduction can differ, and should begin at a younger age for individuals who have an inherited gene mutation or a family history of cancer.

• Multiple family members may inherit the same gene mutation that increases risk for certain hereditary cancers.

• Children can inherit a parent’s gene mutation.

Throughout the remainder of this book, you’ll learn how inherited mutations or a family history affect your risk for cancer and how you can manage that risk.

An Introduction to Breast Cancer

More than a million new cases of breast cancer occur each year worldwide. In the United States, it’s the second most commonly diagnosed cancer (after skin cancer) among women, and it causes more deaths than any other cancer except lung cancer. It also affects men, although far less frequently—less than 1 percent of all breast cancers occur in men.

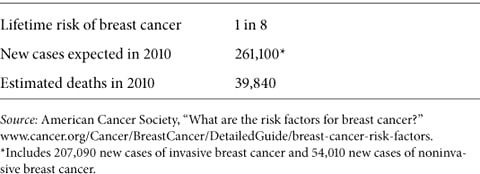

Table 1. U.S. breast cancer statistics

Breast cancer deaths have declined since 1990 because of increased awareness, better methods of early detection, and advances in treatment. Yet too many women, about forty thousand every year, still die from this disease. In the 1970s, a woman living in the United States had a 1 in 11 chance of developing breast cancer in her lifetime; those odds steadily worsened over the next two decades. Since 1999, breast cancer has decreased among women over age 50, while rates among younger women remain unchanged. Today, an average woman’s lifetime risk of developing breast cancer is 1 in 8 (approximately 12.5 percent) (see table 1).

Anatomy of the breast

Breast cancer almost always begins in the lobules (the glands that produce milk) or the ducts (the tubes that carry milk to the nipple). Cancer usually develops over several years, typically without pain or other noticeable symptoms, until it shows up as a suspicious calcification on a mammogram or is found as a lump during a breast exam by a woman or her doctor. A tumor may show itself as it grows: a lump or area of thickness, a change in the size or shape of the breast, a skin irritation or dryness that refuses to heal, or unusual tenderness or discharge from the nipple. These same changes often occur with other conditions and don’t always signal breast cancer.

Types of Breast Cancer

Tumors are either in situ, or invasive. In situ, meaning “in place,” refers to early stage breast cancer that remains within the ducts or the lobules. Nearly all women diagnosed with in situ breast tumors are cured—their cancer isn’t likely to return. Invasive tumors are more worrisome, because if cancerous cells reach the bloodstream or lymph nodes, they can metastasize (spread) to the liver, bones, lungs, and other organs. Treatment is then more involved, and remission or cure is less likely.

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) develops in the milk ducts. About 1 in 5 new breast cancers are DCIS, the earliest stage and most commonly diagnosed in situ breast cancer. Too small to be felt, DCIS is usually found by mammography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Early detection is important because, left untreated, some DCIS develops into invasive breast cancer and may metastasize. If you have DCIS, your risk of developing a new breast cancer or recurrence is higher than that of someone who has never been diagnosed.

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) isn’t considered a true breast cancer. Usually diagnosed in premenopausal women, LCIS involves abnormal cells that signal a higher-than-average risk of developing invasive breast cancer. Rarely found by mammography, LCIS is usually discovered during a breast biopsy to explore a lump, microcalcification (the residue from rapidly dividing cells that may signal an early cancer), or other abnormality.

Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) is cancer that has spread beyond the ducts to the surrounding breast tissue. It’s the most common breast cancer, accounting for about 80 percent of all cases. Although women of any age can develop IDC, it’s more often found after age 55.

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) begins in the lobules and spreads to the breast tissue. Only 10 percent of invasive breast cancers are ILC, which is more often diagnosed in women who are age 60 and older.

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) accounts for only 1 to 3 percent of breast cancers. It often begins with swelling or reddening of the breast rather than a lump. IBC can grow very quickly—symptoms may worsen in a single day—so it’s very important to recognize the signs of this disease and seek prompt treatment. IBC tends to occur at an earlier age than most other breast cancers, on average at age 56 for white women and age 52 for African American women, who are more likely to develop IBC.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree