Chapter Outline

Aspiration of the bone marrow 113

Consent and safety 113

Performing a bone marrow aspiration 113

Puncture of the ilium 114

Puncture of the sternum 114

Comparison of different sites for marrow puncture 114

Aspiration of the bone marrow in children 114

Marrow puncture needles 115

Processing of aspirated bone marrow 116

Preparing films from bone marrow aspirates 116

Concentration of bone marrow by centrifugation 116

Preparation of films of postmortem bone marrow 117

Examination of aspirated bone marrow 117

Principles of marrow aspirate examination 117

Quantitative cell counts on aspirated bone marrow 118

Differential cell counts on aspirated bone marrow 118

Sources of error and physiological variations 118

Cellular ratios 119

Reporting bone marrow aspirate films 119

Preparation of sections of aspirated bone marrow fragments 120

Percutaneous trephine biopsy of the bone marrow 120

Principles behind marrow trephine biopsy examination 120

Imprints from bone marrow trephine biopsy specimens 122

Processing of bone marrow trephine biopsy specimens 123

Staining of sections of bone marrow trephine biopsy specimens 123

Biopsy of the bone marrow is an indispensable adjunct to the study of diseases of the blood and may be the only way in which a correct diagnosis can be made. Marrow can be obtained by needle aspiration, percutaneous trephine biopsy or surgical biopsy. When performed correctly, bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy are simple and safe procedures that can be repeated many times and can be performed on outpatients.

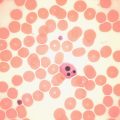

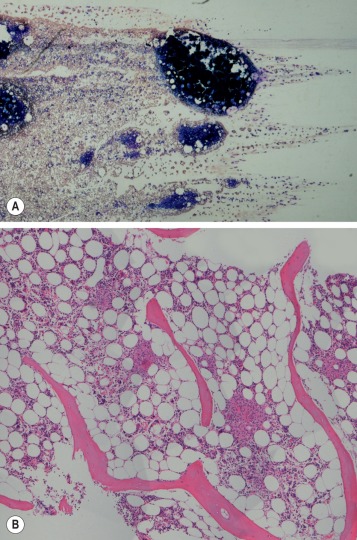

The morphological assessment of aspirated or core biopsy specimens of bone marrow is based on two principles: first, that bone marrow has an organised structure such that in normal health bone marrow cells display distinct numerical and spatial relationships to each other; second, that individual bone marrow cells have distinctive cytological appearances that reflect the lineage and stage of maturation. Each or all of these features may specifically be disordered in disease. The specimens obtained by bone marrow aspiration or by bone marrow trephine biopsy are very different samples ( Fig. 7-1 ) and contribute differently to diagnosis. Trephine biopsies provide excellent appreciation of spatial relationships between cells and of overall bone marrow structure; aspirated material provides information about the numerical and cytological features of marrow cells. It is clear, therefore, that bone marrow aspirate and bone marrow biopsy specimens have important and complementary roles in clinical investigation and may have different relative merits in the assessment of marrow disease. Furthermore, in almost all cases marrow assessment is only one part of the overall diagnostic work-up.

Aspiration of the bone marrow

Satisfactory samples of bone marrow can usually be aspirated from the sternum, iliac crest or anterior or posterior iliac spines. In the majority of patients, the procedure can be performed with local and oral analgesia without recourse to intravenous sedation. In most circumstances the posterior superior iliac spine is the preferred biopsy site and selection of this site has the advantage that, if no material is aspirated, a trephine biopsy can be performed immediately. Biopsy from the posterior iliac spine may, however, be technically difficult in subjects who are obese or immobile, and puncture of the sternum is occasionally necessary. However, for safety reasons, sternal puncture should be used only when there is a very specific indication.

Consent and safety

Consent for the procedure of aspiration or trephine biopsy should take place according to local standard operating procedures, but should always include a discussion of the risks and benefits of the procedure. The risks associated with bone marrow aspiration and biopsy have been assessed using voluntary register data. Results show that risks are not dependent on operator experience and have a low incidence (around 0.1%). However, adverse events continue to be reported and may be severe. The most frequent adverse events relate to haemorrhage and are most often seen in the context of myeloproliferative neoplasms and thrombocytopenia or other bleeding disorders (including the use of antiplatelet agents). , Particular risks are associated with aspiration from the sternum. The operator should be aware of the additional risks and contraindications associated with aspiration from that site. The sternum should not be used as a site of biopsy in children or be used in adults if there is a disorder associated with increased bone resorption, such as myeloma. Operators should also be aware that unless the needle is correctly inserted in the sternum with an appropriate guard, there is a danger of perforating the inner cortical layer and damaging the underlying large blood vessels and right atrium, with serious consequences.

Performing a bone marrow aspiration

Only needles designed for the purpose should be used for marrow aspiration (discussed later). The operator should always wear surgical gloves to obtain a biopsy of bone marrow and should take great care to avoid needlestick injuries. A marrow aspiration or trephine biopsy should be performed in accordance with local guidelines for sterile procedures. Skin around the area should be cleaned, for example, with 70% alcohol or 0.5% chlorhexidine (5% diluted 1 in 10 in ethanol). Infiltrate the skin, subcutaneous tissue and periosteum overlying the selected site with a local anaesthetic such as 2–5 ml of 2% lidocaine. Wait until anaesthesia has been achieved. With a boring movement, pass the needle perpendicularly into the cavity of the ilium at the centre of the oval posterior superior iliac spine or 2 cm posterior and 2 cm inferior to the anterior superior iliac spine. When the bone has been penetrated, remove the stilette, attach a 1 ml syringe and suck up marrow contents for making films. If a larger sample is needed (e.g. for cytogenetic or immunophenotypic analysis), attach a second 5 or 10 ml syringe and aspirate a second sample. As a rule, material can be sucked into the syringe without difficulty; occasionally it may be necessary to reinsert the stilette, push the needle in a little further and suck again. Failure to aspirate marrow – a ‘dry tap’ – suggests bone marrow fibrosis or infiltration. Computed tomography–guided marrow sampling may be helpful in patients who are obese, in whom it is difficult to locate the iliac spines.

Because bone marrow clots faster than peripheral blood, films should be made from the aspirated material without delay at the bedside. The remainder of the material may then be delivered into a bottle containing an appropriate amount of ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA) anticoagulant and used later to make more films. Preservative-free heparin should be used rather than EDTA if immunophenotyping or cytogenetic studies are needed. Some material can be preserved in fixative rather than anticoagulant for preparation of histological sections (see p. 123 ). Fix some of the films in absolute methanol as soon as they are thoroughly dry for subsequent staining by a Romanowsky method or Perls stain for iron. Appropriately fixed films are also suitable for cytochemical staining ( Chapter 15 ). If there has been a ‘dry tap’, insert the stilette into the needle and push any material in the lumen of the needle onto a slide and spread it; in lymphomas and carcinomas, especially, sufficient material may be obtained using this approach to allow a diagnosis. Squash preparations of marrow fragments can be a useful supplement to bone marrow films and one such preparation should be made from each marrow aspirate. In preparing a squash preparation, a drop of aspirated marrow is placed in the centre of a slide and, unless the aspirate is very cellular, the fragments are concentrated by removing the more dilute part of the aspirate with a plastic pipette. A second slide is then placed on top of the first and the fragments are crushed by rotating one slide on the other. Both wedge-spread films and squashes are then fixed and stained. Bone marrow aspirates in adults can be performed from the ilium, the sternum or the spinous processes of the vertebrae; the latter site is rarely used and the procedure is described in the 10th edition of this book.

Puncture of the ilium

The usual sites for puncture in adults are the posterior superior and, less commonly, the anterior superior iliac spine. If serial punctures are being performed, a different site should be selected for each puncture to avoid aspirating marrow that has been diluted by intramedullary haemorrhage resulting from previous punctures. The posterior iliac spine overlies a large marrow-containing area and relatively large volumes of marrow can be aspirated from this site. Posterior iliac puncture can be carried out with the patient lying sideways, as for a lumbar puncture, or prone. The anterior superior iliac spine may be easier to locate in individuals who are very obese and the bone overlying it is said to be thinner than that of the iliac crest.

Puncture of the sternum

The specific risks of sternal marrow aspiration were discussed earlier (see p. 113 ). Puncture of the sternum must be performed with care to avoid pushing the aspiration needle through the bone. The usual site for puncture is the manubrium or the first part of the body of the sternum. It is essential to use a needle with a guard that cannot slip, such as a Klima type. After piercing the skin and subcutaneous tissues, when the needle point reaches the periosteum, adjust the guard on the needle to allow it to penetrate about 5 mm further. If the guard cannot be advanced to this extent, it is not safe to proceed. Push the needle with a boring motion into the cavity of the bone. It is usually easy to appreciate when the cavity of the bone has been entered. Aspiration is then carried out as described earlier.

Comparison of different sites for marrow puncture

There is considerable variation in the composition of cellular marrow withdrawn from adjacent or different sites. Aspiration from only one site may give misleading information; this is particularly true in aplastic anaemia since the marrow may be affected patchily. In general, however, the overall cellularity, the haemopoietic maturation pathways and the balance between erythropoiesis and leucopoiesis are similar at all sites. In practice, it is an advantage to have a choice of several sites for puncture, particularly when a potential site has been previously irradiated, when a puncture at one site results in a ‘dry tap’ or when only peripheral blood is withdrawn. Aspiration at a different site may yield cellular marrow or strengthen suspicion of a widespread change affecting the bone marrow, such as fibrosis or hypoplasia. In aplastic anaemia an aspirate may not be fully informative and a trephine biopsy should also be performed.

Aspiration of the bone marrow in children

Iliac puncture, particularly in the region of the posterior superior spine, is usually the method of choice in children. Occasionally, in an older child who is obese, the posterior superior iliac spine cannot be felt. In this case a satisfactory sample usually can be obtained from the anterior ilium. In small babies, marrow can be withdrawn from the medial aspect of the upper end of the tibia just below the level of the tibial tubercle. This site should be used with caution because it is vulnerable to fractures and laceration of the adjacent major blood vessels. In older children, the tibial cortical bone is usually too dense and the marrow within is normally less active. It must be remembered that sternal puncture in children should be avoided because the bone is thin and the marrow cavities are small.

Marrow puncture needles

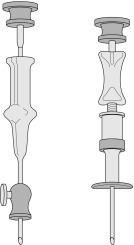

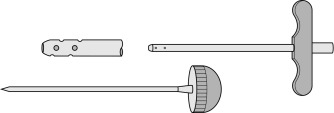

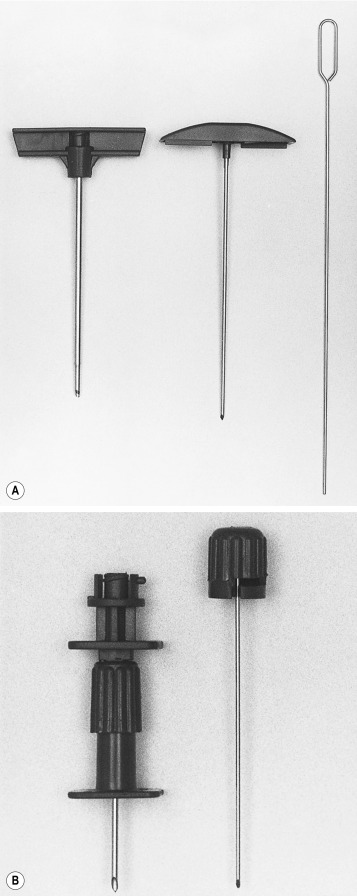

Needles should be stout and made of hard stainless steel, about 7–8 cm in length, with a well-fitting stilette and they must be provided with an adjustable guard. With reusable needles, the point of the needle and the edge of the bevel must be kept well sharpened. The most common reusable needles are the Salah and Klima needles ( Fig. 7-2 ). A slightly larger needle with a T-bar handle at the proximal end was developed by Islam ( Fig. 7-3 ); it provides a better grip, is more manoeuvrable and is more successful for biopsies of excessively hard (e.g. osteosclerotic) or soft (e.g. profoundly osteoporotic) bone. A modified version of the Islam needle has multiple holes in the distal portion of the shaft in addition to the opening at the tip to overcome sampling error when the marrow is not uniformly involved in a pathological lesion. Several types of disposable bone marrow aspiration and trephine biopsy needles are now available; their design is similar to that of the traditional reusable needles ( Fig. 7-4 ). The increasing use of disposable needles by haematologists is based on considerations of safety for patient and operator.

Processing of aspirated bone marrow

There is little advantage in aspirating more than 0.3 ml of marrow fluid from a single site for morphological examination because this increases peripheral blood dilution. If large amounts of marrow are needed for several tests, such as immunophenotyping, cytogenetic analysis and molecular studies, the syringe can be detached from the aspiration needle and the stilette can be replaced, leaving the aspiration needle in the bone. After the marrow smears have been prepared, the same or another syringe can be attached to the needle and another 5–10 ml of marrow can be aspirated.

It is good practice to obtain a sample of peripheral blood from the patient at the same time as the bone marrow so that films from both specimens can be examined and stored together. This can be done simply by preparing some films from blood obtained from a finger prick after completing the bone marrow sampling or by venepuncture so that a full blood count can be obtained. The blood film should be permanently stored with the bone marrow films.

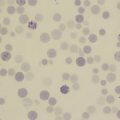

Preparing films from bone marrow aspirates

Make films, 3–5 cm in length, of the aspirated marrow using a smooth-edged glass spreader no more than 2 cm in width ( Fig. 7-5 ). The marrow fragments are dragged behind the spreader and leave a trail of cells behind them. Spreading should be toward the area to which the label is to be applied to avoid having particles dragged to the tip of the slide, where it is difficult to examine them. If there are insufficient fragments, they can be concentrated. This is not usually necessary for marrows that are very cellular such as in acute and chronic myelogenous leukaemia and megaloblastic anaemia. Concentration of marrow can be achieved by delivering single drops of aspirate onto slides about 1 cm from one end. Most of the blood is quickly sucked off from the edge of the drop with the marrow syringe or a fine plastic pipette. The irregularly shaped marrow fragments tend to be left behind on the slide and can be lifted off with the spreader; films can then be prepared as explained earlier.

After thorough drying, fix the films of bone marrow and stain them with Romanowsky dyes, as for peripheral blood films. However, a longer fixation time (at least 20 min in methanol) is essential for high-quality staining. If a film needs to be stained urgently, fix and stain one film only and permit the others to dry thoroughly. This avoids having all films showing artefacts caused by fixation of slides before thorough drying has been achieved. Films can also be stained by Perls method (see p. 313 ) to demonstrate the presence or absence of iron.

The preparation can be considered satisfactory only when marrow particles and free marrow cells can be seen in stained films. It is in the cellular trails that differential counts should be made, commencing from the marrow fragment and working back toward the head of the film; in this way, smaller numbers of cells from the peripheral blood are included in a differential count.

When the aspirated marrow is put into an anticoagulant in a tube (e.g. EDTA) care should be taken that appropriate amounts are used for the volume of marrow to be anticoagulated. When films of marrow containing a gross excess of anticoagulant are spread (as when a few drops of marrow are added to a tube containing sufficient EDTA to prevent the clotting of 5 ml of blood), masses of pink-staining amorphous material may be seen and some of the erythroblasts and reticulocytes may clump together.

Concentration of bone marrow by centrifugation

Centrifugation can be used to concentrate the marrow cells and to assess the relative proportions of marrow cells, peripheral blood and fat in aspirated material. Although concentration of poorly cellular samples is useful, especially when an abnormal cell is present in small numbers, it is unnecessary when the aspirated material is of average or increased cellularity. Volumetric data, too, are of little value in individual patients because of the wide range of values encountered, even in health. Methods for separation of marrow cells are described on page 58.

Preparation of films of postmortem bone marrow

Films made of bone marrow obtained postmortem are seldom satisfactory. If satisfactory results are to be achieved, the procedure must be carried out as soon after death as possible. When the marrow is spread in the ordinary way, the majority of the cells tend to disintegrate and appear as smears. The rate and pattern of cellular autolysis during the first 15 h after death have been studied and the differences between the changes of postmortem autolysis and those that occur in life as a result of blood diseases have been defined. Blood cells are much better preserved if a small piece of marrow is suspended in 1–2 ml of 5% bovine albumin (1 volume of 30% albumin, 5 volumes of 9 g/l NaCl). The suspension is then centrifuged and the deposited marrow cells are resuspended in a volume of supernatant approximately equal to, or slightly less than, that of the deposit. Films are made of this suspension in the usual way.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree