Chapter 5 Blood cell morphology in health and disease

Examination of blood films

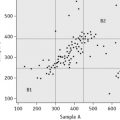

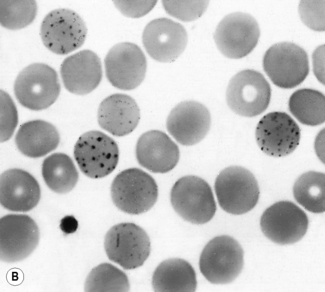

Having selected a suitable area, a ×40 or ×50 objective or ×60 oil-immersion objective should then be used. A much better appreciation of variation in red cell size, shape and staining can be obtained with one of these objectives than with the ×100 oil-immersion lens. It should be possible to detect features such as toxic granulation or the presence of Howell–Jolly bodies or Pappenheimer bodies. The major part of the assessment of a blood film is usually done at this power. The ×100 objective in combination with ×6 or ×10 eyepieces should be used only for the final examination of unusual cells and for looking at fine details such as basophilic stippling (punctate basophilia) or Auer rods. Whether it is necessary to examine a film with a ×100 objective depends on the clinical features, the blood count and the nature of any morphologic abnormality detected at lower power (Fig. 5.1).

Red cell morphology

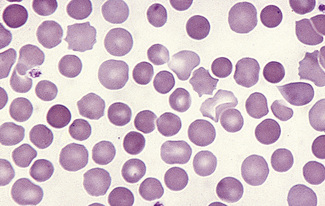

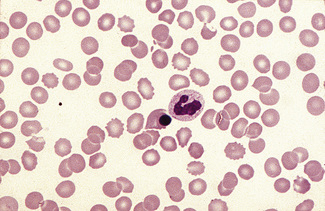

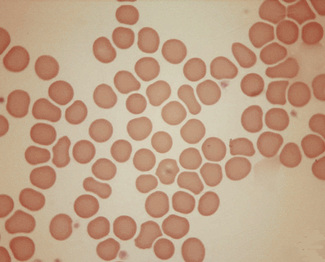

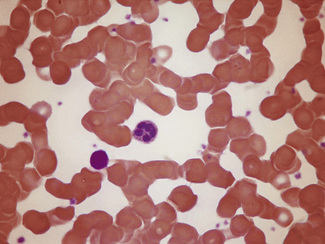

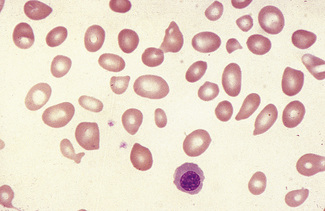

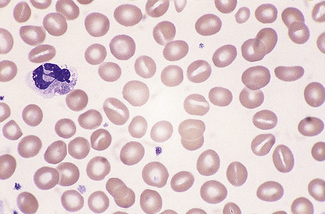

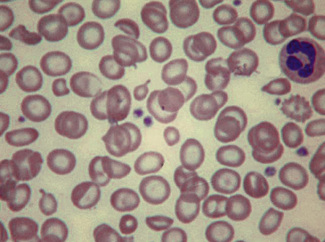

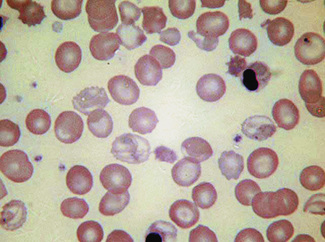

In health, the red blood cells vary relatively little in size and shape (Fig. 5.1). In well-spread, dried and stained films the great majority of cells have round, smooth contours and diameters within the comparatively narrow range of 6.0–8.5 μm. As a rough guide, normal red cell size appears to be about the same as that of the nucleus of a small lymphocyte on the dried film (Fig. 5.1). The red cells stain quite deeply with the eosin component of Romanowsky dyes, particularly at the periphery of the cell as a result of the cell’s normal biconcavity. A small but variable proportion of cells in well-made films (usually <10%) are definitely oval rather than round, and a very small percentage may be contracted and have an irregular contour or appear to have lost part of their substance as the result of fragmentation (schistocytes). According to Marsh, the percentage of ‘pyknocytes’ (irregularly contracted cells) and schistocytes in blood from healthy adults does not exceed 0.1% and the proportion is usually considerably less than this, whereas in normal, full-term infants the proportion is higher, 0.3–1.9%, and in premature infants it is still higher, up to 5.6%.1

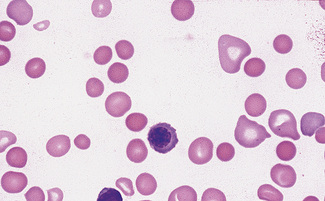

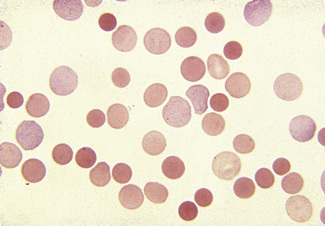

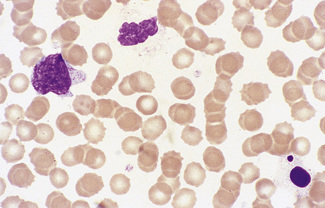

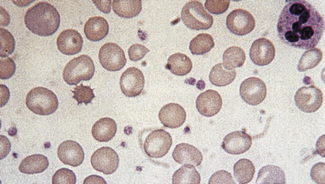

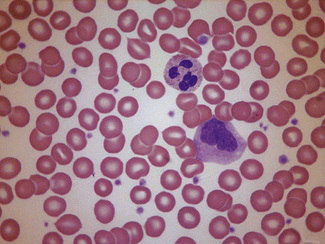

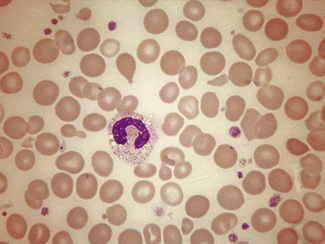

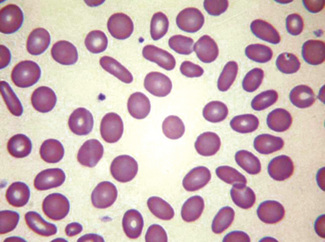

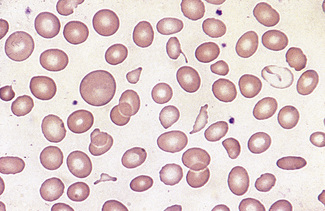

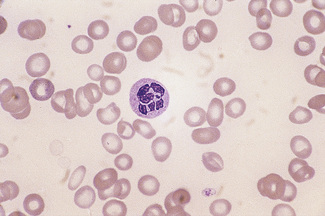

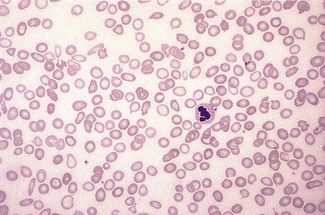

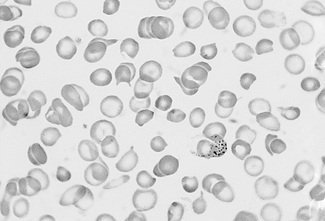

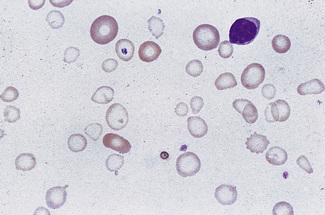

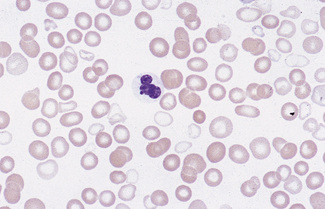

Normal and pathological red cells are subject to considerable distortion in the spreading of a film and, as already mentioned, it is imperative to scan films carefully to find an area where the red cells are least distorted before attempting to examine the cells in detail. Such an area can usually be found toward the tail of the film, although not actually at the tail. Rouleaux often form rapidly in blood after withdrawal from the body and may be conspicuous even in films made at a patient’s bedside. They are particularly noticeable in the thicker parts of a film that have dried more slowly. Ideally, red cells should be examined in an area in which there are no rouleaux and the red cells are touching but with little overlap. The film in the chosen area must not be so thin as to cause red cell distortion; if the tail of the film is examined, a false impression of spherocytosis may be gained. The varying appearances of different areas of the same blood film are illustrated in Figures 5.2–5.4. The area illustrated in Figure 5.2 would clearly be the best for looking at red cells critically.

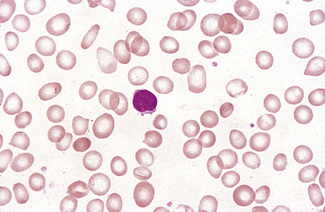

Figure 5.3 Photomicrograph of a blood film showing an area that is too thin for examination (same film as Fig. 5.2).

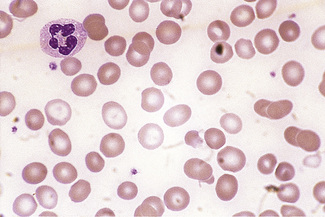

Figure 5.4 Photomicrograph of a blood film showing an area that is too thick for examination (same film as Fig. 5.2).

The advantages and disadvantages of examining red cells suspended in plasma have been referred to briefly in Chapter 4 (see p. 63). By this means, red cells can be seen in the absence of artefacts produced by drying, and abnormalities in size and shape can be better and more reliably appreciated than in films of blood dried on slides. However, the ease and rapidity with which dried films can be made, and their permanence, give them an overwhelming advantage in routine studies.

In disease, abnormality in the red cell picture stems from four main causes, which lead to characteristic cytological abnormalities (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Mechanisms of red cell abnormalities and resultant cytological features

| Cause | Resultant abnormality |

|---|---|

| Attempts by the bone marrow to compensate for anaemia by increased erythropoiesis | Signs of less mature cells in the peripheral blood (polychromasia and erythroblastaemia) |

| Inadequate synthesis of haemoglobin | Reduced or unequal haemoglobin content and concentration (hypochromia, anisochromasia or dimorphism) |

| Abnormal erythropoiesis, which may be effective or ineffective | Increased variation in size (anisocytosis) and shape (poikilocytosis), basophilic stippling, sometimes dimorphism |

| Damage to, or changes affecting, the red cells after leaving the bone marrow, including the effects of reduced or absent splenic function | Spherocytosis, irregular contraction, elliptocytosis, ovalocytosis or fragmentation (schistocytosis); the presence of Pappenheimer bodies, Howell–Jolly bodies and variable numbers of certain specific poikilocytes (target cells, acanthocytes and spherocytes) |

Abnormal erythropoiesis

Anisocytosis (αυισoζ, unequal) and Poikilocytosis (πoικιλoζ, varied)

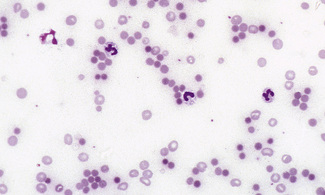

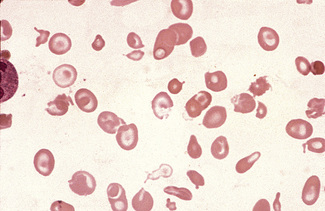

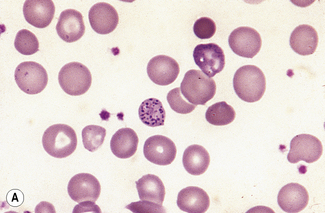

Anisocytosis and poikilocytosis are non-specific features of almost any blood disorder. The terms imply more variation in size or shape than is normally present (Figs 5.5, 5.6). Anisocytosis may be a result of the presence of cells larger than normal (macrocytosis), cells smaller than normal (microcytosis) or both; frequently both macrocytes and microcytes are present (Fig. 5.5).

Poikilocytes are produced in many types of abnormal erythropoiesis, for example, megaloblastic anaemia (Fig. 5.7), iron deficiency anaemia, thalassaemia, myelofibrosis (both idiopathic and secondary) (Fig. 5.8), congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia (Fig. 5.9) and the myelodysplastic syndromes. Elliptocytes and ovalocytes are among the poikilocytes that may be present when there is dyserythropoiesis; they are often present in megaloblastic anaemia (macro-ovalocytes) and in iron deficiency anaemia (‘pencil cells’), but they may also be seen in myelodysplastic syndromes and in primary myelofibrosis (Fig. 5.8). The number of elliptocytes and teardrop poikilocytes has been observed to correlate with the severity of iron deficiency anaemia.2 Poikilocytes are not only characteristic of disordered erythropoiesis but are also seen in various congenital haemolytic anaemias caused by membrane defects and in acquired conditions such as microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia and oxidant damage; in these disorders, the abnormality of shape results from damage to cells after formation and is described later in this chapter.

Macrocytes

Classically found in megaloblastic anaemias (Fig. 5.10), but macrocytes are also present in some cases of aplastic anaemia, myelodysplastic syndromes and other dyserythropoietic states. In patients being treated with hydroxycarbamide (previously known as hydroxyurea) the red cells are often macrocytic. A common cause of macrocytosis is excess alcohol intake, and it occurs in alcoholic and other types of chronic liver disease. In these conditions, the red cells tend to be fairly uniform in size and shape and there may also be stomatocytes (Fig. 5.11). In the rare type III form of congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia, some of the macrocytes are exceptionally large. Another rare cause of macrocytosis is benign familial macrocytosis.3 Macrocytosis also occurs whenever there is an increased rate of erythropoiesis, because of the presence of reticulocytes. Their presence is suspected in routinely stained films because of the slight basophilia, giving rise to polychromasia (see p. 86) and is easily confirmed by special stains (e.g. New methylene blue, see p. 33). These polychromatic macrocytes should be distinguished from other macrocytes because the diagnostic significance is quite different.

Microcytes

The presence of microcytes usually results from a defect in haemoglobin formation. Microcytosis is characteristic of iron deficiency anaemia (Fig. 5.12), various types of thalassaemia (Fig. 5.13), and severe cases of anaemia of chronic disease. Causes that are rarer include congenital and acquired sideroblastic anaemias. Microcytosis related to a defect in haemoglobin synthesis should be distinguished from red cell fragmentation or schistocytosis (see p. 80). Both abnormalities can lead to a reduction of the mean cell volume (MCV). However, it should be noted that a low MCV is common in association with a defect in haemoglobin synthesis, whereas it is uncommon in fragmentation syndromes because the fragments usually comprise only a small percentage of erythrocytes.

Basophilic Stippling

Basophilic stippling or punctate basophilia means the presence of numerous basophilic granules distributed throughout the cell (Fig. 5.14); in contrast to Pappenheimer bodies (see below), they do not give a positive Perls’ reaction for ionized iron. Punctate basophilia has quite a different significance from diffuse cytoplasmic basophilia. It is indicative of disturbed rather than increased erythropoiesis. It occurs in many blood diseases: thalassaemia, megaloblastic anaemias, infections, liver disease, poisoning by lead and other heavy metals, unstable haemoglobins and pyrimidine-5′-nucleotidase deficiency.4

Inadequate haemoglobin formation

Hypochromia (Hypochromasia) (υπoρ, under)

The term hypochromasia, or now, more often, hypochromia, refers to the presence of red cells that stain unusually palely. (In doubtful cases, it is wise to compare the staining of the suspect film with that of a normal film stained at the same time.) There are two possible causes: a lowered haemoglobin concentration and abnormal thinness of the red cells. A lowered haemoglobin concentration results from impaired haemoglobin synthesis. This may stem from failure of haem synthesis – iron deficiency is a very common cause (Fig. 5.15) and sideroblastic anaemia (Fig. 5.16) is a rare cause – or failure of globin synthesis as in the thalassaemias (Fig. 5.17). Haemoglobin synthesis may also be impaired in chronic infections and other inflammatory conditions. Abnormally thin red cells (leptocytes) (see p. 82) can be the result of a defect in haemoglobin synthesis (e.g. in thalassaemias and iron deficiency) but they also occur in liver disease. It cannot be too strongly stressed that a hypochromic blood picture does not necessarily mean iron deficiency, although this is the most common cause. In iron deficiency, the red cells are characteristically hypochromic and microcytic, but the extent of these abnormalities depends on the severity; hypochromia may be minor and may be overlooked if the haemoglobin concentration (Hb) exceeds 100 g/l. In heterozygous or homozygous α+ thalassaemia, heterozygous α° thalassaemia or heterozygous β thalassaemia, hypochromia is often less marked, in relation to the degree of microcytosis, than in iron deficiency. The presence of target cells or basophilic stippling also favours a diagnosis of thalassaemia trait rather than iron deficiency. In homozygous β thalassaemia, the abnormalities are greater than in iron deficiency at the same Hb and nucleated red cells are usually present, whereas they are not a feature of iron deficiency. If the patient is being transfused regularly, normal donor cells will also be present, producing a dimorphic blood film (Fig. 5.18).

Anisochromasia (αυισoζ, unequal) and Dimorphic Red Cell Population

A distinction should be made between anisochromasia, in which there is abnormal variability in staining of red cells, and a dimorphic picture, in which there are two distinct populations. Anisochromasia, in which some but not all of the red cells stain palely, is characteristic of a changing situation. It can occur during the development or resolution of iron deficiency anaemia (Fig. 5.19) or the anaemia of chronic disease. In thalassaemia trait, in contrast, anisochromasia is much less common. A dimorphic blood film can be seen in several circumstances. It can occur when an iron deficiency anaemia responds to iron therapy, after the transfusion of normal blood to a patient with a hypochromic anaemia (Fig. 5.19), and in sideroblastic anaemia (Fig. 5.20). In acquired sideroblastic anaemia as a feature of a myelodysplastic syndrome, the two populations of cells are usually hypochromic microcytic and normochromic macrocytic, respectively.

Damage to red cells after formation

Spherocytosis (σϕαιρα, a sphere)

Spherocytes are cells that are more spheroidal (i.e. less disc-like) than normal red cells but maintain a regular outline. Their diameter is less and their thickness is greater than normal. Only in extreme instances are they almost spherical in shape. It is useful to draw a distinction between spherocytes of normal size and microspherocytes; the latter result from red cell fragmentation or from removal of a considerable proportion of the red cell membrane by splenic or other macrophages. Spherocytes may result from genetic defects of the red cell membrane as in hereditary spherocytosis (Fig. 5.21); from the interaction between immunoglobulin- or complement-coated red cells and phagocytic cells, as in delayed transfusion reactions, ABO haemolytic disease of the newborn (Fig. 5.22) and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (Fig. 5.23); and from the action of bacterial toxins (e.g. Clostridium perfringens lecithinase; Fig. 5.24).

Spherocytes usually appear perfectly round in contour in stained films; they have to be carefully distinguished from both irregularly contracted cells and ‘crenated spheres’ or sphero-echinocytes (Fig. 5.25), which are the end result of crenation (see p. 82). Sphero-echinocytes develop as artefacts, especially in blood that has been allowed to stand before films are spread (Fig. 5.26). The blood film of a patient who has been transfused with stored blood may show a proportion of sphero-echinocytes (Fig. 5.27).

Irregularly Contracted Red Cells

There are a number of causes of irregularly contracted cells. In drug- or chemical-induced haemolytic anaemias, a proportion of the red cells are smaller than normal and unusually densely stained (i.e. they appear contracted) and their margins are slightly or moderately irregular and may be partly concave (Fig. 5.28). These may be cells from which Heinz bodies have been extracted by the spleen. Similar cells may be seen in films of some unstable haemoglobinopathies before splenectomy (e.g. that caused by the presence of Hb Köln or Hb St Mary’s; Fig. 5.29) and in haemoglobin E homozygosity (Fig. 5.30) and, to a lesser extent, haemoglobin E heterozygosity. Heinz bodies are not normally visible in Romanowsky-stained blood films, but they may be seen in such films as pale pink–staining bodies at the cell margin or even protruding from the erythrocytes in severe unstable haemoglobin haemolytic anaemias after splenectomy and in acute oxidant-induced haemolytic anaemia, including that occurring in deficiency of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. An extreme degree of irregular contraction is characteristic of severe favism or any other very acute haemolytic episode in individuals who are glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficient. It is typical to see cells in which the haemoglobin appears to have contracted away from the cell membrane, an appearance sometimes referred to as a hemi-ghost (Fig. 5.31

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

ρ, over)

ρ, over)