In practice, patients with benign liver tumors typically present in three broad clinical scenarios: (1) a liver tumor incidentally discovered in an asymptomatic patient, (2) a liver tumor identified during surveillance in a patient with a history of malignancy or chronic liver disease, and (3) a liver tumor discovered during evaluation of upper abdominal symptoms. Advances in cross-sectional imaging coupled with increased utilization have led to an increase in the incidental identification and diagnosis of benign liver tumors. The vast majority of incidentally discovered liver tumors are benign, do not cause symptoms, and do not require resection. When symptoms are present, typically they are vague, ill-defined complaints presumably related to stretching of Glisson’s capsule or associated with a mass effect from compression of adjacent structures. Hence, since the majority of these benign liver masses are asymptomatic and some patients have unrelated, vague upper abdominal symptoms, the onus is on the clinician to ascertain causality as precisely as possible to determine the need for surveillance or a treatment strategy and to avoid unnecessary treatment. In this chapter, the clinical features and treatment options for the three most common benign solid liver tumors are discussed: hepatic hemangioma, focal nodular hyperplasia, and hepatocellular adenoma (HA). Other rare, unusual benign liver tumors are reviewed in brief. Cystic tumors are discussed elsewhere. Table 136-1 illustrates the broad differential diagnosis of benign liver tumors. With the exception of HA, the majority of benign liver tumors are not associated with malignancy and do not require resection if the diagnosis can be established without an operation. Minimally invasive operative techniques should not expand the indication for resection of benign liver tumors.

Differential Diagnosis of Benign Liver Tumors

| Cystic | Simple cyst |

| Cystadenoma | |

| Ciliated hepatic foregut cyst | |

| Polycystic liver disease | |

| Infectious/Inflammatory | Pyogenic abscess |

| Amebic abscess | |

| Echinococcal disease | |

| Sarcoid | |

| Solid | Hemangioma |

| Focal nodular hyperplasia | |

| Hepatocellular adenoma | |

| Bile duct adenoma | |

| Bile duct hamartoma (von Meyenburg complex) | |

| Lipoma | |

| Myelolipoma and angiomyolipoma | |

| Regenerative and dysplastic nodules | |

| Pseudotumors | Focal fatty infiltration |

| Focal fatty sparing | |

| Peliosis hepatis | |

| Flow abnormalities | |

| Inflammatory pseudotumor |

Hemangiomata are the most common benign liver tumor with overall prevalence between 2% and 20% in the general population.1 Most hepatic hemangiomata are discovered in middle-aged patients with a 5:1 predominance in women. Approximately one-third of the patients have multiple hemangiomata. The majority of hemangiomata are less than 5 cm; however, these lesions can become quite large. “Giant hemangioma” is a term used to describe size greater than 4 cm, although many centers emphasize the appropriateness of nonoperative therapy even for significantly larger lesions.2,3 As no clear correlation exists between hemangioma size, symptoms, and the need for therapeutic intervention, the term “giant” is of limited clinical utility.

The pathogenesis of hemangiomata is not well understood. Structurally, these tumors are mesenchymal cavernous vascular abnormalities with blood-filled fibrous sinusoidal spaces lined by flattened endothelium. Enlargement of hemangiomata is presumed to result from ectasia of existing vessels rather than angiogenesis. Hence, tumor growth is marked by pushing borders rather than infiltration. As it expands, a pseudocapsule forms around the hemangioma. Thus, the surrounding parenchyma and vasculobiliary structures become displaced and compressed rather than invaded. Enlargement can be associated with internal fibrosis, hemorrhage, thrombosis, and calcification with resultant heterogeneity in imaging findings. Some of these changes may lead to symptoms. High-estrogen states such as puberty, pregnancy, or estrogen replacement therapy have been associated with observed accelerated growth; however, a causal relationship has never been established.4 Chronic liver disease and cirrhosis frequently lead to a decrease in hemangioma size as the sponge-like fibrous sinusoidal spaces collapse from progressive fibrosis.

Spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage of hemangiomata, while frequently discussed, are exceedingly rare. Less than 50 cases have been reported over the last century; a majority of the published literature is of historic interest.5 Hemangiomata are frequently identified during imaging for unrelated reasons. The clinical challenge is determining the causality between patient symptoms (if any) and the presence of a hemangioma.

When present, symptoms most commonly associated with hemangiomata are abdominal pain, discomfort, and abdominal fullness.6,7 Typically, symptoms are nonspecific and vague. Consequently, there is considerable overlap with other causes of abdominal symptoms, which are much more common than symptomatic hemangiomata. Alternatively, some patients experience symptoms from mass effect such as early satiety and nausea. On occasion, patients with a hemangioma may present with severe, acute right upper quadrant abdominal pain. This can occur from thrombosis within a portion of the tumor and is thought to lead to stretching and/or inflammation of Glisson’s capsule. While this pain resolves with time as the inflammatory process recedes, the resolution of symptoms can take several weeks. Rare case reports describe significant mass effects from very large hemangiomata, including clinical biliary obstruction and hepatic vein compression leading to jaundice or Budd–Chiari syndrome. Hemangioma thrombocytopenia syndrome (Kasabach–Merritt syndrome), which is quite rare, has been described in adults with hepatic hemangioma.8

Hemangiomata are soft sponge–like tumors that compress with external pressure. A physiological explanation for the clinical symptoms associated with hemangiomata remains elusive. One hypothesis suggests that pain results from the distention of Glisson’s capsule. As such, patients with a hemangioma abutting and stretching the liver capsule might present with abdominal complaints. However, most patients with a hemangioma causing capsular abutment or stretch are asymptomatic (Fig. 136-1A, B). Curiously, patients with similar capsular distention from a malignancy typically do not have pain. The capsular stretch concept also does not explain symptoms reported by patients with intraparenchymal hemangiomata. In patients with abdominal fullness, nausea, and vomiting, it is easier to understand symptoms associated with large hemangiomata when there is radiographic abutment or compression of adjacent organs. Again, it is unclear why these symptoms are absent in patients with intrahepatic malignancies having a similar radiographic appearance with adjacent organ compression. Overall, four principles should be considered: (1) the majority of patients with hepatic hemangiomata (including “giant hemangioma”) do not have symptoms and do not need treatment; (2) there is a broad differential diagnosis of other potential etiologies (gallstone disease, peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux, functional bowel disease, etc.) that cause similar symptoms and are more common than symptomatic hemangiomata; (3) minimally invasive approaches should not expand the indications for treatment; and (4) the treatment of hepatic hemangiomata does not address the underlying symptoms in approximately 50% of patients.2

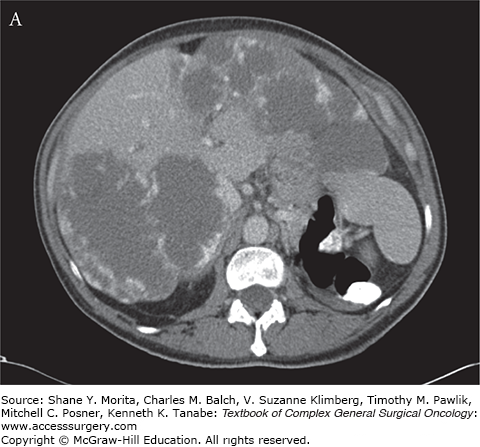

FIGURE 136-1

Hepatic hemangioma characteristics. A. CT of an asymptomatic patient with bilobar giant hemangiomata demonstrating peripheral nodular enhancement without complete opacification during the venous phase. B. Typical discontinuous nodular enhancement during the gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI in an asymptomatic patient with giant hemangioma compressing the gallbladder fossa.

Noninvasive imaging is diagnostic for hepatic hemangioma in nearly all cases in patients without a history of chronic liver disease or malignancy. In this population, ultrasound (US) is highly accurate, primarily for smaller (less than 3 cm) hemangiomata.9 Characteristic sonographic features include a well-defined, homogeneously hyperechoic liver mass with no posterior shadowing. Alternatively, a hemangioma can appear as a hypoechoic, well-defined mass in the context of a fatty liver. Color Doppler is not helpful in improving the accuracy of US for this diagnosis.10 Therefore, in a patient with a small liver lesion exhibiting these characteristics and no history or current evidence of malignancy or chronic liver disease, no further diagnostic study or follow-up is necessary.11 While highly specific for smaller lesions, atypical US features are common in larger hemangiomata. When atypical sonographic features are identified or there is uncertainty from the US findings, further radiographic evaluation is warranted.

The majority of hemangiomata are definitively diagnosed by cross-sectional imaging (computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)).12,13 The classic triple-phase CT findings are highly reliable for the diagnosis of hemangioma. An accurate diagnosis by CT requires strict fulfillment of published criteria: (1) a well-defined, relatively hypodense lesion compared to the surrounding hepatic parenchyma during the precontrast phase; (2) early, peripheral, globular (nodular) enhancement of the lesion during the dynamic arterial phase; (3) centripetal enhancement of the lesion that progresses to uniform opacification during the venous phase; and (4) complete, isoattenuating opacification on delayed phase images.14 CT imaging characteristics can vary with tumor size, and both small and large lesions can demonstrate atypical enhancement patterns.15 Small lesions frequently enhance too rapidly to meet CT criteria, while the large lesions demonstrate variable opacification (Fig. 136-1A) dependent on the size of the lesion and extent of internal fibrosis or thrombosis. However, beware of the diagnosis of “atypical hemangioma” as this can be a masquerade for other lesions, including malignant lesions.15 If US or CT is diagnostic, further imaging is not necessary; however, when US or CT demonstrates atypical features, MRI can help secure the diagnosis.

At many institutions, MRI has become the imaging study of choice for focal liver lesions.16,17 It has become the gold standard for the diagnosis of hepatic hemangiomata as it performs better than other imaging modalities.18 A hemangioma is defined as a well-circumscribed lesion with the following characteristics: (1) hypointense relative to normal liver parenchyma on T1-weighted images; (2) hyperintense relative to normal liver parenchyma on T2-weighted images, but typically less than a hepatic cyst; (3) hyperintense relative to normal liver parenchyma on diffusion-weighted imaging secondary to T2 shine-through; and (4) peripheral, globular (nodular), discontinuous enhancement with delayed centripetal filling on gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images (Fig. 136-1B). The accuracy of MRI for the diagnosis of hepatic hemangioma is very high with sensitivity >90% and specificity approaching 100%.19 Very rarely, the diagnosis cannot be confirmed by imaging. In these exceptional cases percutaneous biopsy is demonstrated to be safe and effective.20,21

The use of technetium-99m pertechnetate labeled red blood cell study and angiography for the diagnosis of hemangiomata primarily is of historical interest.

While the natural history of hepatic hemangiomata is incompletely understood, numerous publications provide insight into their behavior. This, then, informs the long-term management of hemangiomata. Several studies reported no change in approximately 80% of hemangiomata.22,23 A few published case reports show significant growth over periods of up to 11 years.24,25 Others show the need for active treatment in a small minority of patients.26 The risk of much discussed, but rare, complications such as rupture or hemorrhage is low.

Regardless of size, treatment is not indicated for asymptomatic hemangiomata.2,3 Patients with diagnostic imaging establishing the diagnosis of a hemangioma should be reassured. There is no need for cessation of oral contraceptives (OCs), changes to fertility plans, or modification of activity level. Surveillance is not indicated. While some authors have advocated for “observation” and serial imaging based on the rare possibility that the hemangioma might grow, this is unnecessary since treatment is symptom driven. Treatment is not indicated based solely on the size of the hemangioma, its growth, or prophylaxis to prevent bleeding, rupture, or injury. Expansion of minimally invasive techniques (including laparoscopy and robotics) should not influence indications for resection.

With proper caution and judicious patient selection, operative therapy is uncommon.27 Operative therapy is limited to patients with (1) severe intractable symptoms in the absence of another etiology, (2) intraparenchymal or intraperitoneal hemorrhage (rarely associated with hemangioma thrombocytopenia syndrome), (3) biliary or hepatic venous obstruction, or (4) diagnostic uncertainty and inability to exclude malignancy. The first three indications are frequently associated with massive lesions.

Operative approaches for hemangiomata include enucleation or parenchymal resection. The majority of hemangiomata are surrounded by a pseudocapsule with compression of the surrounding parenchyma without invasion. Thus, enucleation of the hemangioma is an excellent option. To begin, Glisson’s capsule is divided to the level of the pseudocapsule. A dissection plane is developed between the pseudocapsule of the hemangioma and the compressed parenchyma, allowing enucleation. Enucleation reportedly has fewer complications including less blood loss and bile leaks, while preserving hepatic parenchyma.28 If the hemangioma is not abutting Glisson’s capsule or the margins of enucleation cannot be safely defined, a liver resection (nonanatomic or anatomic) can be performed. Since most of the hemangiomata requiring resection are massive, the basic principles of safe hepatic transection including low central venous pressure anesthesia, inflow control, meticulous hemostasis, and bile stasis are paramount. Cell salvage can be safely used and allows autotransfusion of shed blood. Temporary occlusion (enucleation) or ipsilateral ligation (lobectomy) of the hepatic artery will facilitate decompression of the hemangioma and make resection easier.

The exceptional patient with a ruptured hemangioma should be managed with angiography and embolization. Once the bleeding is controlled and the patient is stable, enucleation or resection is appropriate. Very rare cases of hepatic venous outflow obstruction or hemangioma thrombocytopenia syndrome merit consideration for liver transplantation.

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) is the most common, nonhemangioma, benign liver tumor. Its overall prevalence approximates 1% in the general population.29 Similar to hemangioma, most FNHs are identified in patients between 30 and 50 years of age with a 9:1 predominance in women. Up to 20% of the patients have multiple FNHs. The majority (65%) of lesions are less than 5 cm in size, with a median size of 3 cm.30

While the exact pathophysiology and development of FNH is not well understood, the lesion is thought to represent a hyperplastic hepatocyte response to increased blood flow within a developmental arterial malformation.31 Hence, the lesion is not a true neoplasm and the chance of malignant transformation is null. FNHs are well circumscribed, but not encapsulated, lesions. Occasionally there is a large anomalous feeding artery supplying the FNHs, which is visible on imaging and evident during gross pathologic evaluation. Structural components of FNH include benign-appearing hyperplastic hepatocytes arranged in nodules with fibrous septa originating from the central scar. Classically, FNHs are described as having a macroscopic central scar, a feature that can be useful to distinguish it on imaging. However, this feature is present in only about 50% of patients.30 Other vascular abnormalities including arteriovenous malformations, telangiectasias, and anomalous venous drainage patterns have been described in patients with multiple FNHs.

As a benign process without malignant potential, FNHs do not pose any known risk to the patient. While involution after menopause has been described, there is no known association between high estrogen states and tumor growth.32 As such, OCs can be continued safely in women with FNHs.33 Similar to hemangiomata, the majority of FNHs are asymptomatic. Analogous to patients with hemangiomata, when an FNH abuts and/or stretches Glisson’s capsule there is the theoretical potential of causing abdominal pain or discomfort. Risk of rupture is negligible and reported cases may represent misdiagnosed cases of ruptured HA.

Clinically, FNH is important as it frequently represents a diagnostic challenge. Despite advances in imaging, diagnostic uncertainty continues to exist between FNHs and other solid hepatic lesions with the result that it affects evaluation and treatment decisions. Radiographic absence of the central scar in approximately 50% of cases contributes to this dilemma. Historically, variants such as atypical telangiectatic FNHs have been described, representing approximately 15% of FNHs, further contributing to the diagnostic uncertainty.30 Recently, molecular analysis of the telangiectatic variant of FNH identified a molecular profile that is similar to HA. As such, these lesions have been recategorized as telangiectatic (inflammatory) adenoma and not FNH.34,35 Thus, any “atypical FNH” should be carefully evaluated to exclude HA.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree