Nonproliferative lesions

Cysts

Mild hyperplasia of the usual type

Epithelial-related calcifications

Fibroadenoma

Papillary apocrine change

Proliferative lesions without atypia

Sclerosing adenosis

Radial and complex sclerosing lesions

Moderate and florid hyperplasia of the usual type

Intraductal papillomas

Atypical proliferative lesions

Atypical ductal hyperplasia

Atypical lobular hyperplasia

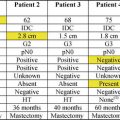

Table 34.2

Clinical classification of benign breast diseases

Physiologic swelling and tenderness |

Nodularity |

Breast pain |

Palpable lumps |

Nipple discharge |

Breast infections and inflammation |

Most commonly encountered lesions in this segment are (a) lactation-related inflammation (acute mastitis), (b) non-puerperal periareolar inflammatory entities (periductal mastitis, Zuska’s disease, and mammary duct ectasia), (c) fat necrosis, (d) sclerosing lymphocytic lobulitis, and (e) granulomatous mastitis. Those entities will be discussed below.

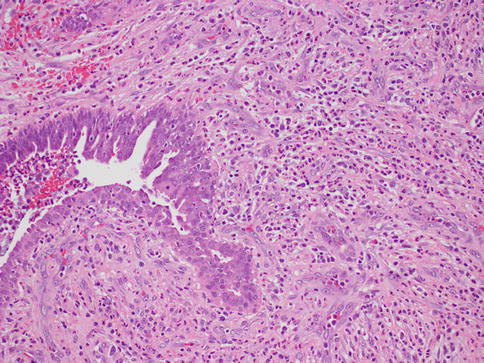

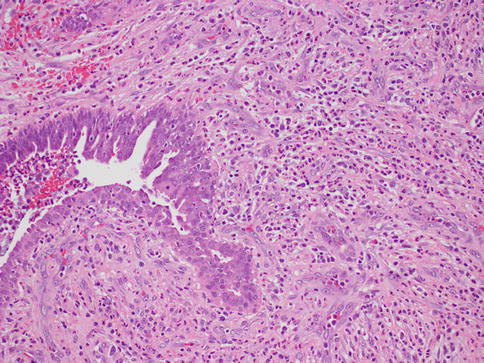

Lactation-Related Inflammation (Acute Mastitis)

Lactation-related inflammation is frequently seen during the first few months of breastfeeding. This is in contrast with inflammatory breast carcinoma, which is usually not associated with pregnancy [2]. The abscess appears as a red mass filled with pus and sometimes can mimic cancer. Biopsy procedures are rarely performed for this disorder, since it is usually managed by nonoperative means [4]. Synonyms are puerperal or acute mastitis, most usually presenting with the classical signs and symptoms of inflammation, such as localized pain, erythema, and associated fevers (Fig. 34.1). This is an inflammation of the breast stroma usually composed of neutrophils and plasma cells, which can lead to abscess formation and septicemia if left untreated [5]. Staphylococcus aureus is the most commonly identified infectious agent followed by Staphylococcus epidermidis and streptococci. Special stains can sometimes highlight the offending microorganism. It is thought that sleep deprivation, stress, and improper nursing techniques result in milk stasis and cracks of the nipple that lead to inflammation and infection [6]. Early diagnosis and treatment with antibiotics can lower the incidence of abscess formation. One should show due diligence in avoiding the use of antibiotics such as tetracycline that pass into breast milk and have harmful effects on the infant. Once an abscess is formed, aspiration or incision and drainage should be performed. Despite antibiotic therapy and drainage, if there is no response or if solid areas are identified, a tissue biopsy should be obtained to rule out the possibility of carcinoma.

Fig. 34.1

Acute mastitis. Hematoxylin and eosin stain at 200× magnification

Non-puerperal Periareolar Inflammatory Entities (Periductal Mastitis, Zuska’s Disease, and Mammary Duct Ectasia)

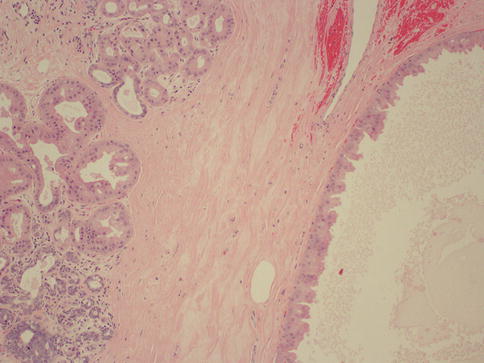

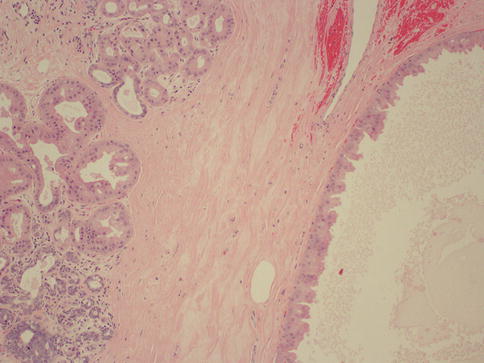

The main difference between periductal mastitis and Zuska’s disease or recurring subareolar abscess is that the latter occurs due to squamous metaplasia of the lactiferous ducts of the nipple, with secondary keratin plug formation that obstructs the proximal duct causing dilation and infection [5] (Figs. 34.2 and 34.3). This leads to abscess and fistula formation that drains at the margin of the areola [7]. Therefore Zuska’s disease is also called SMOLDering (squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts) and can present with an inflamed and indurated nipple, nipple retraction, and painful nodules thus potentially mimicking cancer. Abscess drainage and excision of the affected ducts and fistula is the preferred treatment. In one series of 67 cases, half of the patients were successfully managed medically and the other half required surgical intervention [8]. In the same study, it was shown that radial elliptical incision with primary closure gave excellent long-term results. However, another study that looked at 24 women with a subareolar abscess suggests that the abscess together with the plugged duct has to be excised in order to prevent a recurrence [9]. The microbiologic studies performed on the material obtained from the lesions usually identify staphylococcus as the main infectious agent. Recurrent abscesses usually yield a mixed flora.

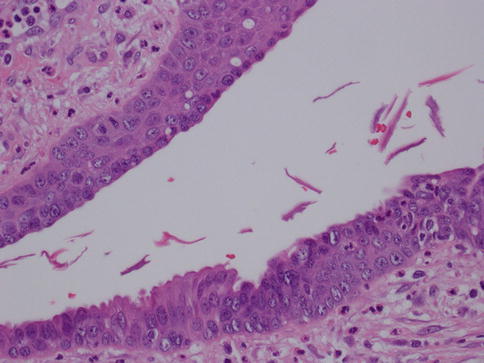

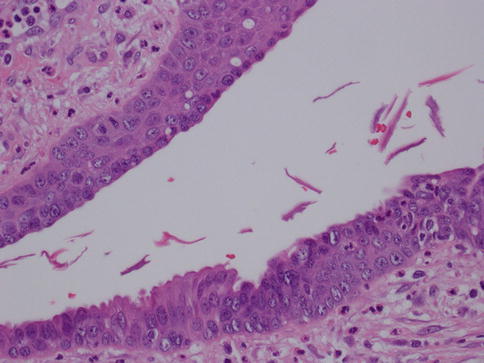

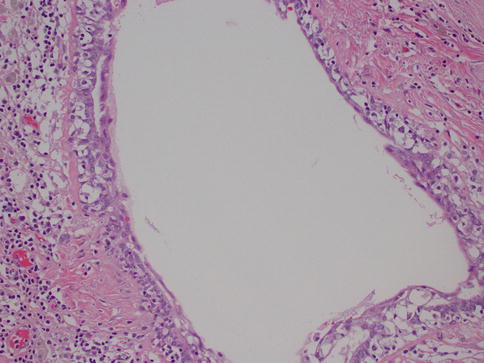

Fig. 34.2

Recurring subareolar abscess: squamous metaplasia. Hematoxylin and eosin stain at 400× magnification

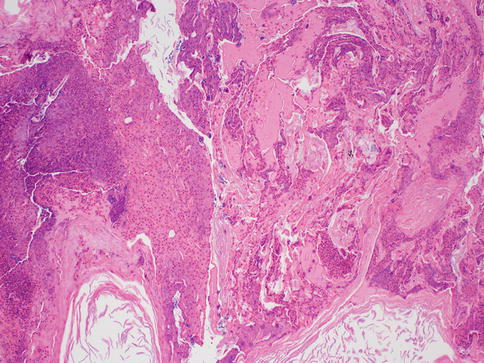

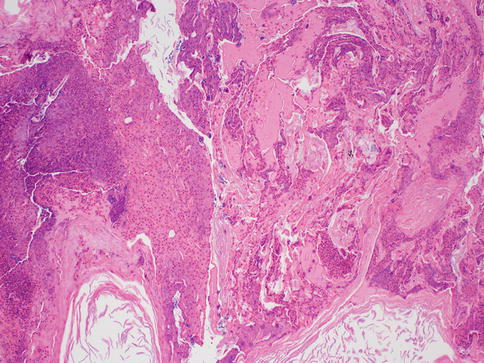

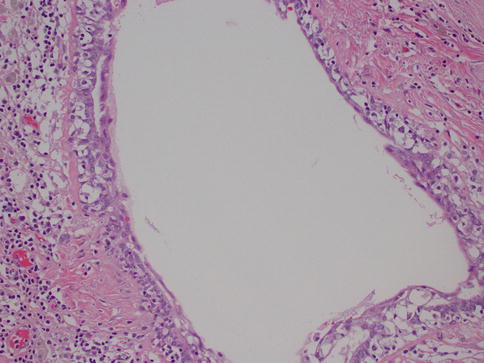

Fig. 34.3

Recurring subareolar abscess: keratin plug with secondary infection. Hematoxylin and eosin stain at 100× magnification

In a series of 60 patients suffering from recurrent subareolar breast abscess, heavy smoking was found at an unusually high frequency compared to a control group. The authors of the study postulated that cigarette smoking could have either a direct toxic effect on the retroareolar lactiferous ducts or an indirect effect via hormonal stimulation of the breast secretion [10]. Periductal mastitis on the other hand does not show squamous metaplasia, and the ducts are not dilated. It can occur centrally (periareolar) or peripherally. Periductal mastitis affects younger patients and should not be confused with mammary duct ectasia, which is a condition of the perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Mammary duct ectasia characteristically shows dilation of the major ducts of the nipple with periductal fibrosis and inflammation (Fig. 34.4). The ducts may contain eosinophilic, granular, or inspissated material and sometimes may become calcified. On gross examination, the inspissated material may mimic comedo necrosis that is associated with ductal carcinoma in situ. Some suggest that it is also related to smoking [11]. The disease usually affects the middle aged to older women and is usually asymptomatic. Occasionally, patients may present with nipple inversion, retraction, discharge, or a subareolar mass that may mimic a breast cancer [4]. Therefore, some patients with duct ectasia are biopsied to exclude malignancy; otherwise, most can be safely managed with mainly conservative measures [5]. Recurrence is uncommon.

Fig. 34.4

Duct ectasia. Hematoxylin and eosin stain at 200× magnification

Fat Necrosis

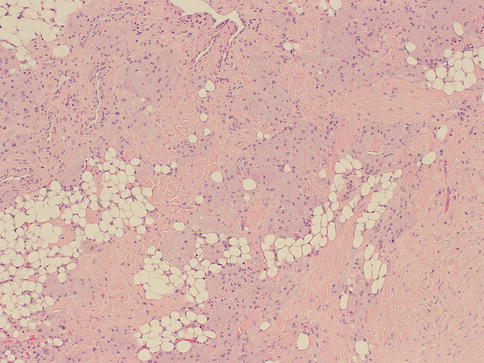

This is another entity that can be clinically confused with cancer, as it may present as an ill-defined, spiculated mass with associated skin retraction. Small areas of fat necrosis are probably not uncommon, but clinically significant lesions are likely due to some sort of trauma, surgical procedure, biopsy, and radiation present in up to 50 % of patients; however the exact etiology is not always identified [12]. The lesion can also be associated with an adjacent malignancy [5]. Grossly, it may appear as a firm, ill-defined mass. Microscopically, the diagnosis is usually straightforward and is characterized by cystic spaces surrounded by lipid-laden histiocytes and foreign body-type giant cells (Fig. 34.5). Hemorrhage, a variable inflammatory infiltrate, and fibrosis can also be identified. When the lesion is fully evolved, it may have the appearance of a cystic cavity with calcified walls sometimes referred to as membranous fat necrosis [13].

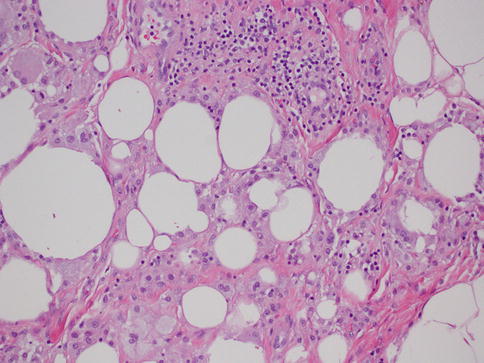

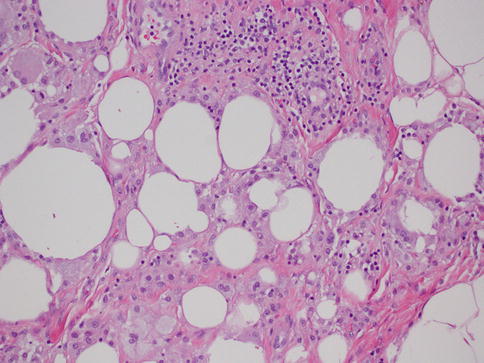

Fig. 34.5

Fat necrosis. Hematoxylin and eosin stain at 200× magnification

Sclerosing Lymphocytic Lobulitis

This is a disorder usually occurring in patients with type 1, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. It can also be seen in nondiabetic patients that are affected by other autoimmune disorders such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis [14]. It is characterized by painless, immobile, discrete masses that are clinically suspicious for carcinoma. The lesions are usually bilateral but might also occur as a single mass. Radiologic findings can also be suspicious and usually require a biopsy to rule out a malignant proliferation. The majority of diabetic mastopathy lesions occur in the upper outer quadrant and are irregularly demarcated from the surrounding breast tissue.

Histologically, one usually finds a keloid-like fibrotic stroma; periductal, lobular, or perivascular lymphocytic infiltration by B cells; lobular atrophy; and fibroblasts embedded in fibrous stroma. Some point out that those findings are not specific as they may also be identified in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 and nondiabetic patients [15]. It is postulated that this represents an immune reaction to hyperglycemia on connective tissue. Others suggest vascular changes as possible factors in the pathogenesis of diabetic mastopathy [16]. Microscopically sclerosing lymphocytic lobulitis shows small lymphocytes extending into epithelial cells, thus potentially mimicking a primary low-grade B cell lymphoma of the breast. Follow-up of patients with diabetic mastopathy is generally recommended.

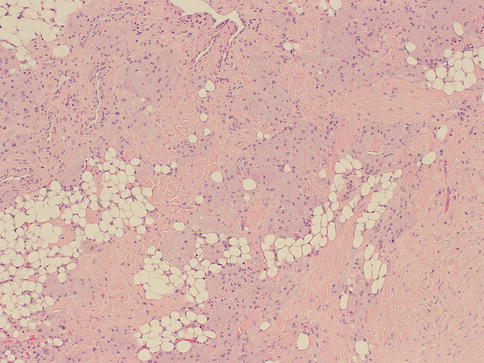

Granulomatous Mastitis

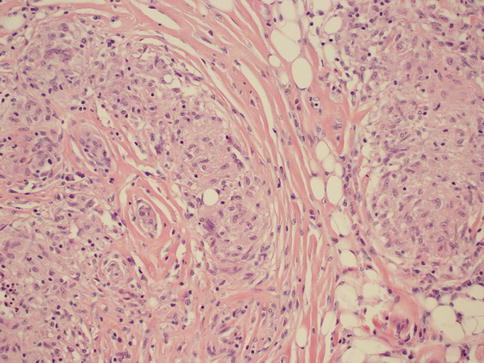

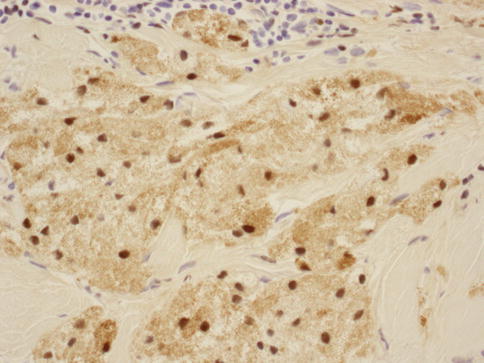

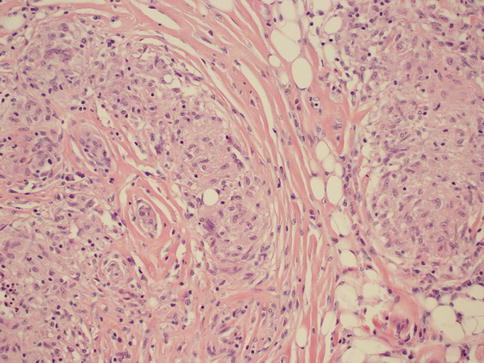

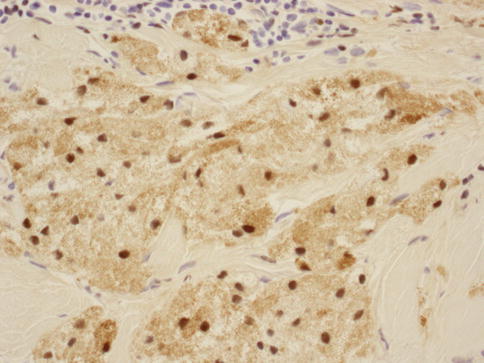

As in other parts of the body, granulomatous inflammation (Fig. 34.6) of the breast can be infectious, idiopathic, due to foreign material or secondary to a systemic autoimmune disease such as sarcoidosis. The latter rarely involves the breast, but it can simulate a neoplasm [17]. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and characterized by non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis is an entity without an identifiable cause, thus also a diagnosis of exclusion. It may present as a mass simulating carcinoma, and it usually occurs in young women, often related to a recent pregnancy [18]. The management of this entity requires surgical excision, but sometimes it responds to corticosteroid therapy [4]. Management can be problematic, and despite treatment, recurrence and complications such as abscess and fistula formation are frequent [19]. The treatment sometimes spans over several years. Microscopically there are three neoplastic conditions in the differential diagnosis: histiocytic subtype of lobular carcinoma, carcinoma with osteoclastic giant cells, and granular cell tumor. In cases with abundant histiocytic cells, the inflammation can be confused with a rare variant of invasive lobular carcinoma called histiocytic type, where the neoplastic cells have ample cytoplasm and are disguised as histiocytes. In difficult cases immunohistochemical stains for keratin would confirm the diagnosis of carcinoma. The second tumor is invasive carcinoma with osteoclastic giant cells. In this condition malignant cells are accompanied by numerous reactive giant cells that are CD68 positive pointing to their histiocytic nature. Careful analysis of the surrounding carcinomatous cells should help in arriving at correct diagnosis. Granular cell tumor is another entity that might mimic an inflammatory condition composed of histiocytes. It is a rare neoplasm that usually occurs in other parts of the body, such as the head and neck, oral cavity, and digestive system [20]. It can also involve the breast in approximately 5 % of cases. This is a benign tumor that clinically may show fixation to the pectoral fascia, skin retraction, and ulceration, thus mimicking an invasive carcinoma. It may also occur in the male breast [21]. They are usually small lesions, measuring less than 3 cm, composed of polygonal cells with granular cytoplasm mimicking histiocytes (Fig. 34.7). They express the S100 protein and this is very useful in the confirmation of the diagnosis (Fig. 34.8). The tumor is believed to arise from peripheral nerve sheet cells, i.e., Schwann cells. Rarely, the tumors can be malignant, with the most useful characteristics of malignancy being large size (>5 cm), pleomorphic cells, prominent nucleoli, increased mitotic activity, necrosis, and local recurrence. Both benign and malignant tumors are treated with wide surgical excision. Incomplete excision may result in recurrence. Adjuvant treatment is only reserved for malignant tumors.

Fig. 34.6

Non-necrotizing granulomatous mastitis. Hematoxylin and eosin stain at 200× magnification

Fig. 34.7

Granular cell tumor. Hematoxylin and eosin stain at 40× magnification

Fig. 34.8

Granular cell tumor: S100 stain at 400× magnification

Fibrocystic Changes (FCC) and Columnar Cell Changes (CCC)

Previously referred to as fibrocystic “disease” of the breast, the term “disease” has been dropped in favor of “changes.” This is due to its very high prevalence and because it caused confusion between normal, physiologic changes and pathological ones [22]. Histologically, fibrocystic change can be identified in up to 90 % of all breast tissue examined in women. The most common presenting symptoms are breast pain and palpable nodules or lumps in the breast. It has been noted in a retrospective cohort study that only 6 % of patients between 40 and 70 years of age presenting with breast symptoms had cancer [23]. Cysts are the main component of fibrocystic changes and are characterized by fluid-filled structures that are mostly small and non-palpable, but approximately 20–25 % of them are large enough to present as masses [5, 24]. Mammography and physical examination are not reliable and cannot truly distinguish cysts from solid masses [25]. The utility of ultrasound can help to further define an abnormality identified on mammogram. Simple cysts are usually devoid of a lining or have a flat epithelium that sometimes may show apocrine metaplasia. Complex cysts have internal thin septations, thickened or irregular wall, and absent posterior acoustic enhancement on ultrasound. The malignancy rate in patients with complex cysts is very low, 0.3 % in one study, lower than that of lesions classified as probably benign [26]. If there is concern that the cyst is other than a simple cyst, possibly with internal wall thickening or complex septations, consideration should be given to further evaluation and possible biopsy of these areas in order to exclude a malignancy.

Besides cysts, FCC also comprises other lesions such as apocrine metaplasia (Fig. 34.9), epithelial hyperplasia both atypical and non-atypical, adenosis, radial scar, and papilloma. The most useful way to classify FCC is to divide it into three groups according to their risk of developing breast cancer: nonproliferative lesions (cysts, apocrine metaplasia, mild epithelial hyperplasia, non-sclerosing adenosis), proliferative lesions without atypia (moderate to florid epithelial hyperplasia, sclerosing adenosis, radial scar, papilloma, and papillomatosis), and proliferative lesions with atypia (atypical ductal hyperplasia and atypical lobular hyperplasia) [5] (Table 34.3). Relative to general population, women with nonproliferative lesions have no increased risk for developing breast cancer. On the other hand patients with non-atypical proliferative and atypical proliferative lesions have relative risks ranging from 1.3 to 1.9 and 3.9 to 13, respectively [27–30].

Fig. 34.9

Fibrocystic changes. Hematoxylin and eosin stain at 100× magnification

Table 34.3

Classification of fibrocystic changes

Nonproliferative lesions | Proliferative lesions without atypia | Proliferative lesions with atypia |

|---|---|---|

Cysts | Moderate to florid epithelial hyperplasia | Atypical ductal hyperplasia |

Apocrine metaplasia | Sclerosing adenosis | Atypical lobular hyperplasia |

Mild epithelial hyperplasia | Radial scar | |

Non-sclerosing adenosis | Papilloma and papillomatosis |

Adenosis and Microglandular Adenosis

Adenosis is defined as a glandular proliferation of the lobular units, with two subtypes that merit mentioning: sclerosing adenosis and microglandular adenosis. Sclerosing adenosis is a disordered proliferation of acini, myoepithelial cells and stromal elements that can be confused for invasive carcinoma both microscopically and grossly [5]. It can present as a mass or a radiologic abnormality such as an asymmetric opacity, cluster of microcalcifications, mass-like lesion, and architectural distortion [31]. In difficult lesions posing a diagnostic challenge, myoepithelial markers can be performed to rule out carcinoma.

On the other hand, microglandular adenosis is characterized by a proliferation of uniform small round glands haphazardly distributed within the breast parenchyma. The most important aspect of this lesion is that it lacks a myoepithelial layer; thus it can be easily confused with carcinoma. The presence of basal lamina encircling glandular structures, which can be confirmed by immunohistochemical stains, and overall round, rather than angulated, morphology of the glands are features that can be used in ruling out a malignant process. There is some evidence that microglandular adenosis can potentially progress to carcinoma, and it can recur if incompletely excised. Occasionally, microglandular adenosis presents as a palpable mass and may be associated with both in situ and invasive carcinoma [32].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree