Major Concepts

Diseases

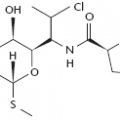

Four Bartonella species cause human disease. These are B. bacilliformis, B. henselae, B. quintana, and B. elizabethae. These small gram-negative bacilli belong to the α-2 subgroup of Proteobacteria. They produce bartonellosis (Oroya fever and verruga peruana), cat-scratch disease, and trench fever in immunocompetent persons and cause bacillary angiomatosis, bacillary peliosis hepatis, and endocarditis in immunocompromised individuals, especially those who are HIV-positive. Several of these conditions induce fever; others cause skin lesions or vascular endothelial proliferation. Oroya fever, with its severe hemolytic anemia, has a high mortality rate if untreated, and the accompanying endocarditis often necessitates heart valve replacement.

Transmission

Arthropods play important roles in the transmission to humans of several Bartonella species. The vectors for B. bacilliformis are members of a group of sand flies with a very restricted geographical range. The human body louse is the vector for B. quintana. The cat flea transmits B. henselae between cats; the cats subsequently infect humans by scratching, biting, or licking. Surveillance studies show that high numbers of cats either are currently infected or have previously been infected with B. henselae. Some areas of the world also have significant proportions of the arthropod vector population infected with Bartonella bacteria. Methods that decrease human exposure to the arthropod vectors help control diseases associated by Bartonella and other bacterial species.

Immune Response

The immune system plays an important protective role in host defense against Bartonella-induced diseases, involving both humoral (IgG1 and IgA) and cell-mediated (Th1 T helper cells and interferon-γ) immunity. Immunosuppressed individuals develop more severe pathology than those with intact defense mechanisms, particularly HIV-positive persons who have defective CD4+ T helper cell responses.

Protection

The mild or self-limiting illnesses produced by Bartonella infection, such as cat-scratch disease, are often not treated with drugs. Other diseases, such as Oroya fever, bacillary angiomatosis, and bacillary peliosis hepatis, are treated with antibiotics, which also kill microbes that cause problematic secondary infections. Other treatment options, such as blood transfusion, draining or excising lesions, or replacing damaged heart valves, may also be employed.

A wide spectrum of diseases results from infection with the four Bartonella bacterial species that infect humans. Although some of these diseases have been known since the early 1900s, they are increasing in incidence and expanding their range in human hosts. The most recently described illnesses associated with Bartonella infection were identified in 1987 and 1993. They may lead to serious illness in immunocompromised persons, especially those who are HIV-positive. The AIDS pandemic has contributed to the impact of these bacteria on the human race. Bartonella infection results in bartonellosis, cat-scratch disease, trench fever, bacillary angiomatosis, bacillary peliosis hepatis, and endocarditis.

Bartonellosis is a potentially severe disease resulting from infection with a small bacterium from the Bartonella genus that is transmitted by sand flies. These insect vectors have a very restricted range in the Andes mountain region; accordingly, bartonellosis is confined to a small area. The disease consists of two stages that were originally believed to be distinct illnesses. The first stage is characterized by fever and hemolytic anemia, which may be fatal. The second stage is a mild cutaneous infection. Cat-scratch disease results from infection by another Bartonella species. It is widespread and affects over 22,000 persons annually, costing over $12 million in the United States alone. It is a mild infection that causes enlarged lymph nodes that exude pus. Trench fever is also caused by a Bartonella bacterium. It is found among individuals living in crowded conditions with poor hygiene. This illness is characterized by fever, headache, and soreness and is usually not fatal but may be more serious among people with AIDS, the homeless, and alcoholics. Bacillary angiomatosis may develop following Bartonella infection of immunocompromised individuals, especially those who are HIV-positive.

Bartonellosis (also known as Carrión’s disease) was so designated in honor of Daniel Carrión, a Peruvian medical student in 1885 who investigated the initial stages of a cutaneous disease known as verruga peruana (Peruvian warts) by injecting himself with material taken from skin infected with Bartonella bacilliformis. Unfortunately, his experiment proved deadly, for he developed Oroya fever, a severe and often lethal hemolytic infection that was not then known to be the first stage of infection with Bartonella. Under appropriate conditions, epidemics of bartonellosis may occur within its narrow geographical confines. The building of the Central Railroad from Lima to Oroya in 1871 occasioned such an outbreak. Some 10,000 Chileans and Chinese with no prior immunity to Bartonella infection were brought into an endemic area of the Peruvian Andes. Approximately 7,000 workers were infected, and the mortality rate approached 40%. Another outbreak occurred in 1938 when B. bacilliformis spread into an adjacent region of Columbia where the population’s immunity to the bacterium was lower; 4,000 persons died in that epidemic. Archaeological evidence of verruga peruana suggests that it has afflicted persons in the Andes of Peru since pre-Columbian days.

The disease that was later designated cat-scratch disease was first recognized in the United States in the 1950 by Lee Foshay while he was studying tularemia. At approximately the same time, Robert Debré linked the occurrence of suppurative (pus-exuding) adenitis in children with multiple scratches from cats. He then studied ill persons who produced positive skin tests (Type IV hypersensitivity reaction) to Foshay’s antigen, leading to the clinical description of the illness. The causative agent was first visualized in lymph node samples in 1983 and identified in 1993.

Trench fever caused epidemics involving tens of thousands of troops and prisoners of war in Europe during World War I and again during World War II as a result of crowded, unsanitary living conditions that favor human infestation by lice, the disease vectors. Though not fatal, trench fever nevertheless led to prolonged periods of disability resulting from relapsing episodes of high fever and severe back and shin pain. Decreased use of trench warfare and improving hygienic conditions greatly reduced disease incidence in later wars. During the 1990s, a form of trench fever appeared among alcoholic, homeless individuals in Seattle, Washington, and also in France.

Bacillary angiomatosis was discovered in 1983, and in 1987 was found to be an opportunistic infection in individuals with AIDS. The lesions closely resembled those occurring during verruga peruana and those seen in Kaposi’s sarcoma (a skin cancer often found in AIDS patients; described in Chapter Seventeen). Kaposi’s sarcoma is caused by a viral infection, whereas the bacillary angiomatosis lesions contain bacilli and respond to antibiotics. The two Bartonella species that induce this condition were isolated from bacillary angiomatosis lesions beginning in 1992. One of these, Bartonella henselae, is also linked to cat-scratch disease; the link between the two diseases was suggested by the finding that individuals who developed bacillary angiomatosis had often done so following contact with cats. When serum samples were analyzed by the CDC, antibodies to B. henselae were found in patients with both conditions. Moreover, when the cats of several persons with bacillary angiomatosis were tested, the animals were found to be bacteremic for B. henselae.

Bartonellosis (Carrión’s Disease)

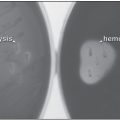

Bartonellosis is restricted to humans and other primates and shows no preference based on age, gender, or race. It manifests initially as a severe acute febrile illness (characterized by fever) with hemolytic anemia that is often fatal (Oroya fever). This stage usually persists for two to three months but may last as long as four months. Some persons may develop flulike prodromal symptoms, such as fever, muscle and joint aches (myalgia and arthralgia), and bone pain. These may be the only evidence of disease in persons with low-level infection. People with a higher level of infection rapidly progress to a toxic state characterized by high fever, chills, headache, and delirium. This is followed by hemolytic anemia resulting from destruction of large numbers of erythrocytes infected by the bacteria. This form of anemia (low number of erythrocytes in the blood) is due to the destruction of red blood cells rather than their loss by hemorrhage or decreased production. The hemolytic anemia induced by Bartonella bacilliformis is extremely rapid, second only to malaria in the rate of drop in hematocrit. Blood smears of infected persons contain large numbers of reticulocytes (immature red blood cells) that are rapidly produced by the bone marrow in an attempt to replace the mature erythrocytes that have been lost. The reticulocytes are polychromatic (stained blue-pink) and are slightly larger than mature cells. Erythrocyte inclusions, such as Howell-Jolly bodies (round remnants of the nucleus), Cabot rings, and basophilic stippling (punctuate, bluish inclusions composed of aggregated ribosomes) may also be present. The anemia leads to the development of jaundice, pallor (pale color), and apathy. Thrombocytopenia (low numbers of platelets) may occur. Nontender lymphadenopathy (swelling of the lymph nodes) and hepatomegaly (enlargement of the liver) may occur, as well as petechiae in some persons. Those who present meningeal symptoms or coma often die. Untreated, the mortality rate for Oroya fever averages 40% (range from 10% to 90%), and many of the fatal cases may be associated with malaria or secondary infection with Salmonella, Mycobacterium, or protozoa species due to immunosuppression following this stage of infection. If treated with antibiotics, mortality drops to 8%.

Table 5.1 Human diseases caused by Bartonella species

| Disease | Causative Agent | Symptoms |

| Bartonellosis (Carrión’s disease) | B. bacilliformis | High fever, chills, headache, jaundice, apathy, delirium, hemolytic anemia, lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, petechiae, meningeal symptoms, coma |

| Cat-scratch disease | B. henselae | Lesions with hyperplasia, granuloma, suppuration with central liquification necrosis, microabscesses, macroabscesses |

| Trench fever | B. quintana | High fever, headache, malaise, severe pain of the back and shins, splenomegaly |

| Bacillary angiomatosis and bacillary peliosis hepatis | B. henselae, B. quintana | Chronic, multifocal vascular cutaneous lesions; erosive vascular proliferative lesions in bone, brain parenchyma, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal, or respiratory systems |

| Endocarditis | B. henselae, B. quintana, B. elizabethae | Inflammation of the heart or the aortic valves, high fever, heart murmur, acute cardiac failure, dyspnea, echocardiographic vegetations, bibasilar lung rales |

If the infected individual survives this stage of the disease, a second, benign cutaneous stage may develop (verruga peruana), preceded by a shifting pain, sometimes severe, in the muscles, bones, and joints that lasts from minutes to several days. The dermal stage is characterized by widely disseminated, hemangiomatous (blood-filled) lesions with diameters of several millimeters or larger and deeper nodular lesions several centimeters in diameter that are found most commonly on the extensor surface of the extremities. The nodules over the joints may become tumorlike with ulcerated surfaces. Histiocytes within the lesions contain Bartonella bacilli. Angioblastic changes (increased growth of blood vessels) are seen upon microscopic examination of the dermis as the endothelial cells divide. Lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils also infiltrate the area. Other symptoms that may be present during this stage of infection include fever, malaise, and anemia, which are less severe than those occurring in Oroya fever. Verruga peruana may reflect the development of an immune response to the bacteria that prevents their continued infection of the bloodstream. This stage of infection is rarely fatal.

Cat-Scratch Disease

Cat-scratch disease (CSD) or cat-scratch fever (benign lymphoreticulosis; nonbacterial regional lymphadenitis) is seen throughout the world in immunocompetent persons, primarily in children or young adults, and may affect more than one member of a family. Regional outbreaks have also been reported. Humans are the only species known to develop this disease, which typically manifests as a slowly progressive or chronic enlargement of either a single or regional lymph nodes, accompanied by malaise and possibly fever. It may rarely affect other organs as well.

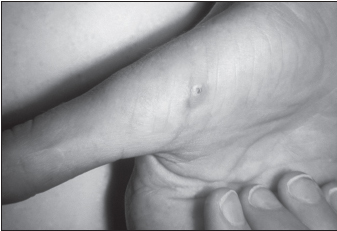

In CSD, lesions develop in one or more lymph nodes, beginning with a primary lesion in the vicinity of the scratch or injury. The lesions are characterized by hyperplasia (increased cell number), formation of a granuloma, and suppuration with a central liquification necrosis (pus-exuding lesion with a dead liquefied center). The nodes become moderately tender. Their pathology is divided into early, intermediate, and late stages. The initial primary lesion may present as a small red papule, vesicle, or pustule occurring approximately 13 days after infection. Few changes are seen in node architecture in the early stage of CSD and include enlargement of the lymphoid follicles and their germinal centers. The follicles are areas of the lymph node rich in lymphocytes of the adaptive immune system, and the germinal centers contain activated B lymphoblasts that secrete antibodies. Regional lymphadenopathy is seen after 3 to 50 days but rarely becomes generalized or involves nodes of other regions.

FIGURE 5.1 Small, localized lesion of cat-scratch disease

Source: CDC/Thomas F. Sellers, Emory University.

The lesion may regress or may progress to the intermediate stage, in which tuberculoid foci appear but multinucleated giant cells (resulting from cell fusion) are rare. Node architecture is noticeably distorted, and the surrounding capsule is often broken. During the late stage, microabscesses and macroabscesses develop, usually within a region of epithelioid cells in a palisade arrangement. The lesions may persist for months.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree