Barriers to adherence and their solutions

Management plans in type 2 diabetes may have many components, which may be extremely challenging. These include dietary and physical activity recommendations, administration of anti-diabetes medications, self-monitoring of blood glucose, foot and eye care, and regular attendance at clinic visits. Add to this the challenges arising from other medications the patient may be receiving for other comorbid conditions, all of which have their own prescribing requirements, as well as tolerability profiles for all prescribed agents, including the potential for drug interactions. In a U.S. survey of older adults with diabetes, 50% reported using at least seven medications in their prescribed treatment regimen, including at least two glucose-lowering agents (Piette et al., 2004). Given all the above factors, it is not too surprising that adherence to management plans is one of the greatest challenges to good diabetes management. Adherence may also vary between different components of the treatment regimen so that each must be considered separately. For example, people may be adherent with their medication (anti-diabetes medication, statin), believing that this means they do not have to be adherent with their diet. In its report on adherence to long-term therapies, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that 52%–70% of U.S. adults with type 2 diabetes adhere to diet, 26%–52% follow a physical activity plan and only about 33% self-monitor blood glucose as often as recommended (Karkashian and Schlundt, 2003).

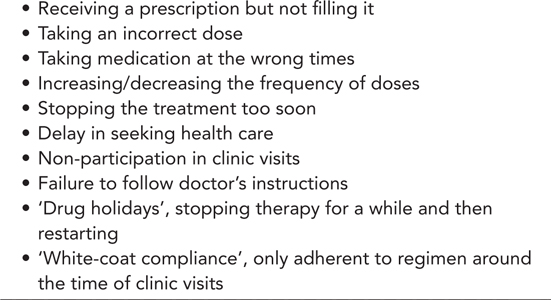

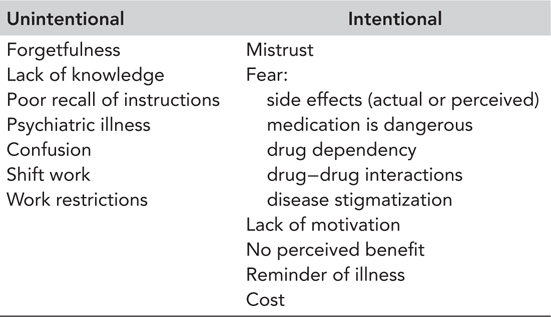

Non-adherence to disease management regimens is widely recognized as one of the major limitations to improving healthcare outcomes (Karkashian and Schlundt, 2003). It may be intentional or non-intentional (Table 3.1) and can present in a number of different forms (Table 3.2). For example, is it because the patient is intentionally disregarding recommendations, or is he or she unable to follow them for some reason? Is there a desire on the part of the patient, but some sort of barrier that precludes adherence?

Regardless of the type of non-adherence, the consequences can be severe. Decreasing levels of adherence are consistently associated with smaller reductions in HbA1c (Farmer et al., 2016). An analysis of data from UK general practice records, which adjusted for confounding factors such as age, sex, clinical values (body mass index, HbA1c, cholesterol and blood pressure), smoking status and morbidity, found that medication non-adherence and clinic non-attendance were independent risk factors for all-cause mortality in people with type 2 diabetes (Currie et al., 2012). Misjudgement of patient adherence can also result in withholding therapy or unnecessary changes in therapy. As a consequence, reduced adherence may not only result in poor health outcomes but can also have a significant impact on healthcare costs. The overall management of type 2 diabetes should therefore address adherence as well as appropriate medications.

Table 3.1 Reasons for non-adherence: Unintentional versus intentional

The majority of diabetes is self-managed with individuals providing around 95% of their own care. However, self-management can be difficult and frustrating for both patients and practitioners, particularly when there is lack of glycaemic control and continued disease progression. It is therefore important for healthcare providers to try and identify which barriers present the greatest obstacles for which patients in terms of their ability to follow the recommended disease management regimen. Once people who are non-adherent and their specific barriers have been identified, the physician can decide on which aspects of diabetes and its management to focus and can tailor adherence interventions to the needs of the individual.

WHICH PATIENTS ARE MOST AT RISK OF NON-ADHERENCE?

Barriers to adherence differ among individuals and can vary over time, but a decline in adherence is most rapid in the first 6 months after starting therapy (Osterberg and Blaschke, 2005). Sometimes, a person’s non-adherence is apparent when he or she returns for a clinic visit because his or her condition has worsened or failed to improve. Others may fail to schedule or to keep appointments or fail to fill or take prescriptions as prescribed. Sometimes, non-adherence may only be discovered by careful monitoring and questioning. Healthcare providers should have a high index of suspicion for non-adherence if any of the above scenarios are regularly observed. In addition, individuals falling into one or more of the categories below may also have a higher risk of non-adherence.

Age-related morbidities

Poor adherence to prescribed regimens can affect all age groups, but older people with type 2 diabetes may be particularly at risk. They may have problems with vision, hearing and memory. It may be more difficult for them to follow therapy instructions due to cognitive impairment or other physical difficulties, such as problems swallowing tablets, opening drug containers, handling small tablets, distinguishing colours or identifying markings on drugs. Age-related alterations in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics and multiple comorbidities and complex medical regimens make this population even more vulnerable to problems resulting from non-adherence. However, most cases of non-adherence in older individuals are likely to be non-intentional, and with help and support from healthcare providers or family members, adherence can be improved.

Lifestyle challenges

People may find it difficult to integrate treatment recommendations and lifestyle interventions into their schedule of daily activity because of work and other commitments. When people are too busy with their work–life schedule, they are more likely to eat unhealthily, skip meals or eat at irregular times, which may result in missing or delaying medication doses. Employment that takes people away from home and shift work also affects adherence, making it harder to follow diet and lifestyle interventions and take medication as prescribed.

Change in situation

Loss or lack of motivation

People may find it difficult to become motivated following a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, particularly when they are asymptomatic even without strict adherence to the treatment regimen and cannot visualize the benefits of long-term therapy. It may take months or years for newly diagnosed individuals to come to terms with the serious health threat posed by diabetes (O’Connor et al., 1997). In this respect, healthcare professionals have a vital role in providing a positive attitude to what needs to be/can be done, but also sensitively imparting information that this is a condition which needs to be taken seriously even if the patient presently feels well. Unfortunately, it is often deteriorating health or major life events that are the impetus for people to make significant lifestyle changes. For others, a lack of motivation may develop over time, for example, in the absence of significant improvements in glycaemic control despite all their efforts to the contrary.

A U.S. survey of people with type 2 diabetes that explored barriers to self-management found that a moderate diet was seen as a greater burden than oral anti-diabetes agents, but less of a burden than insulin, whereas a strict diet aimed at weight loss was rated as being similarly burdensome to insulin (Vijan et al., 2005). Our modern environment can make it difficult to maintain a healthy diet. Inexpensive fast foods high in fat, salt and calories are available everywhere and are heavily marketed so that bad food habits are formed at an early age. At the same time, there is less opportunity for physical activity. Many of us drive to work, sit at a desk or stand at a counter all day, drive home and then relax in front of the television. Although these environmental risk factors are modifiable, they require significant encouragement from the healthcare provider and motivation on the side of the affected individual to look ahead, rather than just focus on short-term achievements such as reducing blood glucose levels.

Depression

The incidence of depression in type 2 diabetes is double that seen in the general population (Anderson et al., 2001) and may negatively affect how individuals take care of themselves. The depression-related symptoms such as loss of interest, impaired decision making ability and fatigue reduce the ability of people with diabetes to manage their condition, which can result in poorer control of blood glucose and difficulty in sticking to exercise, diet and treatment programmes (Egede and Ellis, 2008). Thus starts a vicious circle whereby depression may deteriorate blood glucose control through impaired self-management practices, and poor glycaemic control may aggravate depressive symptoms.

Ethnicity

People from minority ethnic backgrounds often experience particular problems with understanding information about their care, particularly when English is not their first language. These problems are exacerbated by the significantly increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes in these populations (Tillin et al., 2013). Cultural differences in diet, attitude towards exercise, health and religious beliefs, and close attachment to family traditions mean that much of the available information may not be relevant. Individuals from ethnic minorities may also be subject to social inequalities.

Poor perception and knowledge of disease

Most non-adherence is thought to be intentional in that patients make rational decisions not to take the medicine as prescribed based on their knowledge and values. For example, some patients may deny that they are ill. A prescribed medication regimen can therefore only serve as an unwelcome reminder, and the patient is unlikely to adhere to it. Others may have been frightened or confused by media reports around a drug that was once considered safe, but is now associated with health warnings or has even been withdrawn from the market.

Health literacy, defined as the ability to read, understand and remember medication instructions and act on health information (Vlasnik et al., 2005), is also important as it is difficult for patients to take a medicine when they do not understand why it is prescribed, what conditions or diseases it treats or what it prevents.

Problems with therapy

Drug therapy to control blood glucose and associated conditions can only be effective with adherence to the overall prescribed regimen. A number of therapy-related factors can affect adherence, including those associated with the complexity of the dosing regimen, frequent changes in treatment, the immediacy of beneficial effects, fear of injections and/or a therapy, and safety and most importantly tolerability.

COMPLEXITY OF DOSING REGIMEN

The chronic progressive nature of type 2 diabetes means that the complexity of the medication regimen is likely to increase over time. In general, adherence with oral anti-diabetes agents declines as the number of drugs increases (Mateo et al., 2006). Adherence is also inversely proportional to the number of times a day medication must be taken (Claxton et al., 2012). For medication taken only once daily, the average adherence rate is nearly 80%; for medication that must be taken 4 times a day, the average rate drops to about 50%. However, even an adherence rate of 80% means missing one of every five doses of a once-daily medication, or one to two doses per week.

For people struggling with the complexity of a dosing regimen, modifications may involve decreasing the number of therapies and frequency of therapy, and altering the route of administration. There are a number of fixed-dose combinations with different mechanisms of action for the treatment of hyperglycaemia, which demonstrate bioequivalence to the separate tablets, but with reduced pill burden, increased patient adherence and improvements in glycaemic control (Han et al., 2012). Data from a physician interview study have also indicated that the decision to prescribe a fixed-dose combination was associated with improved treatment satisfaction among patients (Benford et al., 2012). Currently available fixed-dose combinations include metformin combined with a sulphonylurea, thiazolidinedione, dipeptidylpeptidase-4 inhibitor, glinide or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor, as well as thiazolidinedione−sulphonylurea combinations. These are available at a range of dosage strengths to facilitate titration.

FEAR OF INJECTIONS

Adherence to injectable regimens is lower than that to oral drugs, and many people with diabetes are reluctant to start them. Some of the barriers to injectable medications can be overcome by education and counselling, but resistance and clinical inertia remains a problem because of the lifelong nature of the disease.

Although most barriers to adherence apply to all therapies, there may be greater and/or additional barriers associated with initiating and adhering to insulin. In addition to fearing needles, many people with diabetes are keen to avoid starting insulin because they believe it signals a worsening of their disease. Other factors often cited as barriers to using insulin include pain of injection, permanence of therapy, restrictiveness and concern about hypoglycaemia and weight gain (Polonsky et al., 2005).

Some healthcare providers may worsen psychological insulin resistance by using insulin as a ‘threat’ if current medications fail to achieve blood glucose control. The mindset of psychological insulin resistance may be minimized by advising people early on and continually that insulin is a safe and effective medication for lowering blood glucose and might be required at some point in their lives to manage the disease. There have also been many improvements in insulin therapy to aid adherence such as the use of pen-like devices to overcome fear of conventional syringe and needles, and the availability of modern insulin analogues, including the rapid-acting analogues (aspart, lispro, glulisine), the long-acting basal analogues (glargine, detemir) and the premixed insulin analogue formulations, all of which have been developed to allow for a closer replication of a normal insulin profile.

SAFETY AND TOLERABILITY

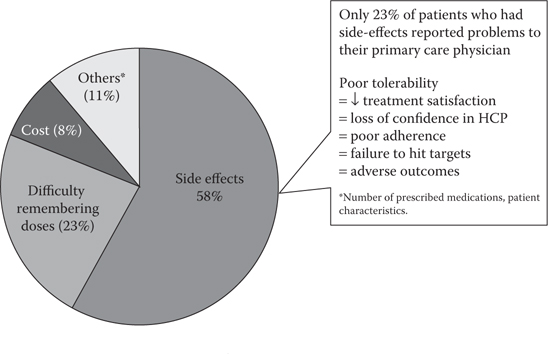

Adverse effects, or fear of adverse effects, can be a major barrier to medication adherence, and indeed some studies have suggested that poor tolerability may be the single biggest reason for poor adherence to pharmacotherapy (Figure 3.1) (Grant et al., 2003). In particular, fear of hypoglycaemia and weight gain may discourage adherence to regimens involving insulin or insulin secretagogues (sulphonylureas and glinides).

Weight gain

A high proportion of people with type 2 diabetes are overweight or obese at diagnosis. An exploratory survey among 121 people with type 2 diabetes showed that 32.8% thought medication would cause unpleasant side effects and 13.9% thought it would lead to weight gain, and these factors were associated with reduced medication adherence (Farmer et al., 2006). In a retrospective study of 294 people with type 2 diabetes, those who were obese or severely obese were more than twice as likely to have low or moderate adherence compared with those who were not obese (Dilla et al., 2008). A range of anti-diabetes medications are available that are either weight neutral or lead to reductions in weight.

Figure 3.1 Most common factors related to non-adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes. (Grant, R.W. et al., Diabetes Care, 26, 1408–1412, 2003.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree