Bacterial Infection

Acute Osteomyelitis

Rapidly progressive pyogenic infection

Types

Hematogenous: usually in children with local trauma

Contiguous: from an open wound, surgical wound, or adjacent area of infection (ear infection, tooth abscess, furuncle)

Biologic response: a function of the inoculum (number and virulence of the organism) and the host response

Spectrum of disease outcomes

Control of the infection, with death of the organisms

Bacteria live in symbiosis with the host.

Bacteria overwhelm the host, causing initially local infection, then sepsis, and possibly death.

Common age ranges, clinical situations, organisms, and initial empiric treatment associated with musculoskeletal infection are listed in Table 27.1-1.

Bacteria develop an effective protective environment, an extracellular polysaccharide glycocalyx, within hours of adherence to bone, biomaterials, and tissue transplants.

Host defenses and antibiotics are excluded by this biofilm or slime.

Table 27.1-1 Typical Organisms Associated with Age or Clinical Situation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hematogenous Osteomyelitis

Pathophysiology

Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis usually presents in the metaphysis of a long bone in a growing child, often with a history of recent trauma.

Postcapillary venous sinusoids of the metaphysis are a preferred environment for infection because of:

Venous pooling with low pO2, turgid flow, and discontinuity of the endothelial lining of the sinusoidal vascular bed

Bacterial adherence to endothelial gaps

Recent trauma may alter local environmental factors.

Small vessel thrombosis further reduces host defenses.

Sequence of events induced by the presence of bacteria in bone

Deposition of the organism at the postcapillary sinusoidal bed, invoking an acute inflammatory response

Increased local capillary permeability, polymorphonuclear (PMN) invasion, and edema

Opsonization, a precoating of the bacteria by opsonins, freely circulating serum molecules that are produced to attach to the surface of microbes, rendering them more attractive to phagocytes (examples of opsonins include IgG antibody and the C3b molecule of the complement system)

Ingestion of bacteria by polymorphs

If not contained by the initial immune response, the infection rapidly produces a compartment-like syndrome: raised intramedullary tissue pressure (from the edema) exceeds the arterial inflow pressure at the capillary level; this eliminates the arteriovenous pressure gradient that drives flow across the capillary, and flow ceases.

Ischemic necrosis then follows the spread of infection throughout the medullary space and through the cortex.

At the outer margin of the cortex, periosteum is lifted off by pus under pressure, severing the subperiosteal circulation.

Cortex is thus isolated from both endosteal and periosteal vascular sources, leading to cortical necrosis.

Diagnosis

Radiologic Features

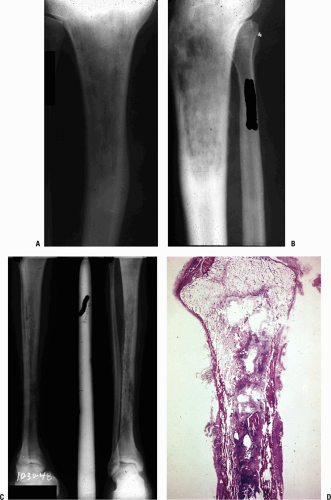

Radiography (Fig. 27.1-1) demonstrates the morphology, with the disease presentation limited to metaphysis and diaphysis, in the distribution of the circulatory beds of the nutrient artery and periosteum.

Infected area creates an irregular zone of osteopenia in the metaphysis, with an external periosteal reaction.

Mottled areas of cortical sclerosis in the predominately lytic area represent areas of cortical sequestration.

Clinical Findings

Presentation is age dependent.

Neonates

Difficult diagnosis

Must be suspected in a neonate who is septic

Neonate may be afebrile.

Affected limb may be warm compared to opposite limb.

Children

Incidence higher in males

Child will look and feel ill.

Refusal to bear weight

Associated factors: recent trauma and infection elsewhere (middle ear infection, tooth abscess, cutaneous boil, or infected wound)

Adults

Advanced age and a variety of systemic factors predispose to the development of bone infection.

Acute vs. chronic infection clinical presentation

Typically, a patient with acute bacterial osteomyelitis may be acutely ill, with acute loss of function of an extremity.

The presence of chronic illness with an impaired immune system or partial treatment with oral antibiotics may mask the presence of infection in bone in adults, especially in the spine.

Spine infection often follows infection elsewhere (pneumonia, diverticulitis, cholecystitis, cystitis, pyelonephritis).

Pain is the predominant complaint: nonmechanical and localized

Lumbar spine 45%

Thoracic 35%

Cervical 20%

Half will have no fever or leukocytosis.

Spread of infection follows vascular supply with segmental arteries supplying disc and adjacent vertebrae.

Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus, and Enterobacter predominate.

Talus and proximal radius are special cases. Hematogenous osteomyelitis can be a difficult diagnosis if bone is “hidden.” Obtain early magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Proximal radius

Enveloped by supinator, acute infection will produce severe pain and forearm swelling and may present with a soft tissue compartment syndrome.

The presence of systemic signs and the absence of a traumatic cause for the raised tissue pressure should suggest the correct diagnosis.

MRI will confirm.

Talus

Infection will mimic cellulitis with pain and local erythema.

Child will not bear weight; an ankle effusion may be sterile.

The site of the infection can be confirmed early only by MRI.

Differential Diagnosis

Osteomyelitis vs. Ewing sarcoma vs. eosinophilic granuloma (Langerhans cell histiocytosis)

The linking of clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic findings is essential to establish the diagnosis.

Ewing sarcoma can perfectly mimic acute or subacute osteomyelitis with fever, malaise, leukocytosis, raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and a radiographic appearance of lysis with a periosteal reaction. Biopsy is needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Eosinophilic granuloma can mimic infection and tumor. The patient is usually not systemically ill. ESR may be elevated; the local findings can include pain and erythema; radiographic picture can be similar to acute osteomyelitis. Biopsy is necessary.

Diagnostic Principles

Extent of disease

Physical findings

Bone tenderness on percussion helps localize infection.

Erythema, fluctuance, and, rarely, drainage in the acute setting

Laboratory parameters: complete blood count (CBC), ESR, C-reactive protein (CRP)

White blood cell (WBC) count with increased PMNs indicates infection but is present in only 50% of patients with infection.

ESR positive in 92% of pediatric patients with osteomyelitis

Time course: rises within 2 days of onset of infection, continues to rise for 3 to 5 days after onset of appropriate antibiotics, and returns to normal at 3 weeks

CRP elevated in 98% of pediatric patients with osteomyelitis; rises within 6 hours of onset of infection, peaks at 36 to 50 hours, and returns to normal 1 week after successful therapy

CRP is preferred for following both acute and chronic infection as it follows the time course of infection more closely.

Surgery delays normalization of both ESR and CRP.

Radiographs (see Fig. 27.1-1)

Initial radiographic sign of infection: soft tissue swelling; always consider tumor or fracture mimicking infection

Lucency occurs with active hyperemia, osteoclast action (Fig. 27.1-2).

Periosteal reaction begins at 2 weeks.

Sclerosis indicates either new bone formation on dead trabeculae or the presence of dead bone (sequestration), surrounded and made more apparent by contrast to living, osteopenic bone.

Technetium 99m (99mTc) bone scan assesses perfusion and osteoblastic activity; localizes pathology but is not specific.

Indium-11-labeled leukocyte scans differentiate infectious from noninfectious causes.

83% to 85% sensitivity, 75% to 94% specificity

MRI can diagnose extent of disease and may show abscess formation.

Sensitivity close to 100%

Increased fluid content in marrow is a function of edema and hyperemia

Decreased marrow signal on T1-weighted images

Increased marrow signal on T2-weighted images

Identify the organism.

Culture the aspirate and obtain cultures at the time of incision and drainage.

Treat empirically while awaiting culture results.

Positive Gram stain in one third of cases; highly specific, allows focused treatment.

Cultures are the gold standard for verifying infection and can be compromised by:

Prior antibiotic administration

Inadequate tissue sampling

Improper handling of specimens

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can amplify and detect bacterial DNA.

Allows early diagnosis compared to cultures

Results are not affected by concurrent use of antibiotics.

False-positive results can arise from contamination.