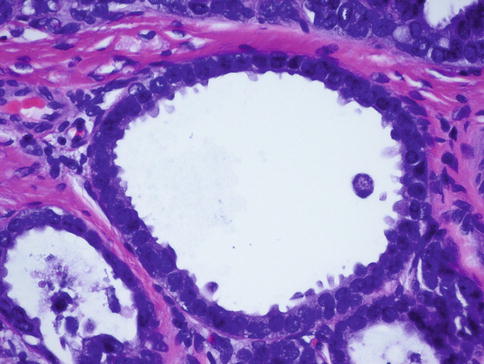

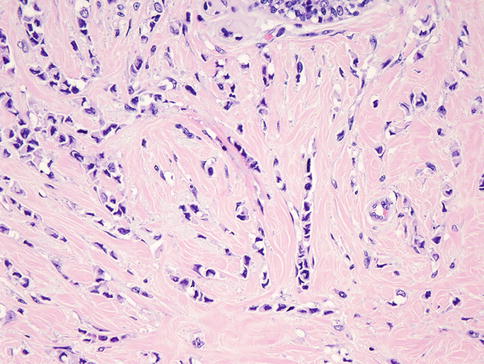

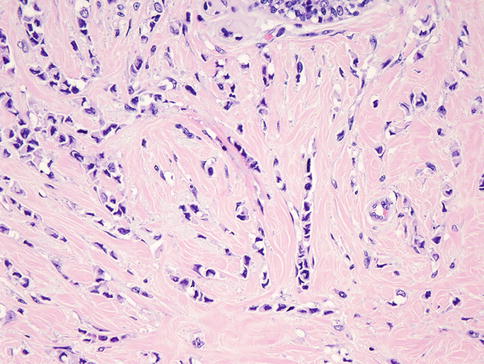

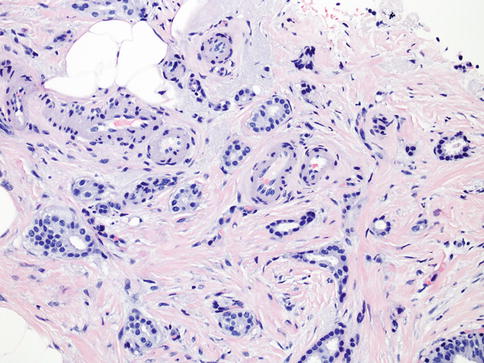

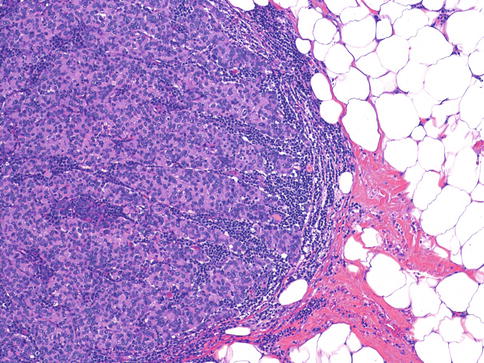

Fig. 35.1

Atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH). The proliferation on the lower side of this lesion has some features of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS); however, the upper part of the lesion has features more characteristic of ADH. Overall, a diagnosis of ADH is favored

Molecular studies on ADH have also identified some genetic abnormalities that are similar to low-grade DCIS [4], which supports the view that these lesions are closely related. It is not surprising that immunohistochemical markers, such as cytokeratin 5/6 (CK 5/6), are being used in diagnosing atypical proliferations of the breast. Such markers can be useful in order to differentiate usual non-atypical epithelial hyperplasia from ADH and low-grade DCIS [5]. Most breast pathologists combine qualitative and quantitative criteria for diagnosing atypical proliferations. When in doubt, they favor a diagnosis of ADH over low-grade DCIS and evaluate the lesion further upon complete removal of the area. ADH is frequently present at the periphery of DCIS lesions [6], and due to the reasons mentioned above, biopsy specimens usually underestimate the presence of higher-grade lesions. It has been reported that at least 30–87 % of patients diagnosed with ADH based on a core biopsy will have an occult carcinoma [7–12]. Therefore, complete removal of the lesion with lumpectomy is currently recommended if the core needle biopsy reveals ADH on final pathology [12].

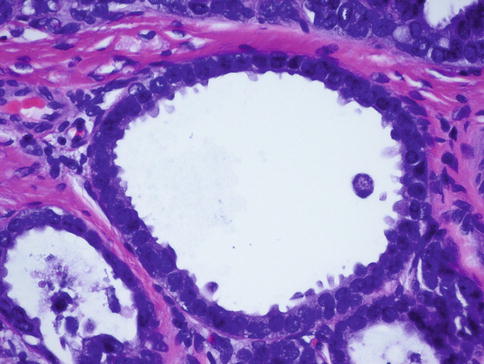

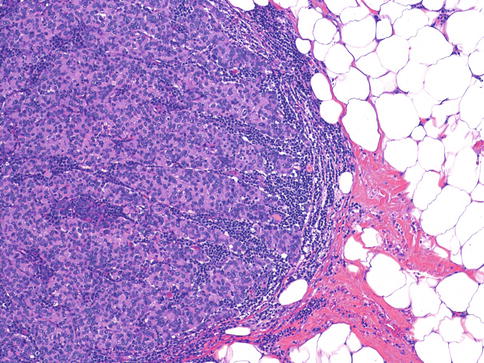

Atypical Lobular Hyperplasia

Atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) is always an incidental finding in breast specimens removed for other reasons. It has no grossly identifiable features and usually lacks microcalcifications. ALH is loosely defined as a hyperplasia that has only some features of lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS); however, this definition is still controversial. Molecularly, ALH can be confirmed with the absence of E-cadherin expression in tumor cells. Most pathologists use both qualitative and quantitative criteria when making an ALH diagnosis. According to Page et al., less than one half of the spaces in a lobule should be filled with, and distended by, lobular cells in order to make the diagnosis of ALH (Fig. 35.2). Anything more than that should be diagnosed as LCIS [2]. The subsequent risk of developing invasive breast carcinoma once diagnosed with ALH is considered to be four to five times higher than the general population [2]. Previously, lobular neoplasia was considered a risk factor for developing invasive breast cancer in both breasts, which warranted a conservative approach [13]. However, recent studies have shown that invasive carcinoma is more likely to arise in the breast diagnosed with ALH, suggesting that ALH acts more like a premalignant lesion [14]. However, the risk of developing invasive cancer approaches the level of LCIS, with ductal involvement by cells of atypical lobular hyperplasia (DIALH) [15].

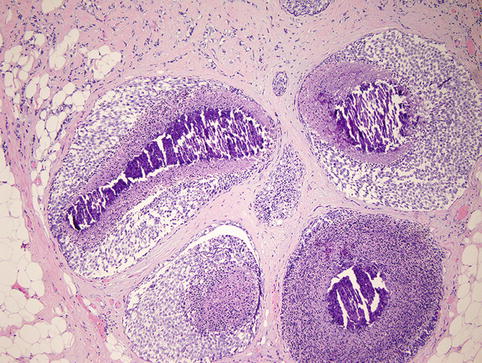

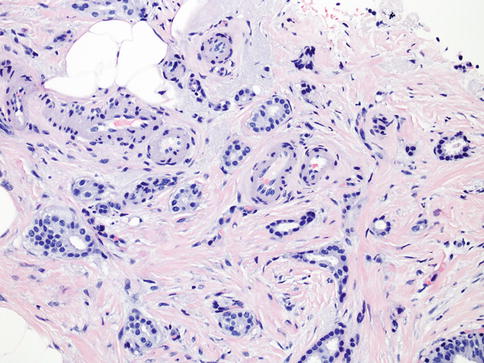

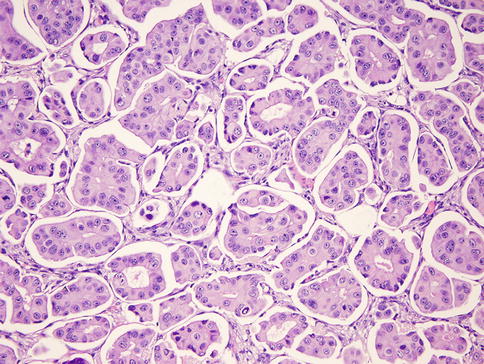

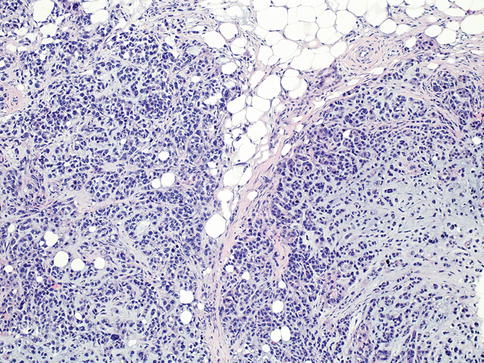

Fig. 35.2

Atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH). ALH shares similar cytologic features with lobular carcinoma in situ and is distinguished by the degree of involvement of lobular structures

The guidelines for the treatment of patients diagnosed with ALH are not clear due to conflicting results in the literature. For instance, the risk of progression to ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive cancer after a core biopsy showing ALH ranges anywhere from 3.1 % to 25 % [16, 17]. The discrepancies in the frequency of worsening diagnoses in different studies may be due to selection criteria in these studies, such as the consideration of various other risk factors within the patient population [17]. The clinical management of ALH is similar to that with ADH, with the current recommendations to completely remove the area with a lumpectomy in most, if not all, cases.

Flat Epithelial Atypia (Columnar Cell Change with Atypia or Columnar Cell Hyperplasia with Atypia)

Flat epithelial atypia (FEA) is characterized by enlarged terminal duct lobular units (TDLU), in which luminal cells are replaced by up to several layers of monomorphic low-grade epithelial cells (Fig. 35.3) [18]. These lesions are flat and do not have the same architectural patterns of ADH or DCIS. Cytologically, the epithelial cells are monomorphic, round, and perpendicular to the basement membrane similar to low-grade DCIS [19, 20]. Additionally, columnar cell lesions have been associated with tubular carcinoma and LCIS [21, 22].

Fig. 35.3

Flat epithelial atypia (FEA). A high-power view shows dilated acini with low-grade monomorphic cytologic atypia characteristic of FEA

Due to its apparent clinical benign nature, FEA was ignored by pathologists for a long time. However, it has gained renewed interest based upon recent observations suggesting that some cases of FEA may progress to invasive breast cancer [23, 24]. For example, one study has shown that there is an approximately twofold increase in breast cancer risk for patients diagnosed with FEA compared to the general population [25]. However, the risk of progression to breast cancer is lower than that of ADH and ALH. Given the limited nature of the data, it is unclear whether the current recommendation for surgical excision following a biopsy diagnosis of FEA is warranted. As a result, radiological-pathological correlation is still recommended in each case [18]. However, many surgeons still recommend complete removal of such areas of FEA, discussing the risks and benefits with each patient.

In Situ Carcinomas

Ductal Carcinoma In Situ

DCIS is a precursor lesion to invasive breast cancer and is defined as a neoplastic proliferation of epithelial cells confined to the ductal lobular unit [18]. Invasive carcinoma, in particular microinvasive carcinoma, ADH, and usual ductal hyperplasia have to be ruled out prior to making the definitive diagnosis of DCIS. Annually, about 14 % of all breast cancers diagnosed in the United States are DCIS, with the risk of death from developing invasive breast cancer after a diagnosis of DCIS very low at about 1–2 % after 10 years [18].

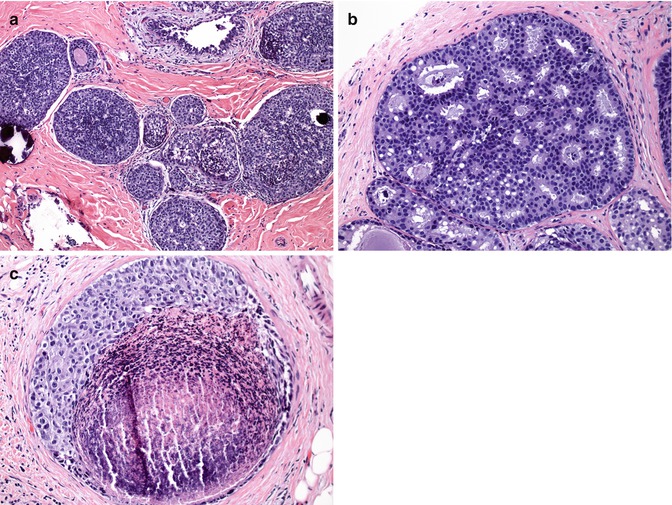

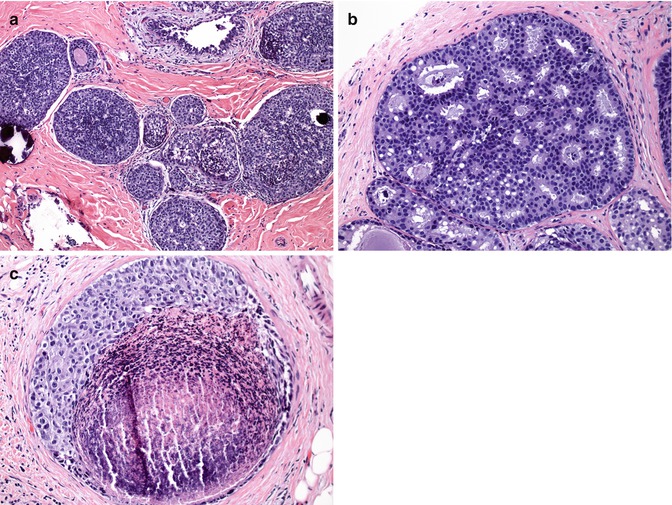

The classification of DCIS can be complex and sometimes problematic [18]. Architecturally, there are five major types of DCIS: cribriform, micropapillary, papillary, solid, and comedo (Fig. 35.4a–c). However, with the newer classification systems, DCIS is divided into only three groups: low grade or grade I (well differentiated or non-high grade without necrosis), intermediate grade or grade II (intermediately differentiated or non-high grade with necrosis), and high grade or grade III (poorly differentiated) [18, 26–28]. Grade I nuclei are defined as large as 1–1.5 red blood cells in diameter with inapparent nucleoli, grade II or intermediate nuclei are 1–2 red blood cells in diameter with coarse chromatin and infrequent nucleoli, and grade III nuclei have >2 red blood cells in diameter with vesicular chromatin and one or two nucleoli [28, 29].

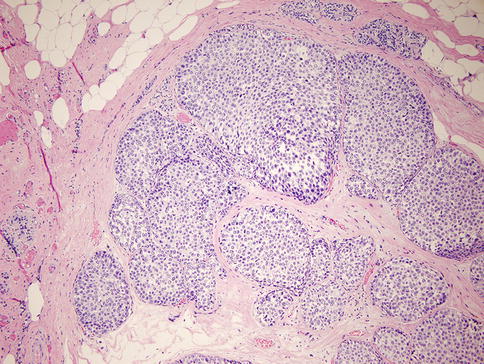

Fig. 35.4

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). DCIS shows different architectural patterns: (a) solid type, (b) cribriform type, and (c) comedo type with necrosis

According to the Consensus Conference on the Classification of DCIS, the following features are recommended to be included in the final pathology report: architectural pattern(s), nuclear grade, type of necrosis (punctate or comedo), and cell polarization [30]. Additionally, the size of DCIS, location of calcifications, and margin status should be reported. Reproducibility of DCIS diagnosis is well known; however, using standardized criteria minimizes discrepancies [3]. As mentioned above, in borderline ADH and DCIS cases, ADH diagnosis is usually favored by pathologists based on biopsy specimens. Importantly, 10–15 % of patients with only a DCIS diagnosis have lymph node metastasis, probably due to an unrecognized component of invasive carcinoma. Therefore, analysis of the draining nodal basin with sentinel lymph node biopsy may be considered and discussed with such patients, particularly for patients with extensive high-grade DCIS [31].

Although the clinical validation of biomarkers is not as comprehensive as in invasive breast carcinomas, testing for estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) is recommended in DCIS [32, 33]. According to the American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations, positive result of ER and PR is defined as ≥1 % of cells showing nuclear staining by immunohistochemistry [33] (Fig. 35.5).

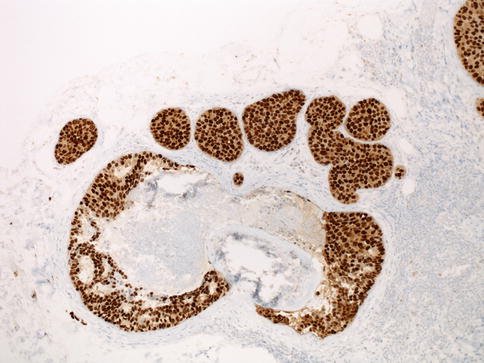

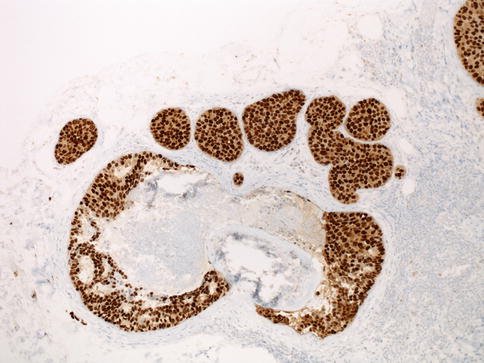

Fig. 35.5

ER (estrogen receptor) staining in ductal carcinoma in situ. Nuclear staining pattern of ER in DCIS

Ductal Carcinoma In Situ with Microinvasion

Microinvasive carcinoma is described as invasive carcinoma measuring less than or equal to 1 mm, which is most commonly seen in a background of high-grade DCIS (Fig. 35.6). Rarely, it is associated with LCIS, and it can also be present alone [18]. Microinvasive carcinomas are more likely to be multifocal [34]. If there are more than one focus of microinvasive carcinoma, the foci should not be added together to determine the stage of the disease [35]. Microinvasive carcinoma needs to be confirmed by demonstrating the absence of the myoepithelial layer by immunohistochemical staining for p63 and smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, since overdiagnosis is a common problem in classifying these lesions [18].

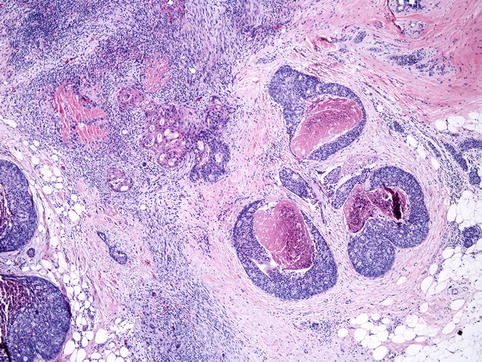

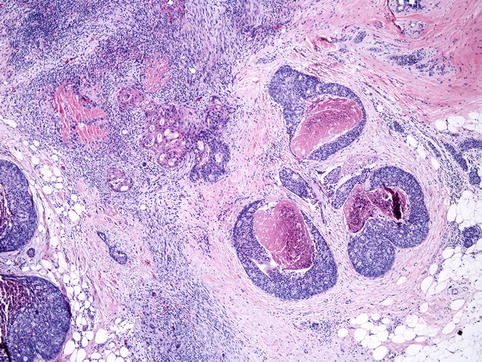

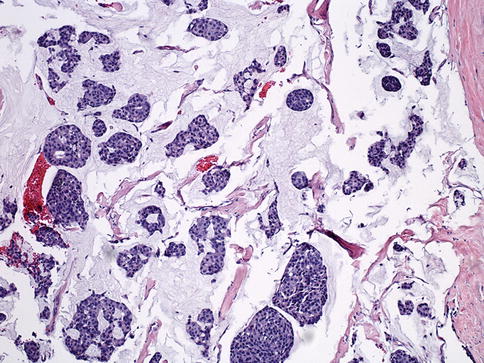

Fig. 35.6

Microinvasive carcinoma. Microinvasive carcinoma is defined by the presence of invasive focus measuring 1 mm or less and is seen next to comedo-type DCIS in the picture

Biomarkers including ER, PR, and HER2 (ERBB2) can be used for microinvasive carcinomas; however, due to small tumor size, detection of these biomarkers may not be possible for each case. In those instances, biomarkers for DCIS should be reported. If no definitive evidence of invasion is found, a diagnosis of in situ lesion is recommended [18]. Sentinel lymph node biopsy should be performed in patients with microinvasion, since 10–14 % of these patients exhibit lymph node involvement [18, 36–38]. The prognosis of DCIS with microinvasion is the same with DCIS of equivalent size and grade [18].

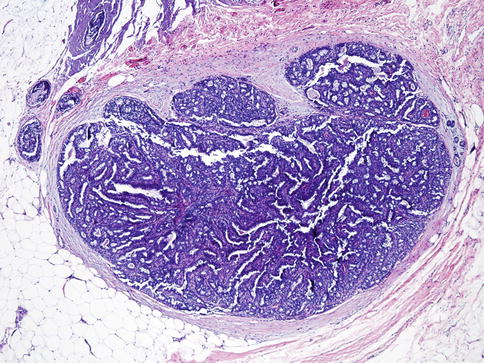

Lobular Carcinoma In Situ

Although atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) are collectively designated lobular neoplasia [18], the risk of developing invasive breast cancer is nine times higher after LCIS (Fig. 35.7) diagnosis, whereas it is four to five times higher after the diagnosis of ALH [18]. Therefore, we believe that the two entities should remain separate classifications, even though the distinction may be arbitrary as described in Section I.B. The distinction between LCIS and ALH is based on quantitative criteria. According to Page et al., LCIS exhibits that at least half of the acini of a lobular unit are distended by atypical epithelial cells that are E-cadherin negative [2]. According to Rosen, at least 75 % of one lobule should be involved to establish an LCIS diagnosis [18]. Rosen holds that lobular enlargement is not an absolute diagnostic criterion for LCIS, due to lobular atrophy observed in postmenopausal women.

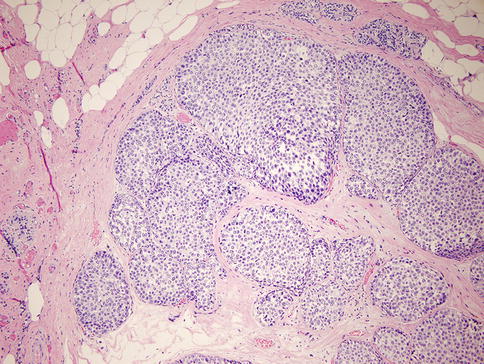

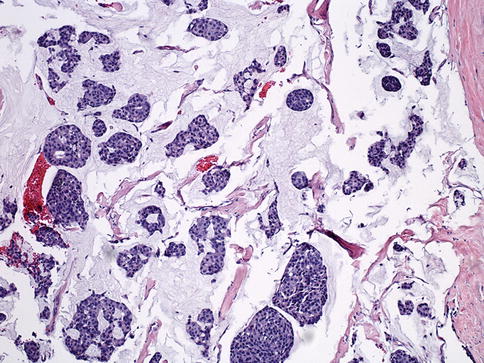

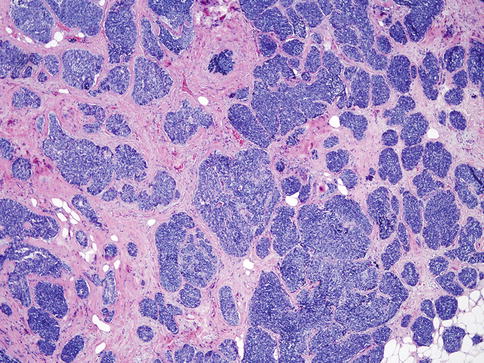

Fig. 35.7

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). The small uniform nuclei fill and distend terminal duct lobular units

Classic LCIS has monomorphic proliferation of dyscohesive epithelial cells with round nuclei, scant cytoplasm, uniform chromatin, and inconspicuous nucleoli [18]. Particularly, two other variants of LCIS are worthy of mention, as they are being diagnosed more frequently due to screening mammograms, although appropriate management for these LCIS variants is uncertain: (1) classic LCIS with comedo necrosis (Fig. 35.8) and (2) pleomorphic LCIS (Fig. 35.9) with high-grade nuclei, sometimes with apocrine features and comedo necrosis [18]. In fact, there is no consensus regarding the management of patients diagnosed with LCIS via biopsy specimens. In some studies, follow-up surgical excisions revealed infiltrating ductal and/or lobular carcinomas in up to 31 % of cases [16]. The largest retrospective study recently showed that 8.1 % of cases with LCIS diagnosis in biopsy specimens received a higher-stage diagnosis upon follow-up excision [17]. Authors of the latter study stress that excision should be considered on an individual basis, taking into account other parameters including age, previous history of breast carcinoma, and the presence of other high-risk lesions.

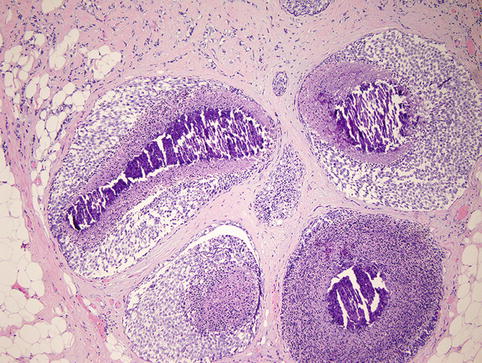

Fig. 35.8

LCIS with comedo-type necrosis mimics ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

Fig. 35.9

Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ (PLCIS). PLCIS is characterized by large cells with marked pleomorphism, abundant cytoplasm, and occasional intracytoplasmic vacuoles. Nuclei are eccentrically located and display conspicuous nucleoli

Histological Classification of Breast Tumors

The WHO classification of the tumors of the breast provides the entire list of breast tumors, including rare types [18]. However, it is beyond the scope of this chapter to cover exceptionally rare types and variants of breast cancer. Instead, we will discuss the most common breast tumors in this chapter. Readers are, therefore, encouraged to refer to classical pathology textbooks for more detailed information about the types of tumors not discussed herein.

Invasive Ductal Carcinoma (Invasive Carcinoma of No Special Type, Ductal Carcinoma NST)

Invasive ductal carcinoma is a default category for the heterogeneous group of tumors that do not show characteristics of a specific histological type, such as mucinous, tubular, or lobular carcinomas [18], and it is the largest group of invasive breast carcinoma (Fig. 35.10), comprising of approximately 40–80 % of all breast tumors [18, 39–41]. Due to tumor cell heterogeneity and differences in grade, microscopic features of invasive ductal carcinomas may vary from case to case. The epithelial component of these tumors may have a glandular architecture, nests, trabecular structures, or solid sheets of tumor tissue in high-grade cancers.

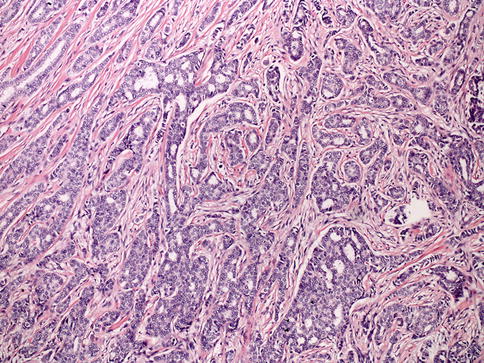

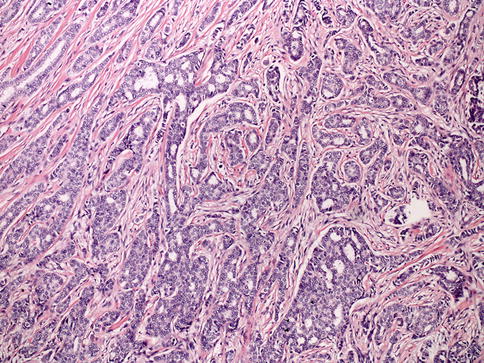

Fig. 35.10

Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC). Low-grade IDC demonstrates tumor cells arranged in trabeculae and cords with diffusely infiltrative pattern

Tissue with clear DCIS features may be entirely separate from the invasive tumor, be incorporated in it, or even dominate it, as up to 80 % of invasive carcinoma cases exhibit a DCIS component [18]. These tumors also can have necrotic foci, minimal to extensive stromal desmoplasia, and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. Overall, prognosis of invasive carcinoma is influenced by tumor-related factors like histological grade, tumor size, lymph node status, lymphovascular invasion, as well as ER, PR, and HER2 status [18]. Approximately 15–20 % of cases are HER2 positive by gene amplification and/or protein expression [42, 43] and approximately 70–80 % of cases are ER positive [44].

Invasive Lobular Carcinoma

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) represents approximately 5–15 % of all breast cancers (Fig. 35.11) [39, 45–48]. The classic variant of invasive lobular carcinoma is a tumor with non-cohesive small cells of low nuclear grade in a single-file pattern with less desmoplastic reaction compared to invasive ductal carcinoma [49]. In addition to this classic variant, there are trabecular, alveolar, and solid variants [50, 51]. Another variant mentioned in the WHO classification is tubulolobular carcinoma [18]; however, recent studies suggest that most of these are a variant of ductal/tubular carcinoma [52–54]. Another subtype, pleomorphic lobular carcinoma (PLC; Fig. 35.12), is an aggressive ILC with higher-grade nuclear morphology, mitotic rate, and apocrine differentiation and is associated with pleomorphic lobular carcinoma in situ (PLCIS) in 45 % of cases [55, 56]. The hallmark of ILC is the loss of the cell-cell adhesion molecule and E-cadherin as well as the loss of alpha-, beta-, and gamma-catenin expression [57–59] and the mislocalization of p120 catenin to the cytoplasm [60–62]. A great majority of ILCs are positive for ER and PR and negative for HER2 [18, 63, 64].

Fig. 35.11

Invasive lobular carcinoma. Tumor cells are small, have relatively uniform nuclei, and invade the stroma in linear strands

Fig. 35.12

Invasive lobular carcinoma, pleomorphic type with a solid growth pattern

Carcinoma of Mixed Type

If more than 50 % of the tumor is a recognized special type, such as lobular, tubular, or mucinous type, and the remainder is a nonspecialized tumor, the tumor is then classified as mixed invasive special type/no special type [18].

Invasive Tubular Carcinoma

Tubular carcinoma (TC) is a special type of invasive breast carcinoma with an excellent prognosis [18, 65]. TC is composed of angulated tubular structures with apical snouts and a cellular desmoplastic stroma (Fig. 35.13). TC may be associated with FEA, low-grade DCIS, and lobular intraepithelial neoplasia [65–67]. TC is almost always positive for ER and PR and negative for HER2 [65, 68].

Fig. 35.13

Tubular carcinoma is an extremely well-differentiated carcinoma characterized by well-formed tubules in over 90 % of the lesion

Mucinous Carcinoma (Colloid Carcinoma)

Mucinous carcinoma (MC) consists of low-grade tumor cells floating in extracellular mucin [18]. Pure MC is associated with a favorable prognosis [69] (Fig. 35.14) and is defined as tumors composed of more than 90 % (even close to 100 %, according to some studies) of tumor tissue with characteristic histology [70]. Typically, MCs are positive for ER and PR [69] and negative for HER2 [71].

Fig. 35.14

Mucinous carcinoma. Mucinous carcinoma is a well-differentiated carcinoma characterized by the presence of extracellular mucin around the tumor cells in at least 90 % of the tumor

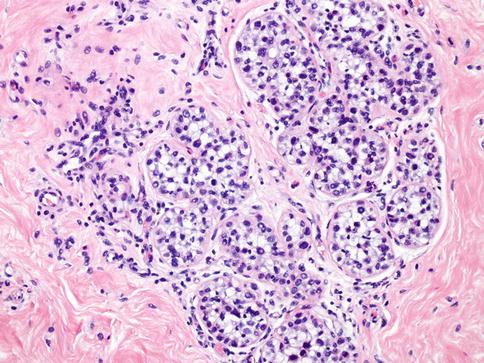

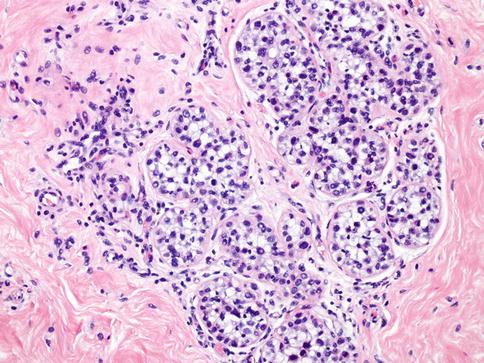

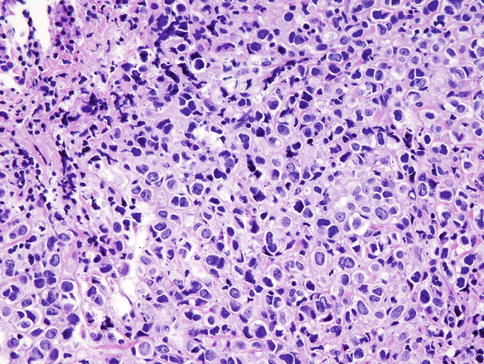

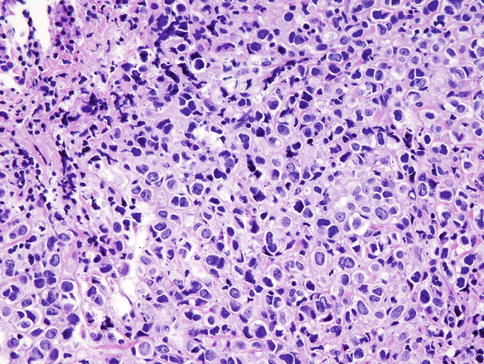

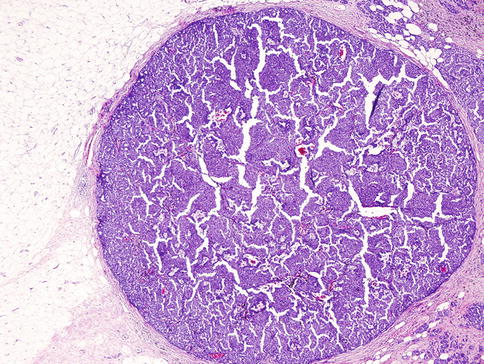

Carcinomas with Medullary Features

Carcinomas with medullary features (CMF) are a group of breast tumors (Fig. 35.15) including medullary carcinoma, atypical medullary carcinoma, and invasive carcinomas of no special type with similar histological features, such as prominent lymphoid infiltrates pushing borders and high nuclear grade with a syncytial growth pattern [18]. These cancers are grouped together in the latest WHO classification [18] due to poor interobserver reproducibility. The prognosis of medullary carcinoma is unclear, with some studies showing no survival advantage over other types of carcinomas with no special type [39] and others showing favorable long-term prognosis [72]. Similar to basal-like triple-negative carcinomas, CMFs are mostly negative for ER, PR, and HER2 (i.e., triple negative) and positive for keratins 5/6 and 14 and EGFR [18].

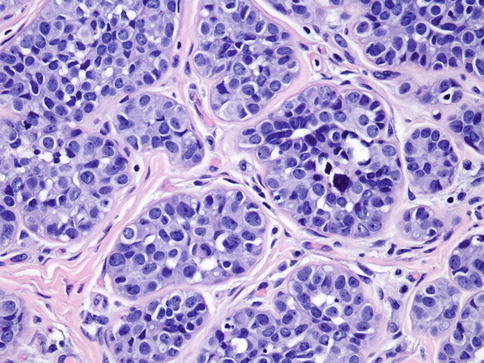

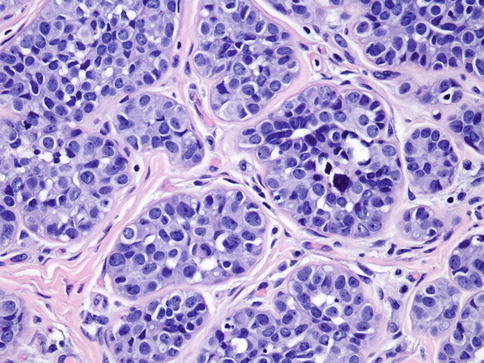

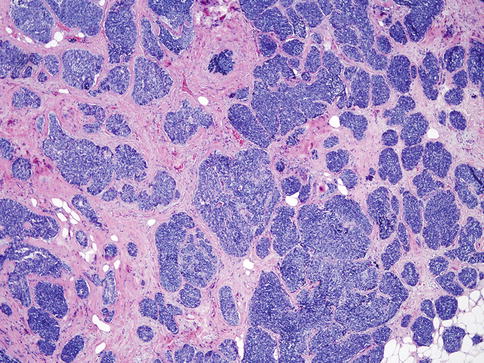

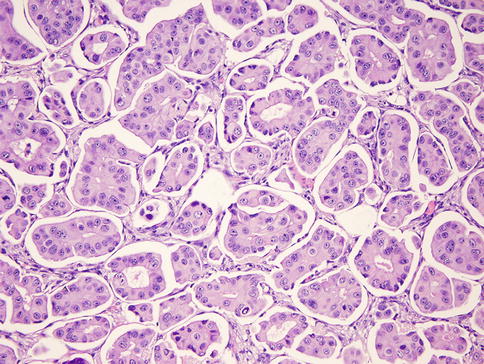

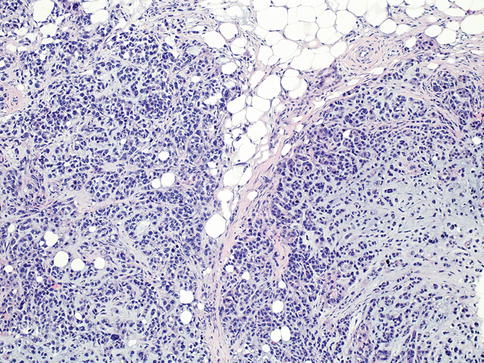

Fig. 35.15

Carcinomas with medullary features are well-circumscribed tumors with high nuclear grade, syncytial growth pattern, and prominent lymphocytic infiltrate

Intraductal Papillary Lesions and Invasive Papillary Carcinoma

Terminology and accurate diagnosis of papillary lesions of the breast are difficult due to heterogeneous group of lesions. These lesions encompass benign, in situ, and invasive cancers [18] (Table 35.1, Figs. 35.16, 35.17, and 35.18).

Table 35.1

Characteristics of benign, in situ, and invasive papillary tumors

Tumor type | Myoepithelial cell layer at periphery of involved ducts | Histological characteristics | ER and PR status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Intraductal papilloma | Benign | Present | Benign fibrovascular cores covered by an epithelial and myoepithelial cell layer | Patchy positive |

Intraductal papilloma with ADH/DCIS | In situ lesion | Present | Part of the papilloma has features of ADH/DCIS | ADH/DCIS component: diffusely and strongly positive |

Intraductal papillary carcinoma | In situ lesion | Present | Papillary DCIS | Diffusely and strongly positive |

Encapsulated papillary carcinoma | In situ/low-grade invasive | Usually not present | Fibrovascular cores covered by neoplastic cells. Absence of myoepithelial cells in the lesion or periphery of the lesion | Diffusely and strongly positive |

Solid papillary carcinoma | Invasive | Not present | Expansile, solid growth of tumor with delicate fibrovascular cores and neuroendocrine features | Diffusely and strongly positive for ER/PR and negative for HER2 |

Invasive papillary carcinoma | Invasive | Not present | Invasive adenocarcinoma with papillary morphology | Not well characterized |

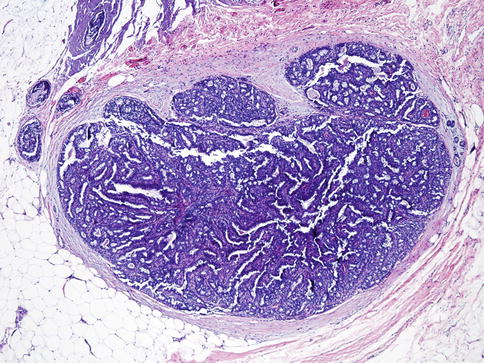

Fig. 35.16

Benign intraductal papilloma. Intraductal papilloma shows well-defined thin fibrovascular cores originating from duct walls lined by myoepithelial and ductal cells. Cytologic atypia is rare

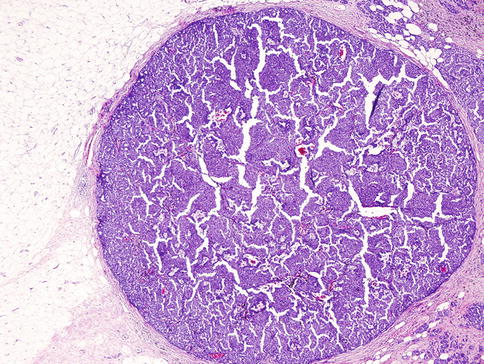

Fig. 35.17

Encapsulated papillary carcinoma. Low-power view shows well-circumscribed lesion with papillary proliferation of uniform neoplastic cells. Myoepithelial cells are absent both in the lesion and periphery of the tumor

Fig. 35.18

Solid variant of papillary carcinoma. The tumor is composed almost entirely of solid pattern with intermingled fibrovascular network and no apparent papillary structures. The cells are monotonous with a low to intermediate nuclear grade in most of cases

Invasive Micropapillary Carcinoma

Invasive micropapillary carcinoma (IMPC) is an aggressive variant of invasive ductal carcinoma (Fig. 35.19) with very frequent lymphovascular invasion and lymph node metastasis [73]. The micropapillary clusters lack fibrovascular cores and have an “inside-out” growth pattern, in which apical cells face the empty stromal spaces rather than the luminal surface [74]. The majority of both pure and mixed micropapillary carcinomas show similar phenotypes, including ER- and PR-positive status and HER2-negative status [75].

Fig. 35.19

Invasive micropapillary carcinoma. The micropapillary clusters lack fibrovascular cores and apical cells face the empty stromal spaces

Metaplastic Carcinoma

Metaplastic carcinomas (MCs; Fig. 35.20) are a heterogeneous group of tumors with cells differentiated into squamous- and/or mesenchymal-like elements (e.g., spindle, chondroid, osseous, and rhabdomyoid cells) [18, 76–78]. The tumor may be composed of carcinomatous and metaplastic regions or, in some cases, only of metaplastic areas. Variants of this group include low-grade adenosquamous carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma, metaplastic carcinoma with mesenchymal differentiation, and mixed metaplastic carcinomas [18]. Characteristically, metaplastic tumors are ER, PR, and HER2 negative [79]. Overall survival in the metaplastic carcinoma group is worse compared to the poorly differentiated carcinoma group [80].

Fig. 35.20

Metaplastic carcinoma. The tumor shows high-grade carcinoma with cartilaginous differentiation

Phyllodes Tumors

Phyllodes tumors (PT; Fig. 35.21a, b) are included in the general category of fibroepithelial tumors along with fibroadenomas consisting of both epithelial and stromal components [18]. Based on the WHO criteria, PTs are classified into three groups [18] (Table 35.2).

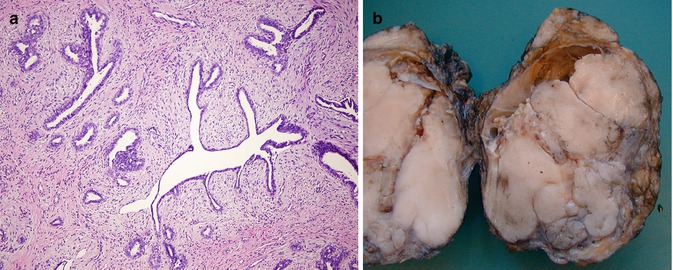

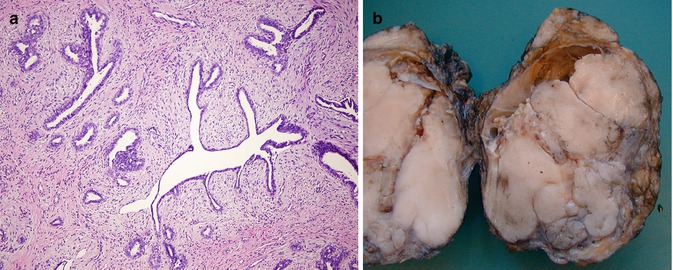

Fig. 35.21

(a) Benign phyllodes tumor. This lesion exhibits cleft-like spaces and leaflike projections with a cellular stroma. (b) Malignant phyllodes tumor (gross picture)

Table 35.2

WHO classification of phyllodes tumors (PTs)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree