Abstract

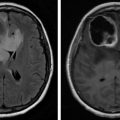

Palliative rehabilitation is focused on the optimization of the functionality and quality of life of individuals in the advanced stages of cancer. Care is delivered in the context of a transdisciplinary team model and is driven by the values and preferences of the patient with the assent of their closest communication partners. The care model is person-centered with a focus on preservation of capabilities and potentially time-limited goals that address concerns identified by the person served as meaningful and of personal significance in sustaining dignity and self-esteem. In this sense, palliative care and cancer rehabilitation share a common approach and philosophy, facilitating their integration in supportive oncologic care. In this chapter, the elements of a palliative rehabilitation program provided in the context of palliative care for advanced cancer will be examined. Physical rehabilitation must be closely integrated with psychosocial interventions addressing the psychologic distress, existential anxiety, and spiritual pain that often arise in the process of person-centered and family-oriented care in both patients and caregivers struggling to come to terms with the exigent experience of advanced cancer. Clear communication about therapeutic goals and end-of-life preferences including the specification of advanced directives is critical and should occur while the patient retains capacity to relate their requests unambiguously. Some of the issues impacting palliative rehabilitation associated particularly with neoplastic disease involving the central nervous system will also be considered.

Keywords

Advanced cancer, Caregiver burden, End-of-life preferences, Palliative rehabilitation, Person-centered healthcare, Quality of life, Supportive oncology

Introduction

The point at which active standard oncologic treatment is determined to be more likely to cause greater symptom burden than benefit for patients with advanced cancer is a critical transition which had been generally interpreted in the past within an obsolete conceptual understanding as implying the complete withdrawal of active medical care—at a particular time when, from the perspective of the patient and family, care—including rehabilitation services—may actually be most needed. This may explain the tendency toward an underutilization of cancer rehabilitation services integrated within a palliative care program. However, this situation is changing rapidly as the significant benefit of interdisciplinary palliative care with embedded function-oriented rehabilitation treatment is recognized as a means of optimizing patient autonomy, self-esteem, and quality of life (QoL), as well as a measure for reducing avoidable suffering and healthcare costs, during a time when both patient and their caregiving partners have significant care needs. The point at which a move toward palliation occurs is thus better viewed as a carefully guided shift in emphasis of treatment and focus of care for individuals with advanced cancer rather than as a “withdrawal” of treatment.

Palliative care is defined by the World Health Organization as:

An approach that improves the QoL of patients (adults and children) and their families who are facing problems associated with life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial or spiritual. Addressing suffering involves taking care of issues beyond physical symptoms. Palliative care uses a team approach to support patients and their caregivers. This includes addressing practical needs and providing bereavement counselling. It offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death. Palliative care is explicitly recognised under the human right to health. It should be provided through person-centred and integrated health services that pay special attention to the specific needs and preferences of individuals.

The American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends that palliative care should be combined with standard oncologic care early in the course of treatment for all patients whose cancer is considered “advanced”—typically those with identified metastatic disease and/or a high symptom burden. Essential components of a palliative care program are listed in Table 15.1 .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends that all cancer patients be repeatedly screened for palliative care needs, beginning with their initial diagnosis and thereafter intermittently as indicated. Patients who screen positive for inadequately controlled symptoms, moderate to severe distress and anxiety, or otherwise serious physical, psychiatric, and/or psychosocial comorbidity, metastatic solid tumors, life expectancy of less than 6 months based on recognized indicators, patient or family concerns about the course of the disease and the associated decision-making process, or specific patient and/or family requests for palliative care should receive a palliative care referral.

There is mounting evidence demonstrating that participation in an integrated and appropriately timed palliative care treatment program helps to both enhance the QoL near the end of life for patients as well as their caregivers and reduce associated healthcare costs. Cancer rehabilitation and palliative care are subspecialties that share a common holistic, person-centered philosophy of care, implement comprehensive services through interdisciplinary teams, and are focused on improvement of health-related QoL, symptom-oriented management, and the lessening of caregiver burden.

Cheville et al. define “palliative rehabilitation” as follows:

Palliative rehabilitation is function-directed care delivered in partnership with other disciplines and aligned with the values of patients who have serious and often incurable illnesses in contexts marked by intense and dynamic symptoms, psychologic stress, and medical morbidity, to realize potentially time-limited goals. [p. S337]

In some centers, palliative care and rehabilitation are each classified as components of a “supportive oncology” program where supportive oncology is identified as “the provision of the necessary services for those living with or affected by cancer to meet their informational, emotional, spiritual, social, or physical needs during their diagnostic, treatment, or follow-up phases encompassing issues of health promotion and prevention, survivorship, palliation, and bereavement.” ( , p. 372).

In this chapter, we will examine the role of function-oriented, comprehensive rehabilitation treatment in the context of the palliative care of individuals with advanced cancer with special consideration to neoplasms involving the central nervous system.

The General Role of Rehabilitation in Advanced Cancer

Rehabilitation derives from the Latin “rehabilitare” meaning to make fit again. Cancer rehabilitation is a process that assists the individual’s physical, social, psychologic, and vocational functioning within limits imposed by the acquired pathology. The functional autonomy of patients with cancer is compromised throughout the trajectory of illness in different ways and influenced by different factors. The severity of this compromise can range from negligible to profound.

Patients with advanced cancer and their families highly value control of symptoms, maintenance of function and nutrition, and improvement in quality of life, as do their physicians. Yet, although drug protocols for cancer are clearly outlined, formal programs addressing symptoms and the functioning of the person are not common. To achieve these goals, a multimodal approach that includes the full spectrum of rehabilitation and the involvement of a coordinated interdisciplinary rehabilitation team of professionals from the onset of advanced cancer is essential. There is emerging clear evidence that certain dietary patterns, exercise, and a healthy psychosocial status and attitude influence cancer incidence and early progression. “Survivorship” programs that embrace these entities are now well accepted. However, few centers provide comprehensive care models that adequately address the complex needs of patients with advanced cancer, together with the needs of their caregivers.

While some patients may experience symptoms during the initial phases of diagnosis and treatment, others experience treatment-related, long-term, debilitating side effects. Following initial cancer diagnosis, patients react differently, progressing at different rates through different phases, characterized by symptoms which affect specific functional domains, requiring specific rehabilitation interventions. Post-treatment rehabilitation directed toward time-limited functional treatment goals has been shown to improve physical symptoms (such as fatigue and physical endurance), nutritional symptoms (such as poor appetite, unintentional weight loss, and nutritional deterioration), psychologic symptoms (such as anxiety, depression, and immobilizing apprehension), and overall quality of life.

Epidemiologic Considerations

There were an estimated 14.1 million new cancer cases, 8.2 million cancer deaths, and 32.6 million people living with cancer (within 5 years of diagnosis) in 2012 worldwide. The overall age-standardized cancer incidence rate is almost 25% higher in men than in women, with rates of 205 and 165 per 100,000. It is estimated that 70% of all the patients with cancer survive for more than 5 years after the date of diagnosis and the majority of the cancer survivors are of working age (<55 years). Improved outcomes with extended survival times have, therefore, created a constantly growing population of patients living with a cancer diagnosis. In 2016, there were an estimated 14.5 million cancer survivors in the United States. Breast cancer survivors continue to represent the largest segment of the survivor population (23%), followed by prostate cancer survivors (21%) and colorectal cancer survivors (9%). By January 1, 2026, it is estimated that the population of cancer survivors will increase to 20.3 million: almost 10 million males and 10.3 million females.

Classification of Rehabilitation Needs

In 1969, Dietz introduced the first conceptual framework for designing a successful rehabilitation program triaging patients based on their rehabilitation goals and needs. Owing to the nature of the cancer trajectory, rehabilitative goals have been divided into preventive, restorative, supportive, and palliative.

Preventive rehabilitation aims at reducing the burden of morbidity/mortality of the disease and/or treatment. Rehabilitation interventions include education concerning the functional impact of the treatment, specifically preserving social function and activities of daily living (ADLs).

Restorative care aims to return the individual with minimum functional impairments to their premorbid state. Postoperative range-of-motion (ROM) exercises for patients undergoing reconstructive surgery for head and neck cancer represent this category of care.

Supportive efforts seek to reduce functional difficulties and compensate for permanent deficits. An example of this approach would include the multimodal techniques used to rehabilitate patients after amputation. Rehabilitation intervention aims at developing a program to restore mobility and management of symptoms that can occur as a result of the primary disease as well as treatment effects.

Palliative treatment aims to eliminate or reduce complications, especially pain and any other symptoms associated with impaired functioning. Emotional support at this stage is also clearly important. Prevention of bedsores can be achieved by education of caregivers. Existential issues can also be addressed sensitively by clergy and other palliative care team members. Rehabilitation intervention for this phase focuses on educating the patient and their caregivers on how to conserve energy and optimize physical capability in the face of the pathophysiologic effects of advanced cancer.

Psychosocial Interventions in Patients With Advanced Cancer

Psychosocial problems and psychologic distress are common consequences of cancer and its treatment and can often become a major issue in palliative care as existential concerns emerge. The term “distress” refers to emotionally difficult experiences that may be in response to psychologic, social, spiritual, or other sources of suffering linked to existential uncertainty. Distress becomes a significant clinical concern when it precipitates significant disturbance and disorder interfering with one’s ability to engage socially or function in daily life.

In cancer care, this may manifest as difficulties engaging constructively with clinicians, seeking appropriate medical or supportive care, adhering to treatments, coping with losses, or adjusting to the existential uncertainty that accompanies advanced cancer. Interventions can help patients attend to factors of distress that interfere with their functioning or QoL. In addition to helping patients address distress, psychosocial clinicians embedded in the rehabilitation team can also help patients improve other physical difficulties, such as pain, sleep, fatigue, or other debilitating physical concerns. Canadian psychosocial scientist-practitioners spearheaded efforts to successfully have distress recognized as the sixth vital sign in cancer care. In 2008, screening for distress became an accreditation standard for all Canadian cancer programs under Accreditation Canada. In the United States, the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (CoC) adopted a similar screening policy in 2016 for all CoC-accredited cancer programs. The consensus report issued by the US Institute of Medicine (IOM) specified processes that need to be in place to (1) identify distressed patients; (2) link patients and families to needed psychosocial services; (3) support patients and families in managing the illness; (4) coordinate psychosocial and biomedical care; and (5) follow up on care delivery to monitor the effectiveness of services provided and make modifications if needed. These recommendations are similar to those contained in the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Distress developed by the US NCCN. Similar to the IOM report, the NCCN guidelines recommend that all patients be routinely screened with validated measures to identify the level and sources of their distress. This could be accomplished using the single-item “Distress Thermometer” and the accompanying problem checklist described in the guidelines. Canadian guidelines recommend the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) and the problem checklist as the minimal toolkit. The ESAS provides nine single-item scales that screen for the severity of nine common symptoms, including depression and anxiety. A published randomized trial has demonstrated the benefits of an approach to psychosocial care similar to that described in the NCCN guidelines. In this study, cancer patients found to have major depressive disorder through a screening process were randomly assigned to usual care or usual care plus a collaborative care intervention, termed “Depression Care for People with Cancer,” delivered by a specially trained oncology nurse. Findings showed significantly lower scores on a measure of depression 3 months post randomization for patients who received the collaborative care intervention. The beneficial effects of the collaborative care intervention observed at 3 months were still evident at 6-month and 12-month follow-up assessments. Emotional distress manifests at different points of the cancer clinical trajectory in different forms. Anxiety is frequently observed in association with the diagnostic phase, whereas depressive symptoms are more insidious and are seen in higher incidence later in the clinical course of the disease.

Another more recent study investigated the factors associated with psychologic distress in advanced cancer patients under palliative treatment. Patients with high and low distress were compared according to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Based on the development of a multivariate prediction model, the authors concluded that “high levels of hopelessness, impaired emotional functioning and body image distortions are the main factors associated with psychologic distress in patients with advanced cancer.” [ , p. 608] Potential interventions to modify these specific factors in palliative care units are then presented by the authors.

A recent randomized clinical trial with results presented at the ASCO conference in 2017 suggests that a brief structured psychologic intervention, called “Managing Cancer and Living Meaningfully” (with the assigned acronym CALM), could help significantly relieve distress in patients with advanced cancer. CALM is a psychologic intervention that consists of three to six 45- to 60-min sessions delivered over three to 6 months by trained healthcare professionals, such as social workers, psychiatrists, psychologists, palliative care doctors and nurses, and oncologists. The sessions focus on four broad domains: (1) symptom control, medical decision-making, and relationships with healthcare providers; (2) changes in self-concept and personal relationships; (3) spiritual well-being and the sense of meaning and purpose in life, and (4) future-oriented concerns, hope, and questions about mortality. In this study, at both 3 and 6 months, the CALM treatment group was better prepared for the end of life and they had greater ability to express and manage their feelings about it. At 6 months these effects were strengthened, and the CALM group was more prepared to deal with changes in relationships due to the cancer, and they were also able to better clarify and articulate their values and beliefs.

Important work has also been done on developing a systematic brief psychotherapeutic intervention designed to address the challenge of helping persons with advanced cancer who are nearing the end of life maintain a sense of dignity in the face of significant uncertainty about their future and to attempt to mitigate the distress precipitated by such uncertainty. Chochinov et al. have developed a dignity model of palliative care directed toward decreasing suffering, enhancing QoL, and augmenting a sense of meaning, purpose, and dignity through the offering of opportunities to address concerns that are of greatest meaning and significance to the patient as well as the chance to speak about how they would most want to be remembered by those who survive them. Dignity Therapy also provides for encouragement to recognize and take pride in various accomplishments and to cherish their legacy. The patient is provided with an edited transcript of these guided discussions with the therapist that they are then encouraged to share with friends and family as a precious bequest. Themes that guide these sessions include generativity, continuity of self, role preservation, maintenance of pride, hopefulness, aftermath concerns, and care tenor. While a controlled trial of the described dignity-focused therapy did not demonstrate a significant reduction per se in patient distress, those provided with this form of psychotherapeutic intervention reported an improved QoL and sense of dignity as well as improvement in family relationships.

Another approach to the treatment of intractable depression and existential psychospiritual distress or “spiritual pain” —defined as “pain caused by extinction of the being and the meaning of the self” [ , p. 15] evaluated according to the three dimensions of temporality, relationship, and autonomy—has been the application of hallucinogenics in combination with an intensive single session of supportive psychotherapy while the patient is experiencing the hallucinogenic effects of the drug. A randomized double-blind controlled trial in 51 advanced cancer patients using high- versus low-dose psilocybin, a serotoninergic classic hallucinogen derived from mushrooms, demonstrated large and sustained decreases in clinician- and self-rated reports of depressed mood and anxiety together with improved quality of life, life meaning, and sense of optimism in the high-dose group. The authors postulated that the beneficial effect of high-dose psilocybin was mediated by “mystical-type psilocybin experience” occurring during the closely monitored single-treatment session on the day of drug administration. In reviewing their experience with this form of treatment, Grob and Griffiths made the following statement:

A unique aspect of utilizing a classic hallucinogen (e.g. psilocybin) to treat the severe psychologic demoralization and existential anxiety seen in life-threatening medical illness is its seeming capacity to facilitate powerful states of spiritual transcendence that exert in the patient a profound therapeutic impact with often dramatic improvements in psychologic well-being. For a patient population struggling with often overwhelming levels of existential anxiety and demoralization, such a therapeutic intervention may have the capacity to re-infuse a sense of meaning and purpose into their lives. [p. 305]

Future research into this potentially powerful and promising approach to the management of existential anxiety and demoralization, as well as intractable depression in patients with advanced cancer is clearly warranted.

Another emerging approach to management of anxiety and mood disorders in patients with advanced cancer are mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs). A recently published literature review examining the value of MBIs in the treatment of psychologic concerns in both patients and caregivers in the scenario of advanced cancer suggests that MBIs can be beneficial to the advanced cancer population with an associated improvement in quality of life, together with acceptance of their cancer situation and associated reduction in depression and anxiety. In their extensive review of the research literature, Rouleau et al. note that, although accumulating evidence suggests that participation in an MBI may contribute to reductions in psychologic distress, sleep disturbance, and fatigue, while promoting personal growth in areas such as QoL and spirituality, care must be taken to balance these potential benefits against the limited scientific evidence supporting their measurable impact on specific clinical outcomes.

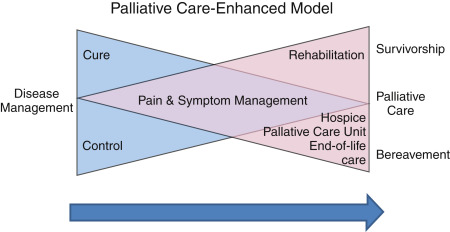

Survivorship and Rehabilitation

A new model to describe palliative care was recently introduced; one that prepares the patients for the worst (death), but still allows hope for the best (cure). It helps illustrate the possibility of dying at a time when patients’/families’ thoughts may be occupied by hope of cure. The model consists of two overlapping triangles resembling a bow tie ( Fig. 15.1 ). The first triangle represents disease management and the second triangle is palliative care. The base of the palliative care triangle (end of the model) includes both death and survival as possible outcomes. The arrow, pointing from left to right, signifies this dynamic process with a gradual switch in focus. Survivorship, a unique aspect of this model, is included as a possible outcome. It may be used to illustrate where the various components of modern supportive and palliative care might fit into the patient’s journey along with anticancer treatments.

Communication and Clarification Regarding End-Of-Life Preferences

One of the most challenging areas in which clinicians are involved when treating individuals with advanced cancer is ensuring that communication about end-of-life preferences is clear and established relatively early in the process. This is of particular concern when cancers involve the brain and thus may significantly impact the cognitive capacity and judgment of the person and affect their ability to communicate lucidly and make clear and definitive judgments about decisions and directions that are emotionally charged and of existential consequence. This issue becomes an increasingly significant issue as the cancer progresses. It is also important that a clear consensus about personal preferences is established among the communication partners of the person and that the wishes of the person be respected and supported by all concerned. Communication with patients and families presents a number of difficult challenges including the need for a clear and direct discussion of prognosis and about what can be expected as the cancer advances; the challenges encountered in managing emotionally charged situations, questions, and concerns related to the nurturing of hope; and the recognition of the central importance of culturally dependent factors such as religious belief and spirituality. This can thus frequently be a complex and exacting task, and it will not be dealt with in detail here. The reader is referred to a monograph on the topic produced by an expert panel convened by the Institute on Medicine and published by the National Academies Press.

This summary of this influential report concludes as follows:

In sum, the committee believes that a patient-centered, family-oriented approach to care near the end of life should be a high national priority and that compassionate, affordable, and effective care for these patients is an achievable goal. [p. 20]

Palliative Rehabilitation as Implemented at the Élisabeth Bruyère Hospital—An Innovative Team Approach

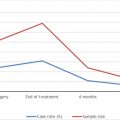

One of Dietz’ cancer rehabilitation categories listed above, palliative rehabilitation, was largely neglected until approximately the past decade. Palliation and rehabilitation both focus on QoL and daily functionality as opposed to cure or survival. As noted earlier, they are both person-centered, involving the patient, the family, and other relevant aspects of the environment. They incorporate the expertise of multiple specialized professionals and accordingly both have biopsychosocial traditions. Together, palliation and rehabilitation stand to improve function and QoL for patients with complex or advanced cancer. The Élisabeth Bruyère Palliative Rehabilitation Program (PRP) in Ottawa, Canada, was modeled after the McGill Cancer Nutrition and Rehabilitation program with some notable differences. The PRP specifically took a palliative rehabilitation approach, targeting patients with complex cancer. Patients of the PRP were adults with diagnosed incurable advanced heterogeneous cancers, typically classified as stage 3 or 4. Patients had completed their cancer treatments, were medically stable, were motivated to participate in the program, and were experiencing symptomatology and limitations that impaired their ability to engage in a productive daily life (e.g., physical dysfunction, malnutrition, mental health concerns). They needed to have a Palliative Performance status of 50% or greater. By the time that the program discontinued, 366 patients had successfully completed the 8-week program. Pilot data acquired and compiled in 2013 revealed that with interdisciplinary palliative rehabilitation, patients reported improvements in physical function (increased endurance, mobility, balance, and decreased fatigue), nutrition, severity of burden of multiple symptoms, and reduced symptom interference in several domains of daily life (mood, enjoyment, general activity, and work). Patients did not report improvements in pain, shortness of breath, or mental fatigue. Longitudinal follow-up revealed that, despite indications of progressing neoplastic disease, many of the gains reported earlier were maintained. These included reduced symptom interference with walking, enjoyment in life, as well as improvements in nutrition, and reported “anxiety.” The approach of the PRP team is one of empowerment and emphasis on personal capability, bolstering the patients’ perception of their ability to deal with the multiple stressors faced (i.e., general self-efficacy), which are inherent in the challenging experience of living with advanced cancer.

Palliative care programs should be expanded to include formal exercise and nutrition components. From the point of diagnosis, patients with advanced cancer should have access to palliative care. Further research is needed to determine whether rehabilitation will improve survival in patients with advanced cancer although the primary focus of concern is substantial and meaningful improvement of QoL.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree