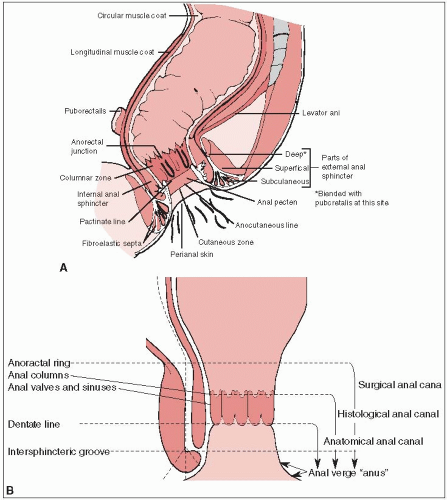

The anal canal is approximately 3 to 4 cm long, and extends from the level of the pelvic floor to the anal verge. The posterior wall is longer than the anterior.

The superior margin is determined clinically by the palpable upper border of the anal sphincter and puborectalis muscle of the anorectal ring. The distal end of the canal at the anal verge approximates the palpable groove between the lower edge of the internal sphincter and the subcutaneous part of the external sphincter (Fig. 29-1). The American Joint Committee on Cancer (3) and the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer recommend this definition of the anal canal rather than one used by some centers, in which carcinomas that arise above or exactly astride the dentate line are classified as anal canal tumors and those lying mainly or entirely below that line are called anal margin tumors.

Perianal carcinomas are arbitrarily considered to be cancers arising from the skin within a 5- to 6-cm radius of the anal verge.

The major lymphatic pathways drain to three lymph node systems. The perianal skin, anal verge, and canal distal to the dentate line drain predominantly to the superficial inguinal nodes, with some communications to the femoral nodes, and to the external iliac system. Lymphatics from around and above the dentate line flow with those from the distal rectum to the internal pudendal, hypogastric, and obturator nodes of the internal iliac system. The proximal canal drains to the perirectal and superior hemorrhoidal lymph nodes of the inferior mesenteric system.

There are many lymphatic connections between the various levels of the anal canal; an intramural system connects the lymphatics of the anal canal to those of the rectum (7).

Multivariate analyses in women demonstrated a far greater risk for anal cancer in patients with ten or more lifetime sexual partners (relative risk [RR] = 4.5); a history of anal warts (RR = 11.7), genital warts (RR = 4.6), gonorrhea (RR = 3.3), cervical dysplasia (RR = 2.3), prior testing for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (RR = 1.7), a known history of a sexually transmitted disease in sexual partners (RR = 2.4), or engaging in anal receptive intercourse before the age of 30 (RR = 3.4) or with multiple partners (RR = 2.5) (13).

Human papillomavirus (HPV) was present in 88% of the tumors from 394 patients with anal cancer; HPV was absent in 20 of the tumors from patients with rectal adenocarcinoma (13). Interestingly, 73% of the anal cancer patients with HPV detected in their tumors had HPV-16, the same strain as linked to the development of cervical cancer.

Squamous cancers of the anal canal spread most commonly by direct extension and lymphatic pathways. Hematogenous metastases are less common.

Direct invasion from the anal mucosa into the sphincter muscles and perianal connective tissue spaces occurs early; cancers were confined to the mucosa at diagnosis in only 12% of patients in one large series (5). In approximately half of the cases, these cancers extend into the rectum and/or perianal skin (11).

Invasion of the vaginal septum and mucosa is more common than invasion of the prostate gland.

Extensive tumors may infiltrate the sacrum and the coccyx or the pelvic side walls.

Lymphatic invasion occurs relatively early. Pelvic lymph node metastases are found in approximately 30% of patients treated by abdominoperineal resection. Lymphatic metastases increase in frequency with progressive enlargement of the primary cancer (5).

In one series, metastases were present in the superior hemorrhoidal nodes in 25% (15 of 61); in the external iliac, obturator, or hypogastric nodes in 30% (8 of 27); and in the inguinal nodes in 16% (12 of 74) of patients with epidermoid carcinomas of the anal canal (30).

Inguinal metastases are clinically detectable in approximately 20% of patients at the time of initial diagnosis and are usually unilateral.

Nodal metastases are seen in 30% of superficial tumors and 63% of deeply infiltrating or poorly differentiated tumors (7, 10).

Extrapelvic visceral metastases are identified at the time of presentation in approximately 10% of patients and are found most frequently in the liver and the lungs.

Bleeding and anal discomfort are the most common symptoms (reported by 50% of patients); other complaints include awareness of an anal mass, pruritus, anal discharge, and less frequently pain.

With proximal anal canal tumors, there may be an alteration in bowel habits, but this symptom is unusual with distal carcinomas.

Occasionally, asymptomatic tumors are found during physical examination, and unsuspected microinvasive carcinoma is sometimes found in mucosa removed at hemorrhoidectomy.

Gross fecal incontinence resulting from sphincter destruction occurs in less than 5% of patients, although some fecal soiling is common.

Synchronous inguinal node metastases are found in approximately 20% of patients.

The history and physical examination should stress features that delineate the extent of the primary tumor, including anal sphincter competence (Table 29-1).

A biopsy of the primary tumor is necessary to establish the diagnosis and the histologic type.

General anesthesia may be needed to permit detailed pelvic and anorectal examination, which should include proctoscopy and sigmoidoscopy.

Because lymph node enlargement may be caused by reactive hyperplasia in as many as half of those with palpable inguinal nodes, clinically suspicious nodes should be assessed by needle biopsy or simple excision (7, 10).

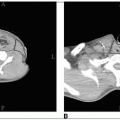

Transanorectal ultrasonography may help to identify the depth of tumor penetration into the anal wall (17).

Metastases in the internal iliac and superior hemorrhoidal nodes cannot be identified reliably by lymphangiography, pelvic lymphoscintigraphy, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging.

A chest film is sufficient screening for pulmonary metastases.

Abdominal and pelvic computed tomography scans are useful to outline the tumor and identify liver metastases or enlarged node masses that may be accessible to image-guided aspiration biopsy, in addition to localizing the kidneys when radiation therapy is to be used.

Skeletal studies are not indicated if there are no focal symptoms.

Full blood count, renal and liver function tests, and, if there are any risk factors present, assessment of HIV antibody status are routine tests (7).

TABLE 29-1 Diagnostic Workup for Cancer of the Anal Canal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

With the emergence of treatment strategies designed to preserve anorectal function, staging systems based on surgicopathologic parameters have been replaced by clinical staging systems.

The system most commonly used is that proposed by the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer and American Joint Committee on Cancer (Table 29-2) (3).

The World Health Organization pathologic classification is the most commonly used (19).

Squamous cell carcinomas (cloacogenic carcinomas), representing approximately 80% of all malignant tumors of the anal canal, are subdivided into large cell keratinizing, large cell nonkeratinizing, and basaloid.

Some nonkeratinizing tumors resemble transitional cell cancers of the urinary bladder.

Approximately 70% of squamous cell cancers are keratinizing or nonkeratinizing, and 30% are basaloid.

Mucoepidermoid cancers are rare.

The remaining cancers arising in the canal include adenocarcinomas of rectal type or from anal glands or fistulas, small cell cancers, and undifferentiated cancers.

TABLE 29-2 Classification and Staging of Carcinoma of the Anal Canal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||