Introduction

Elderly surgical patients present a specific challenge to anaesthesiologists and may be at greater risk of an adverse outcome.1 This is accounted for by a reduced ability to maintain or restore physiological homeostasis in the face of surgical and medical disease. This is exacerbated further by the presence of medical comorbidity such as cardiac or pulmonary disease or diabetes mellitus.2 The statistical likelihood of having a coincident medical pathology increases with advancing years. The elderly have a higher rate of mortality associated with anaesthesia and surgery than their younger counterparts. Postoperative adverse events on the cardiac, pulmonary, renal and cerebral systems are the main concerns for older surgical patients at high risk. The very fact that the patient requires hospital admission for their surgery exposes them to risk, with familiar hazards including nosocomial infection, administration of the wrong drug and side effects of certain procedures and investigations. Elderly patients are more likely to experience an adverse event during their hospital stay. The reduction of iatrogenic injury is one of the stated aims of the World Health Organization.3

The elderly, in particular those older than 85 years, are the fastest growing segment of the European and North American populations.4 Accordingly, overall life expectancy and active life expectancy have increased.4 The number of older patients presenting for surgery and anaesthesia is increasing and should not be a bar to surgery.5 The complexity of surgical procedures is also expanding. In 2001, the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland called for this expansion to be recognized and incorporated into service provision. They also called for greater availability of 24 h recovery facilities, High Dependency Unit (HDU) and Intensive Therapy Unit (ITU) beds for these patients.6

The National Confidential Enquiry into Perioperative Deaths7 highlighted the importance of availability of high dependency and intensive care facilities for the safe care of older patients: ‘the decision to operate includes the commitment to provide appropriate supportive care’.

This chapter elaborates on some of the risks to the elderly patient during the perioperative period and how they may be managed in order to minimize postoperative morbidity and mortality in this vulnerable patient group.

Outcome of Surgery and Anaesthesia in the Elderly

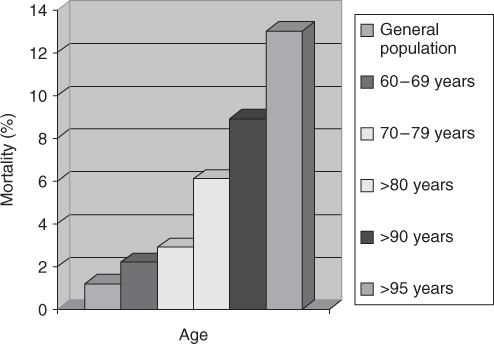

Mortality after surgery and anaesthesia is defined as the death rate within 30 days.7 The outcome of older patients from surgery, in general terms, has been studied by several groups in the past two decades,8–10 suggesting that healthcare practitioners have anecdotally identified areas for potential clinical improvement for many years. However, there are no recent surgical outcome studies for older patients. These early studies suggest that older patients have acceptable rates of perioperative mortality. There have been many advances in surgery and anaesthesia, such as laparoscopic surgery, ultra-short-acting anaesthetic medications, regional pain management and more extensive use of critical care services, over the past two decades, reducing mortality rates (Table 128.1, Figure 128.1). Higher mortality rates are associated with higher American Association of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade of physical status grade and emergency procedures.11 ASA is an independent predictor of mortality (Table 128.2). The highest risk surgical procedure in older patients is an exploratory laparotomy, because of the high risk of bowel infarction and disseminated carcinomatosis.

Table 128.1 Mortality associated with surgery and anaesthesia.

| Age (years) | Mortality rate (%) | Ref. |

| General population | 1.2 | 13 |

| 60–69 | 2.2 | 13 |

| 70–79 | 2.9 | 13 |

| >80 | 5.8–6.2 | 10 |

| >90 | 8.4 | 9 |

| >95 | 13 | 10 |

Table 128.2 ASA grading of physical status.11.

| Grade | Status |

| I | Normal healthy patient |

| II | Patient with mild systemic disease |

| III | Patient with severe systemic disease |

| IV | Patient with severe systemic disease which presents a constant threat to life |

| V | Moribund patient not expected to survive without operation |

Reproduced by permission of the American Society of Anaesthesiologists, Inc.

The presence of preoperative renal, liver and central nervous system impairment was a predictor of poorer outcome. Albumin, a marker of nutritional status, may serve as a surrogate marker for the preoperative health status of the surgical geriatric patient.12

Cardiovascular Morbidity Associated with Surgery and Anaesthesia

The age-related changes that occur within the cardiovascular system are responsible for the higher incidence of perioperative myocardial infarction, cardiac failure and arrhythmias in this age group. There is a reduction in the sensitivity of the parasympathetic system to changes in baroreceptor stretch, blood pressure and heart rate. The sensitivity of the sympathetic system also declines. This diminishes the body’s ability to compensate for sudden change. There is a progressive stiffening of both the arterial and venous vessels, again reducing capacity for vasoconstriction or dilatation in the face of loss of intravascular volume. Stiffening of the myocardium also occurs, affecting diastolic relaxation and filling pressures. This may lead on to diastolic dysfunction with an increase in left atrial pressure and pulmonary congestion.

Superimposed on physiological change, anaesthetic agents cause peripheral vasodilatation, with a decrease in systemic vascular resistance. As many elderly patients have a contracted intravascular volume secondary to diuretic therapy, this can mean a sudden fall in tissue perfusion pressure. Anaesthetic agents are myocardial depressants, particularly in higher doses, and have the capacity to affect cardiac output adversely. Preoperative assessment is focused on identifying those risk factors that have been identified in studies as being predictive of adverse postoperative outcome (Table 128.3).13, 14 Following the initial interview, the patient’s baseline level of function is assessed. If there are no significant predictors in the history, evaluation may be safely confined to detailed physical examination and a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). The ECG will identify patients with left ventricular hypertrophy or ST segment depression. These patients may require further investigation with an exercise ECG, depending on the surgical procedure planned. Determination of the anaerobic threshold for each patient using cardiopulmonary exercise testing is now considered a sensitive tool for determining patients at high risk.15 Patients who cannot exercise because of claudication or arthritis may be assessed with a dobutamine stress echocardiograph. Coronary angiography is reserved for patients with angina at rest or unstable angina. On the basis of the results, preoperative revascularization may be warranted. Clinically detected cardiac murmurs and features of congestive cardiac failure are further evaluated using echocardiography.

Table 128.3 Predictive factors for postoperative cardiovascular morbidity.

| Myocardial infarction within previous 3 months |

| Decompensated congestive cardiac failure |

| Arrhythmia (except premature atrial contractions) |

| Unstable angina or angina at rest (New York Heart Association Grade IV) |

| Uncontrolled hypertension |

| Severe valvular disease |

| Poor general medical condition |

| Poor exercise capacity |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| History of stroke |

Preoperative valve replacement is indicated for patients with severe disease. Less severe valve lesions or those following valve surgery require prophylactic antibiotic administration. Arrhythmia detected at rest or during exercise should be treated if possible before surgery. If sinus rhythm is not achieved, rate control with anticoagulation is acceptable. Type II or type III heart block requires insertion of a temporary or permanent pacemaker. Using the information gained from the history, examination and further investigations, the anaesthetic management is aimed at maximizing myocardial perfusion through maintenance of tissue perfusion pressure and oxygenation throughout the intra- and postoperative period. Postoperative admission to the HDU or intensive care unit (ICU) should be anticipated for elderly patients with significant cardiac symptoms, especially those undergoing abdominal or thoracic procedures. Invasive monitoring of blood pressure and central venous pressure is commenced early and continued throughout the perioperative period. Regional anaesthesia provides superior analgesia postoperatively and may reduce the incidence of adverse cardiac events in certain patients, such as vascular and abdominal surgery. The institution of perioperative β-receptor blockade has been shown to reduce the risk of myocardial ischaemia and is generally well tolerated by older patients.16 β-Blockade is thought to increase the time spent in diastole, increasing filling and increasing time for coronary artery perfusion. A combination of intravenous fluid infusion and vasopressor agents is used to maintain mean arterial blood pressure within 20% of the patient’s baseline, awake blood pressure. Episodes of hypotension must be managed promptly and oxygenation increased during the period of reduced flow.

Postoperatively, the patient requires a similar level of care and monitoring. Supplemental oxygen therapy, optimum analgesia, rate control and judicious blood transfusion will assist in maximizing myocardial oxygen supply. Particular attention should focus on the first 3 days, when myocardial infarction is most likely to occur. Many episodes of ischaemia in this age group may be silent and may not be associated with the development of Q waves on the ECG. A low index of suspicion, the presence of new ST changes, in combination with serial estimations of serum troponin T and I concentrations, will assist in early diagnosis.

Respiratory Morbidity Associated with Surgery and Anaesthesia

The physiological changes associated with ageing predispose the older patient to respiratory complications after surgery and anaesthesia. A mixed obstructive–restrictive pattern develops from the decrease in total lung capacity, elastic recoil of the thorax, pulmonary parenchymal compliance and vital capacity. Decreased compliance and muscle power mean a fall in forced expiration and a reduced capacity to cough and clear secretions. Closing capacity, dead space and residual volume increase so that the lungs of the supine patient become atelectatic. These changes do not occur in a uniform manner throughout the lungs, resulting in areas of good ventilation in combination with underventilated segments. A decrease in pulmonary blood flow combined with progressive loss of alveolar surface area diminishes the resting arterial oxygen tension from 95 ± 2 mmHg at age 20 years to 73 ± 5 mmHg at age 75 years. Occurring in tandem, there is an age-associated loss of central nervous system sensitivity to changes in arterial oxygen and carbon dioxide tensions. The physiological and structural changes cause an increase in ventilation–perfusion mismatch. This is exacerbated by the effect of anaesthesia, in particular, general anaesthesia. In addition, general anaesthesia reduces reflex pulmonary hypoxic vasoconstriction. Regional anaesthesia impacts less on the respiratory system as it does not necessitate intubation of the trachea, avoids the effect of intermittent positive pressure ventilation and provides highly effective postoperative pain relief.

Preoperative preparation of the patient involves a detailed history and examination in combination with functional assessment. Taking the patient for a walk, including two flights of stairs, during the preoperative visit provides a useful measure of the patient’s baseline physiological status. Smoking cessation for at least 8 weeks is to be recommended.17 Chest physiotherapy in the 24 h preceding surgery provides some physical benefit and facilitates instruction for deep breathing and coughing postoperatively. Patients with active pulmonary infection require more postponement of surgery and more aggressive medical treatment. The anaesthetic technique should employ regional analgesia/anaesthesia where possible. Short-acting agents such as propofol, remifentanil, sevoflurane and atracurium are most suitable for general anaesthesia. Muscle relaxants should always be reversed at the end of the procedure. Invasive monitoring may be used to advantage to guide fluid therapy as the older patient will tolerate rapid expansion of intravascular and extravascular volumes poorly due to the changes in pulmonary compliance, perfusion and renal function. This may be continued into the postoperative period in the context of ICU or HDU admission. Postoperatively, oxygen supplementation and chest physiotherapy should be continued for a minimum of 5 days as this is the greatest period of risk of nocturnal hypoxia and the onset of pneumonia.

Central Nervous System Morbidity Associated with Surgery and Anaesthesia

Elderly patients are at risk of serious central nervous system morbidity and mortality due to neuronal loss associated with ageing, the presence of coincident pathology such as cerebrovascular atherosclerosis and a reduction in neurotransmitter concentrations. This makes them less able to adapt successfully to the challenges imposed by surgery and anaesthesia. The morbidity associated with anaesthesia and surgery in the older patient most commonly takes the form of postoperative confusion (POC) or stroke.

Postoperative Confusion

The risk factors for the development of POC are listed in Table 128.4. POC is associated with an increased rate of morbidity, delayed return to baseline function and delayed discharge home from hospital. To date, there is little evidence for an overall strategy to reduce the incidence in surgical patients, but some general recommendations may be made.

Table 128.4 Risk factors for the development of postoperative confusion.

| Preoperative factors |

| Older age |

| Depression/anxiety |

| Dementia |

| Preoperative sensory deficit in hearing or vision |

| Alcohol withdrawal/sedative withdrawal |

| Preoperative use of multiple medications |

| Intraoperative factors |

| Hypoxia |

| Hypocarbia |

| Hypotension |

| Postoperative factors |

| Inadequate analgesia |

| Perioperative factors |

| Sepsis |

| Surgical procedure |

| Cardiac surgery |

| Orthopaedic surgery, especially joint replacement |

| Perioperative medications |

| Anticholinergics: atropine, scopolamine. Glycopyrrolate to a lesser extent |

| Barbiturates |

| Benzodiazepines |

| Antihistamines |

Consideration should be given to admitting the patient as a daycase, as elderly patients become less disorientated when in familiar surroundings with familiar carers. The preoperative assessment should highlight particular issues that could be modified or pre-empted, such as alcohol withdrawal depression. Hearing aids and spectacles should be left with the patient until induction of anaesthesia and returned to the patient as soon as possible. Medications listed in Table 128.3 should be avoided. Intraoperative monitoring of blood pressure, ventilation and oxygenation requires a meticulous approach.

Hypoxaemia and hypercarbia should be avoided. The minimum number of medications possible should be employed. Regional analgesic techniques should be employed where possible to reduce the use of sedating narcotics in the postoperative period. There is no difference in the incidence of POC between the intraoperative use of general anaesthesia and spinal or epidural anaesthesia.18 A geriatrician should be involved in the care of the patient at high risk of confusion. Postoperatively, if the patient is confused, they should be nursed in a quiet, dark room. Organic causes should be treated promptly. Haloperidol 0.25–2 mg orally at night may be useful. Low doses of diazepam or chlorpromazine may be used as adjuncts if the patient does not respond to simple measures. Physical restraints usually serve to antagonize the patient further and should not be used. Referral to the occupational therapy and social work departments will be necessary to assist with cognitive assessment, follow-up and discharge planning.

Long-term cognitive impairment has been documented by the International Study of Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction (ISPOCD).19 About 10% of patients were found to have cognitive deficits 3 months after surgery, with age as the only significant predictive factor.

Postoperative Stroke

There have been few studies to determine the incidence of stroke occurring after surgery and anaesthesia. The incidence from small retrospective studies seem to suggest that the incidence is low, in the order of 0.25% when a patient is undergoing non-carotid vascular surgery.20 Stroke most commonly occurs between days 5 and 26 postoperatively. Risk factors for postoperative stroke are given in Table 128.5.21

Table 128.5 Risk factors for postoperative stroke in the elderly.

| Preoperative factors |

| Pre-existing cerebrovascular disease |

| Ischaemic cardiac disease |

| Atherosclerosis |

| Carotid occlusion |

| Preoperative vascular disease |

| Hypertension |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Physical inactivity |