Evidence From Studies

In a cross-sectional population based study,1 better global cognitive functioning assessed through psychometric tests such as the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) was associated with moderate wine consumption [odds ratio (OR) = 0.62; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.48–0.81; p = 0.0004]. This association disappeared, however, when controlled for age, gender, educational level and occupational category, showing that confounding is a major issue in the study of alcohol consumption. Prospective studies also analysed the association between alcohol consumption and cognitive decline. A subsample of 387 survivors of 1083 subjects recruited between 1983 and 1985 in the cognitive substudy of the Medical Research Council treatment trial of hypertension was examined 9–12 years after the initial visit to assess cognition.2 Poorer cognitive outcome was associated with abstinence from alcohol prior the age of 60 years.

In a randomly selected sample of 333 men living in Zutphen, The Netherlands, and followed for 8 years, low-to-moderate alcohol intake had a significantly lower risk for poor cognitive function (MMSE < 25) than abstainers (OR of 0.3 for less than one drink and 0.2 for one to two drinks per day).3 However, alcohol intake was not associated with cognitive decline. In women, alcohol consumption was also shown to be associated with a reduced risk of cognitive decline. Data from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study of postmenopausal combination hormone therapy were used to assess cross-sectional and prospective associations of self-reported alcohol intake with cognitive function.4 Compared with no intake, intake of ≥1 drink per day was associated with higher baseline modified MMSE scores (p < 0.001) and a covariate-adjusted OR of 0.40 (95% CI, 0.28–0.99) for significant decline in cognitive function over 3 years. Associations with incident probable dementia were of similar magnitude but were not statistically significant after covariate adjustment.

In the MoVIES project, cognitive functions and self-reported drinking habits were assessed at 2 year intervals over an average of 7 years of follow-up.5 Trajectory analyses identified latent homogeneous groups with respect to frequency of alcohol use over time and their association with average decline over the same period in each cognitive domain. Three homogeneous trajectories were defined and were characterized as no drinking, minimal drinking and moderate drinking. Compared with no drinking, minimal drinking was associated with lesser decline on the MMSE (OR = 0.05; 95% CI, 0.01–0.26) and Trail Making Tests (OR = 0.02; 95% CI, 0.001–0.22), that evaluated executive functions. The same trends were observed for moderate drinking (MMSE, OR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.09–0.84; Trail Making Test, OR = 0.15; 95% CI, 0.03–0.79). Minimal drinking was also associated with lesser decline in tests of learning and naming. These associations did not change on comparing current drinkers with former drinkers (quitters) and with lifelong abstainers.

Prospective Evidence

The first prospective study to explore the association between alcohol intake and dementia was the PAQUID programme.6 A sample of 3777 subjects aged 65 years or older was followed for 3 years and 99 incident cases of dementia were diagnosed. Alcohol consumption data were collected at baseline, with wine being the main type of alcohol consumed, usually on a daily basis. Four categories of individuals were defined: non-drinkers, mild drinkers (consuming up to 0.25 l of wine, i.e. two drinks per day), moderate drinkers (consuming up to 0.5 l of wine, i.e. three to four drinks per day) and heavy drinkers (consuming more than four drinks per day). Lower risks of developing dementia were found among drinkers compared with non-drinkers, but the relationship was significant only for moderate drinkers [mild drinkers, risk ratio (RR) = 0.81; moderate drinkers, RR = 0.19; heavy drinkers, RR = 0.31]. No modification effect was found according to gender and the association did not change after adjusting for age, gender, education, occupation and baseline cognition. After 10 years of follow-up, the association between baseline alcohol consumption and incident dementia remained significant, although the risk ratios tended to increase toward unity (mild drinkers, RR = 0.89, 95% CI, 0.70–1.15; moderate drinkers, RR = 0.56; 95% CI, 0.36–0.92).7

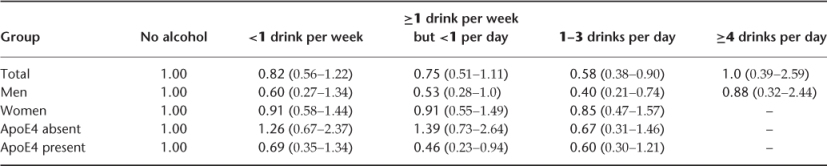

The Rotterdam Study followed 5395 subjects aged 55 years or older over a period of 6 years; 197 incidents cases of dementia were diagnosed.8 The number of drinks of alcohol (beer, wine, fortified wine or spirits) was collected at baseline and five categories of intake were studied: no drinks consumed; less than one drink per week; more than one drink per week but less than one per day; one to three drinks per day; more than three drinks per day. The risk of developing dementia was lower among drinkers compared with non-drinkers (Table 120.1) and was significant in the 1–3 drinks per day category. The pattern was different in men and women. No association was found in women, whereas a lower risk was found for men drinking 1–3 drinks per day. A modification effect was found when the apolipoprotein E4 allele (ApoE4) was taken into consideration: the risk was lower among drinkers with an ApoE4 allele, whereas it was less clear for drinkers without the ApoE4 allele (Table 120.1). No difference was found according to beverage type, although beer tended to give marginally lower risk than wine.

Table 120.1 Hazard ratios (with 95% CI) of dementia according to alcohol consumption in the Rotterdam Study.

In a prospective study of elderly people living in North Manhattan,9

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree