ADRENAL CORTEX AND PREGNANCY

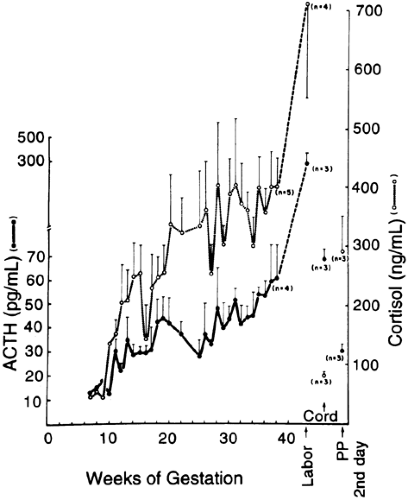

Cortisol levels rise progressively over the course of gestation, resulting in a two- to three-fold increase by term100 (Fig. 110-5). Most of the elevation of cortisol levels is due to the estrogen-induced increase in cortisol-binding globulin levels,101 but the bioactive “free” fraction also is elevated three-fold and the cortisol production rate is increased.100,101 This is reflected in two-to three-fold elevations in urinary free cortisol levels.100,101

ACTH levels have been variously reported as being normal, suppressed, or elevated early in gestation.100,102 During pregnancy, a progressive rise is seen, followed by a final surge of ACTH and cortisol levels during labor.100 ACTH does not cross the placenta but is manufactured by the placenta.102 The amounts of ACTH in serum that are of placental as compared to pituitary origin at various stages of gestation are not known. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is also produced by the placenta and is released into maternal plasma.103 The CRH is bioactive and may release ACTH both from the placenta, in a paracrine fashion, and from the maternal pituitary103 (although the latter source is not absolutely proven).

CUSHING SYNDROME DURING PREGNANCY

Just under 100 cases of Cushing syndrome in pregnancy have been reported.104,105,106,107,108,109 and 110 The distribution of causes in pregnant women differs from that in the nonpregnant population. Less than 50% of the patients described had pituitary adenomas, a similar number had adrenal adenomas, and 10% had adrenal carcinomas.104,105,106,107,108,109 and 110 Only one report described a pregnancy associated with the ectopic ACTH syndrome.106 In many cases, the hypercortisolism first became apparent during pregnancy, with improvement after parturition; this leads to the speculation that unregulated placental CRH was instrumental in causing this pregnancy-induced exacerbation.105,106

Diagnosing Cushing syndrome during pregnancy may be difficult. Both conditions may be associated with

weight gain in a central distribution, fatigue, edema, emotional upset, glucose intolerance, and hypertension. The striae associated with the weight gain and increased abdominal girth are usually white in normal pregnancy and red or purple in Cushing syndrome. Hirsutism and acne may point to excessive androgen production.

weight gain in a central distribution, fatigue, edema, emotional upset, glucose intolerance, and hypertension. The striae associated with the weight gain and increased abdominal girth are usually white in normal pregnancy and red or purple in Cushing syndrome. Hirsutism and acne may point to excessive androgen production.

The laboratory evaluation of Cushing syndrome during pregnancy is not straightforward. Elevated total and free serum cortisol and ACTH levels, and urinary free cortisol excretion are compatible with that of normal pregnancy. The overnight dexa-methasone test usually demonstrates inadequate suppression during normal pregnancy.107 At least in the latter part of the third trimester, the elevated cortisol levels are not suppressed during the low-dose dexamethasone test but are suppressed during the high-dose test, as in patients with Cushing disease.108 ACTH levels are normal to elevated in pregnant patients with all forms of Cushing syndrome.104,105,106,107,108,109 and 110 These “normal” rather than suppressed levels of ACTH in patients with adrenal adenomas may result from the production of ACTH by the placenta or from the nonsuppressible stimulation of pituitary ACTH by placental CRH.

A persistent circadian variation in the elevated levels of total and free serum cortisol during normal pregnancy may be most helpful in distinguishing Cushing syndrome from the hyper-cortisolism of pregnancy, because this finding is characteristically absent in all forms of Cushing syndrome.101 In many cases, radiologic imaging is necessary. An adrenal mass often is visible with ultrasonography; however, CT or MRI scanning of the pituitary or adrenal may be required. Most adrenal lesions are unilateral, so that localization is important. Little experience has been reported with newer techniques such as CRH stimulation testing or petrosal venous sinus sampling during pregnancy (see Chap. 75). However, in a case study, a woman with Cushing disease who had the typical exaggerated ACTH response to CRH experienced no ill effects from such testing.108 CRH testing during petrosal sinus sampling was performed without ill effects in a woman at 14 weeks’ gestation, but catheterization was performed via the direct internal jugular vein approach rather than the femoral vein approach to minimize fetal irradiation.111

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree