Abnormalities of the Breast in Pregnancy and Lactation

Richard B. Wait

Holly S. Mason

Breast disease during pregnancy and lactation can represent a clinical and diagnostic dilemma for the clinician due to the significant change to the breast parenchyma from hormone-related hypertrophy and increased vascularity. These changes affect the clinical breast examination as well as alter the efficacy of the currently available imaging modalities. Added to this is the need to balance concern for the mother with concern for the fetus. Breast cancer remains one of the most common types of cancer to be diagnosed during pregnancy or in the lactational period (1) (see Chapter 67); benign breast disease, however, is even more prevalent during this period. It is critical for the physician to remain as diligent in the evaluation of any breast abnormality in the pregnant or lactating patient as one would in any other woman. This chapter reviews the current state of the diagnosis and treatment of benign breast disease during pregnancy and lactation.

EVALUATION

Clinical Breast Examination

During the course of pregnancy, pregnancy-related hormones (estrogen, progesterone, and prolactin) cause breast tissue to undergo significant changes that lead to increased volume and density (see Chapter 1). During the first trimester, the ratio of fatty tissue to glandular tissue decreases; as the volume of glandular tissue increases, so does the overall volume of the breast. As the pregnancy progresses, these changes intensify and make the evaluation of any breast abnormality more difficult. It is preferred, therefore, for the pregnant patient to have a baseline clinical breast examination during the first trimester before these changes have occurred. As the number of women who become pregnant during their fourth decade increases, it is likely that more women will present already having had a baseline mammogram before becoming pregnant. A prior mammogram and any other imaging study obtained before pregnancy may help facilitate the evaluation of a new mass.

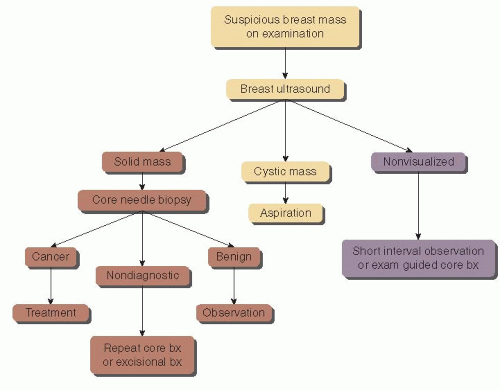

The pregnant patient who presents with a new mass or physical finding should be evaluated and followed very closely. If observation is chosen after completion of the appropriate workup (described later in this chapter), a short interval follow-up examination is indicated because delay in examination may allow pregnancy-related changes (such as an increase in volume or nodularity) to obscure the physical finding. Because the pregnant patient does not undergo the cyclic hormonal changes that the nonpregnant patient experiences, persistence of a mass after a short interval warrants further attention (Fig. 7-1). Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the clinician who identifies a breast mass to rule out a pregnancy-associated breast cancer.

Diagnostic Imaging Issues in Pregnancy and Lactation

When evaluating a pregnant patient, consideration must be given to minimizing exposure of ionizing radiation to the fetus. For this reason, ultrasonography is an ideal first option in the evaluation of a breast mass in this patient population. Ultrasound is a reliable means of differentiating a fluid-filled structure (cyst) versus a solid mass. It can assess the margins and shape of a solid mass or identify shadowing, which may help differentiate a benign mass (e.g., lymph node or adenoma) from a malignancy. Ultrasound can easily guide aspiration of a cyst or percutaneous biopsy of a suspicious mass. An important benefit of ultrasound is that it is less affected by pregnancy-related changes than is mammography. Ultrasound can have 100% sensitivity for identifying malignancy as seen in multiple studies, and high specificity rates are seen as well (Table 7-1). For these reasons, ultrasound is the optimal first imaging study employed for a pregnancy-related breast mass.

The use of mammography in this patient population, on the other hand, remains controversial. There is concern over the potential for exposure of the fetus to ionizing radiation but, with proper abdominal shielding, exposure to the fetus is considered negligible (5). A second issue affecting the use of mammography, however, is the potential for lowered sensitivity owing to the increased density of the pregnant breast and the decrease in adipose tissue-to-breast parenchyma ratio (6), although this is not universally seen

(3, 7). Yang et al. (2) documented that a malignancy was visualized in 18 of 20 patients (90%) with breast cancer despite the breast density issue. The lactating patient can improve the quality of the mammographic study by emptying her breast either by nursing or pumping immediately prior to the study. In general, mammography should not be the primary imaging tool if there is a suspicious physical examination finding in a pregnant patient. If a patient has a suspicious discrete mass on examination that is not visible on ultrasound, tissue diagnosis with percutaneous biopsy can be performed. Mammography is more useful in the lactating patient or in the newly diagnosed pregnant patient to assess for calcifications or extent of disease.

(3, 7). Yang et al. (2) documented that a malignancy was visualized in 18 of 20 patients (90%) with breast cancer despite the breast density issue. The lactating patient can improve the quality of the mammographic study by emptying her breast either by nursing or pumping immediately prior to the study. In general, mammography should not be the primary imaging tool if there is a suspicious physical examination finding in a pregnant patient. If a patient has a suspicious discrete mass on examination that is not visible on ultrasound, tissue diagnosis with percutaneous biopsy can be performed. Mammography is more useful in the lactating patient or in the newly diagnosed pregnant patient to assess for calcifications or extent of disease.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the breast has been used increasingly in the evaluation and treatment of breast cancer. At this time, however, it has not been well studied in the pregnant patient. Pregnancy-associated changes alter the ratio of parenchyma to adipose tissue, causing increased flow and permeability (8). In addition, gadolinium (the contrast agent used in breast MRI) crosses the placenta and, therefore, is a pregnancy category C drug.

TABLE 7-1 Sensitivity and Specificity of Ultrasonography and Mammography in Pregnant Women or Lactating Women | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

It is advised to wait until after first trimester if breast MRI is judged to be absolutely necessary (9). Gadolinium uptake in lactating breast tissue can mimic malignancy, however, and result in a false-positive study result (8). MRI is currently not indicated in the pregnant or lactating patient for these reasons.

Tissue Biopsy in the Pregnant and Lactating Patient

Percutaneous biopsy has become the standard of care for tissue diagnosis of any breast mass or imaging abnormality in any patient. Surgical incisional or excisional biopsy for diagnosis necessitates an incision and there is a potential need to return for additional surgery if the biopsy reveals malignancy. Each operation contains risks to both the patient and the fetus that should be minimized if possible. Thus, the clinician must protect the fetus while ensuring appropriate treatment for the patient. A secondary benefit to percutaneous biopsy over surgery for diagnosis should be minimal disruption of the ductal structures of the breast

to facilitate successful lactation. An in-depth discussion of the risks and benefits of biopsy needs to be held with the patient to allow for informed consent.

to facilitate successful lactation. An in-depth discussion of the risks and benefits of biopsy needs to be held with the patient to allow for informed consent.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree