Chapter 73 Abnormalities of Fat Distribution in HIV Infection

Shortly after the introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy with HIV protease inhibitors (PIs), changes in fat (Table 73-1) and serum metabolites were seen that were attributed to PI drugs. In 1997, three early case reports described phenomena such as hypertrophy of the breasts and upper chest fat accompanied by enlargement of the abdomen and thinning of the buttocks and legs,1 benign symmetric lipomatosis,2 and loss of subcutaneous fat.3 At the same time, papers describing dyslipidemia,4 hyperglycemia, and eventually insulin resistance5,6 that were attributed to PI therapy were published. The next manifestation was the appearance of ‘buffalo hump’, a fat pad on the upper back, between the shoulders, often extending to the neck.7–9 Increased abdominal size with increased visceral (intra-abdominal) fat was also reported.10 Shortly thereafter, a flood of reports were published of fat loss in the periphery (face, legs, and arms) and gain of fat centrally.11

Table 73-1 Fat Distribution Changes Reported in HIV Infection in the Era of Combination Antiretroviral Therapy

| Reported Finding | Description | Current Status |

|---|---|---|

| Buffalo hump | Increased fat in between the scapula, going up the neck | A result of lipoatrophy being more severe in the lower body. With weight gain, more fat is put on upper trunk and neck |

| Peripheral lipoatrophy | Loss of fat in legs and face | Now recognized to be subcutaneous lipoatrophy with legs more affected than upper trunk |

| Visceral obesity | Increased fat within the abdomen | Unrelated to lipoatrophy |

| Central lipohypertrophy | Increased fat in abdomen and trunk | Visceral obesity as above. In most patients central subcutaneous fat is reduced. With gain in fat, it is disproportionately placed in the upper trunk |

| Breast enlargement | Increased fat in breast | A result of subcutaneous lipoatrophy and weight gain, as above |

| Lipomatosis | Multiple fat tumors | A rare presentation. Relation to HIV unclear |

The striking loss of fat in the face became the new stigma of HIV. It ‘outed’ patients who were now healthy and no longer had wasting or Kaposi sarcoma to identify them as HIV-infected.12 The presence of lipoatrophy greatly decreases quality of life at a time of restoration to health.13–15 Indeed, some patients stopped antiretroviral therapy in the hope of reversing the changes.16

The combination of hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and abdominal obesity was evocative of the metabolic syndrome, which predicts increased risk of cardiovascular disease. The findings were rapidly synthesized into a single syndrome called HIV-lipodystrophy or fat redistribution syndrome which coupled peripheral fat loss to central fat gain, accompanied by insulin resistance and hyperlipdemia.17,18 The syndrome was proposed to be due to PI drugs.

The proposed syndrome neglected the abnormalities previously seen in patients with HIV infection, such as cachexia, low LDL and HDL, hypertriglyceridemia, and perhaps even increased sensitivity to insulin.19,20 As will be delineated in this chapter, it is now clear that many of these changes are not linked in a single syndrome (e.g., peripheral fat wasting is not associated with central fat gain). Subcutaneous lipo-atrophy at peripheral and central sites is the lesion most characteristic of HIV infection; the lower body is affected more than the upper body. There are multiple factors that may contribute to each change, rather than them all being due to PI therapy. The increase in visceral fat is not HIV-related. Finally, once lipoatrophy occurs, it is difficult to reverse.

ASSESSING CLINICAL SYNDROMES

A large number of reports on HIV lipodystrophy and its metabolic consequences relied on subjective criteria that differed among research groups.11,21 Four different descriptions were used: (1) both peripheral lipoatrophy and central lipohypertrophy; (2) either peripheral lipoatrophy or central lipohypertrophy; (3) only peripheral lipoatrophy; and (4) only central lipohypertrophy. There were at least four ascertainment methods, which were not quantitative and also varied among the reports: (1) self-report of change in fat; (2) exam finding of fat abnormalities; (3) self-report of change in fat confirmed by exam finding of fat abnormalities; and (4) review of charts for report of HIV lipodystrophy. Perhaps as a consequence of these techniques, the prevalence of the ‘HIV-lipodystrophy syndrome’ was reported to vary between 2% and 84%.11

More important, there were major disagreements over the cause of the ‘HIV-lipodystrophy syndrome’.11,21 Some blamed PI drugs, while others blamed NRTI drugs. Other factors proposed to contribute included HIV itself, diagnosis of AIDS, history of CD4 counts, and age. The fact that differing definitions were used for HIV lipodystrophy led to disagreement over what were the potential causal factors.

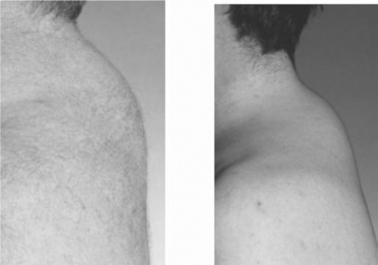

Buffalo Hump

The reports of buffalo hump in HIV infection were accompanied by photographs (Figure 73-1) of large fat depositsin the upper back, often wrapping around the neck and cervical fat pads.7–922 Many patients have difficulty sleeping on their backs due to the large fat deposits. Given that the majority of AIDS patients were wasted (cachectic) before the introduction of effective combination therapy, this change was striking. Furthermore buffalo hump appeared rapidly (over a few months) in some patients.

Buffalo hump is found in patients with Cushing syndrome due to glucocorticoid excess. The first reports of buffalo hump ruled out circulating glucocorticoid excess as the cause of buffalo hump in HIV infection.7,8 It is still possible that there is an indirect contribution of glucocorticoids to the appearance of buffalo hump, as upper body fat may convert more corticosterone to cortisol, the active glucocorticoid, leading to increased intracellular cortisol, promoting proliferation similar to that seen in Cushing syndrome.

In the earliest report of buffalo hump in HIV infection, half of the subjects were not on PI drugs.7 These data were unfortunately ignored as others pursued PI drugs as the cause of a pooled syndrome or lipohypertrophy.

Increased Abdominal Fat

The finding of increases in abdominal fat also seemed striking after years of having cachectic patients with HIV infection.10 This change was often called ‘Crix belly’, after Crixivan® (indinavir), one of the first effective PI drugs. It is not clear why this change was not initially linked to the use of ritonavir or saqunavir, but the gastrointestinal side effects of the early preparations and/or high doses of these drugs may have decreased weight gain.

CT and MRI imaging showed that many HIV-infected patients with large bellies had increased visceral adipose tissue (VAT),10 which is associated with metabolic abnormalities and increased risk of cardiovascular disease. It should be noted that a high percentage of the non-HIV-infected population in the industrialized world has obesity; some studies find that one-third are obese and another one-third are overweight.23 Several factors including age, race, and gender influence visceral obesity.24 Obesity progresses with age and age is the major determinant of increased VAT even in the absence of obesity. Men have more VAT than women. Caucasians are more susceptible to increased VAT.

Increased Breast Size

The initial reports of changes in fat in HIV-infected women, emphasized central obesity and, in particular, increases in breast size.1,25,26 In addition to pendulous breasts, large amounts of fat in the chest and upper back were reported. These findings paralleled the upper trunk fat seen in many patients with buffalo hump.

While the syndrome was described in women on PI, an early report found an association with lamivudine use.26 Given the small size of the seminal studies, it is difficult to assess the role of any drug or class of drugs that were commonly used and in particular to distinguish that from therapy per se.

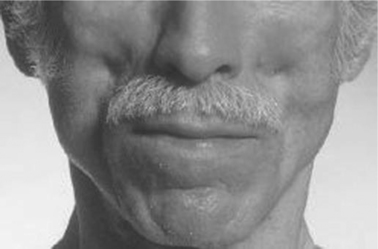

Peripheral Lipoatrophy

The most striking change reported was loss of subcutaneous fat in the peripheral sites of the face, legs, and arms.27 Some patients had virtually no facial fat in Bichat’s fat pad, the area of the cheeks below the eyes (see Figure 73-2). This change is not characteristic of other diseases with cachexia. Furthermore, the decrease in fat in the face, legs, and arms occurred when muscle mass was being restored due to effective therapy, a finding that is the antithesis of the cachexia seen for decades in patients with HIV infection. Veins and muscle appeared very prominent in affected arms and legs (see Figure 73-3). Careful examination of some of the photographs of HIV-infected patients with protuberant bellies revealed decreased subcutaneous fat in the abdomen.27

The first reports of peripheral lipoatrophy attributed it to PI drugs.3,17 However, soon thereafter a role for NRTI emerged. Reports appeared of HIV-infected patients with peripheral lipoatrophy who were only on NRTI drugs and had never taken a PI.28,29 Stavudine was more strongly linked to the presentation of peripheral lipoatrophy than any other NRTI. In the early days of PI therapy, not all patients were on NRTI combinations that are now deemed highly active; one analysis found that even among patients reported to have PI-associated fat distribution changes, those with lipoatrophy were twice as likely to be on stavudine and/or lamivudine (mostly on both in combination) than those with fat accumulation.30

WHAT IS THE HIV-ASSOCIATED SYNDROME OF LIPODYSTROPHY?

Peripheral Lipoatrophy Is Not Linked to Central Lipohypertrophy

In most early studies of HIV-lipodystrophy, entry was by clinical presentation, but measurement of fat was performed in some studies. Although many of the patients were clinically described as having increased abdominal fat (or girth), direct measurements of fat mass by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) revealed less truncal fat compared to those without the HIV-lipodystrophy syndrome.11,17 These measurements were the first indication that the clinical presentations might not accurately represent the actual findings. They also raised the question of ‘pseudo-truncal obesity’, where loss of fat in arms and legs made the abdomen look prominent.11

As discussed above, many of the clinical instruments used assumed that the syndrome was peripheral fat loss and central fat gain. The instruments were unidirectional, i.e., the studies only measured peripheral fat loss or looked for peripheral lipoatrophy; they did not consider peripheral fat gain. More importantly, the instruments measured the central gain and looked for central lipohypertrophy; they did not look for central fat loss. As a consequence, these studies were never able to determine whether there was a statistical association of peripheral lipoatrophy and central lipohypertrophy or whether central depots had lipoatrophy.

The study of Fat Redistribution and Metabolic Change in HIV Infection (FRAM), a large (1183 HIV-infected subjects and 297 controls), multicenter study included clinical instruments similar to other studies, as well as direct measurements of fat.31 However, the FRAM surveys of self-report of change in fat and examinations of fat were bidirectional. For example, subjects were asked about fat loss or fat gain in each body area. The FRAM study found that HIV-infected subjects reporting loss of fat in the periphery more often reported loss of or less gain of central fat than subjects not reporting peripheral fat loss.32,33 Subjects with abnormally low peripheral fat on examination had less central fat than those who did not have peripheral fat loss. Thus, even in the ‘clinical syndrome’, there was no indication that loss of peripheral fat was linked to gain of central fat, providing evidence against using those two findings as part of a single syndrome.

Mimicking many early studies, FRAM defined lipoatrophy as self-report of loss of fat in an anatomical area confirmed by abnormally less fat in that area on examination. Likewise, lipohypertrophy was defined as gain of fat in an anatomical area confirmed by abnormally more fat in that area on examination. Because bidirectional scales were used, it was possible to study lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy at both central and peripheral sites. Peripheral lipoatrophy was found in 38% of HIV-infected men and somewhat less frequently in HIV-infected women; the rates were less than 5% in controls.32,33 Central lipoatrophy was less common, but occurred more often in HIV-infected subjects than controls. Central lipohypertrophy was found in 40% of HIV-infected men and slightly more often in HIV-infected women. However, central lipohypertrophy was actually less frequent in HIV-infected men than control men, while the rates in HIV-infected and control women were similar. Peripheral lipohypertrophy was uncommon in HIV-infected subjects.

FRAM then determined the association among the potential clinical syndrome.32,33 Rather than finding a link between peripheral lipoatrophy and central lipohypertrophy, FRAM showed that the two findings were disassociated (for men the odds ratio of peripheral lipoatrophy occurring with central lipohypertrophy was OR = 0.7, CI = 0.47–1.1, P = 0.10; for women OR = 0.39, 95% C.I. = 0.20–0.75, P = 0.006). Thus, peripheral lipoatrophy and central lipohypertrophy could not be part of a single syndrome.

Measurements of Fat Prove Lipoatrophy and Lipohypertrophy Are Independent

The Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) asked subjects at sequential visits about change in fat and estimated amounts of fat by anthropometric measurements.34 They defined lipoatrophy as report of loss of fat accompanied by a decrease in fat measured by anthropometry. They defined lipohypertrophy as report of gain of fat accompanied by an increase by anthropometry. HIV-infected women in WIHS had more peripheral and central lipoatrophy than control women. HIV-infected women had less peripheral lipohypertrophy, than controls, but similar central lipohypertrophy. The authors concluded that lipoatrophy, in both peripheral and central sites, was the hallmark lesion in HIV infection; there was little evidence for excess central lipohypertrophy in HIV-infected women.34

In the Multi-center AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) anthropometric measurements were also performed in HIV-infected men and controls.35 In MACS, HIV-infected subjects had less fat than controls as estimated by anthropometrics in both peripheral and central sites. They concluded that HIV-infected men receiving HAART were characterized by lipoatrophy, not lipohypertrophy.35

The control group from MACS is from the same at-risk cohort and the controls groups in WIHS were recruited to be similar. In both WIHS and MACS, the control groups had a tendency to be heavier than equivalent age subjects in the NHANES study that is representative of the US population.34,35

The FRAM study performed whole-body MRI for body composition.31 Subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) volumes were measured in the peripheral sites of the leg and arm and the central sites of the abdomen/back and chest/back. VAT was also measured. There were no inverse relationships between peripheral adipose tissue depots and central adipose tissue depots.32,33 HIV-infected subjects with the clinical syndrome of peripheral lipoatrophy had less adipose tissue in both peripheral and central sites than HIV-infected subjects without the clinical syndrome of peripheral lipoatrophy. Within the group with peripheral lipoatrophy, there was a positive correlation between all peripheral and central sites (not an inverse correlation), although the correlation between leg and VAT was not statistically significant. The HIV-infected group without clinical peripheral lipoatrophy had lower leg SAT than controls, but similar VAT in men and increased VAT in women. Thus, the clinical syndrome underestimates the prevalence and amount of lipoatrophy. For both HIV-infected groups, leg SAT showed the greatest decrease compared to controls, while upper trunk showed the least decrease. Indeed, in HIV-infected women without the clinical syndrome of peripheral lipoatrophy (a group that had a higher body mass index (BMI)), chest and upper back fat was higher than controls.

All HIV-infected groups had ranges of VAT that were similar to the controls.32,33 Thus, there is a wide spectrum of HIV-infected patients with decreased leg SAT and some have increased VAT. However, there is no association of decreased leg SAT with increased VAT. The measurements of fat also demonstrate that there is no link between peripheral lipoatrophy and central lipohypertrophy. Rather, the abnormal syndrome in HIV infection is loss of subcutaneous fat in both peripheral and central depots, with lower sites affected more than upper sites. Increased VAT is not part of the syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree