THERAPY

Part of “CHAPTER 58 – PRIMARY HYPERPARATHYROIDISM“

SURGERY

In view of the modern clinical profile of primary hyperparathyroidism, not all patients have features that would prompt a recommendation for surgery. The existence of asymptomatic

patients with primary hyperparathyroidism has engendered controversy about the need for parathyroidectomy and surgical guidelines.

patients with primary hyperparathyroidism has engendered controversy about the need for parathyroidectomy and surgical guidelines.

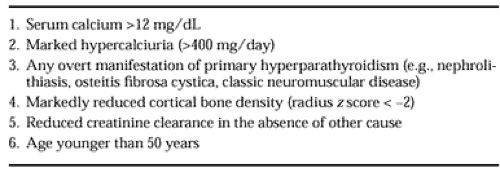

At the Consensus Development Conference on the Diagnosis and Management of Asymptomatic Primary Hyperparathyroidism, a set of surgical guidelines was endorsed73 (Table 58-1). The criteria for surgery include serum calcium concentration >12 mg/dL; any complication of primary hyperparathyroidism (e.g., overt bone disease, nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis, classic neuromuscular disease); marked hypercalciuria (>400 mg per day); reduction in bone density more than two standard deviations below normal at the site of cortical bone, as in the forearm; an episode of acute hyperparathyroidism; and age younger than 50 years (see Table 58-1). Approximately 50% of patients with primary hyperparathyroidism meet one or more of these criteria. This is a significantly greater percentage of patients that have symptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism (20–30%). Some patients with asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism do meet surgical criteria and are candidates for parathyroid surgery, and in individual cases, surgical guidelines may be altered according to clinical judgment.

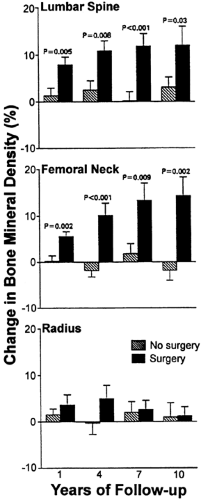

Parathyroidectomy leads to the rapid resolution of the biochemical abnormalities of primary hyperparathyroidism.74 Surgery has also been documented to be of clear benefit in reducing the incidence of recurrent nephrolithiasis75,76 and in leading to an improvement in bone mineral density.74 Parathyroidectomy leads to a 12% rise in bone density mainly at the cancellous lumbar spine and femoral neck (Fig. 58-5). This increase is sustained over at least four years after surgery.

A few patients show a densitometric profile that is unusual for patients with asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism. These individuals do not show the usual sparing of cancellous bone; rather, they have low bone density at the spine. In these patients, the postoperative increase in vertebral bone density is even more dramatic than that seen in the average patient; this has led to the recommendation that patients with low vertebral bone density also should be considered for parathyroidectomy.77

Special mention should be made of surgery in postmenopausal women with primary hyperparathyroidism.78 Many postmenopausal women with primary hyperparathyroidism have bone mass of the lumbar spine that is not below normal. Bone loss in the cancellous spine, typical of the postmenopausal state, may not be apparent. In these patients, the hyperparathyroid state could conceivably afford a relative protection, and the physician could use this information to proceed with a more conservative approach to management, especially if other guidelines for surgery are not met. On the other hand, the increase in bone density after surgery (at the spine and hip) is also seen in postmenopausal women.74

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree