Non-Hodgkin lymphomas

These are a large group of clonal lymphoid tumours, about 85% of B cell and 15% of T or NK (natural killer) cell origin (Table 20.1). Their clinical presentation and natural history are more variable than in Hodgkin lymphoma. They are characterized by an irregular pattern of spread and a significant proportion of patients develop extranodal disease. Their frequency has increased markedly over the last 50 years and with an incidence of approximately 17 in 100 000 they now represent the fifth most common malignancy in some developed countries (see Fig. 11.11). The aetiology of the majority of cases of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) is unknown although infectious agents are an important cause in particular subtypes (Table 20.2). There are also considerable geographical variation (Table 20.2). The World Health Organization (WHO) classification also recognizes age (paediatric or elderly) and site of involvement (e.g. skin, central nervous system (CNS), intestine, spleen, mediastinal) as important in disease classification.

Table 20.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of mature B-cell and T-cell neoplasms (modified), which includes the non-Hodgkin lymphomas. B-cell disorders comprise 85% of cases. T cell and NK cell together comprise 15% of cases. A few very rare subtypes have been omitted.

| Mature B-cell neoplasms | Mature T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma | T-cell prolymphocytic leukaemia |

| T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukaemia | |

| B-cell prolymphocytic leukaemia | Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukaemia |

| Splenic marginal zone lymphoma | Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type |

| Hairy cell leukaemia | Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma |

| Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma–Waldenström macroglobulinaemia | Mycosis fungoides |

| Sézary syndrome | |

| Heavy chain diseases | Peripheral T-cell lymphoma |

| Plasma cell myeloma | Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma |

| Plasmacytoma | Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALK positive |

| Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) | |

| Follicular lymphoma | |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | |

| Burkitt lymphoma |

ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, the gene on chromosome 2 which is overexpressed; NK, natural killer.

Table 20.2 Infections associated with haemopoietic malignancies.

| Infection | Tumour |

| Virus | |

| HTLV–1 | Adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma |

| Epstein–Barr virus | Burkitt and Hodgkin lymphomas; PTLD |

| HHV–8 | Primary effusion lymphoma; multicentric Castleman’s disease |

| HIV–1 | High-grade B-cell lymphoma, primary CNS lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Hepatitis C | Marginal zone lymphoma |

| Bacteria | |

| Helicobacter pylori | Gastric lymphoma (MALT) |

| Protozoa | |

| Malaria | Burkitt lymphoma |

HHV-8, human herpes virus 8; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HTLV-1, human T-lymphotropic virus type 1; MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; PTLD, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease.

Classification

The lymphomas are classified within a group of mature B-cell and T-cell neoplasms, which also includes some chronic leukaemias and myeloma which are described in Chapters 18 and 21, respectively (Table 20.1). In this chapter we consider the more common lymphoma subtypes within this classification.

Cell of origin

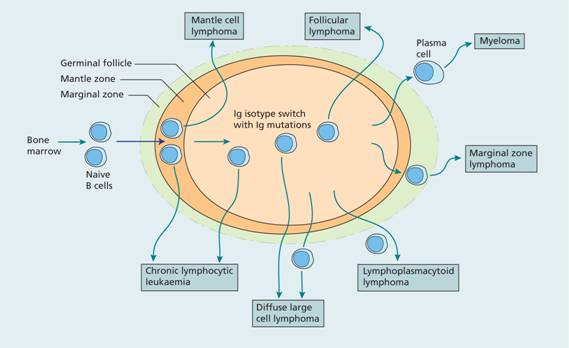

The normal B-cell development stages are illustrated in Fig. 9.10. B-cell lymphomas tend to mimic normal B cells at different stages of development (Fig. 20.2). They can be divided into those resembling precursor (bone marrow) B cells, those resembling germinal centre (GC) cells and those post-GC cells in lymph nodes. T-cell lymphomas resemble precursor T cells in bone marrow or thymus, or peripheral mature T cells.

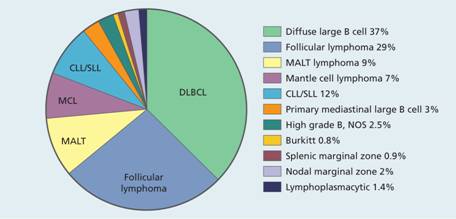

Figure 20.1 The relative frequencies of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. CLL, chronic lymphocytic lymphoma; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; NOS, not otherwise specified; PMLBCL, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma.

Figure 20.2 Proposed cellular origin of B-lymphoid malignancies. Normal B cells migrate from the bone marrow and enter secondary lymphoid tissue. When they encounter antigen a germinal centre is formed and B cells undergo somatic hypermutation of the immunoglobulin genes. Finally, B cells exit the lymph node as memory B cells or plasma cells. The cellular origin of the different lymphoid malignancies can be inferred from immunoglobulin gene rearrangement status and membrane phenotype. Mantle cell lymphoma and a proportion of B–cell chronic lymphocytic lymphoma (B-CLL) cases have unmutated immunoglobulin genes whereas marginal zone lymphoma, diffuse large cell lymphoma, follicle cell lymphoma, lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma and some B-CLL cases have mutated immunoglobulin genes.

Low-and high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphomas

The NHL are a diverse group of diseases and vary from highly proliferative and potentially rapidly fatal diseases to some of the most indolent and well-tolerated malignancies. For many years clinicians have subdivided lymphomas into low-and high-grade disease. This approach is valuable as, in general terms, the low-grade disorders are relatively indolent, respond well to chemotherapy but are very difficult to cure whereas high-grade lymphomas are aggressive and need urgent treatment but are more often curable.

Leukaemias and lymphomas

The difference between lymphomas, in which lymph nodes, spleen or other solid organs are involved, and leukaemias, with predominant bone marrow and circulating tumour cells, may be blurred. A single lymphoproliferative disease (e.g. chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and small lymphocytic lymphoma) merge with each other with the identical cell genotype and immunophenotype. Lymphoma cells may circulate (e.g. in follicular, mantle cell, diffuse large B-cell lymphomas and the Sézary syndrome). B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (B-ALL) and T-ALL and the corresponding B-and T-lymphoblastic lymphomas are different manifestations of the same diseases and are usually treated in identical fashion.

Clinical features of non-Hodgkin lymphomas

1 Superficial lymphadenopathy The majority of patients present with asymmetric painless enlargement of lymph nodes in one or more peripheral lymph node regions.

2 Constitutional symptoms Fever, night sweats and weight loss occur less frequently than in Hodgkin lymphoma and their presence is usually associated with disseminated disease.

3 Oropharyngeal involvement In 5–10% of patients there is disease of the oropharyngeal lymphoid structures (Waldeyer’s ring) which may cause complaints of a ‘sore throat’ or noisy or obstructed breathing.

4 Symptoms due to anaemia, infections due to neutropenia or purpura with thrombocytopenia may be presenting features in patients with diffuse bone marrow disease. Cytopenias may also be autoimmune in origin or due to sequestration in the spleen. Infections may occur as a result of neutropenia or reduced cell immunity (e.g. herpes zoster).

5 Abdominal disease The liver and spleen are often enlarged and involvement of retroperitoneal or mesenteric nodes is frequent. The gastrointestinal tract is the most commonly involved extranodal site after the bone marrow, and patients may present with acute abdominal symptoms.

6 Other organs Skin, brain, testis or thyroid involvement is not infrequent. The skin is also primarily involved in two unusual, closely related T-cell lymphomas, mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome.

Investigations

Histology

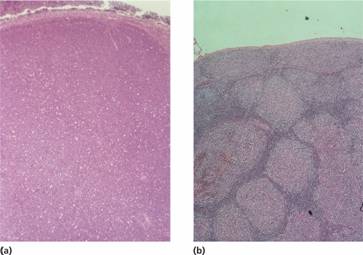

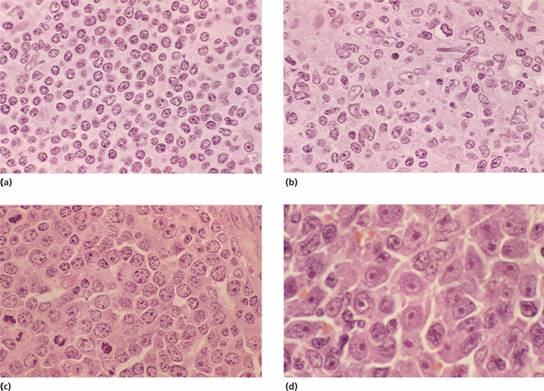

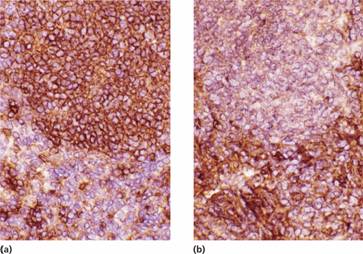

Lymph node biopsy or trucut biopsy of lymph node or of other involved tissue (e.g. bone marrow or extranodal tissue) is the definitive investigation (Figs 20.3 and 20.4). Morphological examination is assisted by immunophenotypic and, in some cases, genetic analysis (Table 20.3). For B-cell lymphomas, expression of either κ or λ light chains confirms clonality and distinguishes the disease from a reactive node (Fig. 20.5). A fine needle aspiration may be performed to exclude another cause of lymphadenopathy (e.g. tuberculosis, carcinoma) but is not useful in establishing a diagnosis of lymphoma.

Figure 20.3 Non–Hodgkin lymphoma: histological sections of lymph nodes showing: (a) a diffuse pattern of involvement in lymphocytic lymphoma with the normal architecture totally replaced by neoplastic lymphocytic cells; (b) a follicular or nodular pattern in follicular lymphoma–the ‘follicles’ or ‘nodules’ of neoplastic cells compress surrounding tissue and lack a mantle of small lymphocytes.

Figure 20.4 Non–Hodgkin lymphoma: high power view of lymph node biopsies: (a) Lymphocytic lymphoma showing predominantly small lymphocytes with round nuclei containing densely clumped heterochromatin. (b) Mantle cell lymphoma: showing characteristic deformed pattern of small lymphocytes with angular nuclei (‘centrocytes’). (c) Diffuse large B–cell lymphoma: the neoplastic cells are much larger than normal lymphocytes and have a round nucleus with prominent nucleoli, many of which are adjacent to the nuclear membrane (‘centroblasts’). A number of mitotic figures are seen. (d) Diffuse large B–cell lymphoma showing large neoplastic cells with a single prominent nucleolus and abundant dark–staining cytoplasm (previously termed immunoblasts).

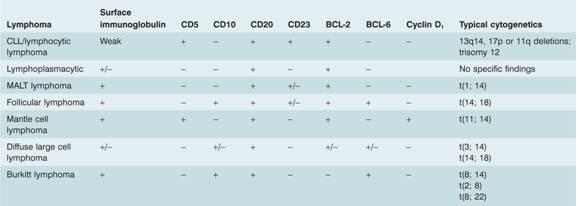

Table 20.3 Characteristic immunophenotype and cytogenetics of B-cell lymphomas.

CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; MALT, mucosa – associated lymphoid tissue.

More detailed cytogenetics are given in Table 11.1 .

Figure 20.5 Non–Hodgkin lymphoma: lymph node stained by immunoperoxidase shows (a) brown ring staining for κ in the malignant lymphoid nodule, and (b) no labelling for λ confirming the monoclonal origin of the lymphoma.

Laboratory investigations

1 In advanced disease with marrow involvement there may be anaemia, neutropenia or thrombocytopenia (especially if the spleen is enlarged or there are leucoerythroblastic features).

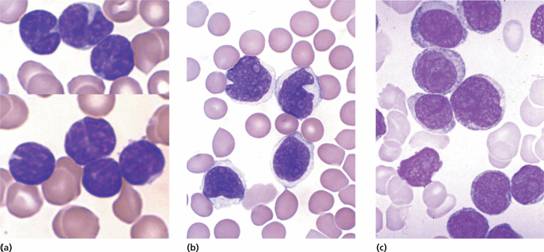

2 Lymphoma cells (e.g. mantle zone cells, ‘cleaved follicular lymphoma’ or ‘blast’ cells) may be found in the peripheral blood in some patients (Fig. 20.6). 3 HIV should be tested for in all patients.

Figure 20.6 Blood involvement by malignant lymphoma: (a) small cleaved lymphoid cells in follicle centre cell lymphoma; (b) mantle cell lymphoma; (c) large B–cell lymphoma.

4 Trephine biopsy of marrow is valuable (Fig. 20.7). Paradoxically, bone marrow involvement is found more frequently in low-grade malignant lymphomas.