Germany

Long-term care insurance and medical care of dementia patients

At present more than 1 million people in Germany have moderate to severe dementia. Most live in private households, while about 40% are institutionalised. Statutory health insurance covers the cost of medical services. To alleviate the enormous costs involved in long-term care for elderly patients with chronic disorders such as dementia, the long-term care insurance law was established in 1994. While health insurance is a fully comprehensive system, long-term care insurance only provides limited cover. All members of the health insurance system are automatically covered by long-term care insurance. Employees who are not covered by the social insurance system (i.e. civil-servants, the self-employed, etc.) are usually members of a private insurance scheme. Long-term care insurance follows three principles:

Evaluation of after care needs leads to a person being assigned to one of three care levels: considerable (I), intensive (II) or highly intensive (III) care. The long-term care insurance law went through several revisions and in 2008 a major reform was introduced. It included an increase in benefit payments and provision of more thorough care for severely impaired persons, including those with dementia. At present, the total number of beneficiaries is about 2.36 million, 69.2% of whom receive home care and 30.8% institutional care, almost exclusively in nursing homes [2].

Almost all patients with dementia first contact a primary care physician, many of whom are not well enough trained to deal with psychogeriatric disorders. They rarely refer patients with dementia to psychiatrists or neurologists. Only 15% of dementia patients receive anti-dementia drugs [3].

Outpatient services

Community nursing services were established in Germany in the early 1970s. They provide primarily medical care (dressing of wounds, administration of injections, etc.) and basic nursing care (personal hygiene, etc.). Staff – mainly nurses – frequently encounter elderly patients with psychiatric disorders, and many of those have dementia. Based on a national survey, 25.8% of dementia patients living at home use such outpatient services. A further 20% use other professional services providing delivered meals and performing basic housework. Apart from very few exceptions, dementia patients using professional outpatient services were mainly cared for by an informal caregiver. More than half of the dementia patients were only cared for by informal caregivers [3].

Specialised outpatient services have been established at many state and university psychiatric hospitals, focusing on early recognition of cognitive disorders, pharmacological treatment, provision of cognitive training programs, training of primary care physicians and psychiatrists, as well as counselling for care-providing relatives.

Geriatric day care

Institutions offering geriatric day care are an important constituent in the system of care provision. In general, trained nurses at these units offer everyday-life activities, games, individual training and outings, aiming to enhance patients’ well-being and skills and to reduce caregiver burden. A study carried out in 17 geriatric day-care facilities revealed that 58.6% of clients suffered from moderate to severe dementia. In addition, symptoms of depression and behaviour problems were observed among a substantial number of attendees [4]. A longitudinal study reported significant positive effects of day care on well-being and dementia symptoms [1]. However, compared to outpatient services and nursing homes, geriatric day-care units play only a minor role. A national study revealed that only about 2% of dementia patients living in private households use geriatric day care [3].

Nursing home care

Care provided by old-age homes has changed greatly over the last 30 years: the original focus on residential care has since given way to a focus on nursing care. Most recent statistics indicate that this trend persists: the number of nursing homes increased from 9165 (2001) to 9700 (2009). Parallel to this development, the number of nursing home residents rose from 604,000 (2001) to 711,000 (2009) [2]. Nursing homes are key providers of dementia care: a national study revealed that 68.6% of all nursing home residents have moderate to severe dementia [5]. More than half of all nursing homes in Germany provide traditional care (dementia patients and non-dementia patients live in the same residential unit). Special dementia care in nursing homes can be realised on the basis of either a segregated or a partially segregated model:

- the segregated model involves specialised, segregated round-the-clock care for dementia patients living in a special care unit

- the partially segregated arrangement means patients with dementia share a residential unit with non-demented residents but spend part of the day in a special group for dementia patients.

Political efforts have been made to improve the institutional care of dementia patients. At present, 28% offer segregated care, and 15% partially segregated dementia care [5]. The forerunner of special dementia care was the city of Hamburg. To fulfil the special needs of dementia patients with behaviour problems, a segregative and a partially segregative programme was established for 750 residents. Each is characterised by much higher staffing ratios, specialised staff training, regular psychogeriatric care and enhanced milieu-therapeutic concepts, including architectural changes. The extra costs that such specialised dementia care entails are, in general, passed on to the resident [6].

Comparison of segregated and partially segregated dementia management in Hamburg

The activity rates of dementia patients, the number of visits from relatives and their involvement in nursing and social care were much higher in the partially segregative care arrangement as opposed to segregative care. Among the residents in segregative care, however, significantly more biographical information was collected and the proportion of patients receiving psychogeriatric care was also higher. Dementia patients in these homes received more psychotropic medication with significantly more prescription of anti-dementia drugs and antidepressants and less frequent prescription of antipsychotic drugs.

Comparison of special dementia care in Hamburg to traditional dementia care in Mannheim

Compared to traditional integrative care, the special dementia programme in the city of Hamburg revealed a better quality of life and quality of care: a higher level of volunteer caregiver involvement, more social contact with staff, fewer physical restraints and more involvement in home activities. In both settings, about three-fourths of the dementia patients received psychotropic drugs. However, residents in special dementia care were treated significantly less often with antipsychotics and more often with antidepressants [6].

Summary and conclusions

The number of dementia patients is expected to double within the next 40 years: in 2050 between 2.2 and 2.7 million cases are expected [7]. At the same time, the number of family caregivers will decrease, giving rise to an enormous demand for professional dementia care, particularly nursing homes. Significant differences in some indicators of quality of life point in favour of the model pioneered in Hamburg. However, there are still quality indicators (e.g. activities offered within nursing homes, appropriate medication and use of anti-dementia drugs) where special care was not significantly better than traditional care. Since these areas can be modified by intervention, improvements to the special care programme should be made. It could be shown that only about 10% of the dementia patients in traditional nursing homes fulfil the criteria for special dementia care as applied in the Hamburg approach. It is also important to provide adequate care for the vast majority of patients in traditional nursing homes who do not benefit from special care programmes because they are immobile or do not exhibit severe behavioural problems [6].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the INTERREG IVB project ‘Health and Demographic Changes’.

References

1. Zank S, Schacke C (2002) Evaluation of geriatric day care units: effects on patients and caregivers. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences 57B(4):348–357.

2. Statistisches Bundesamt (2011) Pflegestatistik 2009. Pflege im Rahmen der Pflegeversicherung. Deutschlandergebnisse. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt.

3. Schäufele M, Köhler L, Teufel S, Weyerer S (2006) Betreuung von demenziell erkrankten Menschen in Privathaushalten: Potenziale und Grenzen. In: Schneekloth U, Wahl H-W (eds), Selbständigkeit und Hilfebedarf bei älteren Menschen in Privathaushalten. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, pp. 103–145.

4. Weyerer S, Schäufele M, Schrag A, Zimber A (2004) Demenzielle Störungen, Verhaltensauffälligkeiten und Versorgung von Klienten in Einrichtungen der Altentagespflege im Vergleich mit Heimbewohnern: Eine Querschnittsstudie in acht badischen Städten. Psychiatrische Praxis 31:339–345.

5. Schäufele M, Köhler L, Lode S, Weyerer S (2009) Menschen mit Demenz in stationären Pflegeeinrichtungen: aktuelle Lebens- und Versorgungssituation. In: Schneekloth U, Wahl H-W (eds), Pflegebedarf und Versorgungssituation bei älteren Menschen in Heimen. Demenz, Angehörige und Freiwillige, Beispiele für Good Practice. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, pp. 159–221.

6. Weyerer S, Schäufele M, Hendlmeier I (2010) Evaluation of special and traditional dementia care in nursing homes: results from a cross-sectional study in Germany. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 25:1159–1167.

7. Doblhammer G, Ziegler U (2011) Perspective for dementia trends: predictions derived from demographic research. In: Dibelius O, Maier W (eds), Versorgungsforschung für dementiell erkrankte Menschen. Health services research for people with dementia. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, pp. 11–18.

Spain

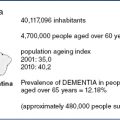

Demographic and epidemiological aspects

Just over 17% of the Spanish population is over 65, approaching 25% in several regions. Those over 80 comprise 5.3% with a third living in rural areas. Prevalence ranges between 5% and 10% [1], which means that 3.5 million people are affected. The resulting expenditure is estimated to be approximately €30,000 per year per patient.

The Spanish national health service (SNS)

Spain has a complex political structure consisting of 17 Autonomous Regions. The SNS guarantees free and universal health care, and patients are only required to pay part of the cost of prescribed medications [2].

Recently, an act was passed recognising the universal right to social benefits for all senior citizens and persons with disabilities who need assistance for their basic daily activities, thus providing a legal foundation for long-term care [3]. However, the Autonomous Regions are responsible for the organisation and funding of social and health care, resulting in significant differences in the care provided to people with dementia, leading to sharp criticism. Over the last two decades there has been a remarkable growth in social awareness of the challenges posed by dementia. This has led to the development of a variety of educational programs (ranging from university degrees to the training of informal carers), handbooks and monographs describing the basic principles of dementia care and a number of consensus documents [4]. Recently, the Spanish Ministry of Health included these in its Clinical Guidelines [5].

Health and social care models

In the 1990s, Catalonia pioneered the development of a bio-psycho-social model of dementia care, called ‘Socio-Sanitario’. In 2000, a report published by the Ombudsman analysed the challenges faced by older people, specifically addressing the needs of and care resources required by people with dementia and calling for the government to take a number of specific measures.

The Catalan model inspired other regions, but in most cases, nothing came to fruition because of funding problems: it established a network for the diagnosis and treatment of dementias, but it has not been replicated elsewhere.

Catalonia implemented a Socio-Health Master Plan, co-financed by the Department of Health and the Department of Welfare and Family, which is being further developed under the Program for the Prevention and Care of Chronicity (PPAC) [6]. This model consists of outpatient and inpatient services, the inpatient services being of two types: psychogeriatric long-stay and medium-stay units. The latter are for patients with dementia and behavioural problems who cannot be managed at home or in nursing homes. Outpatient services include psychogeriatric day hospitals for mild to moderate cases, home-care teams (PADES) and Outpatient Teams for Cognitive Disorder Assessment (EAIA-TC), consisting of neurologists, geriatricians, psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, social workers and, in some cases, nurses. There are 30 such teams across Catalonia [7].

Galicia has also pioneered a model of psychogeriatric care and formulated a Dementia Plan [8]: it has put in place an important public network of Day Centres catering mainly for people with dementia [9].

A recent study by the Spanish Society of Psychogeriatrics (SEPG) shows that the situation in most other regions is more precarious. With family carers as the main source of support for patients with dementia, the Spanish Confederation of Relatives of Alzheimer Patients (CEAFA) not only asks for more action, but also provides guidance and care. Funded by the respective regional governments, it runs day centres or ‘Relief Units’, but this is not coordinated with the wider care sector.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree