Argentina

In the last decades, the Argentinian population has aged faster than anticipated, resulting in an exponential growth of age-dependent illnesses such as dementia. The increase in dementia in the next 20 years will be much faster in low- to medium-income countries than in richer nations.

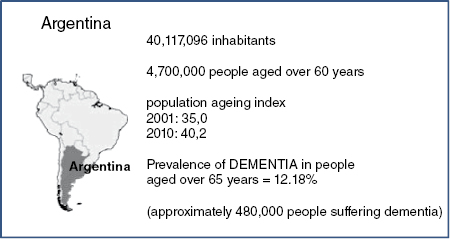

In 2010, Argentina recorded just over 40 million inhabitants, with 4.7 million being over 60, proving that our country is not free from the problem [1]. The population pyramid is likely to change into a somewhat inverted pyramid, similar to that of developed countries, due to this increase. In this context the prevalence of dementia is estimated as 12.18% of people over 65 [2]. An epidemiological study in Cañuelas (a city in Buenos Aires province) found that 23% of those over 60 had cognitive impairment [3]. According to these numbers, we can infer that there are approximately 1 million people with cognitive impairment and 480,000 with dementia in the country [4] (see Figure 11.1).

However, there is a lack of epidemiological data needed properly to plan health strategies in dementia care. A recent initiative of the National Health Department to address this is the Registry of Cognitive Pathologies in Argentina (ReDeCAr, Registro de Deterioro Cognitivo en Argentina), which – so it is hoped – will in the short term lead to a national plan to tackle dementia [5]. ReDeCAr is a prospective case register in hospitals and health centres throughout the country, using standardised software, enabling epidemiological observations, centrally recorded by the National Health Department.

This allows us over time to build a centralised database of patients, which will produce a national and regional epidemiological picture, in turn enabling us to generate progressive policies in cognitive impairment and dementia, adapted to real needs [6].

Dementia creates an important economic, social and personal burden. Local studies were therefore conducted to establish the costs of dementia. A study carried out by Allegri et al. showed that the annual costs were US$3420.40 in mild Alzheimer’s dementia and up to US$9657.60 in severe forms, increasing to US$14.447.68 if it included care paid for by the patient’s family [7]. Another recent study showed that different types of dementia (Alzheimer’s, vascular and frontotemporal dementia) have different costs. Vascular dementia is slightly more expensive, probably because of the presence of behavioural symptoms and impairment in functioning [8].

Dementia care in Argentina is shared between the public and private sectors. The public sector provides care to low- and middle-income populations, mainly in hospitals, whereas the private sector tends to provide care to middle- and high-income populations, including home assistance [9]. Unfortunately, this distribution is not equitable: more than 17 million people (43% of the population) have access which is limited to the Public Health System: this segment of healthcare receives only 28% of total health resources [10]. On the other hand, most elderly people (91% of people over 65) receive medical care from Social Security Support in a model which combines health with social care needs, but the economic instability over the years leads to variable efficacy in addressing the demands posed by the illness. Despite this, in the last 5 years, the system has shown a slight improvement [11].

With regard to assessment, diagnosis and treatment of dementia, Argentina has an unequal distribution of specialists (neurologists, psychiatrists and geriatricians): most are located in large cities, while there is a shortage in small towns and rural areas. The facilities needed for accurate diagnosis are scarce, except in Buenos Aires and a few other large provincial cities. There are few specialists trained in geriatric neuropsychiatry, and more education for lay people is needed as well [12].

In the last 10 years, the role of memory or dementia clinics has become more important. Most of these memory clinics are based on private initiatives. Recently, the directors of the 20 most important memory clinics were interviewed [13]. Among its main findings this survey showed that 70% of these memory clinics only cater to private patients. Sixty percent are run by neurologists. However, every clinic had at least one psychiatrist on their staff. Only 35% of the centres perform clinical trials, and only 20% of the groups present original papers or studies at meetings. Sixty percent of the centres have day-care services, 35% of the clinics provide training, and 80% offer counselling for spouses and caregivers [13].

Previous reviews have identified that in most countries, more than two-thirds of people with dementia live at home, and the majority is cared for by family members [14]. Argentina has a similar profile: most senior citizens live at home with their families, but approximately 15% live in nursing homes [15–17]. Family and non-family caregivers need information and counselling about dementia care. In our country, these resources are improving: ALMA (‘Asociación de Lucha contra el Mal de Alzheimer’ – Association against Alzheimer’s Disease, a member organisation of Alzheimer’s Disease International) is the main organisation fighting the disease: it works locally, to promote and offer care and support for people with dementia and their carers. It has more than 20 associations around the country [18]. Our group wrote the first book in the country about dementia family care in 2003, re-edited in 2010 [19]. More books and publications are being published, aimed to help families with early detection and treatment of dementia [20,21].

Early diagnosis of dementia is another challenge. It may be possible to increase the predictive validity of prodromal risk indicators based upon cognitive decline and subjective impairment. One widely advocated approach is the incorporation of disease biomarkers that may indirectly represent the extent of underlying neuropathology: structural neuro-imaging (medial temporal lobe or hippocampal volume), functional neuroimaging (Aβ ligands to visualise amyloid plaques in vivo) and cerebrospinal fluid [22]). In February 2011, FLENI (‘Fundación para la Lucha contra las Enfermedades Neurológicas de la Infancia’ – based in Buenos Aires [23]) joined ADNI (‘Alzheimer Disease Neuro Imaging’, a public sector-industry partnership founded in 2004 [24]) to develop biomarkers to predict the progression from normal ageing or mild cognitive impairment to the dementia phase of Alzheimer disease. This research involves volumetric magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography with fluorine-18-labeled deoxyglucose and Aβ ligands (PiB and AV45), cognitive and neurological evaluations, and analyses of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers (Aβ42, tau and f-tau) [24,25]. In addition, FLENI houses the only brain bank in South America [23]. Another institution in Argentina (‘CEMIC’) studies the diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s with PET and Aβ ligands [26].

In summary, despite having weaknesses, Argentina is currently fighting strongly to improve the quality of life of people with cognitive impairment and dementia and their carers around the country (see Table 11.1). If our governments act urgently to develop research and care strategies, the impact of this disease can be reduced.

Table 11.1 Argentina: state of affairs regarding dementia

| Weaknesses | Current reality | Future challenges |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Conflict of interest: none.

References

1. INDEC (2010) Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos. Censo Nacional de Población y Viviendas 2001 y 2010. Available at: http://www.indec.gov.ar (last accessed on 20 February 2013).

2. Pages Larraya F, Grasso L, Mari G (2004) Prevalencia de las demencias de tipo Alzheimer, demencias vasculares y otras demencias en la República Argentina. Revista Neurológica Argentina 29:148–153.

3. Arizaga RL, Gogorza RE, Allegri RF, Barman D, Morales MC, Harris P, et al. (2005) Deterioro cognitivo en mayores de 60 años en Cañuelas (Argentina). Resultados del Piloto del Estudio Ceibo (Estudio Epidemiológico Poblacional de Demencia. Revista Neurológica Argentina 30(2):83–90.

4. Allegri RF (2011) Primer Registro Centralizado de Patologías Cognitivas en Argentina (ReDeCAr). Resultados del Estudio Piloto. Publicación del Ministerio de Salud 5:7–9.

5. Melcon CM, Bartoloni L, Katz M, Del Mónaco R, Mangone C, Melcon MO, et al. (2010) Propuesta de un Registro centralizado de casos con Deterioro Cognitivo en Argentina (ReDeCAr) basado en el Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica. Neurología Argentina 2(3):161–166.

6. Katz M, Bartoloni LC, Melcon CM, Del Mónaco R, Mangone CA, Allegri RF, et al. (2011) Presentación del Primer Registro Centralizado de Patologías Cognitivas en Argentina (ReDeCAr). In: Sistema de Vigilancia Epidemiológica en Salud Mental y Adicciones, Boletín 5. Ministerio de Salud. 11–14.

7. Allegri RF, Butman J, Arizaga RL, Machnick G, Serrano C, Taragano FE, et al. (2006) Economic impact of dementia in developing countries: an evaluation of costs of Alzheimer-type dementia in Argentina. International Psychogeriatrics 18:1–14.

8. Galeno R, Bartoloni L, Dillon C, Serrano C, Iturry M, Allegri RF (2011) Clinical and economic characteristics associated with direct costs of Alzheimer’s, frontotemporal and vascular dementia in Argentina. International Psychogeriatrics 23(4):554–561.

9. Ritchie CW, Ames D, Burke J, Bustin J, Connely P, Laczo J, et al. (2011) An international perspective on advanced neuroimaging: cometh the hour or ivory tower? International Psychogeriatrics. 23(Suppl):558–564.

10. World Health Organization (2008) Countries: Argentina. Available at: http://www.who.int/countries/arg/en (last accessed on 21 February 2013).

11. PAMI (2011) National Institute of Social Services for Retired People and Pensioners (INSSJP/PAMI). Available at: http://www.pami.org.ar (last accessed on 20 February 2013).

12. Sarasola D, Taragano F, Allegri R, Arizaga R, Bagnati P, Serrano C, et al. (2006) Geriatric Neuropsychiatry in Argentina. IPA Bulletin p 10 and 19.

13. Kremer J (2011) Memory Clinics in Argentina. Questionnaire. Available at: http://www.institutokremer.com.ar (last accessed on 20 February 2013). Data on file.

14. Rabins P, Lyketsos CG, Steele CD (1999) Practical Dementia Care. 7, p. 111.

15. Taragano TE (2011) Síntomas neuropsiquiátricos en la Enfermedad de Alzheimer. Revista de ALMA (Asoc. Lucha Mal de Alzheimer). pp. 10–11.

16. Pollero A, Gimenez M, Allegri RF, Taragano FE (2004) Síntomas Neuropsiquiátricos en pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer. Vertex 15(55):5–9.

17. Taragano F, Mangone C, Comesaña Diaz E (1995) Prevalence of neuropsychiatric disorders in nursing homes. Revista de la Asociación Argentina de Establecimientos Geriátricos.

18. ALMA – Asociación de Lucha contra el Mal de Alzheimer (2011) Misión de ALMA. Revista de ALMA. p. 7. Available at: http://www.alma-alzheimer.org.ar (last accessed on 20 February 2013).

19. Bagnati PM, Allegri RF, Kremer JL, Taragano FE (2010) Enfermedad de Alzheimer y otras demencias. Manual para la familia. Editorial Polemos, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

20. Manes F (2005) Convivir con personas con EA u otras demencias. D. Palais Ediciones, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

21. Gonzalez Salvia M (2006) Manual para familiares y cuidadores de personas con Enfermedad de Alzheimer. Editorial del Hospital Italiano, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

22. Alzheimer Disease International (ADI) (2011) World Alzheimer Report. p. 12.

23. Memory and Aging Center, Institute of Neurology, FLENI, Buenos Aires, Argentina Available at: http://www.fleni.org.ar (last accessed on 21 February 2013).

24. ADNI (Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative) (2011) FLENI partnership. Available at: http://www.alz.org/research/funding/partnerships (last accessed on 20 February 2013).

25. Burton A (2011) Big science for a big problem: ADNI enters its second phase. Lancet 10:206–207.

26. Neurosciences Department, CEMIC (Centro de Estudios Médicos e Investigaciones Clínicas) Available at: http://www.cemic.edu.ar (last accessed on 20 February 2013).

Brazil

Ageing in Brazil

Traditionally considered a ‘young’ country, Brazil has in recent decades seen its population age significantly. This is set to continue: whereas the elderly population will increase by 2–4% per year, the young population will decline. According to United Nations projections, the elderly population in Brazil will increase from 3.1% of the total population in 1970 to 19% in 2050. In particular, the ‘oldest old’ will more than triple between 1990 and 2020, from 1.9 to 7.1 million [1].

Brazil has a heterogeneous ethnic and racial origin population with different socio-economic and cultural profiles. The majority of the population (84%) lives in urban areas. Thirteen cities have more than 1 million inhabitants, including Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, which are among the 30 largest cities in the world.

According to the General Household Survey of 2009, the population over 60 is estimated at 21 million, the majority of whom are female (55.8%). The education level among the elderly is very low: 50.2% with less than 4 years of schooling. Less than 12% live in households with up to half minimum wage per capita, 77.4% receive retirement benefits and/or survival pensions from Social Security, and 37.5% of males and 14.4% of females still work after age 60 [2]. At the same time, traditional versions of family support are declining.

The ageing process has led to an increase in chronic and degenerative diseases and disabilities. Two patterns of morbidity currently coexist: one typical of poor living conditions (infectious and parasitic communicable diseases) and the other of more developed societies (chronic and degenerative non communicable diseases). The resulting ‘epidemiologic polarisation’ increases significant health gaps between different social groups and geographical areas within the country [3].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree