It was noted above that the business case process is usually iterative and therefore the associated documentation is ‘live’: there must be a stipulated structure which facilitates formal change control and acceptance, meaning that the ‘owners’ of the project should be able to amend and change the document whenever necessary, but there should be a process whereby such changes are endorsed and accepted by a supervising managerial level above the level of project management. This ensures proper governance of the process and clear accountability when things get difficult or certain aims or milestones are not being met.

In the Background section an overview of why the project is required should be presented, along with the expected benefits and how it is aligned with the agreed business or service strategy of the organisation and therefore its priorities or simply how it is aligned with national strategies and frameworks with respect of health service development and delivery.

In the Project Scope section, which can be thought of as a self-contained summary of the proposed project with an explicit description of its size and complexity, different options should be covered and a clear justification stated for the recommended solution. Assumptions as well as any constraints and dependencies should be highlighted. For the ‘recommended solution’ the delivered outcomes should be specified explicitly, along with their associated planned benefits.

In the Benefits and Costs section it should be presented clearly how much money, people and time will be needed to deliver the proposed project and where and when the benefits will be realised. Inevitably, assumptions will have to be made, and these should be stated explicitly. For any project the benefits and costs have both financial and non-financial dimensions. Business cases in health care crucially include financial calculations, but the investment decision is not only about money. The nature of public sector organisations in general, and in our case, health services in particular (whether in the public sector or not), necessitate that other factors, such as social inclusion, quality of life, independence and public and societal values, will be examined to assess the most appropriate use of scarce resources. The traditional ‘cost-benefit analysis’ is a comparative evaluation tool that can include the relative assessment of different potential projects. Non-quantifiable characteristics of a proposed project should also be included. It is an appraisal method attempting to put monetary values on all benefits arising from a project, which are then compared with the project’s total cost. The technique is widely used, especially for large-scale infrastructure projects in the public sector, but there are problems, particularly with putting quantitative values on essentially qualitative outcomes: these difficulties are discussed in detail in Chapter 10.

The objective of the Project Management section of the business case document is to demonstrate that it is achievable with the proposed resources. What are the required resources and how will the project team be managed? If there are any non-project dependencies, such as IT implementations, then these must be highlighted and discussed and interdependencies with wider service environments, such as social services or insurance frameworks, which may impact on the proposal, should be clarified or at least identified. There has to be a detailed project plan and work schedules, with workload estimates and critical paths broken down into manageable steps. Project controls and reporting must be clear.

In the Critical Success Factors section a discussion of the factors critical for a successful outcome should be presented. These ought to include any risks that can be identified as potentially jeopardising a successful completion of the project, and in listing these risks, it is essential to indicate how each one will be managed and what possible ways there are to mitigate against them.

In the Approvals section the formal sign-offs for different aspects of the project, including dependencies, should be presented formally: this ensures that at any stage it is clear who is responsible and accountable for ascertaining that a particular milestone has or has not been achieved.

Thus, as a document, the business case should demonstrate that all issues have been considered thoroughly and in a balanced manner. There will sometimes be an accompanying short formal presentation, which should leave sufficient time for questions and answers. Cases do not succeed on presentation skills per se, but a good presentation can help to focus minds and steer the decision-makers’ thinking in the right direction. If a presentation is planned, one should try and anticipate any reasonable critique or likely questions and prepare answers and rebuttals as much as possible.

We present two case studies to illustrate the above characteristics in more practical detail.

Adam, a qualified dementia nurse, was a newly promoted manager of a Dementia Care Unit. This unit was specially built in 2001 for people with severe dementia, accommodating 36 patients at any one time. It had not had any improvements or significant repair work carried out since it was opened.

One Monday morning Adam was informed of a serious incident that had taken place over the weekend: a patient had fractured her hip when a chair had collapsed under her and she was now in the general hospital. His first meeting that morning was with the hospital safety inspector who would advise on the action he needed to take.

The safety inspector told him that all furniture had to be checked, and it was possible that much would have to be replaced as a matter of urgency. To avoid the risk of a repeat of the weekend’s incident, Adam was tasked with ensuring this work would be carried out as a priority with a deadline of 2 weeks.

He first called the Works Department to ask for someone to check all the furniture and the outcome of this ‘risk assessment’ was that by and large all furniture in the day area had to be replaced. The Works Department informed him he needed to have authorisation from the Finance Department before they could go ahead with ordering replacements so he rang them and explained what was needed. He was advised that the work likely involved an amount of money over the spending threshold of £2000, which meant they needed him to submit a Business Case. He was provided with a form and was told to submit the completed form to his manager for budgetary approval, before returning the form to Finance.

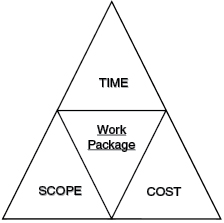

The form was daunting: Adam was a nurse and some of the terms used on the form, such as ‘financials’ and ‘benefits realisation’ were completely new to him. He decided to go onto the ward to have another look and to collect his thoughts and realised that the unit itself was looking generally ‘tired’ (to put it politely): not only was the furniture worn out, the place itself had not been touched in 11 years. Curtains were looking faded and walls could do with freshening up. He made some notes, decided that he might as well try and draft a business case for a more comprehensive revamp of the unit and attacked the form with renewed enthusiasm. Needing some assistance with this, he arranged to meet up with someone from ‘Finance’, and during this meeting he explained why there suddenly appeared to be more to the business case than just replacement of potentially dangerous furniture. ‘Finance’ explained to him that any project is driven by three key elements and these needed to be ‘in balance’ if the project was to succeed:

Adam’s enthusiasm for re-decorating the unit along with replacing all the furniture was changing the SCOPE of the original work package. This would have a direct effect on the other two: TIME and COST. He was conscious of the fact that he faced a non-negotiable deadline of 2 weeks, and he realised that it was of course unlikely he could achieve the aim of a full revamp within that timeline. A bit disheartened he decided to focus on replacing the dangerous furniture, limiting his business case to the original scope of the work package. After obtaining some costings he completed the business case: ‘scope’, ‘cost’ and ‘time’ were in balance. He submitted the form for budgetary approval, and the furniture was replaced within the time limit.

However, he was still disappointed about the missed opportunity of having the unit refurbished. He realised the importance of achieving the TIME element of his original work package in order to comply with the safety inspector’s requirement and as such he fully understood he had had to reduce the SCOPE of the work, but he still had a vision for the newly decorated unit.

He decided to submit a second business case, this time for the full refurbishment, so in effect he was phasing the work in a way he had not foreseen. Given that the earlier pressure of the TIME element was now not an issue, he expanded the SCOPE according to his earlier plan, again obtained quotes for the COST and then re-estimated the TIME it would take to complete the work. He now felt reasonably at ease with drafting a business plan, more so than he would have expected prior to the unfortunate incident. At this point the success of ‘phase 2’ was likely to be dictated by the COST element, but here is where this story ends …

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree