CHAPTER 44 Women’s Reproductive Health

Introduction

There are currently fifteen million refugees and asylum seekers worldwide,1 a percentage of whom will resettle in host countries. The health of resettling refugees is not well known since health data are rarely reported for refugees separate from all immigrants combined. Refugees, individuals forced from their homeland and unable to return for a period of time due to sociopolitical instability (paraphrased from UNHCR1), and asylum seekers arriving in resettlement countries, are thought to be at greater risk than the general population for several harmful health outcomes as a result of their migration history. Anecdotal reports from professionals suggest that childbearing and other aspects of reproductive health add an additional burden on female refugees, which places them in a particularly disadvantaged position. These suppositions have not been systematically examined.

Reports would suggest that screening and care provided to resettling refugees is anything but systematic.2–5 Policy makers and program planners, however, generally see knowledge of health ‘events’ (including illness episodes and health/social services use) as required for optimal health planning.6 The extent and nature of health ‘events’ and their determinants in resettling refugee women and their infants becomes even more relevant when the role of development from birth to 6 months of life on future health outcomes is considered.7

Review of the Literature

Refugee women’s reproductive health prior to resettlement

There are differing opinions of the effects of migration on fertility and family planning.8 One suggests that forced migration increases fertility as refugees satisfy their desire to repopulate, in order to replace deceased children or soldiers and as migration produces a healthier, more stable environment (for example, in some camp situations) with improved healthcare services and nutrition. The opposing opinion suggests that migration decreases the fertility rate of refugees because of perceived uncertainty of the future, economic instability, and marital separation. Fertility rates have also been found to vary with knowledge and availability of contraception. In sum, there are no known common fertility patterns of refugees.

Refugee women appear to be at greater risk than other women for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), for a variety of reasons.8 Migration often occurs without the accompaniment of spouses, thereby increasing the likelihood of sexual activity outside stable relationships. Military operations have been found to be associated with an increase in STI transmission and many refugees are fleeing war-torn areas or must travel through or encamp in those areas. Economic disruption may require refugee women to be involved in sexual activity to acquire food or other goods for themselves or their children. Psychological stresses, including the need for protection from soldiers or men living in or near the camps, may also lead to the granting of sexual favors. Men entrusted to ensure the travel of refugee women through to a safe haven may demand sexual favors. Migration appears to increase the incidence of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV; e.g. rape, forced impregnation, and other forms of violence), which in turn promotes the spread of STIs.

The use of SGBV by one group to oppress another has long been in existence in times of war. Incidence is difficult to estimate since it is grossly under-reported. The use of SGBV as a weapon of war has come to light more recently, due to the atrocities in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia.9,10 Systematic rape may be used as a weapon for ethnic cleansing. Women younger than 25 years of age, and of a particular ethnic background, are thought to be at greater risk for SGBV, as are women of low socioeconomic status who live in circumstances with poor security. SGBV leads to the spread of HIV and STIs; can lead to genital, anal, and other physical injuries and to unwanted pregnancies; and accounts for a variety of psychosocial difficulties for women.9

Domestic violence plagues many women worldwide and this form of violence may begin or escalate during pregnancy, or patterns of abuse may be altered with more injuries to the abdominal area attempted.11 Physical and psychological torture has been extensively reported to occur to both women and men and takes many forms.12 All organ systems may be affected and in particular the musculoskeletal and nervous systems. Post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, somatization, and other psychological effects are common sequelae. Refugee men may be subject to general physical torture while refugee women are subject to sexual abuse.

Female circumcision affects one hundred million girls and women worldwide and is considered by many to be a form of SGBV. It is performed in 26 African countries and by groups in Oman, South Yemen, the United Arab Emirates, Indonesia, and Malaysia.13,14 In addition to the chronic health effects of these procedures, including urinary tract infections, painful menstruation, and scarring, difficulties can arise in passing the infant through the birth canal and there is increased risk of uterine rupture.15

It is generally assumed that refugee women have poorer pregnancy outcomes than other women, although few data are available to refute or support this claim. It is likely that infant and pregnancy health outcomes such as mortality are poorer in war-affected populations, although perhaps no worse than in refugees’ own country of origin once restabilization of the country or population occurs.8 This may be explained by the relatively greater availability of healthcare services in refugee camps. There is also a dearth of data on other maternal health outcomes such as morbidity and nutritional status. Safe motherhood is thought to be determined by factors shared by settled populations: socioeconomic status, age, education, access to services, and urban versus rural habitation.8 However, what distinguishes migrating refugee women from settled women is their increased exposure to war, SGBV, abuse and torture, and STIs/HIV.

Several reports have considered the needs of refugee women16 and the reproductive healthcare services that they are receiving.17,18 A great deal of effort is now being placed on ensuring that a minimum set of reproductive health services is made available to refugee women in camps.

Migration and health in resettlement countries

Immigration classifications vary by country, although the concept of the ability to freely return to the country of origin usually distinguishes immigrants, who have that option, from refugees, who do not. The differences in experiences between those in these two broad categories have been reviewed.19 When examined together, immigrants are multiethnic, their mother tongue and the language used vary, and they have a variety of religious traditions, lifestyles, and political alliances. As opposed to refugees, other immigrants choose to resettle. They are motivated to leave their countries and re-establish themselves in a new country in the hope of a better life. Their departures are planned and they are able to return to their countries of origin if they choose. On the other hand, refugees are forced to leave their countries to ensure their survival. Their arrival in the new country is in many respects involuntary and they are not able to return to their countries of origin. Their departures from their homelands are often from violent situations in which they have not been able to put closure to important relationships and they may feel guilty for leaving their families or friends. All immigrants will go through phases of adjustment, although the permanent, forced nature of the refugee migration experience makes their integration into society more difficult.20,21

There is a paucity of systematically collected data on health statistics as they relate to migration history.22 Most available reports are of small studies, each with its own objectives, methods, and measurement strategies, dissimilar from the others. One review has summarized some of the apparent trends in health due to migration, specifically migration within the European Union.22 The quality of individual studies reviewed, in particular sampling strategies, which might suggest that results are representative of the population under investigation, was not addressed. With this limitation in mind, that review suggested that there are trends towards a rise in tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, cardiovascular diseases, and certain cancers in immigrants. It also suggested that there are a greater number of avoidable accidental injuries at work and at home. Another study suggested that communicable disease prevalence is high in certain immigrant population groups.23 Also reported are difficulties in communication, problematic interpretations of patient symptoms, lack of healthcare provider understanding of traditional remedies for common ailments, unemployment, depression, and underutilization of services.24,25

Psychosocial problems appear to be common and may result from resettlement policies stressing geographical dispersion of migrants to areas where there are few ‘like’ community members in an effort to quickly integrate them into mainstream society. Separation and divorce are reported to be frequent.26 Additional family difficulties are said to occur if children are seen to be integrating more quickly than their parents by acquiring the language skills of the new country resulting in a capacity to more easily function in the new society, with a shift in power from the parent to the child.

Refugee women’s health during resettlement

As with studies of migration and health generally, many studies of resettling refugee women’s health have also been small, and, for the most part, did not define ‘refugee’ consistently nor did they rely on representative sampling or make a direct comparison between refugee women and their host-country counterparts. These limitations preclude drawing conclusions with regard to the prevalence of health concerns within the population of resettling refugee women and their relative importance in comparison to host-country women. They do, however, suggest health issues that should be considered with regard to refugee women. These include: conflicts arising in women concerning control of their own sexuality,27,28 perinatal health,29 the reintroduction of female circumcision,14 mental health,30 health service needs, occupational health risks, and discrimination.

Many immigrant and refugee women are reported to have difficulty controlling their sexuality.27 There is a great deal of confusion with regards to the maintenance of virginity, with family values and those of the new society often clashing.28 This can lead to requests for hymenal reconstruction by some women who are expected to be virgins when they marry and must provide evidence of this through blood-stained sheets. Girls may suffer a fear of being put to death if it is determined that they are not virgins.28 Women from some African countries are not taught or socialized to say ‘no’ to sexual advances by their husbands.27 This stands in stark contrast to many refugee-receiving countries in which a woman may refuse her husband’s advances and if he forces himself on her, he can be charged with rape. If women suggest the use of condoms to husbands having extramarital affairs, this can lead to violence by the husbands towards the women. These women risk being abused in their attempts to protect themselves against STIs and unwanted pregnancies. Infertility or sub-fertility is also thought to cause a great number of problems, especially in groups in which fertility gives rise to social standing.

Perinatal health outcomes are cited as an area of concern.29 Infants born to migrants from certain countries have been reported to be of lower birth weight, shorter gestational age, and to experience higher perinatal and postneonatal mortality than infants of nationals. Only limited reference has been made to other areas of reproductive health. Nutrition, including breast-feeding, was cited as another area of concern. Initiation and continuance of breast-feeding is thought to be decreasing in migrants31 and nutritional problems in their children are reported to be common.

Female circumsicion is being reintroduced into Europe and North America by certain immigrant communities. The Centers for Disease Control in the US, for example, estimates that approximately 168 000 girls and women living in the US in 1990 either had or may have been at risk for female circumcision. An estimated 48 000 of these were under 18, and about 75% of these were born in the US.31

Several mental health issues have been cited as important to resettling refugee women. These include anxiety, depression, somatization, social isolation, and domestic violence.32 A review of childbearing and women’s mental health noted studies reporting psychiatric disorders during pregnancy and postpartum.33 In addition to other psychiatric disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder was reported.

Inadequate health services due to language barriers, or inappropriate sex or culture ‘matching’ between a woman and her care provider have been reported.27,28,32 General health services delivery issues relevant to resettling refugee women are reported to include: general attitudes toward disease, attitudes towards receiving care by male healthcare professionals, and religious taboos.28

Occupational health issues are another area to consider. Refugee women may be employed in certain types of industry for which they are overqualified and in which the general health risks are important due partially to poor protection by employers.30 Some of the general health issues include repeated movement injuries, eye, lung, and skin exposure to toxic substances, long hours of factory employment followed by long hours of home care, and accidental injury.30 Foreign-earned educational credentials, which some refugee women may possess, are an asset to the receiving society in terms of the knowledge base gained.27 They can, however, lead to psychological problems in women due to the drop in social status when those credentials are not recognized by the receiving society.30 Unfamiliar environments may pose very real challenges to resettling refugee women. Even household items such as dishwashers and fireplaces and practices such as usual garbage removal may need to be explained to women.27 Discrimination based on color, physical features, or race is another issue that must be dealt with by many refugee women,27 not only in the workplace but in every aspect of their lives.30

Summary

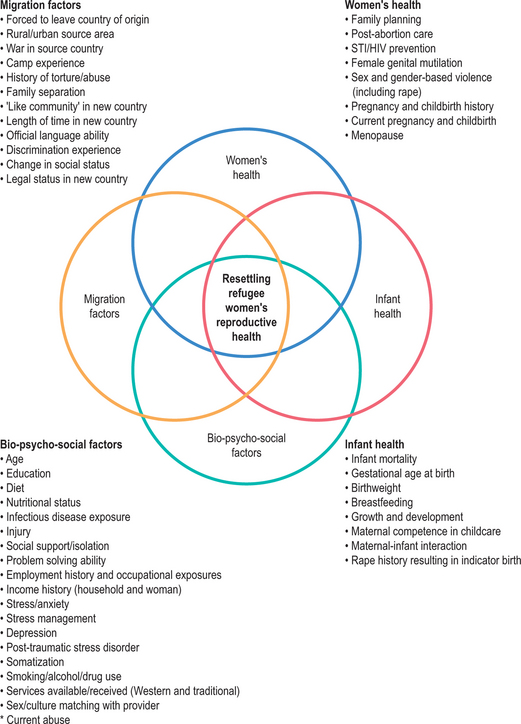

Studies reviewed on resettling refugees suggest health concerns to consider with regard to women’s reproductive health; however, they do not provide insight into the extent to which these health concerns prevail across various refugee populations. The studies reviewed were, for the most part, unsystematic and uncritical reviews, published reports, or case reports, which provide insight into the particular situations of certain individuals. Well-conducted population-based studies are required to provide an estimate of the prevalence of reproductive health issues of concern in resettling refugee women and their relative importance when compared to nonrefugee host-country counterparts. The literature reviewed thus far suggests that there may be several reproductive health-related factors to consider with regard to resettling refugee women. These are summarized in Figure 44.1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree