CHAPTER 43 Women’s Health Issues

Introduction

The rich patchwork of American immigration history continues into the twenty-first century with a polyglot population unique in its ever changing diversity. This chapter cannot possibly review the cultural, religious, and political nuances of women’s immigration journeys as they meet daily with clinicians in hospitals and clinics. Instead, it will ask the reader to become familiar with the particular immigrant group/groups within their catchment community and that they gain knowledge in language, customs, religion, beliefs of wellness, illness, and the role of a woman in that culture from such texts as Transcultural Aspects of Perinatal Health Care,1 Cultural Diversity in Health and Illness2 and, often more interestingly, the clients themselves. A range of issues that are important to women when they meet care providers will be discussed, with the idea of increasing communication and understanding of the woman as an individual within a system of healthcare that should be flexible to her unique needs.

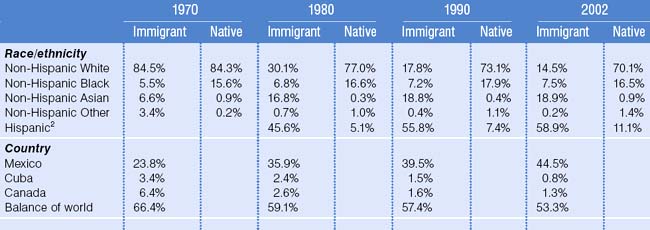

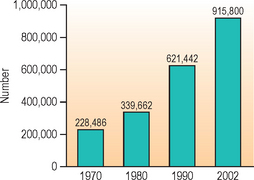

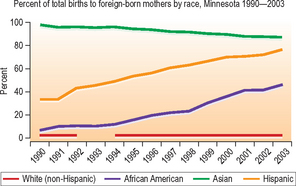

Immigrant mothers represented 21.4% of all births in the US in 2002 (Table 43.1; Fig. 43.1),3 with the number of births to immigrant mothers increasing dramatically since 1970.4 An increase continues into 2005, as shown by data from Minnesota (Fig. 43.2), representative of a national trend with women of Hispanic origin having the highest birth rate.

These words are an explanation given by a small Asian woman looking up at a tall, white-coated OB/GYN resident physician. The physician found it unacceptable that the pregnant woman did not want to be examined by him at a 36-week prenatal visit. In an effort to help the physician understand this woman’s need of respect for her modesty and of a female provider, the woman had agreed to explain her wishes via an interpreter. Had the young physician had previous exposure in care of immigrant women, he may have known that touching certain parts of the body is considered disrespectful or insulting to the Hmong and he would have been more aware of the factors which contribute to the response of any immigrant to life in his or her adopted country. This Asian woman, born in the mountains of Laos, was shaped by the belief system of her Hmong childhood. Married as a teenager, she had delivered her first son and daughter at home with assistance from her mother-in-law and husband. She fled from the Pathet Lao soldiers through the jungles of Laos, crossed the Mekong River to a refugee camp and then adapted to resettlement in the US. She had endured the deaths of her son and mother-in-law in the jungle then carried seven other pregnancies, delivering them without complications. Obstetrically, she presented as high risk for grand parity and age. Her strengths, however, were her innate knowledge that she could carry and deliver healthy babies. Motherhood is highly regarded within her family and community, and if she continued the rituals of pregnancy long used by her community, they would keep the pregnancy safe. On the day in mention, she was noted to be wearing new white strings and a copper bracelet around her wrists denoting that the traditional shaman ceremony – Ua neeb – had taken place in preparation for safety and well-being in labor and birth.

In whatever group, immigration is an overwhelming and stressful experience. The American Refugee Committee in 1990 described stages of adaptation which included euphoria, hostility, recovery, acceptance of, and then integration into a new country. Integration can be rapid in women who are young and come from stability. In older women, or those with a turbulent background, integration can take many years, if it ever happens. When a clinician first meets an immigrant, it is helpful to an ongoing relationship to take time establishing both an immigration and resettlement history. In a first prenatal encounter, many clues to the history await an enquiring examiner. Openness to the first greeting and questions, willingness to undress for the examination, stillness and/or rigidity of expression and/or body in response to touch, acceptance of testing, medication, and repeat appointments will tell of the level of trust and engagement any one client will allow. Declining the same may require bartering by clinicians to meet agreed acceptance with examination and testing deferred until the client can accept with understanding.

Modern obstetrics has benefited from the advances of medical science and research, yet there is a paucity of high-quality population-based studies on refugee women’s reproductive health.3 Immigrant and refugee women are placed together in national data collections with women of the same ethnic background who can be third- or fourth-generation Americans. Indeed, newly arrived African women are placed in the same data base as women whose American roots are centuries old. ‘For statistics to be meaningful, we need to take a closer look at each subgroup.’ ‘Our challenge for the next century is to close the disparities gap without compromising the uniqueness and richness of each culture.’4 The conclusion of a 2005 study of adverse pregnancy outcomes among Somali immigrants in Washington State echoes Dr. Satcher’s words, namely that pregnancy outcomes should be evaluated within ethnically and culturally unique groups. Somali immigrants were found to be a high-risk subgroup.5

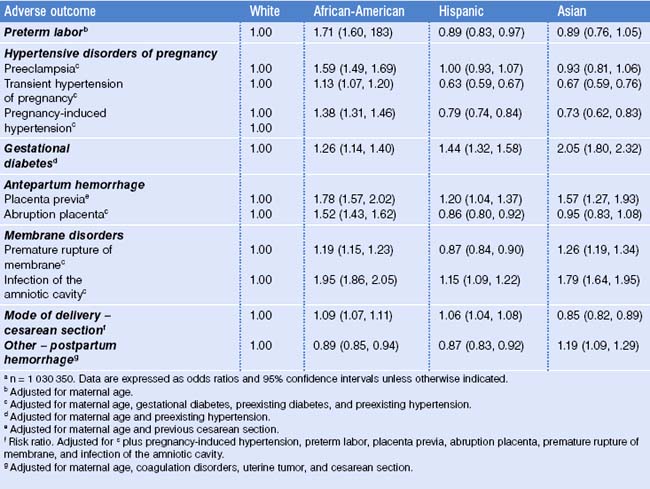

Engagement and partnership in care are essential if the reduction in maternal mortality and morbidity, the Healthy People 2010 goals,6 are to be achieved. Evident in Table 43.2 are the adverse outcomes well known to clinicians in obstetrics who daily strive to prevent acute occurrences. Frequently, it is only when the acute occurs that many immigrant mothers will engage in the care that is appropriate. In the interchange between clinician and patient in a clinical setting lie the seeds of change in maternal statistics.

Physical Examination

The importance of a physical examination is basic to all Western medicine, where the clinician undertakes a full physical examination. Jennifer Potter7 writes of a lack of knowledge, fear, cultural beliefs, restrictions, taboos, history of sexual abuse, personal violence, or a lack of familiarity or belief in preventive screening as barriers to examinations by women. She gives pointers to performing a sensitive exam which include building rapport, attending to comfort, respect for modesty, and empowering the patient before, during, and after the exam by explanation in simple nonmedical language. Her outline for examination is particularly relevant to women who have a history of rape, violence, or female circumcision.

Tips for performing a sensitive and comfortable pelvic examination

Traditional Practices

Traditional practices such as cupping, coining, and pinching (Figs 43.3, 43.4, 43.5) are frequently seen during examination. Used prior to a clinic visit to give comfort or alleviate symptoms, they show a belief in complimentary healing. Pinching between the eyebrows may relieve headache, coining on the soft tissue between ribs is believed to reduce fever. The resulting dermabrasion, which lasts several days, should not be confused with bruising from domestic violence. Ritual skin decoration and tattooing of face, breasts, and abdomen, performed as rites of passage into womanhood, can be observed in women from Africa.

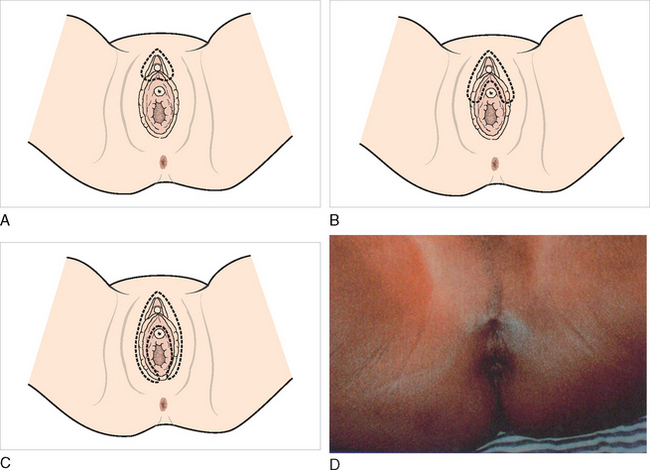

Female circumcision

Female circumcision (Fig. 43.6) is most commonly performed in Africa, with 98% of all women in Sudan and Somalia being affected,8 as well as the Middle East and Asia – all areas from which women migrate to the US. Clinicians therefore will be required to observe and treat the long-term effects of circumcision with an understanding that the circumstances under which the ‘procedure’ was done may not have been conducive to accurate cutting. The end result, then, in any one woman may have features of different types of circumcision, the most common types being:

Long-term complications of female circumcision2

Problems for prenatal care and labor

Prior to examination, it is important to ask a patient if ‘cutting’ has taken place, the woman’s feelings on the matter, and whether a previous pelvic examination had been undertaken. The patient’s knowledge of the type of circumcision may not be accurate and clinical assessment can decide the extent of cutting, and need for defibulation or reduction of circumcision.

Opportunities to discuss and encourage deinfibulation should be taken as they present, which could be pre-marriage and pre-pregnancy, 20–30 weeks’ gestation in pregnancy, or at birth. The clinician involved must have an understanding of the highly personal, sensitive, emotive, and individual response to such discussion and allow time for it to unfold. As with many facets of childbirth, in whichever culture, stories abound over what should or should not be done to the vulva and perineum during birth. Circumcised women know by oral tradition of the fistulae that can result from obstructed labor, with resultant incontinence of urine and feces so destructive to women’s lives.9 What they have not yet come to trust is modern obstetrics’ ability to recognize and resolve obstructed labor in most cases not caused by circumcision.10

Counseling regarding defibulation

Prenatal visits allow time for discussion and agreement on deinfibulation with complete or partial repair of the incision. Many circumcised women feel their closed appearance is normal and that to be opened would be abnormal. International research has looked at the medical consequences of the physical act; only now is research beginning to look at the psychological and emotional impact of female circumcision and deinfibulation on the woman’s body image. K.E. Adams writes that ‘until cultural factors that lead to circumcision are understood, the pattern of abuse will continue.’11 Clinicians must discuss the issue with women who have daughters in the hope that opening the subject to debate will bring pause or cessation to this custom passed from generation to generation. The clinician can also discuss the law as it stands in the US related to female circumcision by which the practice became a federal crime in March 1997 (Table 43.3).

Table 43.3 States that have enacted legislation criminalizing female circumcision

| Californiaa | Minnesota | Rhode Island |

| Delaware a | New Jersey | Tennessee |

| Illinois | New York | Texas |

| Michigan | North Dakota | Wisconsin |

a These states have also enacted legislation that criminalizes both the parents and the physician who perform female circumcision.

Obesity

As female circumcision is of international concern, so obesity is one of the fastest growing national health concerns in the US with one-third of all women considered obese. Obesity has been found to be more prevalent in lower income and minority women, with 49% of African-American women, 38% of Mexican-American women, and 31% of white women found to be obese.12 Associated disease leads to greater morbidity and when coupled with pregnancy, leads to higher rates of miscarriage, type II diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, and macrosomia.13 Yet in new immigrants, obesity is shown as an 8% prevalence in those with less than 1 year’s residence in the US. This rate doubles to 19% with a residency of 15 years and over. Kaplan and colleagues14 noted a nearly fourfold greater risk of obesity in the Hispanic population between recent immigrants and those of longer term. Being heavy is considered to be a sign of well-being and prosperity in many immigrant communities.