Vulvar cancer is uncommon. In the United States, fewer than 6,000 new cases are diagnosed each year. Although multidisciplinary practices vary, generally no more than one-third of patients with vulvar cancer have an indication for RT. This means that vulvar cancer comprises an even smaller proportion of RT practice than vaginal cancer.

There is very little level I evidence to guide treatment. Since the Homesley trial,1 most studies relevant to the radiotherapeutic management of vulvar cancer have been retrospective. Many of the patients included in these studies were treated before modern diagnostic and therapeutic standards were available, limiting the relevance of their data to current practice.

The external beam techniques used to treat vulvar cancer are challenging. As discussed in this chapter and in Chapter 5, poor visualization of many vulvar tumors on standard diagnostic imaging studies makes accurate target volume definition difficult. The shape and orientation of the targets and close proximity of critical structures also pose special treatment planning challenges.

Management of the short-term side effects of surgery and radiation is particularly challenging for patients with vulvar cancer. Postoperative complications, infection, and radiation effects can all lead to treatment delays that may reduce the effectiveness of RT. Skilled management of treatment-related side effects plays an important role in achieving optimal results.

The long-term effects of treatments can be severe. Many factors, including postoperative complications, radiation effects, infection, and tissue damage caused by the primary vulva cancer, can have lasting effects on the well-being of patients with locoregionally advanced vulvar cancer. These effects can be minimized through careful integration of multidisciplinary treatments. However, clinicians are still searching for the best ways to balance these treatments, particularly for patients with locally advanced disease.

To determine the extent and resectability of local and regional disease.

To rule out metastatic disease that would change the treatment goal from curative to palliative.

To rule out other primary genital tract cancers. About half of vulvar cancers are human papilloma virus (HPV) related, and these patients are at increased risk for cervical, vaginal, and anal cancers.

To determine whether the patient is medically fit for treatment. All patients require a careful history and complete physical examination before initiation of treatment.

Physical examination: Pelvic examination should include careful inspection and palpation of the vulva and perianal region including rectovaginal examination to determine the extent of local disease and proximity of tumor to the urethra, clitoris, anus, and vagina. The cervix and vagina should be carefully examined, ideally with colposcopy, to rule out invasive or preinvasive lesions in those sites. If patient discomfort prevents an adequate assessment in clinic, examination under anesthesia (EUA) should be performed; if there is periurethral disease, cystourethroscopy should be performed. In cases of locally advanced disease, both the gynecologic oncologist and radiation oncologist should be present at EUA if possible. In selected cases (particularly those with vaginal involvement), interstitial placement of fiducial markers can assist in subsequent radiation treatment planning (CS 12.3). All clinical findings should be carefully documented, with detailed descriptions of the location and morphology of abnormal lesions and estimates of tumor diameters and the distances between tumor and perineal structures. Examination should also include an assessment of the groins, although even extensive lymphadenopathy can be missed on physical examination (CS 12.8).

Ultrasound: In experienced hands, ultrasound combined with ultrasound-directed fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology has a better than 90% sensitivity for detecting nodal metastasis (Chapter 4).2 In one study of 40 patients, Moskovic et al.3 correctly identified metastatic nodal disease in 11 of 13 groins; the two false negatives were in nodes with metastatic deposits <3 mm. However, the sensitivity of ultrasound undoubtedly varies with the experience of the ultrasonographer and, even in the most experienced hands, a negative result is insufficient to rule out the need for groin treatment in patients with invasive cancers. Ultrasoundguided FNA may, in selected cases, help to guide the dose of radiation given to equivocal nodes; however, if there is any doubt, suspicious nodes that have not been removed should be treated as if they were positive, because the price for error is high (CS 12.1). Ultrasound is also a noninvasive, inexpensive method for following the groins of patients after negative results for sentinel node biopsy if a complete dissection has not been performed (CS 12.10).

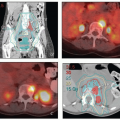

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT): Although CT is generally superior to physical examination for the detection of lymphadenopathy, it cannot detect micrometastases. Also the infections often associated with vulvar cancers can cause inflammatory nodal enlargement, reducing the specificity of CT. CT can be valuable for detecting extrapelvic metastases but rarely provides useful information about the extent of disease in the vulva.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): MRI provides much better soft tissue detail than CT and can therefore be very helpful in assessing the extent of disease in the vulva and vagina. It is particularly useful in cases of locally advanced disease, where MRI can assist in the determination of resectability. MRI is often very helpful in radiation treatment planning, particularly if the study can be obtained in the treatment position. However, MRI cannot replace a careful physical examination. In particular, MRI frequently underestimates the extent of mucosal involvement in the vagina and, in some cases, fails entirely to detect even fairly extensive vulvar tumors (CS 12.8).

Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT: Studies of the ability of PET-CT to detect inguinal metastases from squamous carcinomas of the vulva have reported sensitivities that range between 50% and 70% and specificities that range from 60% to 90% (Chapter 4).2 Inflammatory nodes are frequently FDG-avid. PET-CT can sometimes be helpful in the designation of RT target volumes in patients with advanced disease.

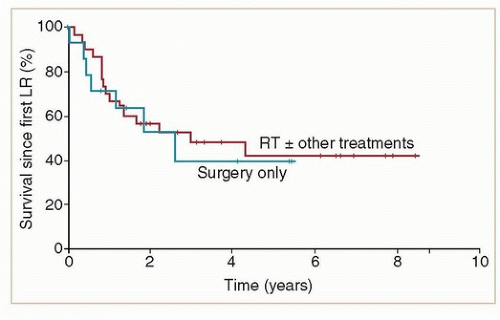

(3 to 141 months), suggesting that many of these recurrences represented new cancers in a high-risk field. Although recurrences were frequently localized to the vulva, 72% of the 29 patients who were treated for local recurrence had a second recurrence in the vulva. The authors of this study did not discuss the effect of local recurrence on survival.

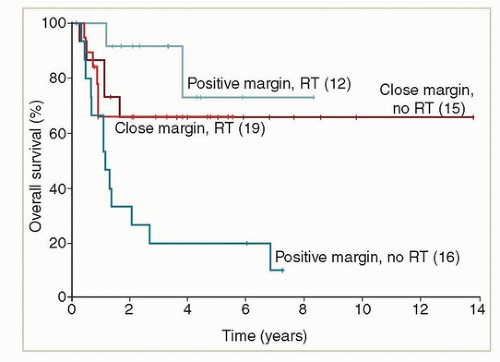

Positive resection margins

Local recurrence <1 to 2 years after primary resection, particularly if other high-risk features are present.

Margins <5 mm, particularly with tumor >3 cm, deep invasion or positive lymph nodes

Multifocal disease or local recurrence more than 2 years after resection with other high-risk features

Margins 5 to 8 mm, particularly with tumor >3 cm, deep invasion or positive lymph nodes

Margins >8 mm but tumor >3 cm, deep invasion or positive nodes

Margins >1 cm, tumor <3 cm, superficially invasive (<2 to 3 mm), negative nodes

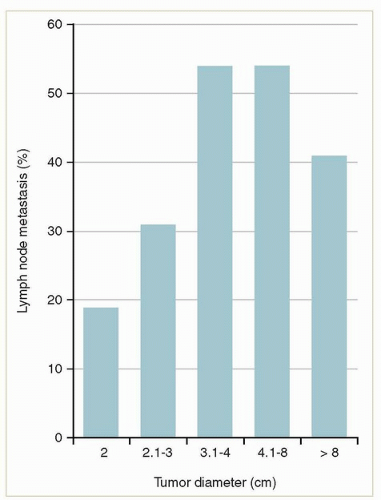

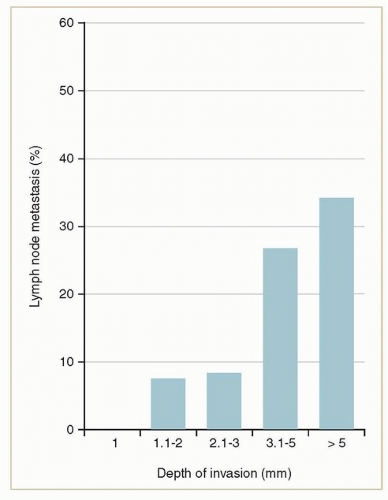

to the tumor to the deepest focus of invasion) (Fig. 12.5).2 Only small tumors that invade <1 mm (stage IA) can be considered to have a negligible risk of lymph node metastasis. The risk rises steeply as the depth extends beyond 1 mm.

In 1994, FIGO moved to a surgical staging system with categories based on radical local excision and, after 2009, complete inguinal lymphadenectomy. This makes it difficult to categorize patients who are treated with lesser surgical procedures combined with radiotherapy or with radiotherapy alone.

The grouping of pelvic node metastases and hematogenous metastases together in the stage IVB category underestimates the curability of patients who have pelvic node disease.20

Although the 1994 and 2009 classifications improved the predictive power of the FIGO classifications, the three systems are so radically different that they cannot be readily translated from one to the other. This has made it extremely difficult to interpret stage designations in retrospective studies of vulvar cancer, most of which cross these historical divides (Chapter 2).

TABLE 12.1 Evolution of the FIGO/AJCC Staging System for Vulvar Cancer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The risks and benefits of various treatment options for the primary site.

The risks and benefits of various treatment options for the nodes.

The combination of approaches to the primary site and groin that will achieve the best overall chance of cure with the least impact on quality of life.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree