36 Vestibular Schwannomas

Over the past three decades, a shift has occurred in the treatment of sporadic vestibular schwannoma (sVS). Rather than relying solely on surgical resection, noninvasive therapies such as external beam radiotherapy and gamma knife radiosurgery (GKR) have been widely studied and employed as sole and adjuvant management strategies.1–3 The literature has seen a surge in publications addressing the relative merits of less morbid interventions, including rates of tumor control, hearing preservation, and complication profiles. Importantly, developments in our understanding of the pathological characteristics and natural history of untreated sVS have allowed practitioners to more confidently select the most appropriate modality of treatment for their patients.

In the evaluation of sVS patients, it is paramount that the needs and preferences of each patient be taken into consideration. sVS is a benign brain tumor, and as such, treatment decisions should center on the tumor’s impact on the patient’s quality of life. Treatment selection must take into account audiometric studies, interval growth rate, and anatomic parameters such as intracanalicular extension and overall size. Such considerations may influence the decision to employ radiation-based treatment versus open surgery, surgical approach selection, and goals for the extent of resection. Weighing the pros and cons of each option with the preferences of the individual patient offers the best chance of achieving a mutually satisfactory treatment result.

In the evaluation of patients with familial schwannomas, similar due diligence must be applied to ensure optimal quality of life and tumor control. However, given the association of familial tumors with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) and bilateral involvement, such patients can present with additional challenges in management.4,5

Management of Sporadic Vestibular Schwannomas

Management of Sporadic Vestibular Schwannomas

Observation

As a benign brain tumor, sVS can be conservatively managed without compromising the overall survival of a patient. Since the introduction and widespread adoption of MRI, incidentally detected sVS has become more commonplace, with recent evidence indicating an incidence of 0.2% across all imaging scans among asymptomatic patients.6 Because many sVS patients present without symptoms or are unwilling to accept the risks of intervention, observation is an important first-line management strategy. Even for patients who are minimally symptomatic, an initial MRI scan provides an important baseline for future treatment decisions; growth can be documented over time with interval imaging, and, at each stage, a provider can discuss management options should the clinical condition deteriorate.

Despite a rich literature on sVS, there remains an incomplete understanding of the manner in which these tumors actually cause symptoms. Beyond the obvious impact of mass effect on adjacent structures, including cranial nerves such as the trigeminal nerve, it has been observed that tumor size does not always correlate with vestibulocochlear symptoms; more specifically, larger tumors do not always cause hearing loss, whereas patients with smaller tumors may present with hearing loss. Thus, in the absence of intolerable presenting symptoms, tumor size on initial MRI may not be the most reliable metric on which to base treatment planning. Size does not always correlate with symptomatology, nor does it predict tumor growth, potentially leaving patients better served by interval brain scans to document tumor growth.

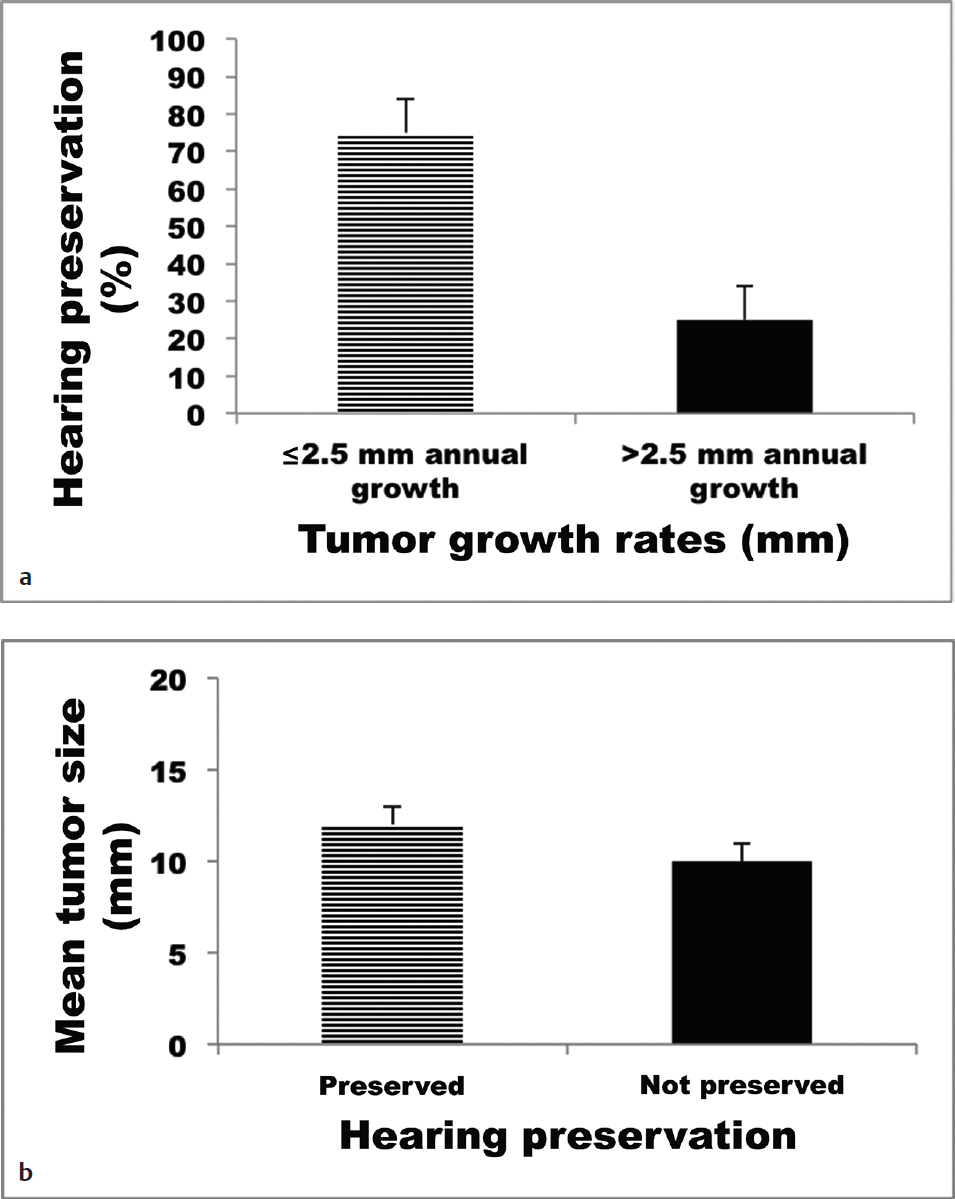

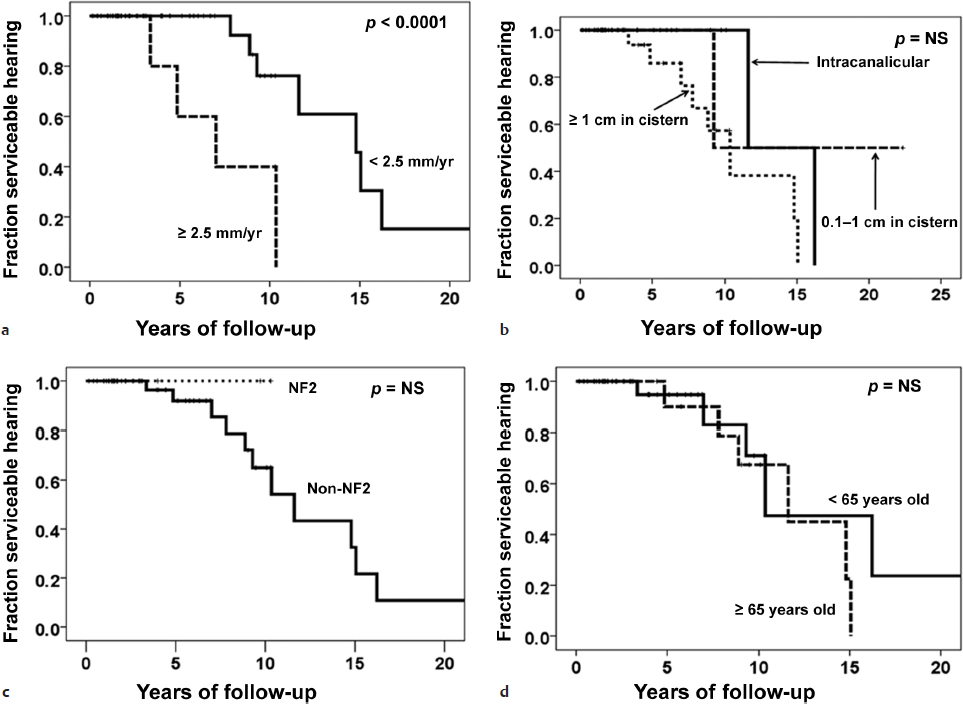

To better document the relationship of tumor growth with patient outcomes, two populations of conservatively treated sVS patients were studied to determine growth rates and their effect on the development of hearing loss.7 These patients included those presenting with serviceable hearing (American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery [AAOHNS] grade A or B) and tumors less than 25 mm in initial diameter. Using a data set of 982 patients observed with interval scans, it was found that patients who experienced growth of greater than 2.5 mm per year were more than twice as likely to suffer hearing loss, whereas initial size had no bearing on the development of hearing loss during the observation period (Fig. 36.1). These results were corroborated by a second study analyzing 59 conservatively managed patients over a 22-year period.8 In this prospectively collected database, patients were at greater risk for hearing loss if their tumors grew more than 2.5 mm per year (Fig. 36.2), with a median time to hearing loss of 7 years (versus almost 15 years in the patients with slower growing tumors). Thus, in the absence of intolerable presenting symptoms, watchful waiting can serve as a viable initial strategy, with the caveat that documented growth rates greater than 2.5 mm per year pose greater risk for hearing loss during the observation period.

Pearl

• Tumor size does not always correlate with symptomatology or predict growth rate.

Hearing loss has been observed in sVS patients followed for more than a decade without evidence of tumor growth on imaging. In these patients, it is possible that pathological characteristics such as microhemorrhage or fibrosis may be responsible for vestibulocochlear damage and hearing loss, potentially prognostic features that are intriguing due to the ability of high-resolution MRI to detect them.9 Further study into the clinicopathological characteristics of sVS will undoubtedly improve understanding to aid the practitioner in counseling patients on conservative versus interventional management.

Special Consideration

• Observation is an important first-line treatment strategy, but patients whose tumors grow at a rate greater than 2.5 mm per year are at increased risk for hearing loss.

Radiotherapy

In a select subset of patients, noninvasive treatment with stereotactic GKR provides an attractive management strategy. Treatment with this modality does not typically require hospitalization and avoids the risks attendant to open surgery. However, radiosurgery is not without its risks, which limits its applicability. Radiation exposure to adjacent neurologic structures can cause tissue toxicity such as cranial neuropathies, whereas other complications such as cerebral edema and hydrocephalus have also been reported. Furthermore, tumors greater than 30 mm in diameter are not currently candidates for single fraction GKR.

As the role of GKR has become better established for benign skull base tumors such as sVS, there has been an effort to identify factors that predict postinterventional hearing preservation, including tumor size, patient age, and radiation dose given. GKR would appear to have excellent tumor control rates largely in excess of 90%, and acceptable overall hearing preservation rates, with numerous studies reporting rates over 50%. More specifically, radiation dose less than 13 Gy is predictive of increased hearing preservation, whereas age and tumor volume have little effect (Fig. 36.3).10,11