Vaginal Cancer

INTRODUCTION

Among the gynecologic malignancies treated with radiation therapy, vaginal cancers pose some of the greatest management challenges. Several factors contribute to this:

Vaginal cancer is rare. Fewer than 3,000 cases are diagnosed per year in the United States. Less than 5% of gynecologic cancers referred for radiation therapy are primary vaginal cancers, and physicians who have nonspecialized radiation oncology practices are likely to see fewer than 10 to 15 cases during their careers.

Vaginal cancers are typically located within millimeters of critical structures. Because most tumors cannot be removed surgically without sacrificing the bladder or rectum, definitive radiation therapy is usually the treatment of choice.

The intimate relationship between the vagina and adjacent structures also means that the therapeutic window for radiation therapy is very narrow. To obtain the best results, clinicians must customize radiation treatment to the specific clinical situation using physical examination and high-quality imaging to accurately define target volumes and avoidance structures for each stage of treatment.

The technical aspects of treatment are highly specialized. Depending on the precise location of the target vis-à-vis adjacent critical structures, external beam and brachytherapy techniques can vary widely. Many of these techniques are very specific to the management of tumors in the vagina.

Treatments often have many components, including intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), concurrent chemotherapy, and brachytherapy. Advance planning for each component helps to minimize delays that could compromise the effectiveness of treatment.

For all these reasons, vaginal cancers are often best treated in large centers by radiation oncologists who have specialized expertise in the management of gynecologic cancers. In any setting, careful planning, attention to detail, and close multidisciplinary collaboration are likely to produce the best outcomes.

Because there have been no randomized trials specific to treatment of vaginal cancers, treatment choices are often guided at least in part by the results of cervical cancer trials. In many ways, vaginal cancers are similar to cervical cancers. Like cervical cancers, vaginal cancers rarely have evidence of distant metastasis at presentation. Nodal metastases follow patterns that reflect the different regional anatomy of the vagina (Chapter 5), but even extensive lymph node metastases can often be cured with chemoradiotherapy. However, with a mean age of 60 to 65 years, women with vaginal cancer tend to be, on average, about 20 years older than cervical cancer patients. About 70% of vaginal cancers are associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection (vs. more than 99% of cervical cancers). Also, different anatomical relationships dictate somewhat different approaches to local treatments of cervical and vaginal cancers.

PRETREATMENT EVALUATION AND STAGING

The goals of pretreatment evaluation are also similar to those for cervical cancer:

To determine whether the treatment intent should be curative or palliative. Patients who have hematogenous or peritoneal metastases from vaginal cancer are rarely curable, but even

patients who have extensive locoregional disease may do well if they are treated with definitive intent.

To define and document the extent of primary disease. This is particularly critical for patients with vaginal cancer because even small variations in the extent and location of mucosal and paravaginal disease can have a major influence on the choice of treatment modality. Documentation of the initial extent of mucosal involvement is extremely important because the final boost must take into consideration the pretreatment disease extent.

To determine the extent of regional disease. Curative treatment depends on an accurate assessment of the volume at risk for regional microscopic disease and accurate identification of enlarged nodes that require an extra dose of radiotherapy.

To rule out second primary cancers or precancers. Women with HPV-positive vaginal cancers are at increased risk for having other HPV-related neoplasia.

To determine the patient’s overall medical condition. It is particularly important to identify any conditions that would influence the patient’s ability to tolerate external beam radiotherapy (EBRT), brachytherapy, or chemotherapy.

To assign a FIGO stage. Although the FIGO classification of vaginal cancers (Table 11.1) has limited value in the selection of treatment or even determination of prognosis, it provides an important means for comparing results in different clinical settings.

Clinical Evaluation

The patient’s initial evaluation should be designed to address these goals as efficiently and accurately as possible. The following studies are particularly useful for assessing the extent of disease in women with primary vaginal cancers:

TABLE 11.1 FIGO Staging of Vaginal Cancer | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

Physical examination

Although modern diagnostic imaging methods are very useful, physical examination is still the best method for evaluating the extent of vaginal mucosal disease. The size, morphology, and location of vaginal lesions should always be carefully documented (see Chapter 4 for more discussion of vaginal examination). If there are multiple lesions, any of uncertain nature should be biopsied to clarify the extent of the gross tumor volume (GTV).

Fiducial markers should be placed at the periphery of the tumor to assist in initial planning, to facilitate monitoring of vaginal motion, and to record the initial extent of disease for subsequent EBRT or brachytherapy boost planning. Because patient comfort and bleeding often limit the quality of examination and accuracy of marker placement, examination under anesthesia is recommended for most cases.

To rule out second cancers, physical examination should always include a careful examination of the vulva, anal margin, and cervix (if present) and biopsy of any suspicious lesions.

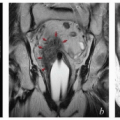

MRI

Pelvic MRI, by far the best imaging study for visualization of tumors involving the vagina, is recommended for most cases. To optimize the study, the radiologist must be given detailed information about the clinical situation and region of interest (Chapter 4). Distension of the vagina with aqueous gel optimizes evaluation of the vaginal walls and tumor contours (CS 11.2, 11.9, and 11.10). When combined with the information from physical examination, MRI can provide a detailed understanding of the extent of vaginal disease that is critical for accurate delineation of target volumes.

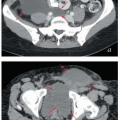

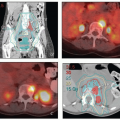

PET-CT

PET is the preferred method for evaluating the extent of regional metastasis and for ruling out distant disease that would change the intent of treatment. Although there are few data specific to vaginal cancer, clinical experience and the similarities between vaginal and cervical cancer suggest that the sensitivity and specificity are probably similar for these two cancers.

Contrast-enhanced CT

If PET or MRI is unavailable or contraindicated for medical reasons, contrast-enhanced CT should be obtained to evaluate the extent of nodal disease. However, even high-resolution CT with digital reconstruction frequently fails to provide useful detail about the extent of disease in the vagina.

In addition, all patients require standard laboratory studies, including CBC, electrolytes, and renal and liver function studies to determine their fitness for treatment.

In summary, detailed pelvic examination is still the most important part of the pretreatment evaluation of vaginal cancer. Modern imaging, including PET and MRI, improves the accuracy of local and regional target definition, potentially allowing safe delivery of more effective doses to gross disease. However, these studies cannot replace a thorough understanding of the regional anatomy, potential paths of local and regional microscopic disease spread, and the influence of internal organ motion (Chapter 5).

RISK ASSESSMENT

Because most patients are treated with definitive radiotherapy, prognostic assessment is usually based on the histologic type of cancer and clinical findings.

Histologic Type

Squamous Carcinoma

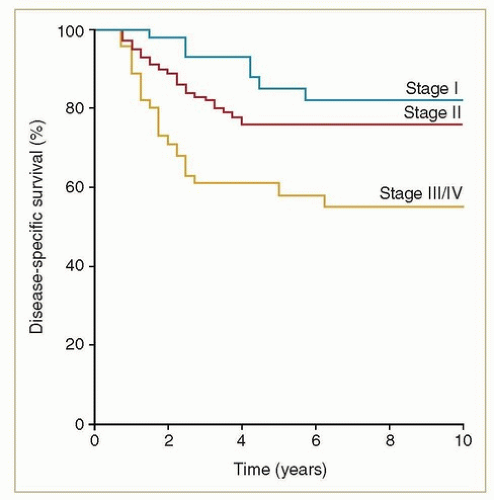

Eighty to ninety percent of vaginal cancers are squamous, and at least two-thirds of these are HPV related. Squamous cancers are usually locoregionally confined at the time of diagnosis, and the potential for cure is high. Even before the use of advanced imaging modalities and concurrent chemotherapy, favorable outcomes could be achieved with definitive radiotherapy. For example, from a review of 193 consecutive women with squamous carcinomas treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center between 1970 and 2000,1 the 5-year disease-specific survival rates were 81% for stages I-II and 58% for stages III-IVA (Fig. 11.1).

DES-Related Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma

In 1971, Herbst and Scully first reported the association between maternal use of diethylstilbestrol (DES) and the subsequent development of clear cell adenocarcinomas of the cervix and vagina in daughters who had been exposed in utero.2 That same year, alerts were disseminated recommending that DES, which had been given to prevent miscarriage in high-risk pregnancies, no longer be administered to pregnant women; registries were established to follow women who had in utero DES exposure or a diagnosis of clear cell carcinoma. Analyses of the resulting data indicated that the peak risk period for development of clear cell carcinoma after DES exposure was between ages 20 and 30; however, case reports and analyses of cancer incidence suggest that an increased risk persists beyond age 40. Exposed women also appear to have a somewhat increased risk of breast cancer after the age of 40. Clear cell carcinomas in the context of DES exposure tended to be diagnosed at an early stage and to have a better prognosis than non-DES-related adenocarcinomas of the vagina.3 Today, women in the exposed cohort are generally aged 45 to 75, so the history of exposure may be difficult to obtain from their mothers.

Non-DES-Related Adenocarcinoma

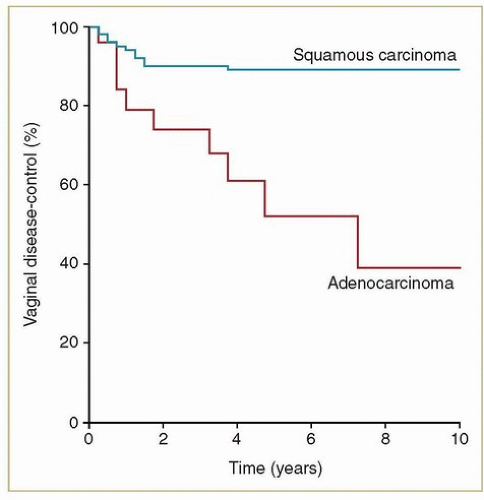

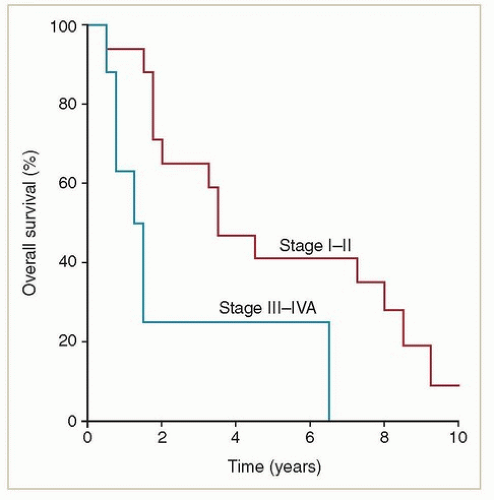

Primary adenocarcinomas of the vagina are exceedingly rare. Most adenocarcinomas involving the vagina are metastases from other sites (e.g., endometrium, ovary, bowel) that must be excluded before a diagnosis of primary vaginal adenocarcinoma is established. Women with non-DES-related adenocarcinomas are, on average, about 10 years younger than those with squamous cancers. Unlike women with DES-related adenocarcinomas, they appear to have a poor prognosis. Frank et al.4 reported results of radiation therapy for 20 confirmed cases of primary non-DES-related vaginal adenocarcinomas treated at MD Anderson; these women had significantly higher local and distant failure rates and poorer survival rates than women with squamous cancers treated during the same period (Figs. 11.2 and 11.3). However, most patients treated during the years of

their study did not receive chemotherapy; its potential influence on outcome is unknown. Although it is difficult to draw broad generalizations about such a rare cancer, analysis of recurrence patterns suggests that these cancers may require somewhat higher radiation doses and possibly more generous clinical target volume (CTV) margins for treatment of primary disease as well as effective chemotherapy to reduce the risk of metastatic disease.

their study did not receive chemotherapy; its potential influence on outcome is unknown. Although it is difficult to draw broad generalizations about such a rare cancer, analysis of recurrence patterns suggests that these cancers may require somewhat higher radiation doses and possibly more generous clinical target volume (CTV) margins for treatment of primary disease as well as effective chemotherapy to reduce the risk of metastatic disease.

FIGO Stage, Tumor Size, and Location

The FIGO staging system for vaginal cancer is based on clinical findings (Table 11.1).5 Patients with FIGO stage III or IV cancers tend to have a poorer outcome than those with stage I or II. However, in two of the largest single-institutional studies,1,6 little difference in outcome was detected between stages I and II. In fact, the distinction between carcinoma “limited to the vaginal wall” and “involving subvaginal tissue” is nearly impossible to make on clinical examination and is difficult even on MRI. As a result, the stage designation tends to be highly subjective and likely difficult to reproduce.

The correlation between stage and outcome reflects at least in part the larger size of higher stage tumors. Several authors1,6 have concluded that tumors larger than 4 cm in diameter have a poorer prognosis than smaller cancers. Frank et al.1 found this correlation to be independent of FIGO stage.

Although, as discussed elsewhere in this chapter, the management approach varies considerably according to the location of tumors within the vagina, there is little evidence of an independent correlation between the tumor site and outcome.1,6 However, as discussed in Chapter 5, the pattern of regional metastasis is strongly correlated with the site of involvement. The tumor site may also influence the pattern of distant metastasis; for example, isolated liver metastasis seems to be more frequent in patients who have extensive involvement of the cul-de-sac or rectovaginal septum (CS 11.6).

Lymph Node Metastasis

Because most patients are treated with radiation alone and only the more recent cases have been evaluated with advanced imaging, there are remarkably few data concerning the incidence of lymph node metastases in women with vaginal cancer. Small lymphadenectomy series suggest that at least 30% of patients have lymph node involvement.7,8 None of the large retrospective studies of radiation therapy for vaginal cancer have addressed lymph node involvement as a risk factor. Although this finding undoubtedly influences the risk of recurrence, even patients who have extensive node metastases can often be cured if they receive adequate doses of radiation to all regions of gross disease (CS 11.2).

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CONSIDERATIONS

The Role of Surgery

Initial primary surgical resection is rarely considered for patients who have vaginal cancer. Small stage I cancers that involve the apical posterior vagina (above the peritoneal reflection) have occasionally been treated with radical hysterectomy, upper vaginectomy, and lymphadenectomy.9 Very small superficial tumors at the apex of a posthysterectomy vagina can occasionally be removed with an upper vaginectomy. However, patients must be carefully chosen; surgery that leaves a positive or close margin complicates subsequent radiation therapy because the region of the positive margin is often beyond the range of intravaginal brachytherapy treatment once the apical vagina has been removed.

The volume and dose of regional treatment are usually based on clinical imaging findings. The arguments for and against lymph node staging or resection of enlarged nodes are similar to those made for patients with other lower genital tract cancers and are discussed in detail in Chapter 3.

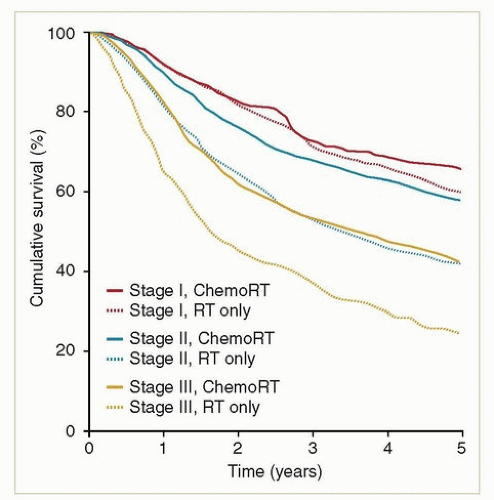

The Role of Chemotherapy

Because of the similarities between vaginal and cervical cancers, it is probably reasonable to apply the results from randomized trials of chemotherapy in patients with cervical cancer to patients with vaginal cancers. Unless there is a medical contraindication, concurrent chemotherapy is generally recommended for all patients with stages II to IVA, some bulky stage I cancers, any patient with evidence of lymph node metastasis, and most adenocarcinomas. The most commonly used regimen is weekly cisplatin. Although there are no randomized studies documenting the advantage of concurrent chemotherapy in patients with vaginal cancer, retrospective studies and analyses of national databases suggest that chemotherapy does benefit these patients10,11,12 (Fig. 11.4).

There is as yet no proven benefit for adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with lower genital tract cancer. However, because

of the high rate of distant metastasis observed for adenocarcinomas of the vagina, we have sometimes offered adjuvant chemotherapy (usually carboplatin and paclitaxel for 4 to 6 cycles) to these patients (CS 11.3). However, the potential side effects of adjuvant chemotherapy and the fact that there are currently no data proving the efficacy of this treatment must be discussed in detail with the patient. Adjuvant chemotherapy is generally not recommended for women with squamous lesions because the margin for improvement over chemoradiotherapy alone is small and the potential benefit uncertain.

of the high rate of distant metastasis observed for adenocarcinomas of the vagina, we have sometimes offered adjuvant chemotherapy (usually carboplatin and paclitaxel for 4 to 6 cycles) to these patients (CS 11.3). However, the potential side effects of adjuvant chemotherapy and the fact that there are currently no data proving the efficacy of this treatment must be discussed in detail with the patient. Adjuvant chemotherapy is generally not recommended for women with squamous lesions because the margin for improvement over chemoradiotherapy alone is small and the potential benefit uncertain.

DEVELOPING A RADIATION TREATMENT STRATEGY

Most treatments consist of at least two phases: (1) several weeks of EBRT encompassing the primary site, paravaginal tissues, and appropriate regional lymph nodes and (2) boost treatment focused on regions of gross disease (GTVs) or other high-risk areas (high-risk CTVs).

A well-articulated treatment strategy for the second phase should always be developed before the first phase is begun. In many cases, the best method for boosting vaginal disease cannot be determined until the patient is re-examined in the 4th or 5th week of pelvic treatment. However, preparations should be made at the beginning of treatment to enable any treatment option(s) that might be considered for the boost. The importance of this cannot be overemphasized. Potentially harmful interruptions in treatment are inevitable if the end of pelvic radiotherapy is reached without any arrangements having been made for repeat imaging, IMRT planning, operating room time, or other requirements (CS 11.7).

If brachytherapy is being considered, the physician who will perform the procedure must be consulted and given an opportunity to examine the patient before treatment and at least once during initial pelvic radiotherapy. MRI or written descriptions of a physical examination performed by someone else a month before the procedure do not provide sufficient information for the brachytherapist to plan treatment. Any misunderstanding of the initial distribution of disease can result in a recurrence; conversely, unnecessary side effects may result if an overly large volume is treated to compensate for inadequate description of the initial disease extent.

Serial clinical examinations are a particularly important part of treatment planning for patients with vaginal cancer. The initial extent of mucosal involvement can easily be obscured by bulky intravaginal tumor but is often made clear as the tumor begins to regress in the 3rd or 4th week of treatment. For boost planning, almost all patients require a detailed re-evaluation after about 40 Gy of pelvic treatment (CS 11.2-11.10). In some cases, physical examination is sufficient to provide an accurate sense of the disease extent. However, if there is any remaining uncertainty about the extent of residual disease, repeat MRI may be helpful.

The goal of radiotherapy is to eliminate gross disease in the primary site and involved nodes, to sterilize microscopic disease in grossly uninvolved nodal and paravaginal sites, and to minimize the dose to normal tissues without compromising local disease control. The balance between the probability of local control and the likelihood of complications is what drives the decision to treat using EBRT only or a combination of EBRT and intracavitary or interstitial brachytherapy.

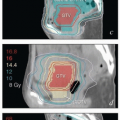

Planning the Initial Phase of Pelvic Treatment

An initial course of EBRT is recommended for all patients who have invasive disease. In general, the vagina and paravaginal tissues should be treated with at least a 3-cm distal margin on gross disease. For bulky lesions, a small integrated boost to the vagina can be used to supplement the vaginal GTV-internal target volume (ITV) to a dose of 50 Gy, while the rest of the pelvic CTV is treated to 45 Gy in 25 fractions (CS 11.2, 11.3, 11.5, 11.6, 11.9, and 11.10). However, if brachytherapy is planned, the external dose to the vagina rarely exceeds 50 Gy. As discussed below and in Chapter 5, the initial nodal treatment volume is determined by the sites of involvement within the vagina and by the presence or absence of gross

lymph node involvement. The recommended dose for at-risk nodes that are not grossly involved is typically 43-45 Gy in 24-25 fractions. Tissues between or immediately surrounding extensively involved nodal compartments may be treated to somewhat higher doses (CS 11.2). Grossly involved nodes are usually treated to at least 60 Gy, but large nodes, particularly those not closely approximating critical structures, may be treated to higher doses.

lymph node involvement. The recommended dose for at-risk nodes that are not grossly involved is typically 43-45 Gy in 24-25 fractions. Tissues between or immediately surrounding extensively involved nodal compartments may be treated to somewhat higher doses (CS 11.2). Grossly involved nodes are usually treated to at least 60 Gy, but large nodes, particularly those not closely approximating critical structures, may be treated to higher doses.

Excellent results can be achieved using standard conformal external beam techniques. However, IMRT holds several advantages for the treatment of vaginal cancers:

IMRT reduces the dose to the central pelvis, which is often filled with bowel in patients who have had a previous hysterectomy.

For distal lesions, treatment of the inguinal nodes can be accomplished with relative sparing of the femoral heads.

If the final boost is to be given using EBRT, IMRT provides a more conformal plan than standard four-field conformal techniques with less collateral high-dose exposure of critical structures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree