CHAPTER 12 US Medical Screening for Immigrants and Refugees

Clinical Issues

Background

Depending on their immigration status, immigrants may undergo medical assessment prior to departure from their country of origin or first asylum. The main purpose of this process is to prevent the importation of communicable diseases of public health significance. This overseas assessment process is detailed in a separate chapter in this text. It may be difficult in the clinical setting to know whether this assessment has taken place, especially with patients who are reluctant to discuss their immigration status. In general, those seeking permanent resident status from outside the US, refugees, and internationally adopted children are most likely to have undergone screening before arrival. In the US, the Federal Refugee Act requires domestic medical screening of refugees to be provided at the state level. Several excellent articles have been published recently which review the screening process for immigrants of all ages and discuss both infectious and noninfectious issues.1–4 This chapter will review the purposes and components of domestic health assessment. Detailed information on screening rationale and strategies for testing for specific diseases found in immigrant populations will be provided. Some information on initial management of positive tests will be presented here; detailed management of these diseases can be found in chapters addressing each condition.

Purpose of Domestic Health Assessment

The goals of domestic health assessment are twofold: to protect the health of the population by identifying and treating communicable diseases, and to ensure the health of the individual immigrant. To accomplish both goals, a complete health assessment that goes beyond screening to focus on the individual needs of the patient is desirable. An approach that combines the use of universal screening with targeted screening for specific groups is optimal. The two groups of immigrants for which there are the most data to inform such a process are refugees and internationally adopted children. Several surveys of specific immigrant groups are also available. For other immigrant groups, such as migrant workers, undocumented immigrants, and short-term visitors, less is known about specific disease risks and susceptibilities. For this reason, this chapter will build the case for evidence-based universal plus targeted screening based on the groups for which the most data are available.

Health screening for refugees entering the US is encouraged after arrival by federal regulations and funds that are available for these programs. The Office of Refugee Resettlement developed a protocol to assist states in the development of health assessment programs5 and has issued guidelines for the use of Refugee Medical Assistance funds for these screening programs.6 Refugee Medical Assistance funds may be available to cover the costs of screening and prevention not covered by existing Medicaid or other state or local health programs. These funds do not extend to immigrants who have nonrefugee status. Experts in the field of international adoption have developed recommendations for assessment of internationally adopted children upon arrival in the US. The requirement for health insurance as a condition for eligibility to adopt internationally makes it easier to provide comprehensive health assessments for these children. For many immigrant groups, however, there are no defined protocols for screening, and financial constraints limit significantly what screening can be done.

There are currently no recognized universal guidelines for screening or assessing the health status of new immigrants. Recommended empiric treatment and screening tests vary widely by state, local clinic, and the immigration status of the individual. There is, however, general agreement in the literature regarding basic elements of the health assessment. These generally accepted elements include a complete history and physical ex-amination, basic screening laboratory evaluation, testing for tuberculosis, immunizations as needed, dental evaluation, hearing and vision screening, and mental health screening (Table 12.1). Other testing and evaluation can be done based on the results of the initial general screening. Healthcare providers caring for immigrants should be familiar with any existing state guidelines and availability of specific screening tests in their area. Each state makes arrangements for screening while some states utilize state or county public health clinics for screening; others contract with private providers.7 Detailed information about public health models for assessing health status on new immigrants can be found in Chapter 11.

Table 12.1 Recommended components of domestic health assessment

The goals of a comprehensive screening program for refugees in Colorado illustrate a thoughtful and thorough approach to screening.8 Seven goals were set out: establish a multidisciplinary team effective in providing health screening and care, establish a comprehensive system for screening, enhance services to provide a full assessment of all refugees, create a system for data collection, enhance provider cultural competency, establish systems for referral and follow-up, and ensure competent interpreter services.

Components of Domestic Health Assessment

History

As with all patient encounters, a thorough history is the foundation on which further evaluation is based (Table 12.2). Though details of the past medical history are desirable, initial questions should focus on the immediate health concerns of the patient, and these should be addressed during the visit, even if it means delaying some components of the health assessment.

Table 12.2 Recommended components of domestic health assessment history

The medical history should include questions about prior surgical procedures, transfusions, history of varicella infection, episodes of jaundice, and hospitalizations. Review of systems should include questions relevant to possible exposures during the course of migration to the US: hematuria (exposure to schistosomiasis), pruritis or limb swelling (filarial disease), skin lesions (leprosy, leishmaniasis), etc. (see Ch. 14, Differential Diagnosis of Ill Immigrants by Organ System). Questions regarding current or past medications should include traditional and herbal remedies and any known allergies. Family history should be elicited if possible, though patients may not have knowledge of specific illnesses of interest such as diabetes, heart disease, or cancer. A complete travel history should be elucidated as many immigrants will have lived in several countries or regions prior to arrival and some will have spent extensive periods of time outside their country of origin. Knowledge about different geographic exposures as well as residence in specific refugee camps can be helpful in focusing the screening process. The social history should include questions about use of tobacco, including smokeless tobacco, alcohol, or other substances as well as questions about current and past family structure. Previous occupational history as well as current occupation, if already employed, may be useful to determine exposures to chemical and environmental risks. For children, school attendance and grade is helpful; for both children and adults assessment of literacy level is helpful. A mental health screen is an important aspect of the history, though may be difficult to elicit before a trusting relationship is developed between the patient and health professional. Psychological stressors can be identified for most new immigrants (separation from family members, moving to a new and unfamiliar place, language barriers) but the presence of stressors alone does not necessarily mean the patient has a mental health problem. Identifying and acknowledging patients’ strengths and coping strategies is often as important as identifying specific stressors. Mental health screening is discussed in detail in Chapter 48.

The history will, in many cases, be obtained via an interpreter. Some centers have interpreter services available to provide a trained interpreter who will be in the room with the patient. Other centers use telephone interpreters. In either case providers should be comfortable working with interpreters and understand that these visits will require extra time and that some concepts of disease may be difficult to translate. In small communities, patients may prefer the use of anonymous telephone interpreters rather than discuss health issues with an interpreter who may be known to them, or is a member of their community. Working with interpreters is discussed in Chapter 6.

Physical examination

A complete physical examination should be performed on all immigrants (Table 12.3). Some individuals may request same-gender providers; eliciting patient preferences for a same-gender provider is appropriate when this is possible. Providers should be sensitive to the fact that this may be the first complete examination for some patients. Examination should include height and weight and, for children less than 36 months, head circumference. Growth parameters should be plotted on the appropriate growth charts for all children and sexual maturity rating should be determined. Note should be made of discrepancies of age based on examination compared with information provided on immigration paperwork. This discrepancy of growth may reflect a true physical state (i.e. secondary to nutritional deficiency) or may be due to mistakes/inaccuracies in documentation. Pulse and blood pressure should be measured. Attention should be paid to the dental and skin examination. Note should be made of scarification and evidence of traditional health practices including female circumcision. Attention should also be paid to the cardiovascular examination for previously undiagnosed murmurs and the abdominal examination for hepatosplenomegaly. Vision and hearing should be assessed during the initial evaluation if possible or persons should be referred to appropriate sites for screening. Pelvic examination is almost never appropriate in the first health assessment visit, unless there is a specific medical indication and the ability to explain in an appropriate setting the reason for the examination and the procedures to be done.

Table 12.3 Recommended components of domestic health assessment physical examination

Review of immunization status and provision of needed immunizations

Immunization records, if available, should be reviewed at the first screening visit. Individuals with refugee status and international adoptees are not required to receive immunizations prior to arrival but many will have received some vaccines and some may have documentation. Those persons with immigrant visa status have been required to show proof of immunization prior to immigration but records should be reviewed on arrival as not all recommended vaccines are available in other countries. Vaccination schedules for routine and catch-up childhood immunizations as well as recommendations for adults are available from several sources. Recommendations are updated periodically and the most current information can be found on the internet from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or from national authorities in other countries.9–11

Vaccines may be accepted as valid if they conform to local standards for age at initiation and interval between doses. History of or examination findings consistent with varicella are considered acceptable but history of other vaccine-preventable diseases is not considered proof of immunity. Serologic screening may be considered prior to immunization as discussed in Chapter 13.

Assessment of dental health

Dental problems are commonly encountered in the immigrant population. Dental caries were the most common finding on examination in pediatric refugees resettled in Portland, Maine, with a prevalence of 16.7% (22/132).12 In Buffalo, New York, 42% of 107 pediatric refugees required referral for dental care.13 Of 1825 refugee children screened in Massachusetts, 62% had dental caries.14 The physical examination should include an oral examination to evaluate for caries, missing teeth, and gingivitis.

Dental care for immigrants is problematic in many areas due to insurance inequities and lack of public assistance dental programs. A detailed discussion of dental health issues in immigrant populations is provided in Chapter 45.

Mental health assessment

Refugees and immigrants have frequently experienced war, trauma, and torture. Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression are the most common psychiatric disorders encountered in these populations. Despite cultural differences, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder may be remarkably similar across populations with hyperarousal, avoidance, and difficulties with concentration and memory being common.4 It may be difficult to initiate discussion of such exposures during the initial screening visits but a detailed history and a mental status examination should be performed as part of a complete evaluation. Attention should also be paid to symptoms suggestive of psychiatric problems with consideration of ethnic and cultural differences of immigrants. A detailed discussion of mental health issues affecting immigrants can be found in a separate section of this text.

Laboratory screening tests

There is some agreement that testing for tuberculosis and hepatitis B and obtaining a complete blood count are appropriate screening tests for all immigrants. Medical screening tests should meet minimum accepted criteria for population-based screening tests: the condition sought should be an important health problem, there should be a latent or asymptomatic disease state, there should be a suitable test (acceptable sensitivity, specificity, negative and positive predictive values), the test should be acceptable to the population, there should be an acceptable treatment and an agreed upon strategy of whom and how to treat, and the diagnosis and treatment should be cost-effective. Laboratory screening tests currently thought to be beneficial in most groups include tuberculin skin testing, complete blood count with differential, serum chemistries including renal function tests, and hepatitis B serologies. Tests most appropriately done in specific groups of immigrants include blood lead testing, serologic tests for parasitic diseases, examination of blood smears (or serum PCR) for malaria, hepatitis C testing, HIV, and testing for syphilis. Tests that are not currently recommended for universal screening, and for which insufficient information is available to direct targeted screening, include testing for CMV, hepatitis A, and Helicobacter pylori. Table 12.4 indicates strength of evidence to support universal testing, and specific groups of immigrants for whom testing may be indicated. The following sections discuss the different screening tests and the evidence to support universal or targeted screening.

Table 12.4 Strength of evidence to support universal versus targeted screening

| Test | Strength of evidence to support universal screening | Specific groups for which targeted screening is appropriate |

|---|---|---|

| Tuberculin skin test | Strong | |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | Strong | |

| Anemia | Strong | |

| Intestinal parasites | Good | |

| Hepatitis C | Poor | Standard risk factors; immigrants from Egypt; Children adopted from China, Southeast Asia, Russia, and Eastern Europe |

| Lead | Poor | Children |

| Hepatitis A | Poor | Those with hepatitis B or C |

| Malaria | Poor | Fever, splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia in those from endemic areas |

| Helicobacter pylori | Fair-poor | Signs or symptoms of disease associated with H pylori infection |

Tuberculin skin testing

Tuberculin skin testing should be performed in all new immigrants over the age of 6 weeks. As rates of tuberculosis among US-born persons decline, an increasing proportion of cases in the US are among immigrants. The proportion of cases in foreign-born individuals in the US rose from 27% in 1992 to 50% in 2002 and continues to rise.15 The highest risk of developing active disease is within the first 2 years after exposure. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection can prevent progression to active disease in most persons. A study of tuberculosis among persons in Manhattan demonstrated that among foreign-born persons most disease is due to reactivation of latent infection, whereas most cases in US-born persons result from recent transmission.16

The World Health Organization estimates that one in three persons is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis worldwide. Based on this estimate, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate at least 7 million foreign-born persons in the US are infected.17 Treatment of active and latent tuberculosis in this population is complicated by the rising incidence of multidrug resistant tuberculosis in the developing world. Providers should have knowledge of resistance trends in the coun-tries of origin of their patients as well as any other regions of long-term residence prior to immigration.

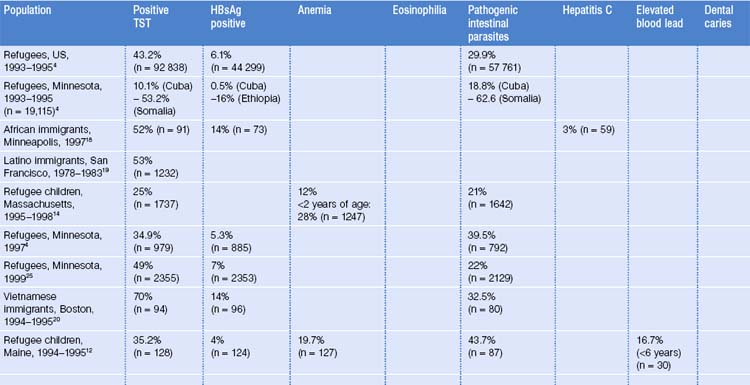

A positive tuberculin skin test is one of the most common findings on screening of immigrants. Of over 92 000 refugees screened throughout the US in 1993–1995, 43.2% had positive tuberculin skin tests.4 Rates ranged from 10.1% to 70% in different groups of immigrants tested (Table 12.5). In Buffalo, New York, 17 of 83 (20%) screened refugee children had positive skin tests.13 In Portland, Maine, 35.2% (45/128) of refugee children were positive.12 A larger study in Minnesota of refugees of all ages found an overall prevalence of positive skin tests of 49% (1145/2355).25 Males, those over age 18 years, and persons from Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa were more likely to test positive.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree