Only approximately one-third of incontinent women have UI or FI to such a degree that they viewed it as a significant bother.[2] Twelve percent of older women report severe or very severe UI. Frequent or severe UI and FI can have a devastating impact on people’s lives, leading to social withdrawal and depression and contributing to the decision to go into a nursing home.[3] Leaking small amounts of urine and/or bowel can often be managed by wearing pads and has only a modest impact on quality of life.

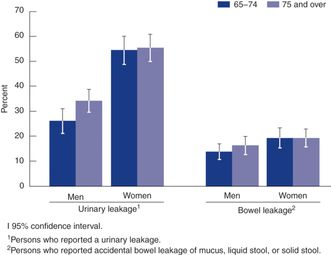

UI and FI prevalence increases with age in older men and women compared to younger age groups (<65 years). Older men may have increases in UI and FI prevalence with age similar to older women, as shown in Figure 27.2. The loss of continence will not always occur with aging. Many specific age-related changes, such as functional impairments in mobility, dexterity, cognition, and reduction in bladder and bowel capacity and sensation, contribute to UI and FI. Other established risk factors that are not age related include obesity and parity in women for UI and FI. The strongest single risk factor for UI in men other than age is prostatectomy or transurethral resection.[2] Stool consistency is a strong risk factor for FI in men and women.

An estimated 60% of people with UI and FI who are identified through surveys have not reported their incontinence to a health care provider,[4] perhaps because they are embarrassed or believe nothing can be done to help.[5] This is unfortunate because UI and FI are curable in many and can be managed in most cases.[6] Health-care providers, therefore, should specifically ask about incontinence.

Physiological mechanism for continence, micturition, and defecation

Innervation of the lower urinary tract system and the anorectal area is under cholinergic, adrenergic, and somatic control. The early phase of bladder accommodation is mediated by β-adrenergic receptors in the bladder dome. Bladder and lower rectal contraction is mediated by cholinergic (parasympathetic) activity, whereas relaxation of the urethral and anal internal and external sphincters is mediated by adrenergic (sympathetic) pathways in the pudendal nerve via a spinal reflex mediated by the S2–S4 sacral nerve roots. Normal bladder capacity is 300 mL–600 mL. Less is known about normal bowel capacity, given the wide variations in compliance of the recto-sigmoid region.

Central nervous system control of bladder and bowel sphincter function is mostly inhibitory; that is, reflex bladder and bowel contractions are actively inhibited until a socially appropriate time and place to urinate and/or defecate is found. This inhibition occurs through neural linkages from the sensorimotor cortex of the frontal lobes to the brainstem, cerebellum, thalamus, and spinal cord. Micturition and defecation normally involve a conscious disinhibition of bladder and/or bowel contractions. Thus, stroke and other neurological processes can result in UI and FI because of loss of central cortical inhibition. Excessive bladder filling may overcome higher cortical inhibitory inputs, resulting in the involuntary contraction of the bladder via the reflex arc (referred to as uninhibited bladder contractions). Less is known about the central process of defecation in comparison to micturition.

The urethra and anus are composed of internal (smooth muscle) and external (striated muscle) sphincters. Somatic innervation through the pudendal nerve allows voluntary contraction of the external sphincter and pelvic floor musculature that protects against urine and bowel loss from sudden increases in abdominal pressure. Voluntary contraction of the external urethral muscle also reflexively inhibits bladder contraction and can interrupt voiding. Voluntary contraction of the external anal muscles can also inhibit bowel wall contraction and delay defecation.

Continence depends on voluntary inhibition of reflex bladder and bowel contraction and intermittent, as needed, voluntary contraction of the striated pelvic floor muscles to counter increases in intra-abdominal pressure. Micturition and defecation require voluntary disinhibition of bladder and bowel contractions, which reflexly leads to relaxation of both the internal and external urethral sphincters.

Classification for urinary and fecal incontinence

Transient incontinence is defined as new leaking of sudden onset that is generally associated with an acute medical or surgical illness or drug therapy, and it is usually reversible with resolution of the underlying problem. “Functional incontinence” is another term that has been used for this condition. Causes of transient urinary and fecal incontinence are diverse (Table 27.1). Drug side effects contribute greatly to this problem; therefore, a review of prescription and over-the-counter medications is extremely important.

Established urinary and fecal incontinence are usually chronic, require investigation, and are amenable to treatment in many cases. There are four types of established urinary incontinence: stress, urge, mixed incontinence, and overflow (also termed “chronic urinary retention” and “incontinence with a high postvoid residual”) (see Table 27.2).

| UI type | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Urgency UI | Often occurs with a strong urgency sensation and uninhibited detrusor (bladder) contraction |

| Large volume leakage | |

| Stress UI | Hypermobile urethra |

| Internal sphincter insufficiency | |

| Reduced pelvic floor musculature | |

| May also be secondary to trauma (e.g., obstetrical) or surgery (e.g., prostatectomy) | |

| Small or large amounts of leakage may occur | |

| Overflow UI | More common in older adults with impaired mobility and functional impairments (e.g., long-term care residents) |

| Usually involves prostatic enlargement in men and prolapse in women | |

| Worsened with medications with anticholinergic side effects | |

| May need to treat constipation symptoms |

Urgency urinary incontinence

Urgency incontinence results from unsuppressed bladder contractions (detrusor instability). These uninhibited contractions are associated with an irresistible urge to void and usually result in loss of a large volume (>100 mL). Patients with urgency incontinence may also have symptoms of urgency, frequent urination, and nocturia, which is called overactive bladder (OAB). By definition, to have OAB, one must have urinary urgency without a urinary tract infection (UTI). “Detrusor hyperreflexia” is a term describing unsuppressed bladder contractions associated with a neurological disorder. Any damage to the structural integrity of the cholinergic inhibitory center of the central nervous system, or the afferent innervation from the lower spinal cord where the reflex arc is located, can cause detrusor hyperreflexia. Processes such as Alzheimer’s disease, cerebro-vascular atherosclerosis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord tumors or transection, and cervical spondylosis (among others) may result in UI by this mechanism.[6]

Stress urinary incontinence

Stress UI occurs in women more than men and results from a hypermobile urethra, internal sphincter insufficiency, or reduced support by the pelvic floor musculature in the bladder outlet. Multiple childbirths, gynecological surgery, and decreased effects of estrogen on pelvic tissues, vasculature, and urethral mucosa are possible causes. Sphincter weakness may also be the result of urethral inflammation, neurological disease, radiation therapy, or α-blocker drugs. In men, stress incontinence may occur following prostatectomy. Patients are likely to complain of losing small amounts of urine with coughing, straining, lifting, or changing posture. Some men following prostatectomy will have constant urinary dribbling.

Overflow urinary incontinence (bladder outlet obstruction and neurogenic bladder)

Bladder outlet obstruction is more common in men than women, and it occurs primarily because of benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) or prostatic enlargement, prostatic neoplasm, or urethral stricture. BPH may result in lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) such as frequency, urgency, nocturia, hesitancy, or weak urinary stream. In women, urethral stricture or severe bladder prolapse may also impede urine flow. In both men and women, partial obstruction may become complete obstruction with the use of anticholinergic or α-agonist pharmacological agents, or with severe constipation. “Atonic” and “neurogenic bladder” are terms describing impaired bladder contractions resulting from low spinal cord lesions, diabetic or alcoholic neuropathy, and/or intake of muscle relaxants, opioids, or antidepressants. The usual clinical presentation of bladder outlet obstruction or neurogenic bladder is constant dribbling or leaking associated with an enlarged, palpable bladder. The physical examination finding of a grossly enlarged bladder is very specific, but poorly sensitive for establishing the diagnosis of outlet obstruction. Patients generally strain to urinate, and voluntarily and involuntarily voided urine volumes are frequently small.

Urge, passive, and mixed fecal incontinence

Types of FI are similar to UI and include urge, passive, mixed (urge and passive), and overflow fecal incontinence. Seepage and staining can also be types of passive fecal incontinence. Seepage can also occur with fecal impaction and severe constipation. Accidental bowel leakage is the preferred terminology to use when discussing FI with patients.[7] (See Table 27.3.)

| FI type | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Urgency FI | Often occurs with a strong urgency sensation to have a bowel movement |

| Liquid stool or diarrhea often associated with the inability to hold stool in the rectal vault | |

| Passive FI | Accidental bowel leakage without the sensation of the need to defecate |

| May not be able to differentiate passing gas from having a bowel movement | |

| May also involve seepage after a bowel movement | |

| Staining may also be a type of passive accidental bowel leakage | |

| Overflow FI | More common in older adults with impaired mobility and functional impairments (e.g., long-term care residents) |

| May also involve seepage or smaller amounts of stool loss around an impaction | |

| Associated with symptoms of constipation | |

| May need to treat constipation symptoms to improve FI |

Fecal incontinence and fecal impaction

FI can result from constipation with stool impaction and may be more common in certain frail, older populations. In a recent study, 81% of residents in long-term care settings had symptoms of constipation and FI.[8] However, the true prevalence of impaction and FI in nursing home residents and home-care settings has not been clearly identified. Since constipation with FI is difficult to diagnose, treatments should target constipation.

Incontinence evaluation

History

Evaluation should begin with a detailed history of the nature, severity, and burden of incontinence and identifying the most easily remedied contributing causes. An incontinence diary for urination or defecation filled out before the patient’s visit is helpful. A history of leakage occurring with specific activities or before/after toileting can also help determine the type of incontinence. Questionnaires may also be used to help determine the predominant symptoms associated with urinary leakage.[9]

Important items of the medical history include data about childbirth, pelvic surgery, cancer, neurological disease, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, pelvic floor radiation, prior hemorrhoid surgery, and previous treatment of UI or FI. Specific questions should be asked about prescription and over-the-counter medication use, alcohol use, and fluid intake, along with food sensitivities (e.g., lactose intolerance). Inquiries should be made about the physical layout of the patient’s residence and whether impaired mobility limits access to toilet facilities. The patient should bring a bag containing all prescription and nonprescription drugs to the clinic so that medications that may contribute to incontinence can be identified.

Physical examination and diagnostic testing

The physical examination should focus on the abdomen and urogenital area and the central and peripheral nervous systems. The abdominal examination is insensitive for a high postvoid residual (PVR) or in chronic urinary retention, but gross bladder distention (e.g., >500 mL) can usually be detected. In acute urinary retention, the distended bladder is a firm, midline mass that originates from the pelvis and is dull to percussion. The rectal examination may reveal fecal impaction, a pelvic mass, external hemorrhoids, or an enlarged prostate gland. It is very important to assess perianal sensation and the patient’s ability to contract and relax the anal sphincter voluntarily. An abnormal clinical sign can suggest serious lumbosacral disease, possibly requiring emergency treatment. In women, a pelvic examination is indicated to assess urethral, uterine, or bladder prolapse and to evaluate the patient for any pelvic mass. A gray, dry vaginal mucosa is suggestive of atrophic vaginitis.

The most important diagnostic distinction is between overflow urinary and fecal incontinence and the other types of UI or FI. Most studies show a poor correlation between the underlying cause and the patient’s symptoms. Urinary and fecal incontinence that results from several causes (mixed incontinence) in older people limits the usefulness of evaluation algorithms based on symptoms and signs alone.[10]

Diagnostic tests for incontinence

Selected tests are recommended for the evaluation of patients with urinary leakage. On initial evaluation, a urinalysis and/or a urine culture, if indicated, should be done. Properly collected clean catch urine is adequate for culture even for nursing home residents,[11] although some persons will require an in-and-out catheterization to obtain an appropriate specimen. Further evaluation may be indicated for older patients with even transient hematuria, as the risk of malignancy is appreciable.[12]

Tests for blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, glucose, and calcium are recommended if compromised renal function or polyuria is suspected in patients not taking diuretics.[6] The PVR urine volume should be measured in all patients with symptoms of incontinence. This can be done by inserting, in sterile fashion, a No.14 French straight catheter into the bladder. Caution is indicated for patients with outflow obstruction, as a single catheterization may cause infection. Alternatively, a bladder ultrasound scan may be obtained 5–10 minutes after the patient has voided. The portable ultrasound scan has been shown to be highly reliable, especially at low and very high bladder volumes.[13, 14] Although the definition of a high PVR is controversial, a volume of 200 mL or more suggests either outlet obstruction or neurogenic bladder and is an indication for further urological evaluation.[15] Clinical tests for stress incontinence in women may be useful if urine leakage is present on pelvic examination. Such tests include a supine cough stress test and other types of pad testing for cough or strain induced urinary leakage.[16]

Laboratory tests for causes of loose stool may include evaluation for infectious causes of diarrhea and malabsorption syndromes (including Clostridium difficile evaluation, fat malabsorption, and the presence of leukocytes). Other testing could involve serum tests to evaluate for celiac disease.

Formal urodynamic testing

After the basic evaluation, treatment for the presumed type of incontinence should be initiated, unless there is need for further evaluation. Further evaluation may be indicated for the following: failure of initial treatment, a history of surgery or radiotherapy, marked prolapse on physical examination, PVR greater than 200 mL, inability to pass a catheter, or patients considering more invasive treatment options who desire further evaluation.[15] Common urodynamic tests that provide more detailed diagnostic information include urine flowmetry, voiding cystourethrography, multichannel cystometrogram, pressure-flow study, urethral pressure profile measurement, and sphincter electromyography.[6]

Specialized tests for fecal incontinence

Specialized testing for FI may be indicated if other warning signs are present, such as hematochezia, a family history of colon cancer/inflammatory bowel disease, anemia, positive fecal occult blood test, unexplained weight loss ≥10 pounds, constipation that is refractory to treatment, and new onset constipation/diarrhea without evidence of potential primary cause. If these symptoms are present, colonoscopy may be needed to evaluate for colonic lesions, mass or obstruction, volvulus, megacolon, strictures, or mucosal biopsy. Abdominal radiographs may indicate significant stool retention in the colon and suggest the diagnosis of megacolon, a volvulus, or a mass lesion. Abdominal ultrasound could be ordered if acute or chronic cholecystitis symptoms are suspected as a potential cause for the change in bowel symptoms.

Evaluation may be needed to identify anatomic abnormalities or factors such as external or internal anal sphincter tears or scarring, rectal sphincter muscle weakness, or pelvic floor dyssynergia. Three types of specialized testing may help with the diagnosis and etiology of FI symptoms.[17] Although findings from these tests may identify specific treatments, few have been evaluated for cost-effectiveness.

1. Anorectal manometry measures internal and external anal sphincter pressure at rest and during contraction. High-resolution manometry may also be considered. Sensation and rectal capacity can also be evaluated with a rectal balloon. Balloon expulsion tests can be used with anorectal manometry to evaluate pelvic floor dyssynergia and other defecation disorders.

2. Two- or three-dimensional endoanal ultrasound evaluates structural defects in the external or internal anal sphincters. Often, scarring or thinning of the muscle layers can also be detected. Endoanal ultrasound is done to evaluate patients with FI.

Treatments for UI and FI

Accurate diagnosis of UI and FI is essential for appropriate treatment. Any cause of transient incontinence identified during evaluation should be addressed specifically. Behavioral, pharmacological, and surgical therapies are all effective in older people (see Table 27.4). It is generally advisable to begin a treatment regimen with the least risk and burden to the patient and caregiver. In all types of incontinence, except those characterized by an obstructive process or poor bladder contractility, behavioral techniques should be considered as first-line therapy unless the patient has a specific preference for another type of therapy.[6]

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree