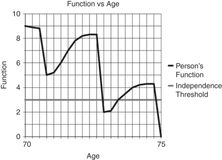

Older person with a high functional reserve who suffers a catastrophic illness.

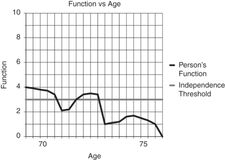

Person with a high functional reserve who suffers debilitating events but is able to recover through rehabilitation.

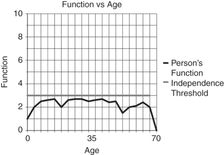

Older person with low functional reserve who declines into a state of dependence.

Person with a significant developmental disability who requires rehabilitation interventions early in life, then periodically during the aging process.

Rehabilitation medicine physicians (physiatrists), geriatricians, and others caring for the elderly often find that there may be no perfect treatment for a disease or functional impairment that comes with aging. Rather, a compensatory mechanism must be found to help restore function. A simple example would be a hearing aid for presbycusis, which does not completely restore hearing but aids the elder in day-to-day interactions. More serious impairments, such as spastic hemiparesis from a stroke, have no simple restorative device and will have profound effects on the person’s function, psychological state, social role, and relationships. The rehabilitation of this individual will therefore be a complex process that will require using a broader biopsychosocial model of medicine.

Impairment, activity, and participation

The World Health Organization provides a contextual framework through the terms “impairment,” “activity,” and “participation” to understand how the loss of a body function affects a person’s ability to care for him- or herself and fulfill a role in society (Table 44.1).[3] The terms “activity” and “participation” have replaced the older terms “disability” and ”handicap,” respectively.

| Term | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Impairment | Loss of body part or function | Broken hip from a fall |

| Activity (disability) | Loss of ability to perform an activity | Inability to walk and perform basic self-care |

| Participation (handicap) | Loss of ability to participate in a life situation | Unable to live independently at home |

A person suffering from a hip fracture from a fall provides an excellent example of how to apply our understanding of the impairment, activity, and participation model as a framework for the rehabilitation process. First, the fracture must be fixed and direct medical consequences of surgery addressed. Second, skilled physical and occupational therapy is employed to improve the activities of mobility and self-care. Lastly, consideration of the person’s motivation, pre-fall and post-surgery functional status, home environment, and caregiver support will determine whether the patient may recover at home or in a short-term rehabilitation facility. Ideally, with successful rehabilitation, the patient may regain full participation in life and return to independent living.

The functional assessment

A physician or practitioner leading the rehabilitation efforts of an elder must first assess and optimize the treatment of any medical problem that may act as a barrier to rehabilitation. For example, cognitive impairments from delirium, dementia, or depression may retard the participation in mobility training and the relearning of self-care skills. Poor cardiac or pulmonary status will reduce endurance and tolerance to therapy. Arthritic joint pain may limit range of joint motion and weight-bearing ability. Other complications of immobility, including pressure ulcers, venous thromboembolism, constipation, urinary incontinence, and disuse myopathy need to be prevented or addressed, as they can limit progress toward functional independence. Once the geriatric medical evaluation has been completed, the rehabilitation practitioner can focus on specific components of the geriatric assessment related to function and rehabilitation potential.

Premorbid functional status

A person’s functional status prior to the onset of an illness or impairment is one of the most important factors in determining rehabilitation potential.[4] If an elder suffers an injury causing a loss of function, rehabilitation can hope to improve the person’s function close to his baseline premorbid functional status. Consider the example of an elder able to walk community distances without an assistive device versus a person confined to a wheelchair due to severe spinal stenosis. If both suffer a unilateral amputation below the knee, the first elder’s prognosis for walking with a prosthetic is good, whereas the debilitated elder’s prognosis for ambulation is poor and would not be a reasonable goal for rehabilitation.[5]

Current functional status

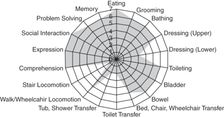

A person’s functional status with a new impairment is the determinant of how much and what type of rehabilitation is necessary. There are many instruments to measure and communicate function, including the Barthel Index and the FIM® Instrument (FIM).[6, 7] The FIM scale is the instrument used by inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs) to measure the amount of assistance a person needs across 18 functional domains. These domains can be divided into five mobility categories, eight activities of daily living (ADL) categories, and five cognitive/communication categories (Figure 44.5).

Graphical representation of the FIM instrument for a cognitively intact elder who has mobility and self-care impairments after a hip fracture.

Each functional domain is scored from 0 to 7, with 0 signifying that the activity does not exist and 7 indicating that the person is fully independent. The terms and definitions that correspond to the numerical scores are part of the normal functional vocabulary of rehabilitation and are useful in describing a patient’s ability to perform any type of activity (Table 44.2).[8]

| FIM score | Term | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Activity does not exist | |

| 1 | Dependent | Person needs 100% help to perform activity |

| 2 | Maximum assist | Person needs 75% help to perform activity |

| 3 | Moderate assist | Person needs 50% help to perform activity |

| 4 | Minimum assist | Person needs 25% help to perform activity |

| 5 | Contact guard stand-by assist | Person can perform activity with someone nearby to prevent fall or to provide verbal cues |

| 6 | Modified independent | Person can complete activity independently with an assistive device (e.g., walker) |

| 7 | Independent | Person completes activity independently |

The FIM instrument can be scored by any trained professional who is working with and observing the patient. For example, a nursing assistant trained in the FIM can score a patient’s toilet transfer activity when assisting the patient, not requiring scoring by an occupational therapist. Typically, the FIM score is the sum of all the measured domains and is measured at the beginning and end of the inpatient rehabilitation stay to quantify functional progress.

Living environment and equipment

A person’s home living environment, including accessibility, is important to establish early in the rehabilitation process. Is the abode one or two story? If it is a two-story house, is there a possibility for a first floor set-up? How many stairs are there to get into the house? Are there handrails? These are just some of the questions that are necessary to determine the functional goals that are achievable to enable a person to return and thrive at home. For a person who is expected to be wheelchair level, plans for a ramp and measurements of door widths need to be done early, in case construction or modifications are necessary. An elder’s current stock of equipment and assistive devices, such as walkers, wheelchairs, commodes, and braces, needs to be assessed with the assistance of therapists for condition, fit, and appropriateness.

Social and caregiver support

The presence of a willing and able caregiver or supportive community of helpers is vital in the rehabilitation process, particularly for elders with major functional impairments. Often, there are limits to what can be achieved during the initial rehabilitation process, so caregivers must be identified early as part of the rehabilitation team, trained, and supported as they care for the elder through extended rehabilitation efforts at home. In the post-acute system, caregivers are important in the following ways: (1) a patient with a caregiver is more likely to be admitted to an inpatient facility for intensive rehabilitation, as the potential for home discharge is greater; (2) in the subacute rehabilitation setting, a person with a caregiver is more likely to return home than be relegated to long-term nursing home care.[9]

The elder’s perception of impairment and rehabilitation goals

Asking elders’ perceptions of why they think they have a functional problem may reveal underlying problems and barriers to the rehabilitation process. For example, a practitioner may assume that a hospitalized elder is not able to walk due to generalized weakness from extended bed rest. Yet when the practitioner asks, “Why do you think it is hard for you get up and walk?” the patient may reveal that he has knee pain from gout. Treatment of the gout will then relieve the pain, which was the major barrier to the mobilization process.

Another important component of the rehabilitation assessment is inquiring about a person’s functional goals. This will assist with assessing motivation and with rehabilitation planning. An example would be asking a traumatic trans-tibial amputee his ultimate rehabilitation goal. If his goal is to be able to jog like he did before he lost his leg, a practitioner will plan for higher-level prosthetic components and intensive physical therapy for gait training. On the other hand, if the same patient feels that he is depressed and has no interest in walking, a referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist and an amputee support group may be a priority.

The rehabilitation physical exam

A comprehensive general geriatric physical exam should be completed; however, in the rehabilitation setting, more focus is placed on the neurologic and musculoskeletal aspects of the exam, as these two systems have the most effect on mobility, self-care skills, and cognitive function.

The rehabilitation team

The rehabilitation of an elderly person can be a complex process, requiring the expertise of multiple therapists and medical professionals. It is incumbent on a practitioner to understand the unique skills of each professional to be able to call on appropriate members to form an effective rehabilitation team. The patient and family are always the focus of our efforts and are considered active members of the team (Table 44.3).

Rehabilitation settings

Multidisciplinary versus interdisciplinary rehabilitation

Rehabilitation of an elderly person can potentially succeed in several different settings, including the hospital, inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF), skilled nursing facility (SNF), outpatient rehabilitation center, assisted-living facility, or in the home. In higher-level rehabilitation settings, including IRFs and some SNFs, the rehabilitation process is carefully coordinated and planned among therapy, medical, and social support services, making the experience an interdisciplinary effort. The group activity of this interdisciplinary team is synergistic, producing more than what the team members could produce separately.[10] In the outpatient or home setting, multiple therapy and medical services are available but usually not closely coordinated, making the experience multidisciplinary rather than interdisciplinary.[11]

Inpatient rehabilitation facilities

IRFs are suitable for patients with complex rehabilitation, nursing, and medical needs, such as a person with a spinal cord injury, amputation, burn, major multiple trauma, traumatic brain injury, or neurologic disorder (such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s disease). Elders who have suffered hip fractures can qualify for inpatient rehabilitation if there is sufficient medical need to remain in a hospital setting. Patients must be able to participate in three hours of therapy a day, five days a week, in at least two disciplines of physical therapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT), or speech therapy (ST). Severely debilitated medical patients with complex medical problems – such as renal failure, recent organ transplant, cancer, or left ventricular assist devices (LVAD) for heart failure – may also qualify if they have sufficient therapy needs to justify intensive rehabilitation. An IRF can be attached to a hospital or be a freestanding facility. Hospital-based facilities have better access to radiology, specialists, and associated procedures such as dialysis. The rehabilitation team is headed by a physiatrist who formulates a detailed treatment plan, visits the patient at least three times a week to address medical and therapy issues, and leads weekly interdisciplinary team meetings that proactively address any barriers to rehabilitation. A typical length of stay is 14 days, with the expectation that the patient’s goal is to return to the community, not to an SNF. Medicare Part A covers inpatient rehabilitation as part of the elder’s inpatient hospitalization days, with an average cost to Medicare of $1,500 a day.[12]

Subacute rehabilitation

Many nursing facilities have beds designated for skilled nursing and rehabilitation, along with long-term care beds for elders needing custodial care. SNFs are suitable for patients with more straightforward or less medically complex conditions, such as hip fractures, elective joint replacements, or debility due to a common illness such as pneumonia or a urinary tract infection with sepsis. In most cases, to qualify for Medicare-covered skilled services, a patient must have a three-day qualifying inpatient hospital stay and skilled nursing needs (IV antibiotics, enteral tube feeds, wound care) or rehabilitation needs in either PT, OT, or ST. Patients typically get one to two and a half hours of therapy a day. A physician must visit the patient upon admission and at least once every 30 days; however, a patient undergoing rehabilitation is often seen one or more times a week by a physician or physician extender. The typical cost of an SNF rehabilitation stay approaches $500 a day.[13] Medicare will cover 100% of an elder’s stay at an SNF for the first 20 days and 80% of the cost thereafter for a total of 100 days, as long as there is a skilled nursing or therapy need. More often than not, a person will improve, plateau with therapy gains, and no longer qualify for Medicare-covered skilled nursing or therapy services before the 100-day mark. At that point, the elder returns to the community or is responsible for covering the cost of custodial care in the nursing home, unless the person has Medicaid or long-term-care insurance coverage.

Home health and outpatient rehabilitation

Intermittent multidisciplinary therapy and skilled nursing can be provided in the home or assisted-living facility if the patient is homebound and has sufficient caregiver support. Each type of therapy or nursing service can visit the patient two to three times per week at home. Once the elder is not homebound, outpatient therapy can provide longer, more intensive therapy, often with equipment not found in the home. Cost to Medicare is in the range of $100–$200 per visit and is subject to Medicare payment caps.

Selecting the rehabilitation setting for the elder

Studies that have attempted to compare rehabilitation outcomes for stroke,[14–16] hip fracture,[17–18] and joint replacement [19, 20] patients in various settings – IRF, SNF, or home health (HH) – do not definitely favor one setting over another. IRFs tended to demonstrate better functional outcomes than SNFs.[14–20] However, the results are confounded by selection bias and lack of uniform functional measurements, and by the fact that many patients will progress through multiple rehabilitation settings. In these studies and in practice, IRF patients have more complex medical and rehabilitation diagnoses, yet are able to tolerate three hours of therapy. SNF patients tend to be older and have cognitive deficits. HH patients are more likely to be younger, healthier, and have good home support.[16, 18]

Fee-for-service Medicare expenditures for post-acute care have risen, reaching $61.2 billion a year in 2011,[12] partly because Medicare reimburses each rehabilitation setting separately each time an elder accesses this service. In an effort to save on costs, Medicare complicates rehabilitation disposition decisions by putting artificial barriers to access – for example, the three-hour daily (15 hours per week) therapy rule for IRFs, three-day qualifying stay for SNFs, and homebound status for HH. Major changes appear to be underway as Medicare is exploring converting to a “bundle” payment system,[21] allowing only one payment for all post-acute and rehabilitation services per qualifying episode. Quality metrics would be in place to prevent patients from receiving inadequate care in the effort to save on costs. A bundled payment system would create financial incentives for providers and health-care systems to find the most cost-effective mix of post-acute medical and rehabilitation care that can produce good outcomes for patients and prevent hospital readmissions.

Geriatric assistive devices

Practitioners often order assistive devices for an elderly person to enhance safety with mobility or independence with self-care. Each device has the potential to help, but its use comes at an increased financial and energy cost. Improper or ill-fitted equipment can also pose a safety hazard that promotes a fall. A practitioner must know the potential benefits and risks of a piece of equipment and seek the assistance of a therapist who can help properly fit the device and train the elder on proper use.

Canes provide an extra point of contact with the ground, adding stability and tactile information about the ground with walking.[23] A simple hook cane is useful for improving walking balance and proprioception, but it can be unstable as the force placed on the handle is not directly over the point of ground contact. A cane with an off-set handle places the handle’s center of gravity directly over the ground contact point, allowing more stable weight bearing. No more than 15% of body weight should be placed through a cane. The cane should be fitted so that the top of the handle comes to about the wrist crease with the elbow flexed to about 15–20 degrees when holding the cane.[23] To off-load a painful lower extremity joint, the cane should be held by the contralateral hand and advanced with the painful limb. Canes can come with foot attachments with three or four points of contact, increasing the cane’s stability, but at the cost of more weight, less natural gait pattern, and potential difficulty with stairs.

Four-point and single-point cane with offset handles. Forearm crutch.

Axillary crutches are rarely used in the geriatric population, as they are difficult to handle, inherently unstable, and may cause axillary nerve compression if improperly used. Forearm or Lofstrand crutches have a cuff around the proximal forearm that allows hands to be free without dropping the crutch. They are easier to maneuver than axillary crutches and are often used for gait training after joint replacement surgery.[24]

Walkers provide a large base of support that can assist in walking stability. With the use of both upper extremities, a walker can help off-load a lower extremity. The disadvantages of walkers are that they can be difficult to maneuver (especially with stairs), promote poor back posture, and decrease arm swing.[25] Standard walkers with no wheels are very stable but require picking up to move forward, which slows down gait and requires significant upper body strength. They may be helpful for people after lower extremity surgery with weight-bearing restrictions or for people with cerebellar ataxia.[25] More commonly, elders use two-wheeled walkers or four-wheeled “rollator” type walkers (Figure 44.7). Two-wheeled walkers maintain a more normal gait pattern compared to standard walkers and can still be used for weight bearing. Rollators may be too easily moved to prevent a fall and therefore cannot be used for significant weight bearing. Rollators are well suited to help elders who need frequent rest breaks or use oxygen, as they often have fold-down seats or baskets to carry oxygen or other personal items.[25]

Two-wheeled and four-wheeled walkers.

A manual wheelchair can be used by an elderly person if she is unable or unsafe to walk, or it can be used to help a caregiver transport a patient. A wheelchair needs to be carefully fitted to the patient by a therapist or wheelchair vendor to maximize its functional utility. Some considerations may include selecting: the proper seat height to allow propulsion with feet along with hands, elevating foot rests for comfort or edema control, detachable arm rest for slide board transfers, specialized seat cushion to prevent pressure ulcers, customized seat back to compensate for postural deformities, and lightweight design to reduce work to manually propel the chair or to lift the wheelchair for transport.[26]

Elders with severe weakness may require the assistance of a power-operated mobility device (Figure 44.8). A powered wheelchair’s benefit of enhanced longer-range mobility at home and in the community must be balanced against the risk of worsening weakness, balance, and endurance from muscle disuse. Motorized systems are costly, potentially difficult to transport, and require extensive documentation for Medicare payment approval. Powered scooters can be a less costly alternative that may be lighter and easier to disassemble/transport, but they have a wider turning radius and fewer seating customization possibilities as compared to powered wheelchairs. Scooters may be difficult to transfer into and cannot accommodate changes that come with progressive functional decline, such as those encountered in patients with multiple sclerosis or amyotropic lateral sclerosis. All powered mobility requires intact cognitive faculties and “behind the wheel” testing and training to ensure safe use.[26]

Motorized wheelchair and scooter.

An assortment of aids to help the elderly with self-care activities can be prescribed, usually with the assistance of an occupational therapist. These include simple devices, such as mechanical “reachers” to pick up objects, dressing hooks to pull up pants, tub benches for safer bathing, and raised commodes to help with toilet transfers (Figure 44.9). For some patients with upper extremity hemiparesis, advanced rehabilitation centers are using more complex mechanical devices. One example is the Myopro™ myoelectric upper arm orthosis, which is a battery-powered arm brace that augments weak elbow flexor and/or extensor muscles to assist in such activities as eating, grooming, and picking up objects (Figure 44.10). Other centers are exploring ways to regenerate organs, muscles, and nerves to restore movement and vital functions. Despite our technological advances, we are many years away from being able to replace the most valuable and versatile aid of all: a human caregiver.

Sock aid, long-handle sponge, dressing hook, reacher.

Myopro™ myoelectric upper arm orthosis.

Rehabilitation of common geriatric problems

Stroke

With over 795,000 Americans experiencing a stroke each year, stroke has become the leading cause of long-term disability.[27] Unfortunately, despite procedural and pharmaceutical improvement in the treatment of stroke, 40% of stroke patients are left with moderate functional impairment and 15%–30% with severe disability.[28] The most common impairments after a stroke include motor weakness, sensory deficits, and problems with speech, language, cognition, swallowing, and vision. Spontaneous neurological recovery mostly occurs within the first three months post-stroke, with the most rapid functional recovery occurring in the first 30 days. Usually, there is very little functional motor recovery after six months post-stroke, but swallowing, speech, and sensory dysfunction may gradually improve over a longer period of time.[29] Some poor prognostic signs include no recovery in the first three to four weeks after a stroke, flaccid paralysis at four weeks post-stroke, severe neurological neglect, severe cognitive deficits, and advanced age.[28] Older stroke survivors may have a poorer stroke recovery prognosis given their increased likelihood of comorbid medical conditions and prior strokes.[30] Units specialized in organized stroke care and rehabilitation provide better patient outcomes for stroke patients.[31] Compared to general wards, these stroke units have demonstrated reduced mortality, improved recovery of mobility and self-care skills, and a greater likelihood of patients being able to return home. These advantages have been found to extend to stroke patients over the age of 75.[32]

A stroke resulting in significant impairments requires an interdisciplinary team for successful rehabilitation. Consider the example of a 70-year-old man with a history of atrial fibrillation who suffers a large right middle cerebral artery embolic stroke resulting in left spastic hemiplegia, hemianesthesia, hemianopsia, neglect, aprosody, dysphagia, and uninhibited neurogenic bladder. The patient has undergone all appropriate testing and lab work, has been initiated on appropriate secondary stroke prevention, and has avoided complications of immobility. A rehabilitation physician or physiatrist performs a medical and functional assessment of the patient and formulates a rehabilitation plan, which would need to include physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, nursing, recreational therapy, orthotics, and social case management. Early in the process, the patient’s and family’s needs and functional goals are explored. This aids in setting appropriate expectations, motivates and engages the patient, and results in improved outcomes.[33]

Motor recovery in hemiplegic stroke progresses in phases.[34, 35] Initially, there is flaccid paralysis and areflexia. Neurologic recovery may be heralded by return of deep tendon reflexes, increased tone, and spasticity. Early voluntary movement may then return in uncoordinated “synergistic” patterns where entire groups of extensor or flexor muscles across multiple joints of a limb co-contract upon initiation of movement. Fortunate hemiplegics may progress to regain functional control of individual muscles and return to normal tone, often in a proximal to distal manner.

Traditional rehabilitation therapies attempt to enhance natural motor recovery and control using physical sensory and motor stimulation, with considerable controversy on whether to promote or suppress synergisms. Rehabilitation also now includes more task-oriented therapy where rehabilitation is focused on acquisition of skills for performance of meaningful and relevant tasks. Programs aim to be challenging, progressive, and optimally adapted to the patient’s capabilities and environment, and invoke active participation to prevent learned disuse.[33] An example of this is constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT), a technique in which a hemiparetic patient uses her weak limb while her strong, unaffected limb is constrained by wearing a mitt. CIMT has been shown to promote cortical reorganization and motor recovery.[35] A practiced form of gait therapy for hemiplegia is body-weight-supported treadmill training (BWSTT), which involves suspending the patient over a treadmill with the therapist assisting in leg movement through the gait cycle (Figure 44.11). BWSTT has shown superior effectiveness over traditional gait training, but requires specialized equipment and significant effort from a therapist moving the paretic leg.[36] Other interventions under study that may prove helpful in enhancing recovery include robotic-assisted motor retraining,[37] functional electrical stimulation,[38] use of neurostimulant medications that augment norepinephrine,[39] and noninvasive brain stimulation using magnetic fields or direct transcranial current to activate dormant brain tissue.[40]

Body-weight-supported treadmill training.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree