Abstract

Intracranial lesions pose a complex dynamic for patients, physicians, and families in terms of treatment, management, and lifetime care. The lesions can be benign and nonoperative to malignant and life altering. An individualized and multidisciplinary approach needs to be instituted for each patient. The care does not end with the surgical intervention or the oncologic therapy. The care is more deeply seeded and involves the whole community. In this chapter we provide a guideline for the overall care of the patient with intracranial lesions.

Keywords

Benign brain tumors, Brain tumors, Intracranial mass management, Intracranial mass surgical intervention, Intracranial tumors, Malignant brain tumors

Background

Tumors of the brain present a special challenge for both patients and physicians. Every year, a new brain tumor is discovered in 6.4 cases per 100,000 persons with an overall 5-year survival rate of approximately 33.4%. Nearly 700,000 Americans live with a primary brain tumor. Brain tumors can occur at any age, but the greatest incidence is with ages 65 years and older, and there is a slightly higher predominance in men than in women. Over a person’s lifetime, there is an approximately 0.6% risk of being diagnosed with a central nervous system cancer. The impact that a diagnosis of brain tumor has on a patient cannot be overstated: some brain tumors can cause significant disability and drastically worsen quality of life, whereas others do not. New treatments offer opportunities to extend life and minimize disability.

Classification

Intracranial tumors are generally classified into either malignant or benign tumors. Furthermore, malignant tumors can be either primary or metastatic. Metastatic lesions are more common than primary tumors. Generally, the proportion of adults with brain tumors increases with age, given that metastatic lesions are more prone to develop over time. The most prevalent brain tumor types in adults are meningiomas, which make up nearly 33.8% of all primary brain tumors ; gliomas (i.e., glioblastomas, ependymomas, astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas) make up almost 80% of malignant brain tumors. Intracranial tumors are often divided into World Health Organization (WHO) classification scale, which can provide patients and clinicians with further information regarding prognosis and management. The WHO scale divides brain tumors into four different classes, from 1 through 4. WHO grade 1 tumors are generally nonmalignant, slower growing, better prognostic lesions. WHO grade 2 tumors are generally nonmalignant but can also be malignant and have a higher propensity for recurrence than grade 1 tumors. WHO grade 3 tumors are aggressive malignant lesions and often recur as higher grade lesions. WHO grade 4 tumors exhibit the most aggressive of lesions and generally exhibit a very high recurrence rate—they demonstrate the poorest prognosis for patients.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of intracranial tumors can vary widely and run the spectrum from a patient who presents with clinical obtundation to an asymptomatic presentation. The location of an intracranial tumor along with its size and mass effect dictates its clinical presentation. Many patients present with clinical signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure: headache, nausea/vomiting, ocular palsies, altered mental status, loss of balance, seizures, or papilledema. Some patients can present solely with one clinical symptom, whereas others present with no symptoms at all. For lesions within the frontal lobe, memory, reasoning, personality, and thought processing can be affected. For lesions within the temporal lobe, behavior, memory, hearing, vision, emotion, and speech can be affected. For lesions within the parietal lobe, sensory perception and spatial relations can be affected. For lesions within the occipital lobe, vision can be affected. For lesions within the brainstem or cerebellum, balance and coordination can be affected. A pituitary tumor can compress the optic nerve and cause a bitemporal hemianopsia. A tumor within Broca’s area can present with expressive aphasia, whereas a tumor within Wernicke’s area can present with fluent aphasia. Meningiomas are dural-based lesions; they are found alongside the dural meninges, and their clinical effects are often related to local mass effect on surrounding tissue. Glioblastomas are very aggressive WHO grade 4 neoplasms with a poor prognosis for recovery. Primary cerebellar lesions that are not metastatic in origin are often hemangioblastomas. Often, such lesions can cause considerable mass effect on surrounding tissue and structures and also have significant surrounding edema as well.

Physical Examination

A thorough physical and neurologic examination should be performed on all patients with intracranial tumors. Neurologic examination consists of a mental status examination with a complete cranial nerve assessment, along with motor/sensory testing, reflex testing, and cerebellar testing. Elements of complex motor system testing and speech and memory testing should also be assessed. As stated previously, the location of an intracranial tumor dictates its presentation. For example, a patient with a tumor present within the motor strip may present with profound contralateral motor weakness, whereas a patient with a pituitary tumor may complain of visual blurriness or generalized hormone discrepancy. A cerebellar tumor may present in a patient with primary gait imbalance, or a patient with hearing difficulty may present with a vestibular schwannoma. A thorough cranial nerve assessment can also provide further clues for the astute clinician in localizing the location and most likely differential diagnoses of intracranial tumors.

Diagnosis

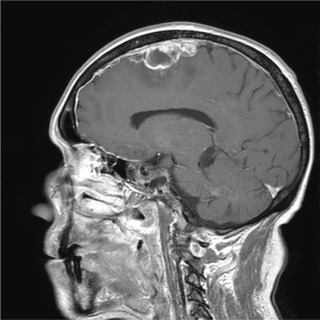

Diagnosis of adult intracranial lesions is generally through a combination of history and physical examination findings, corroborated by imaging support. A clinician approaching a patient with either known or suspected concern for intracranial tumors should collect a thorough history, which often provides clues to the location, duration, and classification of intracranial tumors. In general, a physician will order a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head or a magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain to better evaluate intracranial tumors. The aforementioned imaging sequences provide structural and anatomic characteristics of the intracranial tumors in question, which aids clinicians in generating a differential diagnosis as well as in further management. MR spectroscopy and PET scans offer further clues into the nature of such intracranial tumors, which in turn can aid in making an accurate diagnosis.

For some intracranial tumors, identification of the vascular supply is critical to the subsequent management. These intracranial tumors warrant further vascular imaging, in the form of CT angiography/magnetic resonance angiography (CTA/MRA), as well as venous modalities as well i.e., CT venography/magnetic resonance venography (CTV/MRV). For intracranial tumors that warrant critical vascular findings and close affinity with vascular structures, a diagnostic cerebral angiogram may be necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree