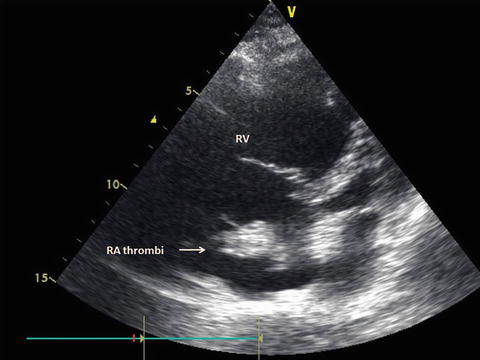

Fig. 1a

Dilated right ventricle in the setting of acute massive PE

Fig. 1b

Dilated right ventricle with large right atrial thrombi

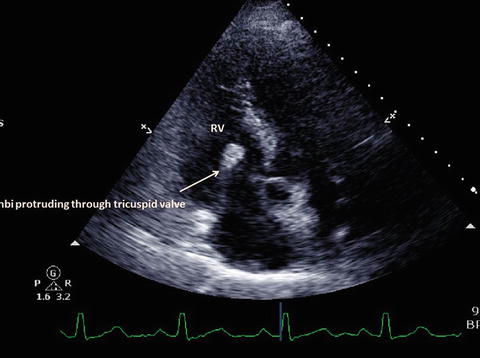

Fig. 1c

Dilated right ventricle with large right atrial thrombi protruding through the tricuspid valve to the right ventricle

Fig. 1d

Dilated right ventricle with large right atrial thrombi protruding through the tricuspid valve to the right ventricle

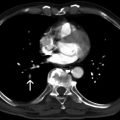

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast medium is the mainstay of the diagnostic workup when clinically possible to perform, and it can accurately diagnose and define the extent of the thrombotic/embolic event. (See Fig. 2, 3 and 4)

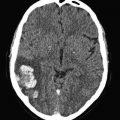

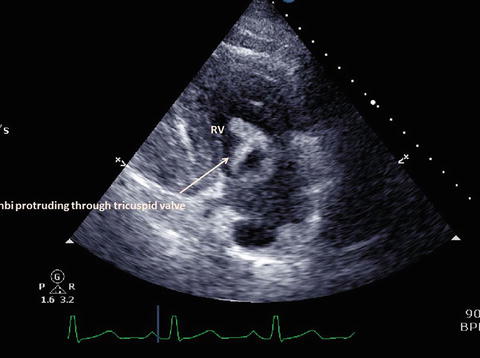

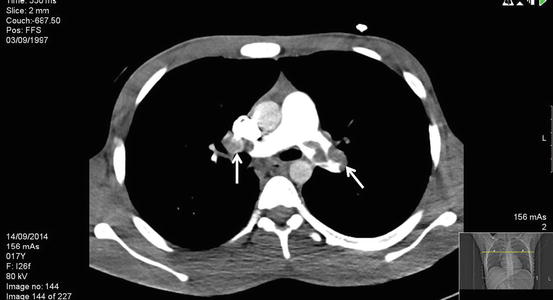

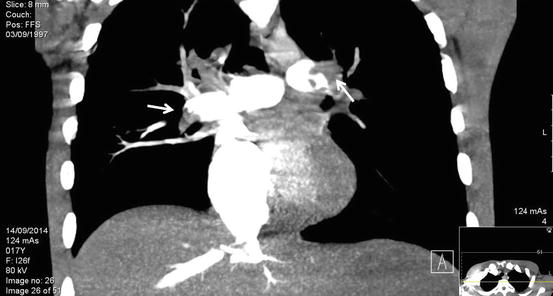

Fig. 2

Axial CT scan demonstrating a left main proximal pulmonary artery thrombus and a more distal right main thrombus (See arrows)

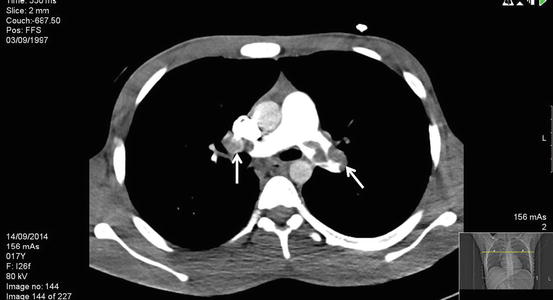

Fig. 3

Reconstructed CT image of Figure 1a. demonstrating a Left main proximal pulmonary artery thrombus and a more distal Right main pulmonary artery (See arrows)

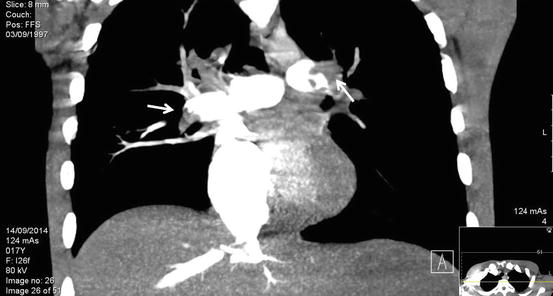

Fig. 4

Axial CT scan demonstrating thrombi in the right and left main pulmonary arteries

Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can identify pulmonary thromboemboli and RV wall motion abnormalities, although rarely performed in the acute setting due to technical difficulties.

Contrast pulmonary angiography is a definitive diagnostic study but is infrequently performed in hemodynamically unstable patients. (Goldhaber 1998)

8 Surgical Indications

Current guidelines published by both the European Society of Cardiology (ESC 2014) and by the American Heart Association (AHA 2011) discuss the indications for pulmonary embolectomy in clinical practice. The ESC guidelines recommend the use of pulmonary embolectomy for patients in whom thrombolysis is contraindicated or have failed as class I, level of evidence C indication, (Konstantinides et al. 2014) whereas the AHA guidelines describe surgical pulmonary embolectomy as reasonable for patients who failed or for those in whom fibrinolysis is contraindicated. (Jaff et al. 2011)

As described in both the ESC and the AHA guidelines, primary reperfusion treatment, particularly systemic thrombolysis, is the treatment of choice for patients with high-risk PE. In patients with contraindications to thrombolysis—and in those in whom thrombolysis has failed to improve the hemodynamic status—surgical embolectomy is recommended if surgical expertise and resources are available. (Konstantinides et al. 2014)

Additional indications may include echocardiographic evidence of an embolus trapped within a patent foramen ovale, or present in the right atrium, or right ventricle (Bloomfield et al. 1988; Ruiz-Bailen et al. 2008).

Proximal emboli are amenable to surgical removal (i.e., right ventricle, main pulmonary artery [PA], and extrapulmonary branches of the PA), whereas distal thrombus generally is not amenable to surgery (e.g., intrapulmonary branches of the PA).

It is important to remember that no large trials prospectively and/or randomly analyzed the effectiveness and outcome of surgical pulmonary embolectomy versus fibrinolysis.

Furthermore, common practice in most large centers focuses on the hemodynamic stability of the patients in order to stratify them to the best treatment of choice. We propose a clinically directed approach which first divides the patients into hemodynamically stable versus hemodynamically unstable patients (Kasper et al. 1997).

Hemodynamically stable patients—a heterogeneous group, which may include either submassive PE (moderate/intermediate risk), and minor PE (low risk) patients. Those with minor/low-risk PE can be treated with anticoagulation. For those with intermediate-risk/submassive PE, therapy should be individualized: thrombolysis and/or catheter-based therapies may be considered on a case-by-case basis when the benefits are assessed by the clinician to outweigh the risk of hemorrhage.

Hemodynamically unstable patients—thrombolytic therapy is indicated in most patients, provided there is no contraindication. Embolectomy is appropriate for those in whom thrombolysis is either contraindicated or unsuccessful (surgical or catheter-based).

9 Embolectomy

Embolectomy can be performed surgically or using a catheter-based technique. The choice between these options depends mainly on available expertise.

Catheter-based modalities—several techniques are available, none has demonstrated superiority over the other. The studies comparing the different techniques are very limited for various reasons, mainly due to different inclusion criteria. Catheter-directed techniques are most commonly utilized in patients with moderate/intermediate risk PE.

The modalities rely on either ultrasound, suction, rotational, or rheolytic technology. Their review is beyond the scope of this chapter, but is should be known that common to all catheter-assisted embolectomy techniques is the risk of pulmonary artery perforation; although rare, it can lead to pericardial tamponade and life-threatening hemoptysis, and is frequently catastrophic. Additional complications include hemorrhage and infection of venipuncture sites, cardiac arrest, and death, as well as device-specific adverse effects.

Surgical embolectomy is discussed further below.

10 Technique of Operation

10.1 Preoperative Management

The preoperative management of patients with massive pulmonary embolism is probably the most critical part, reflecting on the success of the entire procedure. Patient management depends on their clinical status and the level of hemodynamic stability.

In general, this group of patients can be separated into three: Group 1, hemodynamically stable patients; Group 2, hemodynamically unstable patients; Group 3, patients under cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

Group 1 patients should receive high-dose unfractionated heparin (bolus of 5000 IU, followed by infusion of at least 1000 IU/h) once the diagnosis is made. Following that, maintaining adequate oxygenation and cardiac output before establishing CPB is essential. Endotracheal intubation should be established if hypoxemia is present. If adequate cardiac output cannot be maintained with vasopressors, phosphodiesterase inhibitors may be given. Otherwise, if the clinical situation permits, the usual preparations for establishment of CPB should be made.

Most stable patients undergo chest CT for definite diagnosis. However, if diagnosis of pulmonary embolism has not been made with certainty before the patient is transported to the operating room, TEE should be performed to establish the diagnosis before the chest is opened (Kirklin/Barratt-Boyes Cardiac Surgery: Expert Consult).

In Groups 2 and 3 patients, maintaining adequate oxygenation and cardiac output is of paramount importance. This can be achieved either by endotracheal intubation and external (automatic) chest compression devices or, if available, emergent connection to an extracorporeal membrane oxygenator (ECMO) might be considered. ECMO has proven itself as an excellent tool for stabilizing such patients until their transfer to the operating room. In some instances, ECMO can stabilize patients before a definite diagnosis of massive pulmonary embolism is made, thus allow the performance of CT or echocardiography on ECMO before the final decision to perform surgical embolectomy is made.

Transesophageal echocardiogram is essential in all patients before median sternotomy is undertaken.

10.2 Surgery

A midline sternotomy is performed. If peripheral cannulation has not been established, central cannulation is undertaken, either using a single two-stage venous cannula or by bi-caval cannulation and an aortic cannula. CPB is established and mild hypothermia is instituted. Following, the surgery itself may be performed either on a beating heart or with aortic cross-clamping and cardioplegic infusion or fibrillatory arrest. Some authors advocate avoidance of aortic cross-clamping and cardioplegic arrest. (Leacche et al. 2005) Nevertheless, the literature is equivocal on the matter.

The left atrium and left ventricle may be decompressed with a venting catheter inserted into the right superior pulmonary vein.

The pulmonary trunk is incised longitudinally several centimeters distal to the pulmonary valve. If necessary, the incision can be extended into the left pulmonary artery, and a separate incision can be made in the right pulmonary artery between the superior vena cava and ascending aorta. (Fig. 5) Because of the size and fragile nature of a fresh clot in the main pulmonary arteries, it is extremely important to be able to extract the clot as much as possible without disrupting it. Therefore, in our experience, performing the operation with aortic cross-clamping, ensuring a blood-less surgical field, is the most efficient and safe way for effectively removing the clots. Additionally, various techniques and tools have been utilized for manual extraction of the pulmonary clots. It is essential to use an instrument that allows a wide and gentle grip on the clot. A sponge holder (Fig. 5, 6) or any other surgical tool that provides a wide, firm but gentle grip will assist in pulling the fresh clot without disrupting it (Fig. 7).

Fig. 5

Typical incisions and retrieval of pulmonary embolus from the left main pulmonary artery

Fig. 6

Curved sponge holder

Fig. 7

Straight sponge holder

After the main clots are removed, further attempts are made for the removal of the smaller and more distal clots. These can be extracted using Fogarty catheters, forceps and suction tube.

If a sterile pediatric bronchoscope is available, the surgeon can use this instrument to locate and remove thrombi in tertiary and quaternary pulmonary vessels. Alternatively, the pleural spaces are entered, and each lung is gently compressed to dislodge small clots into larger vessels and suctioned out.

Depending on preoperative information with regard to thrombi in the right-heart chambers, the right atrial and RV cavities are explored through a right atriotomy to search for and remove residual thrombi.

After removing the thrombus, incisions in the pulmonary arteries are closed with continuous 4–0 polypropylene suture. After completion of rewarming and evacuation of air from the cardiac chambers, CPB is discontinued. Weaning from bypass may be long, depending on the extent and how long the right ventricular was compromised before the operation. Patients after CPR and patients with a modest amount of clot removal are prone to have difficulties in weaning from the heart-lung machine (Kronik et al. 1989).

10.3 Postoperative Management

Postoperative circulatory support is often required, depending on the status of the right ventricle and whether or not it suffered any ischemia. Circulatory support can be achieved with an RV assist device and intra-aortic balloon counter-pulsation or extracorporeal life support, as indicated for patients with persisting severe RV failure at the end of surgical embolectomy. (Lango et al. 2008; Maggio et al. 2007) For patients with substantial distal blood clots in the peripheral pulmonary arteries and persistent hypoxia, ECMO may be the perfect bridge to recovery for a few days while the fresh clots undergo lysis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree