TREATMENT

Part of “CHAPTER 43 – ENDOCRINE OPHTHALMOPATHY“

Treatment of the eye changes of Graves disease is primarily palliative. The patient should be reassured that the ophthalmopathy is usually self-limited. Above all, if thyroid dysfunction is present, the patient must be rapidly treated and maintained in a euthyroid state. Subsequent hypothyroidism should be avoided (see Chap. 45). Initially, during the acute phase of the disease, elevation of the head of the bed and diuretic use may reduce the periorbital edema. A controversy has existed for some time regarding whether any of the three treatments for Graves disease (antithyroid drugs, radioiodine therapy, or thyroidectomy) was associated with greater benefit in preventing

onset or exacerbation of ophthalmopathy.13,27,28,29,30,31 and 32,53 Most of these earlier studies were poorly controlled. Three randomized clinical trials have suggested that ophthalmopathy may be more common after treatment with radioactive iodine than after medical or surgical treatment.29,39,41

onset or exacerbation of ophthalmopathy.13,27,28,29,30,31 and 32,53 Most of these earlier studies were poorly controlled. Three randomized clinical trials have suggested that ophthalmopathy may be more common after treatment with radioactive iodine than after medical or surgical treatment.29,39,41

A clear understanding by the patient that a protracted period of therapy is necessary helps to foster a good patient-doctor relationship. Encouragement that the therapy usually prevents loss of vision and maintains function is helpful for the patient’s peace of mind. Many patients are concerned about cosmetic disfigurement caused by the disease. Reassurance that this also can be managed to a considerable degree builds confidence.

Treatment of the ophthalmopathy is indicated for functional and cosmetic reasons, which frequently overlap.54 These disabilities relate to lid retraction, extraocular muscle myopathy, exophthalmos, protrusion of retrobulbar fat through the orbital septum, and optic nerve neuropathy.55

Functional disability may result from extraocular muscle malalignment causing diplopia, from vision loss because of corneal exposure owing to exophthalmos or lid retraction, or from optic nerve neuropathy. Also, soft-tissue involvement can cause severe discomfort. Cosmetic deficit may arise from upper eyelid retraction, eyeball malposition, exophthalmos, herniation of retrobulbar fat through the spaces of Charpey in the orbital septum, or soft-tissue involvement.

Lid retraction may cause both a cosmetic and functional problem. Drying of the eye from exposure, especially during sleep, leads to keratitis with constant redness, foreign-body sensation, and photophobia. In the early stages, eyedrops of 5% guanethidine (Ismelin), a sympatholytic agent, may relieve lid retraction. This drug has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration but is available for use in Europe. Some symptomatic relief may be obtained by increasing the humidity in the home environment, wearing sunglasses when outdoors, using artificial tears (1% methylcellulose) during the day, and applying emollients to lubricate the eyes at bedtime. If these measures fail to relieve the symptoms, or if the disfigurement is too great, one may turn to surgery. However, surgery should not be performed until the patient is stabilized in the euthyroid state.

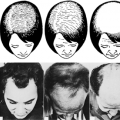

Myectomy of the Müller muscle is effective in relieving lid retraction in many cases (Fig. 43-12). The operation is not indicated, however, in cases of lid retraction secondary to tethering of the inferior rectus muscle (Collier sign) or when organic changes have occurred in the superior levator muscle. When this latter muscle becomes involved by morphologic changes, it becomes tethered so that the upper lid does not close, even under general anesthesia. A technique for testing for this is to grasp the upper eyelashes and pull inferiorly in a direction opposite the field of action of the levator muscle. When the result of this forced duction test is positive, myectomy of the Müller muscle will not alleviate the lid retraction. In this event, one must perform recession of the superior levator muscle with or without the use of some kind of donor material (preserved sclera, Tenon fascia, or preserved dura) as a spacer between the tarsus and muscle. In rare cases, the injection of a soluble corticosteroid (triamcinolone) adjacent to the levator, under ultrasonographic control, has been successful.

FIGURE 43-12. A, Right upper lid retraction in a 42-year-old woman with Graves hyperthyroidism. B, Postoperative appearance after myectomy of Müller muscle of right upper lid. |

Tethering of the inferior rectus muscle causes not only vertical diplopia, which probably is the most common functional disability, but also malposition of the eyeball, which can be cosmetically disfiguring. Recession of the muscle and lysis of adhesions between it and the lower lid retractors often restores single binocular vision. Just as often, the lower lid sags postoperatively, which necessitates another operation to elevate the lower lid to prevent exposure of the lower one-third of the globe.

Tethering of the medial rectus is not as common as inferior rectus tethering but is equally disabling. It simulates lateral rectus muscle palsy and causes horizontal diplopia and cosmetic disfigurement by eyeball malalignment (see Fig. 43-6). Surgical recession of the medial rectus muscles restores single binocular vision and corrects the disfigurement.

Progressive soft-tissue involvement may cause marked functional and cosmetic deficits. These patients may be discomforted by pain, epiphora, and photophobia, becoming functionally disabled, although no vision loss may occur. They may be markedly

disfigured, with exophthalmos, lid edema, chemosis edema of the caruncle, and conjunctival injection (see Fig. 43-1B). Ultimately, compressive neuropathy of the optic nerve at the orbital apex resulting from the enlarged extraocular muscles may ensue, and blindness becomes a distinct danger.

disfigured, with exophthalmos, lid edema, chemosis edema of the caruncle, and conjunctival injection (see Fig. 43-1B). Ultimately, compressive neuropathy of the optic nerve at the orbital apex resulting from the enlarged extraocular muscles may ensue, and blindness becomes a distinct danger.

Therapeutic options for progressive ophthalmopathy include (a) corticosteroid therapy, (b) supervoltage orbital radiotherapy, (c) surgical decompression of the orbit, and (d) combinations of these methods.

IMMUNOMODULATORY THERAPY

CORTICOSTEROIDS

A large number of immunomodulatory agents have been used in the treatment of Graves ophthalmopathy, but no single agent seems to have a clear advantage over corticosteroids.56 Corticosteroid use may produce dramatic relief of the signs and symptoms of progressive inflammatory changes. The dosage is tailored to the severity of involvement and may range from 40 to 120 mg per day of prednisone, which then is gradually tapered as improvement occurs.

When the optic nerve becomes involved, larger doses of corticosteroids are needed to restore function and save vision. The patient may need to be hospitalized if large doses of prednisone are administered (e.g., 120–140 mg per day). If adverse reactions occur, the dosage sometimes must be reduced and the treatment augmented with subtenon or retrobulbar injections of triamcinolone or methylprednisolone. As soon as the vision is restored (usually after 7 to 10 days of this therapy), the prednisone dosage is reduced. Sometimes, exacerbations occur when the dose level reaches 40 mg per day. In this event, larger doses once again must be administered. Pulse methylprednisolone treatment has been reported to be effective, with documented clinical improvement and reduced muscle size on CT scan.13 A prospective study indicates that corticosteroids may prevent worsening of ophthalmopathy in patients treated with radioiodine, but this remains controversial.39,41

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree