Figure 196.1 Massive scrotal swelling in lymphatic filariasis.

Persons new to endemic areas who acquire lymphatic filariasis usually develop acute lymphatic inflammation with lymphangitis, lymphadenitis, and, in the case of W. bancrofti, genital pain, but they may also develop allergic phenomena such as hives, urticaria, and eosinophilia.

Lymphatic filariasis is suspected from epidemiologic history, physical findings, and laboratory tests. However, a definitive diagnosis can be made only by detecting the parasite. Adult worms in lymphatics are generally inaccessible and excisional biopsies are unhelpful; however, ultrasonographic examination of the scrotum or breast in females using a high-frequency (7.5–10 MHz) transducer with Doppler may demonstrate motile adult worms within dilated lymphatics (the so-called “filarial dance sign”). Additional supportive data can be obtained with the use of lymphoscintigraphy, which (in early infections) will demonstrate a paradoxically brisk lymphatic flow on the affected side.

Microfilariae can be detected in blood and occasionally in other body fluids. Detection of microfilariae in the blood is most efficiently performed by filtering 1 mL or more of blood through a polycarbonate filter with 3-µm pores or examining the sediment from a Knott’s prep (1 mL of blood with 10 mL of 2% formalin). The timing of blood collection is critical and should be based on the periodicity of the microfilariae in the endemic region in question. Filtration of blood for nocturnally periodic microfilariae should be performed between 10 p.m. and 4 a.m. A 10- to 14-day period is required for microfilarial periodicity to adjust to local time zones.

Assays that detect circulating antigens of W. bancrofti (but not Brugia spp.) are commercially available and permit the diagnosis of filariasis in patients without microfilaremia. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assays that detect DNA of W. bancrofti and B. malayi have been developed but are not commercially available.

Data supporting filarial infection include eosinophilia, elevated serum IgE levels, and antifilarial antibodies in the serum. Serologic studies have greater diagnostic value in persons new to endemic areas. A negative or low antibody level effectively rules out active infection in this population. However, interpretation of serologic findings may be problematic because of cross-reactivity between filarial antigens and antigens of other helminths, such as Strongyloides stercoralis. In addition, residents of endemic areas may develop antibodies to filiarial antigens through the bites of infected mosquitoes without developing patent infection.

Therapy

The mainstay of treatment remains diethylcarbamazine (DEC) 6 to 8 mg/kg/day in single or divided doses for 12 days. DEC, an orphan drug, can be obtained from the CDC drug service (telephone 404–639–3670). Although extended treatment is usually necessary to kill the adults, a single dose rapidly kills microfilariae. The severity of adverse reactions correlates with the pretreatment level of microfilaremia, but the etiology is unclear and may represent either an acute hypersensitivity reaction to massive antigen release or an inflammatory reaction induced by the release of Wolbachia. Usually the reactions, which include fevers, headache, lethargy, arthralgias, and myalgias, can be easily managed with antipyretics and analgesics. Initiating treatment with a small dose of DEC (e.g., a single 50 mg tablet) and premedicating the patient with corticosteroids, 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day, minimizes side effects.

Albendazole (400 mg PO BID × 21 days) is also effective against adult worms. Doxycycline (100 mg PO BID × 4–8 weeks) targets the intracellular Wolbachia and also demonstrates effective macrofilaricidal activity. Additional treatment regimens shown to be effective include DEC and albendazole for 7 days or DEC and doxycycline for 21 days.

A note of caution: the geographic distribution of loiasis overlaps with lymphatic filariasis and coinfection occurs. Since treatment of loiasis with both DEC and ivermectin can result in severe adverse effects (see below), it is imperative to exclude the possibility of coinfection with loiasis prior to treating patients with lymphatic filariasis.

Because adult worms may survive the initial treatment, symptoms can recur within a few months after therapy, and retreatment is recommended for such patients. Some individuals have suggested treating such patients with DEC at the standard dose of 6 to 8 mg/kg/day for 1 week each month for 6 to 12 months. Combination therapy with DEC and either albendazole or ivermectin (sometimes preceded by doxycycline) has demonstrated efficacy for mass chemotherapy of filariasis.

The optimal treatment of acute lymphatic inflammation is unknown, and these attacks usually resolve in 5 to 7 days without therapy. Treatment of chronic lymphatic obstruction is problematic. If the infection is recognized early, some signs of lymphatic obstruction can be reversed. In severely damaged lymphatics, however, supportive measures are used, including elevation of the infected limb, elastic stockings, and foot care with antifungal ointments and antibacterial antiseptics. Prophylactic antibiotics may prevent recurrent bacteremia and cellulitis. Hydroceles can be managed surgically, and surgical decompression with a nodovenous shunt may provide relief for severely affected limbs. No treatment has proved satisfactory for chyluria. DEC is useful for prophylaxis, but the optimal dose and frequency have not been established.

Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia

Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia (TPE) is a distinct syndrome caused by immunologic hyperresponsiveness to W. bancrofti or B. malayi. The syndrome affects men four times as commonly as women, often in the third decade of life. Most cases have been reported from Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, and Brazil.

The symptoms and signs of TPE are attributed to trapping of microfilariae in pulmonary vasculature, with resultant eosinophilic alveolitis; patients develop paroxysmal cough and wheezing that is nocturnal and due to the nocturnal periodicity of the microfilariae, anorexia, and low-grade fever. Extreme eosinophilia (>3000/mm3), high polyclonal IgE levels, elevations of antifilarial antibodies, and a therapeutic response to DEC establish the diagnosis.

Therapy

DEC is recommended at 4 to 6 mg/kg/day for 14 days. Symptoms usually resolve within 1 week. Most patients are already being treated with corticosteroids, which can be tapered as patients recover. Up to 25% of treated patients relapse, requiring retreatment.

Loiasis

Also known as African eyeworm, loiasis results from infection with Loa loa acquired in the rain forests of West and Central Africa. After the bite of an infected tabanid (horse) fly, the parasites are inoculated into the subcutaneous tissue, where they mature and mate. The adults reside in subcutaneous tissue and migrate widely over the body. The microfilariae released into the blood by the adult female exhibit diurnal periodicity. These parasites do not contain Wolbachia.

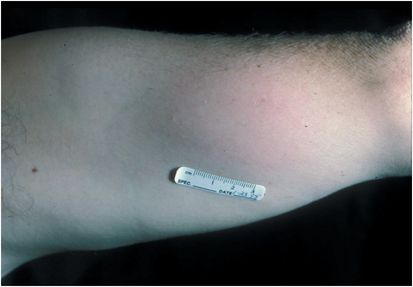

Clinical manifestations differ between natives to endemic areas and newcomers. In the indigenous population, microfilaremia is generally asymptomatic, remaining subclinical until the adult migrates through the subconjunctival tissues of the eye or causes Calabar swellings, which are angioedematous lesions in the extremities (Figure 196.2). The swelling develops after the adult has migrated through the tissue, so biopsy is fruitless. Nephropathy, encephalopathy, and cardiomyopathy are rare. In nonresidents, allergic or hypersensitivity responses predominate and microfilaremia is rare, but Calabar swellings occur more frequently and are more debilitating. Peripheral blood eosinophilia, parasite-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG), and vigorous lymphocyte proliferation to parasite antigens are typical.

Figure 196.2 Calabar swelling of loiasis.

Definitive diagnosis requires either identification of microfilariae in peripheral blood or isolation of the adult worm. The microfilariae can be identified with the technique described for lymphatic filariasis. However, because the microfilariae of Loa loa exhibit diurnal periodicity, blood must be filtered between noon and 4 p.m. after the patient has been in the local time zone for 10 to 14 days. The adult worm is difficult to find unless it crawls across the eye. The worm is not found in Calabar swellings, and biopsy of these lesions is not indicated. In amicrofilaremic patients the diagnosis must be based on a characteristic history and clinical presentation, blood eosinophilia, and elevated levels of antifilarial antibodies.

Therapy

The drug of choice to treat loiasis is DEC, which is effective against both the adult worm and microfilariae. It is dosed as 8 to 10 mg/kg/day (divided into three doses) for 21 days. A single course of therapy is curative in the majority of patients, although multiple courses may be required, and clinical relapses may occur up to 8 years following apparently successful treatment. It is not unusual for treated patients to develop localized inflammatory reactions such as subcutaneous papules or vermiform hives. These reactions, which are distinct from Calabar swellings, are a response to dying adult worms. The adult worms can be surgically extracted from these lesions, but removal is usually unnecessary.

Greater caution is warranted in patients who have microfilaremia. Treatment of such individuals with standard dosages of DEC has resulted in severe neurologic complications and even death caused by microfilariae in the central nervous system (CNS). In order to reduce the risk of developing treatment-induced encephalopathy, some experts have tried to reduce the microfilarial burden by performing apheresis of the blood before initiating treatment with DEC. In addition, gradual institution and escalation of DEC doses has been successful. DEC is gradually instituted, giving 0.5 mg/kg for the first dose then doubling every 8 hours until the full dose of 8 to 10 mg/kg/day (divided into three doses) is achieved. Prednisone (1 mg/kg/day) should be used during the first 3 to 6 days of treatment, and the first dose of prednisone should be given at least 6 hours before the first dose of DEC.

Since onchocerciasis occurs in the same geographic areas as loiasis and treatment of onchocerciasis with DEC can result in severe adverse effects, the clinician must rule out coinfection with onchocerciasis.

Other side effects of treatment are pruritus, fever, anorexia, lightheadedness, and hypertension. These symptoms usually resolve after the first few doses. A single course of DEC cures roughly half of those treated, and additional courses are frequently necessary to achieve cure. The decision to repeat treatment must be made on clinical grounds, since no objective laboratory data can predict treatment failures. Albendazole is an attractive treatment option for patients with high levels of microfilaremia: 200 mg twice daily for 3 weeks results in a gradual decline in microfilaremia over several months.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree