Thrombohemorrhagic Events in the Elderly: Special Considerations

Isabelle Mahe

Ludovic Drouet

Our society is gradually aging, and in view of the increased incidence of thrombotic conditions associated with the elderly, knowledge of anticoagulation drugs and how to use them in older patients has become essential. The treatment of elderly patients is complex, since older patients are at increased risk for both thrombosis and bleeding.

AGE: A RISK FACTOR FOR THROMBOSIS

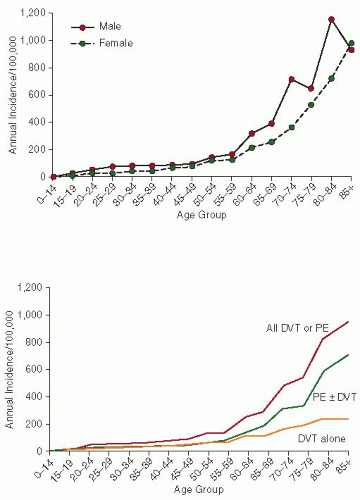

It has been widely demonstrated that the incidence of thromboembolic diseases increases sharply after the age of 651, 2, 3, 4: venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), but also atrial fibrillation (AF) and associated risk of cardioembolic stroke. Elderly patients are therefore the main target population for anticoagulation therapy. In the general population, VTE disease has an incidence of 1 to 2 per 1,000 individuals per year, but this incidence is almost 1% perannum in patients aged over 701, 2 (FIGURE 130.1). Overall 70% of patients with VTE are over 60 years of age.3 Age is also an independent risk factor for death in patients with PE.4 The mortality due to PE during hospital stay is 21% in patients older than 65 years and may be as low as 2% in patients younger than 40 years.

DVT is a common age-related condition in medical inpatients: in a prospective study, the prevalence of asymptomatic DVT within 48 hours after admission was 17.8% in patients over 80 years and 0% in patients under 55 years.5 While the reasons for this high incidence of VTE have not yet been fully elucidated,6 it has been suggested that the causes are multiple, a combination of (a) malignancy (attributable risk of malignancy is close to 35% in this subset, compared to 20% in the general population with VTE), (b) acquired prothrombotic conditions that are much more common in the elderly (population attributable risk for comorbidities of 25%), and (c) the ageing vascular system with the prothrombotic/antithrombotic systems tilting toward the former in the elderly. The benefit-to-risk ratio of antithrombotic therapy may be difficult to assess in the elderly since they are at the highest risk of severe VTE but also of bleeding events while on anticoagulants. That was observed in the RIETE registry comparing patients older and those under 80 years treated for VTE events: 50% of all patients with fatal PE and 36% of those with fatal bleeding were >80 years old.7 In those patients, the 3.7% incidence of fatal PE outweighed the 0.8% of fatal bleeding, supporting the favorable benefit-to-risk ratio of anticoagulants in elderly patients with VTE. Haspel et al.8 tried to model the expected effect of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) treatment in patients older than 80 as compared with patients 60 years of age, taking into account age-appropriate thromboembolic recurrence rates after PE, major bleeding risks of warfarin use, and the contribution of falls to major bleeding episodes in anticoagulated elderly patients. Extended anticoagulant therapy for idiopathic PE is still favorable in elderly patients who tolerate the initial 6 to 12 months of therapy without bleeding complications, irrespective of fall risk.

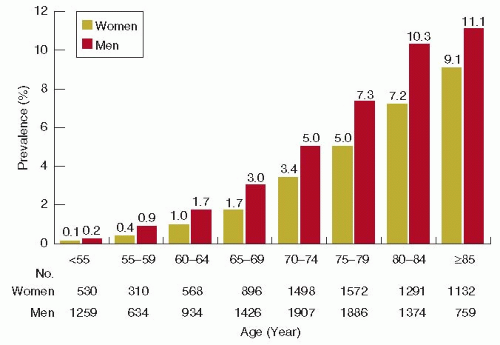

AF affects 1% to 2% of the population. The prevalence rises dramatically with age, reaching 5% to 15% at the age of 809, 10 (FIGURE 130.2). The lifetime risk of developing AF is 25% in patients who have reached the age of 40.11 In addition, aging is an independent major risk factor for ischemic embolic stroke; patients aged 75 years or older have a significant thromboembolic and therefore stroke risk, even if they have no other embolic risk factors.12, 13, 14 Patients over 75 years of age have an individual yearly risk of thromboembolism of 4%.14 In the recent recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology, age was considered a major risk factor for embolic events, as was a history of cardioembolic events, accounting for 2 points in the calculation of the CHA2DS2-VASc score. In addition, age over 75 is associated with a worse prognosis for stroke and mortality than hypertension or diabetes.

With increasing age, the efficacy of VKA for the prevention of arterial embolic events in AF patients does not decrease whilst antiplatelet therapies lose their efficacy, becoming negligible by the age of 77.15, 16 In view of the higher incidence of cardioembolism in elderly patients, VKA treatment is at the present time, almost the only effective prophylactic agent in this population.17, 18 As the population ages, the number of elderly patients who require warfarin therapy is rising steadily, owing to an increase in the prevalence of AF and VTE, the main indications for anticoagulant therapy.

AGE: A RISK FACTOR FOR BLEEDING

Anticoagulants and Risk of Bleeding in Elderly Patients

A large number of studies performed with various anticoagulants (e.g., unfractionated heparin [UFH] and low molecular weight heparins [LMWHs], or VKA) have concluded that the risk of bleeding is higher in elderly patients.19, 20 Intracerebral bleeding is the most serious and feared complication of VKA treatment. Aging is a major independent risk factor for intracerebral hemorrhage, especially in patients aged over 85: the relative risk for intracranial bleeding in patients over 75 is 3.7 as compared to patients aged <75. The relative risk for major bleeding is 4.5 in patients over 80 versus those younger than 80.21, 22, 23, 24, 25

Aspirin is often intuitively preferred to warfarin in elderly patients because of the risk and the fear of bleeding. There are several arguments against this strategy: first, VKA is the only

effective drug in elderly patients, and second, the risk of major bleeding with aspirin in elderly patients approaches the risk associated with warfarin, as shown in the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged study (2.0% per year in both groups).25 One of the main advantages of therapeutic doses of LMWH over UFH is the lower risk of major bleeding events (1.2% vs. 2%; odds ratio [OR] 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.39 to 0.83).26 Elderly patients, however, are frequently renally impaired. A French Drug Agency survey showed that independent risk factors for hemorrhage in patients treated with LMWH are: age over 75, renal impairment, and prolonged duration of treatment.27 Conversely, in the Innohep in Renal Insufficiency Study (IRIS)28 comparing UFH and the LMWH, tinzaparin at therapeutic doses followed by VKA treatment in patients older than 70 years presenting with DVT (mean age 82.6 years), found no difference in the risk of clinically relevant bleeding at 3 months (11.9% in both arms, P = 0.97). In this trial, 25% of the population had severe renal impairment.28

effective drug in elderly patients, and second, the risk of major bleeding with aspirin in elderly patients approaches the risk associated with warfarin, as shown in the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged study (2.0% per year in both groups).25 One of the main advantages of therapeutic doses of LMWH over UFH is the lower risk of major bleeding events (1.2% vs. 2%; odds ratio [OR] 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.39 to 0.83).26 Elderly patients, however, are frequently renally impaired. A French Drug Agency survey showed that independent risk factors for hemorrhage in patients treated with LMWH are: age over 75, renal impairment, and prolonged duration of treatment.27 Conversely, in the Innohep in Renal Insufficiency Study (IRIS)28 comparing UFH and the LMWH, tinzaparin at therapeutic doses followed by VKA treatment in patients older than 70 years presenting with DVT (mean age 82.6 years), found no difference in the risk of clinically relevant bleeding at 3 months (11.9% in both arms, P = 0.97). In this trial, 25% of the population had severe renal impairment.28

The risk of major bleeding with new anticoagulants is also higher in elderly patients. Dabigatran is the first drug demonstrating a significant reduction of intracranial—including intracerebral—bleedings in the whole population with AF and also in elderly patients. However, this reduction in the risk of intracranial bleeding is counterbalanced by an increase in major gastrointestinal bleedings, the mechanism for which remains unknown.29, 30

Risk Factors for Bleeding in Elderly Patients

The general risk factors for bleeding in association with anticoagulant therapy are described in Chapter 107. This chapter deals with the aspects specifically related to the elderly. The risk of bleeding depends on both patient- and treatment-related factors (Table 130.1). The incidence of major bleeding events also depends on the duration of anticoagulant treatment; it is

highest at the beginning of treatment, drops to 3% during the 1st month of anticoagulation, to 0.8% per month during the 1st year, and 0.3% per month thereafter.24 In a recent inception cohort study, Hylek et al.31 reported a reliable high risk (7.2%) of major bleeding during the 1st year following VKA initiation in patients ≥65 years of age with AF, with 4.7% for those <80 years, and 13.1% for those ≥80 years.

highest at the beginning of treatment, drops to 3% during the 1st month of anticoagulation, to 0.8% per month during the 1st year, and 0.3% per month thereafter.24 In a recent inception cohort study, Hylek et al.31 reported a reliable high risk (7.2%) of major bleeding during the 1st year following VKA initiation in patients ≥65 years of age with AF, with 4.7% for those <80 years, and 13.1% for those ≥80 years.

Table 130.1 Risk factors for bleeding in elderly patients receiving VKAs | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

Factors Related to Treatment

VKA Treatment

The risk of major bleeding increases exponentially with international normalized ratio (INR) over 4 compared to an acceptably low incidence at INR between 2 and 3; it should be noted that the risk of intracranial bleeding is not significantly lower at treatment intensities <2.0.22 Excessive dosing of VKA is common in geriatric patients: two observational studies reported an incidence of 25% among patients (aged over 80) with at least one INR result higher than five while it was <15% in patients <60 years, P = 0.003.32, 33

INR Variability

Extreme INR values (both very low and very high) are more common in the elderly than in young patients, resulting in frequent measurements and dose adjustments.32 The elderly are more prone to instability due to an increasing number of comorbidities as well as of drugs that interact with warfarin. There is a 21% fall over a 15-year period in the dose of VKA needed in the elderly to reach the same INR target.34 This increase in sensitivity with age appears to be independent of other demographic factors.35 Consequently, elderly patients are more sensitive to even very moderate dose adjustments. Low-dosage-VKA formulations (warfarin) are therefore recommended.36

Patient-related Factors

Comorbidities

Elderly patients have a higher risk of bleeding owing to an accumulation of comorbidities and polypharmacy. Acute as well as chronic comorbidities and acute concomitant diseases tend to have an impact on the sensitivity to VKA. Diseases that affect the sensitivity to VKA and that are common in elderly patients are listed in Table 130.1.37, 38 Hepatic function is also altered in the elderly and any fluctuation affects the synthesis of coagulation factors, VKA metabolism, and the anticoagulant effect. Another major point, often missed in elderly patients, is the nutritional status.38, 39, 40 Dietary changes have long been recognized as a factor for instability of anticoagulation. In the elderly, dietary vitamin K intake is most often low, which contributes to their increased sensitivity to VKA.39 In a 6-month randomized placebo-controlled study, a daily vitamin K supplementation in patients with unstable anticoagulation resulted in a significant improvement in anticoagulation control versus the previous 6-month period and to a greater extent than in the placebo group.40

Another crucial modulator is hypothyroidism, which is observed in approximately 15% of elderly individuals.41 Fluctuations in thyroid function result in instability of anticoagulation. Increasing thyroid activity (hyperactivity of the thyroid gland or from exogenous thyroid hormones) is associated with a hypercoagulable state.42, 43 Hyperthyroidism may also increase the sensitivity to VKA, perhaps by boosting catabolism of vitamin K-dependent factors.39 Patients with suspected thyroid dysfunction should be carefully monitored when receiving VKA and must be made aware that any change in their thyroid function may have a knock-on effect on their anticoagulant response.

Compliance with Treatment

In elderly patients, compliance with treatment is often difficult to obtain as a result of progressive cognitive impairment. Waterman demonstrated that age over 80 is predictive for out-of-range INR, resulting from insufficient compliance.44 In practical terms, these patients should be given their pill by a caregiver.

Leukoaraiosis and Microbleeds

A recently recognized risk factor for intracerebral bleeding in elderly patients is leukoaraiosis,45 which is defined as a diffuse, confluent white matter abnormality with low density on computed tomography (CT), and hyperintensity on T2-weighted or FLAIR magnetic resonance imaging. No consensus on the precise mechanisms linking the pathology of the vessel walls with tissue injury has been reached; ischemia, blood-brain barrier dysfunction, and endothelial dysfunction have all been suggested as causative mechanisms. The Stroke Prevention In Reversible Ischemia Trial, in which patients with cerebral ischemia were randomized to warfarin (INR 3 to 4.5) or aspirin,46 was stopped before its scheduled end because of an excess risk of intracerebral bleeding. Leukoaraiosis was an independent risk factor for bleeding in this study (OR 9.2). Furthermore, in patients with a history of ischemic stroke, leukoaraiosis is a major and independent risk factor for subsequent warfarin-associated intracranial hemorrhage with an OR of 12.9 (95% CI, 2.8 to 59.8), as observed in a case-control study.47 More recently, leukoaraiosis was reported to be associated with poor prognosis

after spontaneous hemorrhage.48 In a review of the literature, O’Sullivan45 found support for a link between gait disturbance, falls, and leukoaraiosis, which is associated with an increase in the risk of fractures and hospitalization.

after spontaneous hemorrhage.48 In a review of the literature, O’Sullivan45 found support for a link between gait disturbance, falls, and leukoaraiosis, which is associated with an increase in the risk of fractures and hospitalization.

In a recent systematic review on cerebral microbleeds and the risk of cerebral hemorrhage, users of antithrombotic drugs were compared to nonusers.49 Patients with microbleeds at baseline and who were treated with antithrombotic agents had an increased risk of subsequent intracerebral hemorrhage (OR 12.1, 95% CI 3.4 to 42.5), suggesting that microbleeds may play a role in the risk of warfarin-related intracerebral bleeding.49

Drug Interactions

Elderly patients frequently take multiple concomitant medications. Polypharmacy is an independent risk factor for bleeding: Kagansky et al.50 reported an OR of 6.14 (95% CI, 1.2 to 42.4) for major bleeding in elderly patients receiving more than seven medicines versus those receiving seven or less. Nonsteroid antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and especially aspirin increase the risk of bleeding when associated with anticoagulant drugs. Many mechanisms are involved, including long duration of action, platelet function inhibition, gastric erosion and ulcerations causing gastrointestinal bleeds.19

Susceptibility to Falls

A susceptibility to falls is often the direct reason for not prescribing VKA to elderly patients. Falls are very common in this population, causing morbidity and mortality.51 Dizziness and disequilibria occur frequently and are usually the cause of falls in the elderly.52 The associated risk of bleeding is most often overstated.53 The real risk of intracranial bleeding induced by falling is so low that a patient would have to fall 300 times per year before the risk associated with VKA outweighs the benefit of stroke prevention. This type of fall must be distinguished from syncope, which causes sudden falls without any prodromal symptoms, usually related to cardiac conduction disorders.

Renal Impairment

Renal function decreases gradually with age. A substantial proportion of elderly patients (>75 years) have moderate or severe renal impairment.54 With age-related decline in renal function presents the issue of accumulation of renally eliminated antithrombotic drugs. Nevertheless, renal impairment on its own is a demonstrated risk factor for bleeding during anticoagulant treatment, affecting anyone of UFH, LMWH, and VKA19, 20, 55, 56 and even the new oral anticoagulants. It must, however, be kept in mind that this condition not only increases the risk of bleeding but also the risk for thromboembolic events and death.57, 58, 59, 60

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree