Fig. 11.1

Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) scoring system

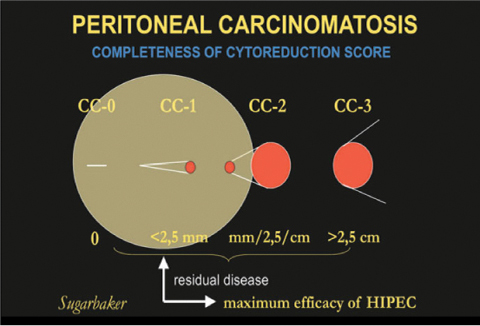

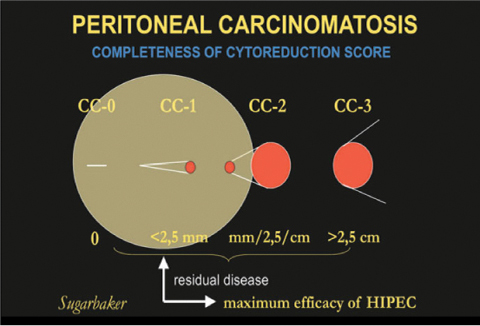

11.4 Defining Completeness of Cytoreduction: CC score

Completeness of cytoreduction is the most important prognostic factor after CRS. Residual disease after CRS is properly described using the Completeness of Cytoreduction (CC) score [12] (Fig. 11.2):

CC-0, no visible residual tumor

CC-1, residual tumor nodules < 2.5 mm

CC-2, residual tumor nodules between 2.5 mm and 2.5 cm

CC-3, residual tumor > 2.5 cm

Fig. 11.2

Completeness of Cytoreduction (CC) scoring system. HIPEC, hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. (Modified from [12])

Adequate cytoreduction is defined as CC-0 or 1 because only microscopic or minimal residual nodules are targeted by IP-administered drugs; IP-CHT is not indicated if a CC-2 or 3 score is obtained after CRS. The probability of adequate cytoreduction is correlated with the extent of PC, as described by the PCI.

11.5 How can Surgery Achieve Complete Cytoreduction? CRS, Peritonectomy, and Sugarbaker Procedures

The techniques required to accomplish complete surgical resection of PC were detailed by Sugarbaker [13, 14] and consist of six different peritonectomy procedures (aimed at resecting peritoneal surfaces that contain tumor implants) and visceral dissections, with maximal surgical effort to remove as much macroscopic tumor as possible, followed by direct instillation of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) to address microscopic residual disease (Table 11.1).

Table 11.1

Sugarbaker peritonectomy procedures

1 | Greater omentectomy, right parietal peritonectomy, right colon resection |

2 | Left upper quadrant peritonectomy, splenectomy, and left parietal peritonectomy |

3 | Right upper quadrant peritonectomy and Glissonian capsule resection |

4 | Lesser omentectomy, cholecystectomy, stripping of omental bursa, and antrectomy |

5 | Pelvic peritonectomy with sigmoid colon resection with or without hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy |

6 | Other intestinal resection and/or abdominal mass resection |

7 | Bowel anastomosis |

The need to perform one or more CRS procedures to achieve complete cytoreduction and the subsequent risk of postoperative complications is strictly related to disease extent described by PCI score. Postoperative complication and mortality rates after CRS range from 20 % to 50 % and from 2 % to 12 %, respectively, so that proper patient selection and careful evaluation of disease extent of are required prior to CRS [14]. In general, a PCI score > 20 is accepted as indicative of poor chances of obtaining adequate cytoreduction [15]. For PC from gastric cancer, some authors suggest a PCI ≤ 12 as a threshold for expecting a CC-0 surgery with minimal complication rates [11, 16]. The role of adequate surgical technique and surgeon skill in reducing complications and obtaining adequate cytoreduction is emphasized by several authors, as is the importance of the learning curve for this complex surgical procedure. With adequate experience, surgeons can achieve adequate cytoreduction with acceptable risk, even in selected patients with PCI > 20 [17].

11.6 Cytoreduction Completeness and Patient Survival

When interpreting results of the CRS plus IP-CHT strategy, the relative contribution of each CRS and IP-CHT in determining survival benefit remains unclear. Nevertheless, there is uniform agreement that cytoreduction completeness is the only variable clearly associated with increased survival rates, with optimal results being achieved when a CC-0 is accomplished [18]. Even in PC from CRC and gastric cancer, the impact of CC-0 surgery on survival benefit clearly emerged from randomized controlled trials (RCTs). In PC from CRC, an impressive 22–43 % 5-year survival rate was observed in CC-0 patients after CRS plus HIPEC [19], with those results being maintained even after a longterm follow-up [20].

Even without IP-CHT or HIPEC, an aggressive surgical strategy for obtaining a zero-residual tumor is a mainstay of therapy in patients with advanced ovarian cancer, with systemic CHT being considerably less effective in women with macroscopic residual tumor after surgery [21, 22]. In order to reduce the IP cancer load before surgery and increase chances for adequate cytoreduction, systemic neoadjuvant CHT has been proposed in ovarian and gastric cancer patients. In some centers, IP-CHT is also administered together with systemic CHT in a neoadjuvant setting for gastric PC [23]. In treating PC from gastrointestinal and ovarian cancer, CRS, IP-CHT, HIPEC, and systemic CHT become part of a multimodal treatment strategy: all cases should be discussed in a multidisciplinary team including surgeon, clinical oncologist, radiotherapist, pathologist, radiologist, and anesthesiologist in order to target therapy and select patients suitable for a CC-0 surgery with a low risk for complications and the greatest chance to benefit from this complex strategy.

11.7 Selecting Patients for CRS

There is much controversy among clinical oncologists and surgeons around this subject, many of the former being convinced that the positive results obtained with CRS and IP-CHT are mainly due to patient selection. There is no doubt, however, that in selected patients (i.e., patients with PC load amendable by surgery), CRS + IP-CHT, eventually followed by systemic CHT, provides better results than systemic CHT alone [18].

PC patients are often denied surgery and sent for multiple cycles of systemic CHT, which shows only limited effects. They are referred to the surgeon only in case of bowel obstruction or perforation and are proposed for CRS plus IP-CHT only after the failure of several cycles of systemic CHT, by which time the cancer load is massive and patients are usually physically wasted: in this setting, there is little chance of obtaining a CC-0 operation; patients often require multiple peritonectomy procedures and multiorgan resections and are at maximum risk for perioperative complications [24]. Early referral to surgery should thus be encouraged, so that the tumor load is limited, a CC-0 resection is still possible with a reduced need for multiorgan resections, and the risk for complications is minimal. In this scenario, patients recover better after surgery and are eventually fit for adjuvant systemic CHT, if indicated. On the other hand, patients with massive PC (PCI > 20) who are not suitable for optimal cytoreduction should not be treated with CRS plus IP-CHT, because they often require extensive surgical resections and experience a high risk of complications and mortality, with little chance of improving their survival and quality of life [14].

11.8 Reducing Complications after CRS

Patient selection and surgical quality are the most important factors in preventing postoperative complications [24]. Several factors are associated with risk of complications, including the number of anastomoses performed, the need for diaphragmatic resection, scald injuries to the bowel due to HIPEC, the toxicity of IP-CHT itself, and the number of blood transfusions required. In preventing complications, a skilled anesthesiologist is required for careful intraoperative patient management: during CRS plus HIPEC, patients face several dangers, such as hyperthermia, abdominal hypertension, electrolyte abnormalities, coagulopathies, increased cardiac index, reduced oxygen consumption, and decreased systemic vascular resistance [25]. In the postoperative period, anastomotic leakage, bowel obstruction due to adhesions, bowel perforation due to scald injury, or direct toxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs are the most anticipated complications. In most centers, a diverting stoma is performed when there is need for multiple anastomoses or rectal anastomosis. When complications develop, it is often difficult to differentiate between morbidity resulting from surgery and that attributable to IP-CHT or HIPEC: in order to optimize the reporting of postoperative complications, the NCI-CTCAE classification should be adopted [24, 26].

11.9 Learning Curve

Recent reports suggest that the initial high morbidity and mortality rates seen with CRS and HIPEC decreases with increasing surgeon experience [27–29]. This is evident in specialized centers and includes improvements in patient selection, surgical expertise and postoperative management. This increased information base is culminating in a global learning curve and reduced complications rates (Table 11.2).

Table 11.2

Mortality according to increasing experience using cytoreduction and HIPEC for peritoneal carcitomatosis

% Perioperative Mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Study [Reference] | Initial | Intermediate

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |