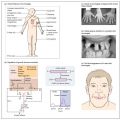

A 51-year-old man was referred to the Endocrine Clinic as an emergency complaining of loss of vision in both sides of his visual field. He had been increasingly tired over the preceding few months, felt ‘sluggish’ and had lost all motivation for his usual activities. He was shaving less frequently than normal and had lost some body hair. He had also lost interest in sex, although put this down to his exhaustion and ‘getting older’. More recently, he felt dizzy when he got out of bed or stood up from a chair. On examination he had clinical features of pan- hypopituitarism and examination of his visual fields revealed a bitemporal hemianopia. Biochemical investigations confirmed the presence of hyperprolactinaemia (serum prolactin 35 000 mU/L) and suppressed values of cortisol, thyroxine, TSH, LH, FSH, testosterone and IGF-1. An MRI scan showed a large pituitary tumour extending superiorly from the pituitary fossa and compressing the optic chiasm. He was treated with cabergoline, a long-acting dopamine agonist drug which subsequently caused shrinkage of the tumour. Examples of pituitary tumours are shown in Fig. 5a.

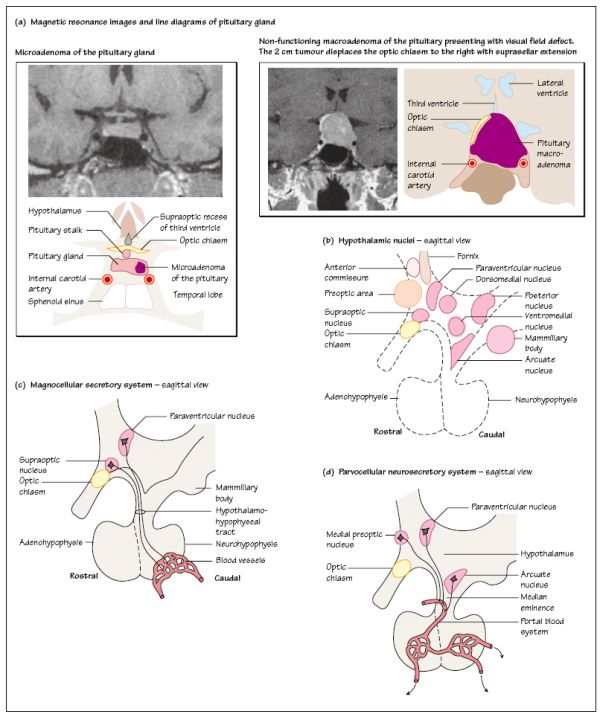

The hypothalamus lies at the base of the brain in the diencephalon. It contains a number of nuclei of neurones important in the regulation of hormone secretion from the pituitary. Some of these neurones produce hormones which are transported in the bloodstream to the pituitary. The hypothalamic boundaries are arbitrarily defined, in terms of visible structures around it, into the: rostral or supraoptic hypothalamus; middle or tuberal hypothalamus; and caudal or mamillary hypothalamus (Fig. 5b). Running longitudinally through the middle is the narrow third ventricle.

The medial hypothalamus contains a number of nuclei (Fig. 5b), densely packed with cells, which communicate with the rest of the brain through a bundle of descending and ascending axons: the medial forebrain bundle.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree