Patient

Young age

White race

Private insurance

Family history of breast cancer

Tumor

Infiltrating lobular histology

Multicentric disease

Tumor size

Treatment

BRCA testing

MRI

Breast reconstruction

Facility type

Reasons for Increased CPM Rates

This trend towards more aggressive breast cancer surgery is curious and appears somewhat counterintuitive in the modern era of minimally invasive surgery. The following section of this chapter is largely speculative because the exact reasons for increased CPM rates in the United States are really unknown. However, many factors are likely to contribute to the increased use of CPM. Public awareness of genetic breast cancer and increased BRCA testing may partially explain these observations. Improvements in mastectomy (including skin-sparing and nipple-sparing mastectomy) and reconstruction techniques and access to plastic surgeons who specialize in breast reconstruction probably contribute to increased CPM rates. Moreover, symmetric reconstruction is often easier to achieve after bilateral mastectomy as compared to unilateral mastectomy. Additionally, the native and reconstructed breast age differently, so symmetric outcomes may diminish over time.

Several studies have reported that preoperative breast MRI is associated with higher CPM rates [18, 20]. The proposed explanation is that MRI findings introduce concern about the opposite breast. For example, a patient is diagnosed with a unilateral breast cancer, and clinical breast examination and mammography of the contralateral breast are normal. The patient is an ideal candidate for breast-conserving treatment. However, an MRI is obtained which demonstrates an occult indeterminate lesion in the contralateral breast. Next, the patient undergoes a second-look (targeted) ultrasound to characterize this MRI finding. The ultrasound imaging is normal, so she gets called back again for an MRI-guided biopsy, which is negative for cancer. However, the patient decides to have bilateral mastectomy to avoid this stressful scenario again. Preoperative breast MRI probably contributes to increased CPM rates, but the initial observed CPM trends in the United States preceded the widespread use of breast MRI [15, 17].

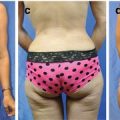

Obesity rates in the United States have markedly increased over the past two decades. An obese woman with large breasts may encounter symmetry and balance problems after unilateral mastectomy without reconstruction. Additionally, the plastic surgeon may have technical challenges in achieving a symmetric reconstruction after unilateral mastectomy for an obese woman with large, pendulous breasts. For some women, bilateral mastectomy with or without reconstruction may provide effective local breast cancer treatment, avoid future radiographic surveillance, and may relieve the chronic symptoms often associated with macromastia. Nevertheless, it is not known with certainty whether increasing obesity rates in the United States are contributing to current CPM trends.

Another possible explanation for the increased CPM rates is that some patients may considerably overestimate their risk of contralateral breast cancer. Previous studies have reported that women with early breast cancer markedly overestimate their risk of recurrence [26]. In a recent survey of 350 mastectomy patients, Han et al. reported that the most common reason for CPM was worry about contralateral breast cancer [27]. However, the rates of metachronous contralateral breast cancer have declined in the United States in recent decades [28]. The increased use of adjuvant therapies likely explains these findings.

The Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group recently updated their meta-analyses and reported that the annual rate of contralateral breast cancer was about 0.4 % for patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer treated with tamoxifen [29]. The annual rate of contralateral breast cancer was about 0.5 % for patients with estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Thus, the 10-year cumulative risk of contralateral breast cancer is about 4–5 %. Abbott et al. recently published the results of a prospective single-center study designed to determine a patients perceived risk of contralateral breast cancer [30]. Patients completed a standardized survey prior to surgical consultation and were asked to estimate their risk of contralateral breast cancer. Patients substantially overestimated their 10-year cumulative risk of contralateral breast cancer, with a mean perceived risk of 31.4 %.

Moreover, some patients may overestimate the oncologic benefits of CPM. In a review of open-ended comments from women who underwent CPM, Altschuler et al. recorded comments such as “I do not worry about recurrence” and I am “free of worries about breast cancer” [12]. Such comments suggest a true lack of understanding as to the benefits of CPM, since removal of the normal contralateral breast does not treat systemic metastases from the known ipsilateral breast cancer.

Outcomes After CPM

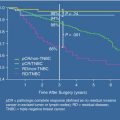

Several studies have demonstrated that CPM is effective in reducing the risk of contralateral breast cancer. In a study of 745 breast cancer patients with a family history of breast cancer, McDonnell et al. reported that CPM reduced the incidence of contralateral breast cancer by more than 90 % [31]. In a retrospective study of 239 patients, Goldflam et al. reported that only one contralateral breast cancer (0.4 %) developed after CPM [8]. Depending upon the statistical methods used, CPM reduces the risk of contralateral breast cancer by about 90 %.

However, the effectiveness of CPM in reducing breast cancer mortality is not as clear. The only plausible way that CPM improves breast cancer survival is by reducing the risk of a potentially fatal contralateral breast cancer. A recent survival analysis of the SEER database included patients with unilateral breast cancer diagnosed between 1998 and 2003 [32]. The authors concluded that CPM is associated with a small improvement (4.8 %) in 5-year breast-cancer-specific survival rates for young women with early-stage estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer.

Of note, the cumulative incidence of contralateral breast cancer was less than 1 % in this study; therefore, the apparent survival benefit is most likely due to selection bias. In a retrospective single-center study, Boughey et al. reported that CPM was associated with improved overall survival and disease free survival rates [33]. However, a recent Cochrane review of published CPM studies concluded that there is insufficient evidence at the present time that CPM improves overall survival [7].

Despite the results of retrospective or cancer registry studies, CPM is not likely to improve breast cancer survival rates for patients who do not have BRCA mutations. For these patients, the 10-year cumulative risk of contralateral breast cancer is about 4–5 %; most metachronous contralateral breast cancers are stage I or IIA with a 10-year mortality rate of about 10–20 %. Thus, the 20-year mortality rate from a contralateral breast cancer is about 1 % or less. In addition, many patients die from systemic metastases from their known ipsilateral breast cancer or from other causes during 20-year follow-up. Finally, CPM does not prevent all contralateral breast cancers. Thus, CPM will likely not decrease breast cancer mortality rates for most breast cancer patients without BRCA mutations.

On the other hand, for patients with BRCA-associated unilateral breast cancer, the annual risk of contralateral breast cancer is about 4 % per year with a cumulative 10-year risk of contralateral breast cancer of about 40 % [34]. Thus, the possibility of developing a potentially fatal contralateral breast cancer is substantially higher among breast cancer patients with a BRCA mutation. The relative risk reduction of CPM is similar for patients with and without BRCA mutations. Using Markov modeling, Schrag et al. estimated that CPM would increase life expectancy by 0.6–2.1 years for a 30-year-old patient with a BRCA mutation [35]. Clearly, randomized trials comparing CPM versus no CPM for either selected (BRCA mutations) or heterogenous patients are not feasible.

Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy is an irreversible procedure and is not without risks. Some of the more severe potential complications after CPM may significantly delay recommended adjuvant therapy, such as chemotherapy. Complications that require additional surgical procedures and subsequent loss of reconstruction must be considered and thoroughly discussed with all patients. The overall complication rate after bilateral mastectomy and reconstruction is about 20 % [8]. About half of the complications are secondary to the prophylactic mastectomy. Even without complications, these operations are relatively lengthy (often 5–6 h) and require 2–3 days of inpatient hospital care, drainage catheters, and about 3–4 weeks of overall recovery.

Despite potential risks and complications, most patients are satisfied with their decision to undergo CPM. The greatest reported benefit contributing to patient satisfaction is a reduction in breast cancer-related concerns. Frost et al. reported that 83 % of patients were either satisfied or very satisfied with their decision to undergo CPM at a mean of 10 years after surgery [36]. Some women have negative psychosocial outcomes following CPM, most often related to high levels of psychological distress, sexual function, and body image or poor cosmetic outcome [12]. Montgomery et al. reported that the most common reasons for regret after CPM were a poor cosmetic outcome and diminished sense of sexuality [37].

Alternatives to CPM

Patients with unilateral breast cancer have several nonoperative options that are less invasive than CPM. Surveillance with clinical breast examination, mammography, and potentially breast MRI may detect cancers at earlier stages. Several prospective randomized trials have demonstrated that tamoxifen, given as an adjuvant therapy for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, significantly reduces the rate of contralateral breast cancer. In the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-14 study, 2,892 women with node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast tumors were randomly assigned to either tamoxifen (20 mg/d) or placebo for at least 5 years [38]. After an average follow-up of 53 months, 55 contralateral breast cancers developed in placebo-treated women and 28 developed in the tamoxifen-treated women (p = 0.001). Aromatase inhibitors also reduce the risk of contralateral breast cancer as much as, or even more than, tamoxifen [39]. The ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination) Trial demonstrated that anastrozole was superior to tamoxifen in preventing contralateral breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Ovarian ablation and cytotoxic chemotherapy also reduce the risk of contralateral breast cancer [40].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree