Introduction

Breast cancer presenting with casting type calcifications on the mammogram is one of the most unpredictable of all breast cancer subtypes.

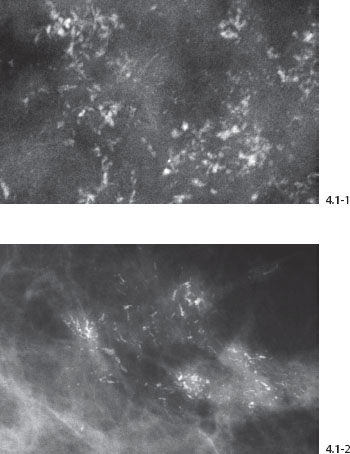

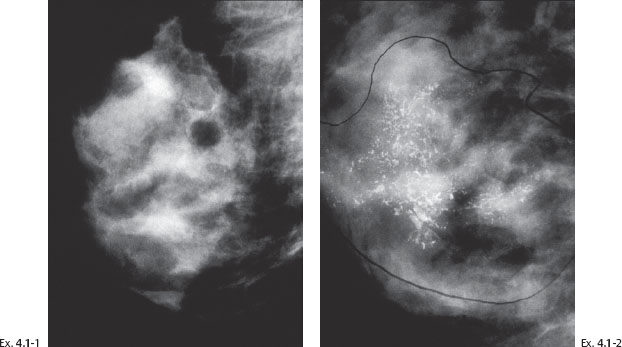

Figs. 4.1-1 & 2 Examples of fragmented casting type calcifications.

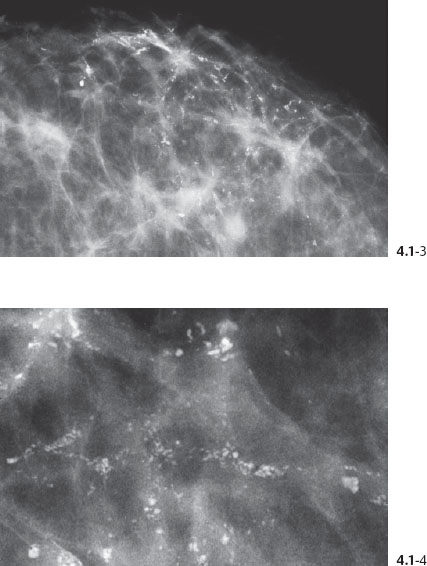

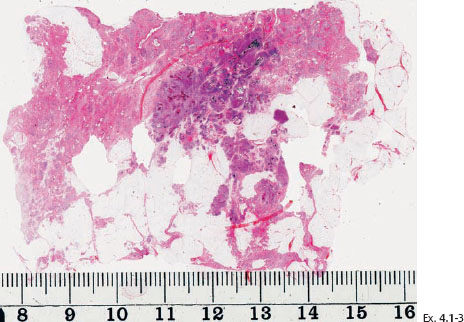

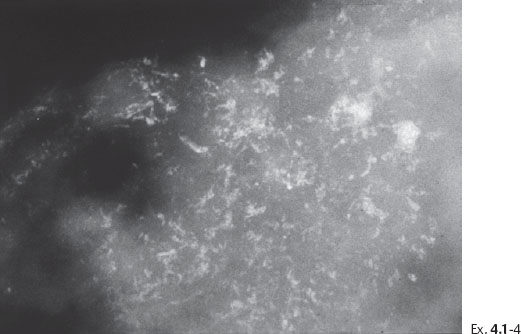

Figs. 4.1-3 & 4 Dotted casting type calcifications without and with microfocus magnification.

The Use of Mammographic Tumor Features to Study Breast Cancer

The development of an effective method of early detection combined with surgical removal of the disease has enabled the present generation of physicians to make a significant improvement in the outcome of breast cancer patients. Evaluation of both randomized controlled mammography screening trials and organized service screening programs has demonstrated a substantial and significant decrease in mortality from breast cancer as a result of diagnosis and treatment in the preclinical detectable phase.1–6 Breast cancer should be treated in its preclinical phase if we are to save women from dying of breast cancer. The decisive factor is whether the treatment is given early or late in the natural history of the disease, rather than which treatment choice is offered to breast cancer patients.7

The goal of mammographic screening is to prevent death from breast cancer. To achieve this, we have to prevent the disease from developing to an advanced stage by detecting and removing it while it is still in the 1–14 mm size range and localized to the breast (node negative). Mammographic screening can accomplish a significant change in the spectrum of the disease, which is called downward stage shifting. 8 The mortality benefit is primarily achieved by downstaging the larger invasive cancers to smaller-sized invasive carcinomas. A detailed description of a systematic strategy for finding breast cancer in its earliest detectable stages is described in the first volume of this series.9

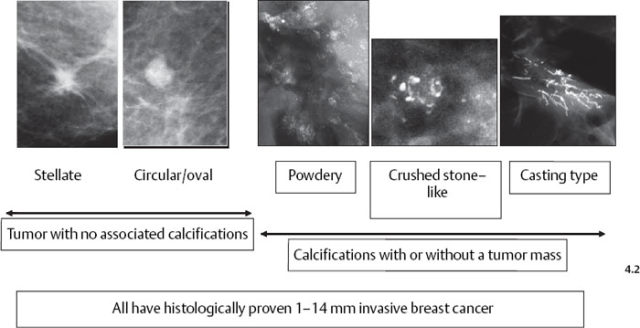

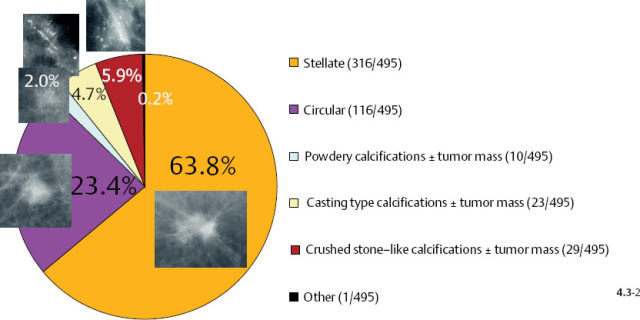

The mammographic tumor features of 1–14 mm invasive carcinomas can be classified into five distinct categories (Fig. 4.2).

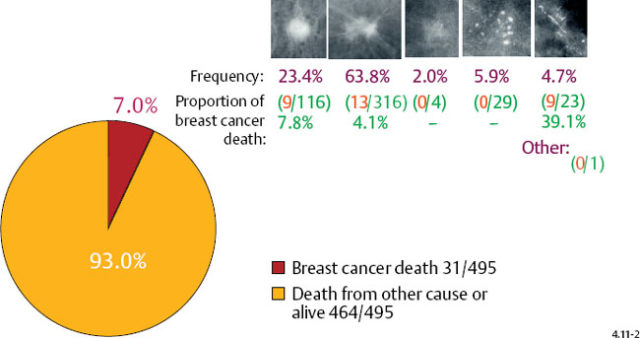

Fig. 4–2 The 1–14 mm breast cancers according to their mammographic tumor features.

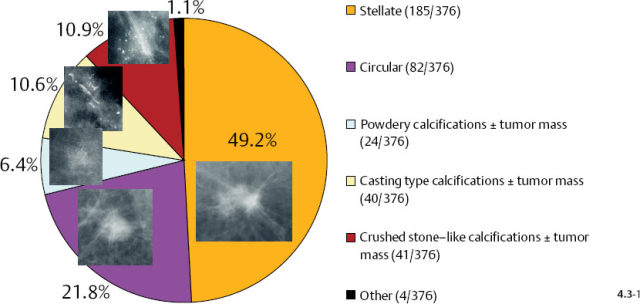

Relative Frequency of Breast Cancer Occurrence by Mammographic Tumor Features

Relative Frequency of Breast Cancer Occurrence by Mammographic Tumor Features

Stellate tumors without associated calcifications are by far the most frequently occurring mammographic subtype, followed by the circular/oval, noncalcified tumors. Casting type calcifications associated with 1–14 mm invasive carcinoma account for 7% of these tumors.

Long-Term Outcome by Mammographic Tumor Features

Long-Term Outcome by Mammographic Tumor Features

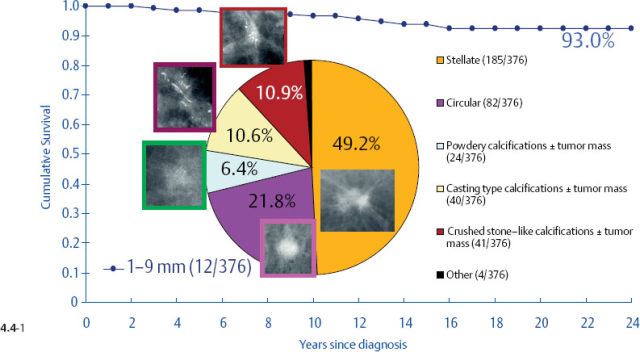

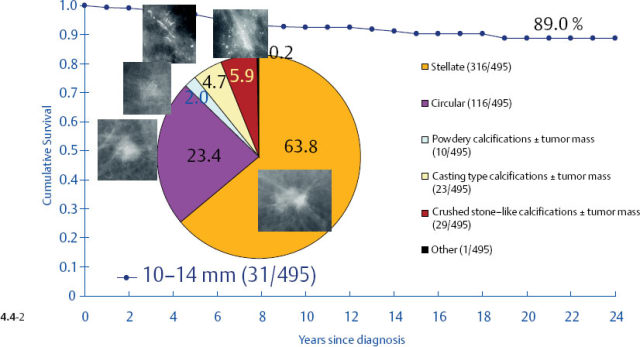

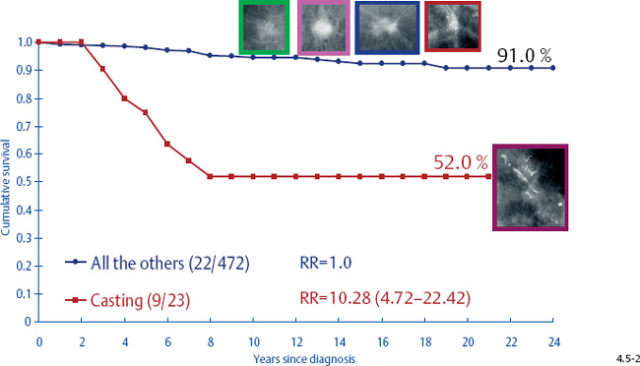

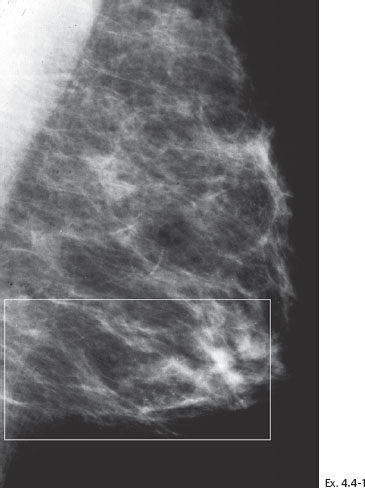

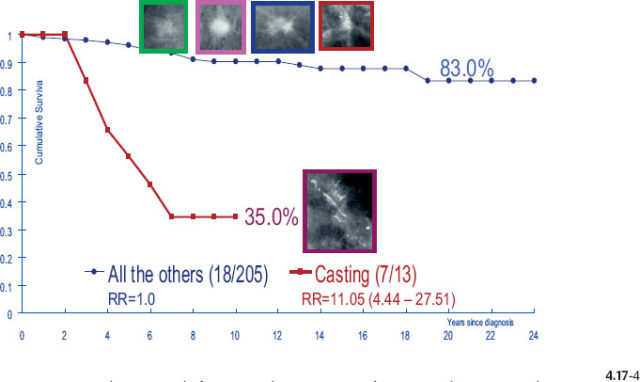

One might expect that when these different subtypes are detected at the earliest possible phase (1–9 mm and also 10–14 mm invasive tumors), each subtype would have a similar, equally excellent prognosis. This is indeed the case in four out of the five mammographic subtypes. The fifth subtype, tumors presenting with casting type calcifications, stands out in stark contrast in terms of distribution of histological prognostic factors, poor response to therapy and unexpectedly dismal prognosis. When all subtypes are lumped together, the 24-year breast cancer specific survival of 376 women with 1–9 mm invasive carcinoma is 93% (Fig. 4.4-1). However, the summation of divergent outcomes is misleading, since it includes the subtype that deviates considerably from the others in the same size group.

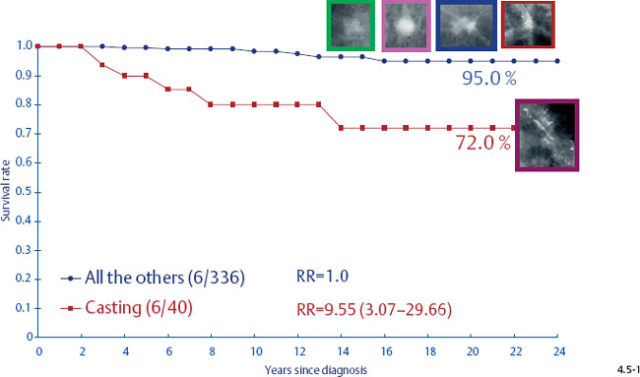

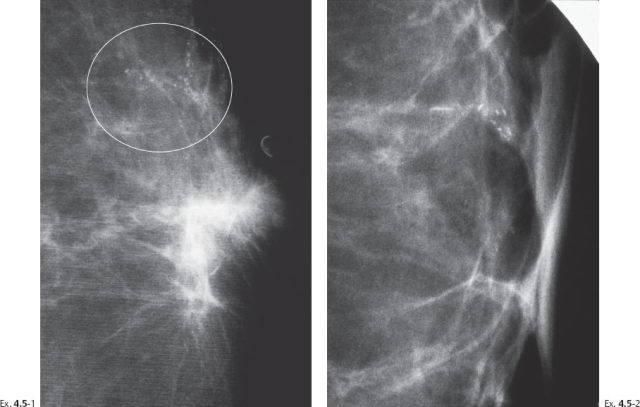

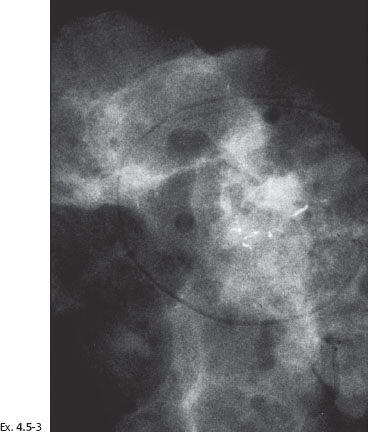

It would be a mistake to plan uniform treatment for all of these distinct subtypes based on their average survival value. When only the tumors with casting type calcifications are separated from the rest, it is apparent that the longterm outcome curves are remarkably different (Figs. 4.5-1 & 4.5-2).

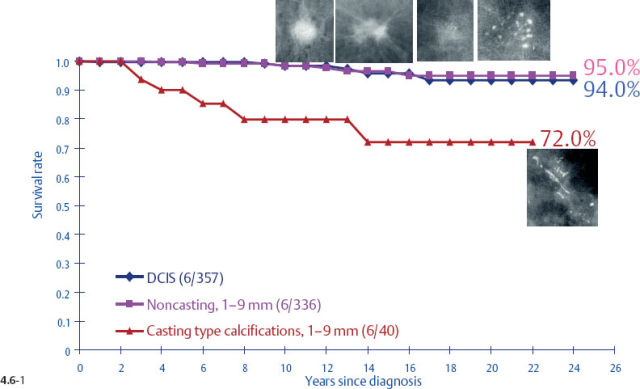

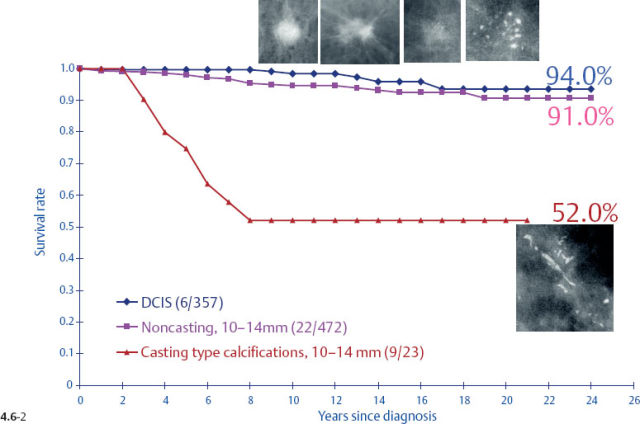

The survival of the noncasting cases compares favorably with the 24-year survival of 357 patients with DCIS, while the 1–9 mm and 10–14 mm invasive cancers associated with casting type calcifications have survival curves similar to those of large, advanced cancers (Figs. 4.6-1 & 2).

Long-Term Outcome by Mammographic Tumor Features

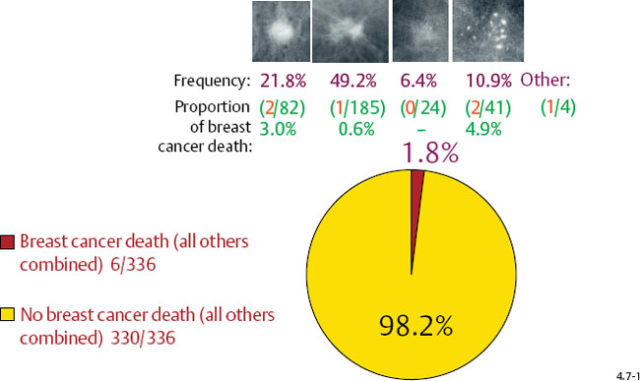

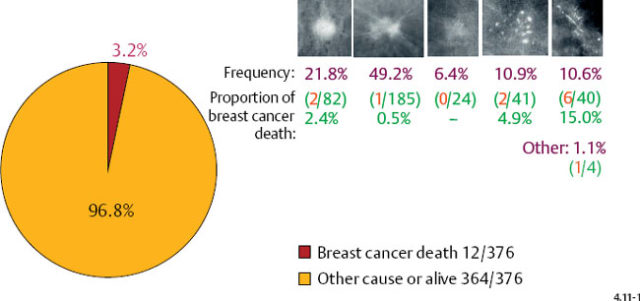

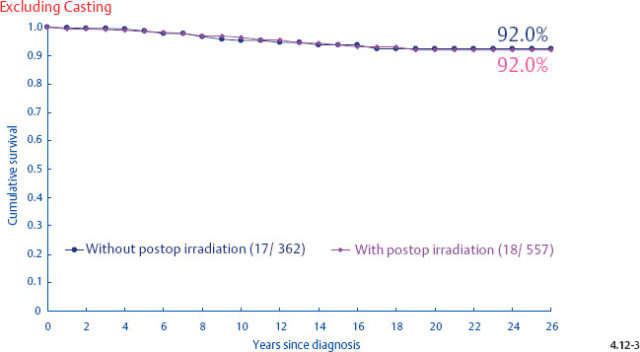

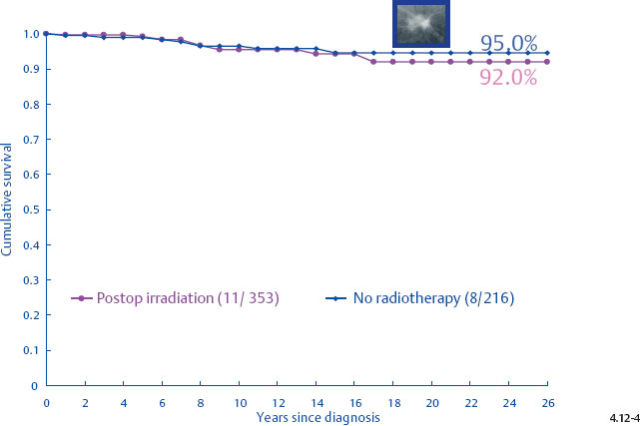

The long-term prognosis is excellent for each invasive breast cancer subtype (excluding casting), whether it is expressed as disease specific survival/case fatality rate or as proportion of breast cancer death, in both the 1–9 mm and 10–14 mm size ranges (Figs. 4.7-1 & 2).

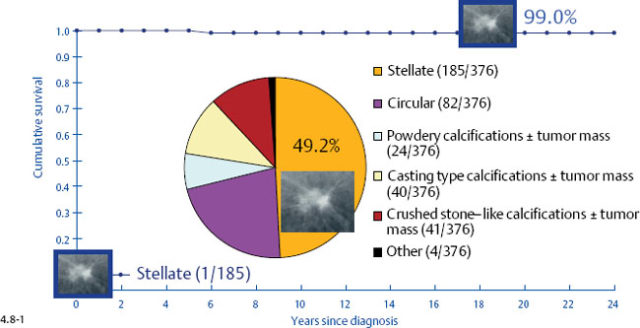

At one extreme, the subgroup of stellate tumors comprising half of the 1–9 mm invasive carcinoma cases has a 99% 24-year disease specific survival (Fig. 4.8-1).10,11 Adjuvant therapeutic regimens may offer little or no demonstrable benefit to this group.12

Long-Term Outcome by Mammographic Tumor Features

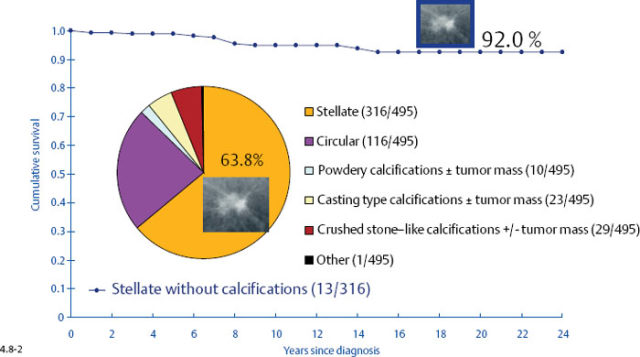

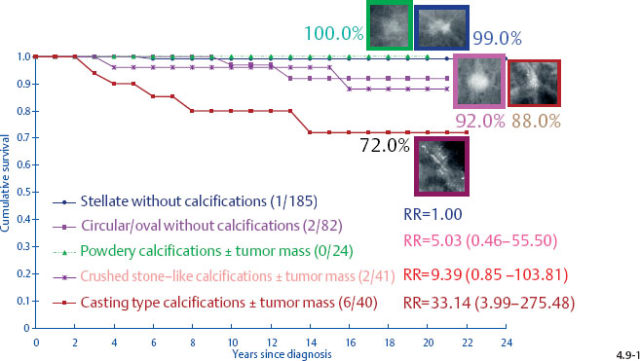

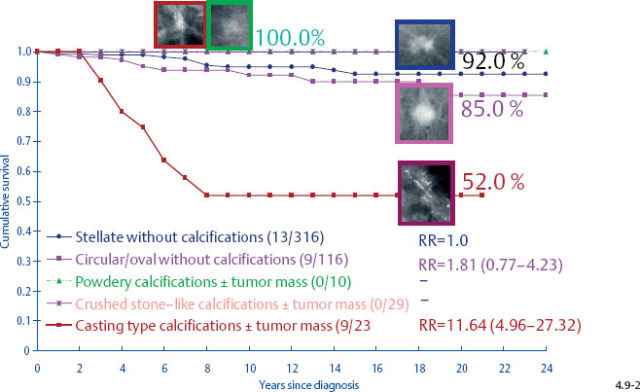

At the other extreme, the outcome of the casting cases resembles that of advanced cancers. When the long-term outcome of each subgroup is plotted separately, the majority of the 1–9 mm and 10–14 mm invasive cancers show 99–100% and 92–100% 24-year breast cancer specific survival, respectively. In contrast, the cases with casting type calcifications show a 72% and 52% 24-year breast cancer specific survival, respectively (Figs. 4.9-1 & 2).

Proportion of Breast Cancer Death by Mammographic Tumor Features

Proportion of Breast Cancer Death by Mammographic Tumor Features

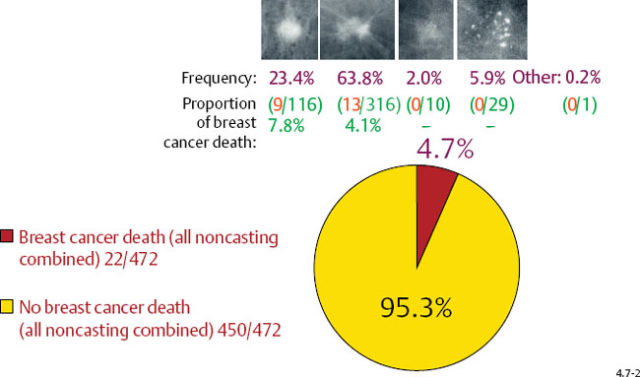

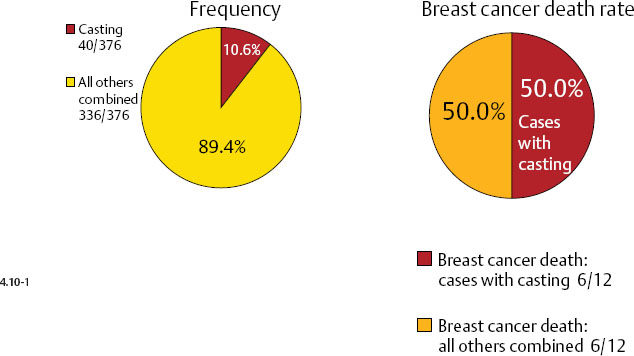

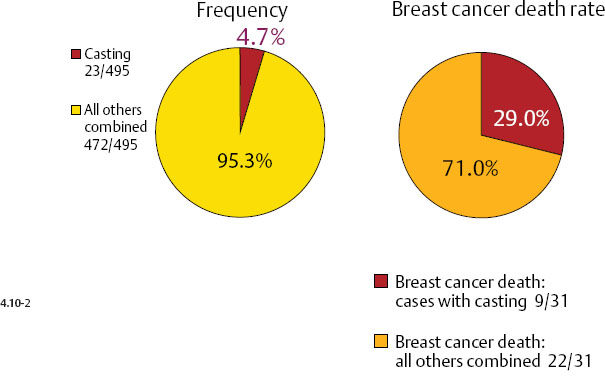

Casting type calcifications associated with invasive breast cancers account for only a small fraction of the total number of tumors in the 1–9 mm (10.6%) and 10–14 mm (4.7%) size ranges (Figs. 4.10-1 & 2), yet a disproportionately high rate of breast cancer death occurs in this subgroup. No other tumor characteristic is able to discriminate the fatal cancers in these size ranges so effectively and within such a small subgroup as is accomplished by detecting casting type calcifications on the mammogram.

No matter how the long-term outcome of women with 1–9 mm or 10–14 mm invasive breast cancer is measured, tumors associated with casting type calcifications on the mammogram stand out as by far the most lethal subgroup.

Fig. 4.11-1 Proportion of breast cancer death in women with 1–9 mm invasive cancer (3.2%). Frequency of occurrence and proportion of breast cancer death by mammographic tumor subtypes in 1–9 mm invasive breast cancers; 24-year follow-up of 376 cases.

Demonstration of Fatal Cases with Casting Type Calcifications

Example 4.1

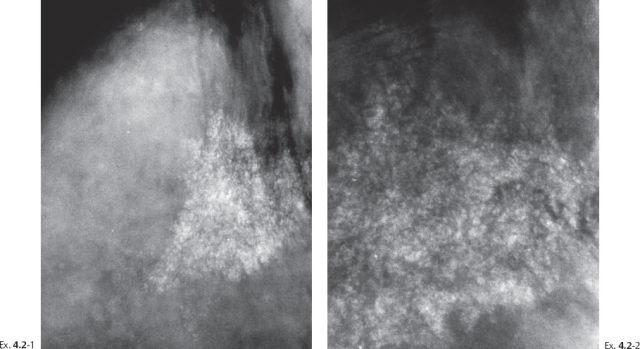

A 42-year-old asymptomatic woman, screening examination. She was called back for evaluation of the extensive calcifications appearing since the previous screening examination.

Ex. 4.1-1 & 2 Right breast, MLO projection, consecutive screening examinations at ages 40 and 42 years. No calcifications can be detected in Ex. 4.1-1. Innumerable malignant, casting type calcifications are present in Ex. 4.1-2.

Ex. 4.1-4 Microfocus magnification radiograph of a mastectomy specimen slice demonstrates innumerable dotted casting type calcifications within the closely packed ductal structures.

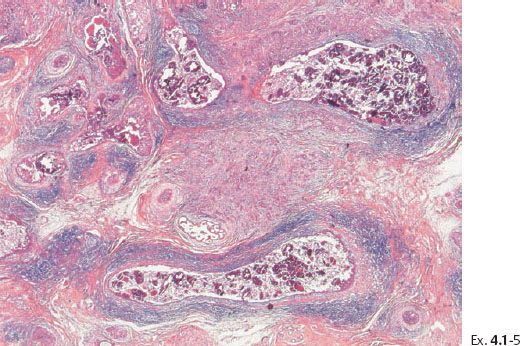

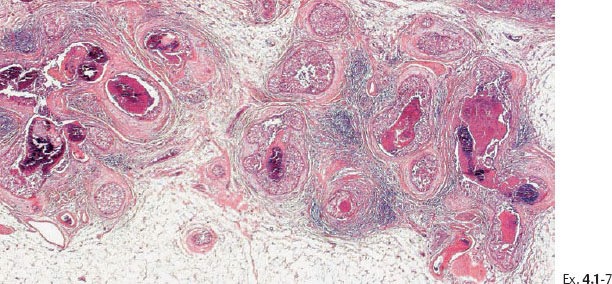

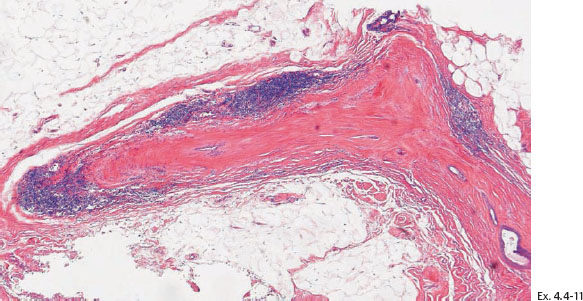

Ex. 4.1-7 Histological demonstration of the abnormally large number of closely spaced ductal structures with periductal desmoplastic reaction and lymphocytic infiltration.

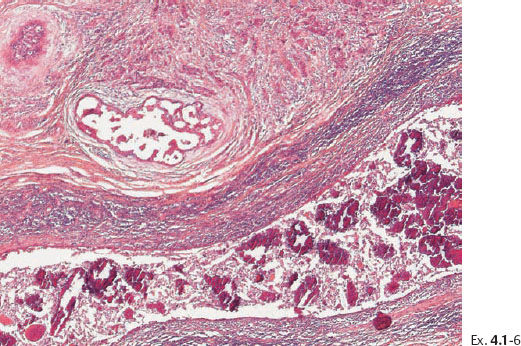

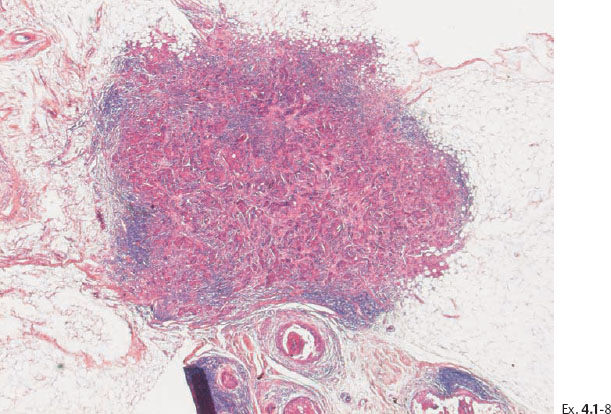

Ex. 4.1-8 Low-power image of this node-negative 10 mm Grade 2 invasive ductal carcinoma.

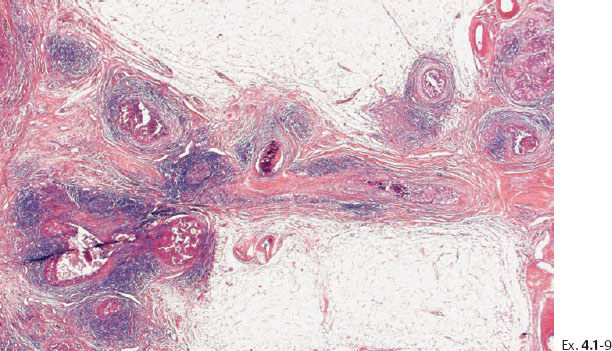

Ex. 4.1-9 Medium-power histological image of cancerous ducts with periductal reaction.

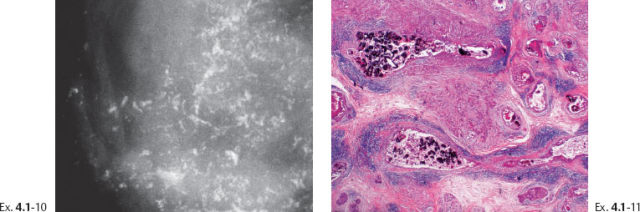

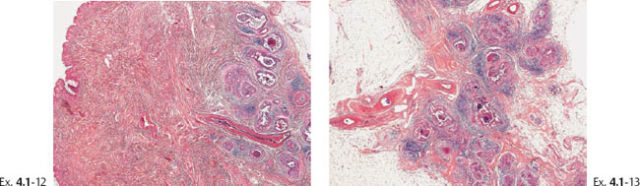

Ex. 4.1-12 & 13 The nipple and retroareolar region also contain numerous cancerous ducts.

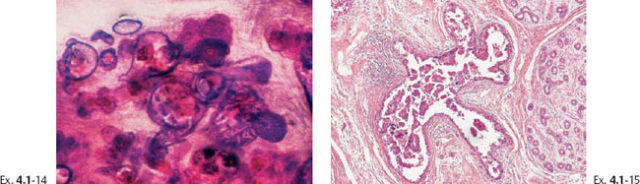

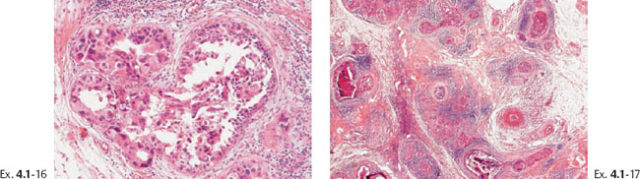

Ex. 4.1-16 & 17 Intermediate- and low-power magnification of the area with neoductgenesis.

Treatment and outcome: Mastectomy. The patient died from metastatic breast cancer 4 years and 5 months after the operation.

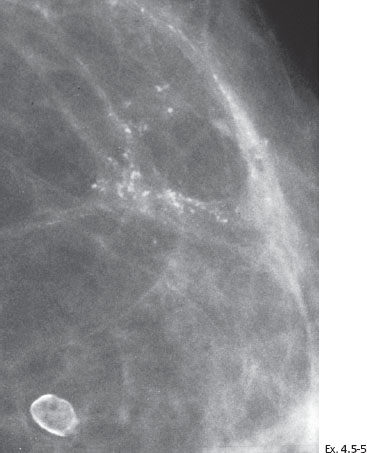

A 46-year-old asymptomatic woman, first screening examination. She was called back for evaluation of the powdery calcifications localized in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast. This occurred in 1979 when the malignant potential of powdery calcifications was not fully appreciated.

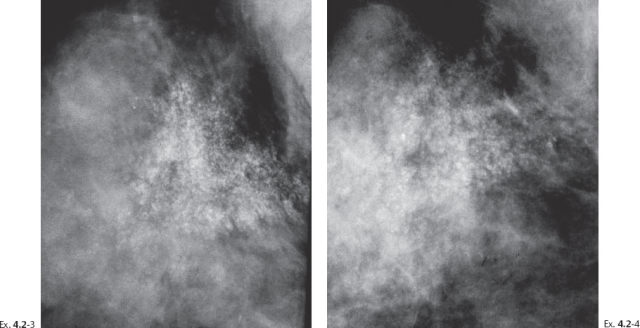

Ex. 4.2-3 & 4 Detail of the right MLO projection at subsequent screening examinations two years and seven years later. No apparent change is seen at two years (Ex. 4.2-3), but at seven years, at age 53 (Ex. 4.2-4), the calcifications appear to be diminishing in density and extent.

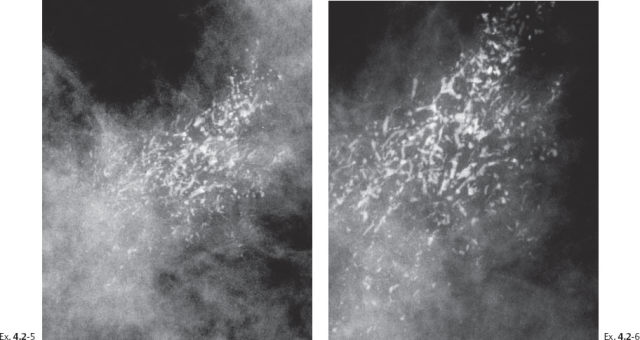

Ex. 4.2-5 & 6 Detail of the right MLO projection and microfocus magnification image at age 55. The powdery calcifications have been entirely replaced on the mammogram by a large number of casting type calcifications in exactly the same part of the breast.

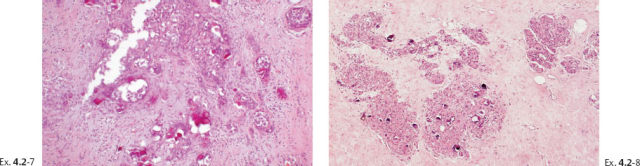

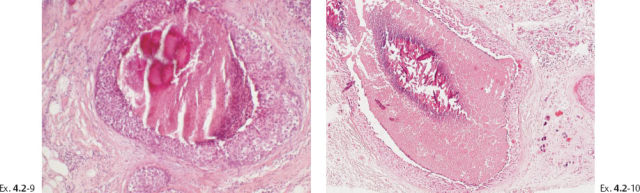

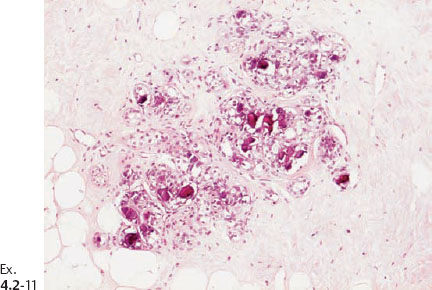

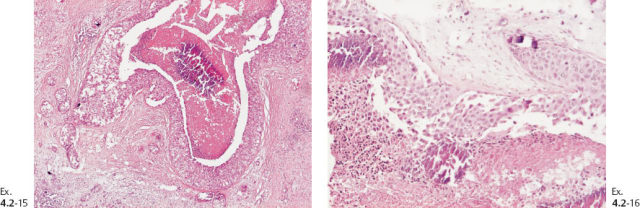

Ex. 4.2-11 Histological image (H&E) of a TDLU distended by malignant cells, amorphous calcifications and necrosis.

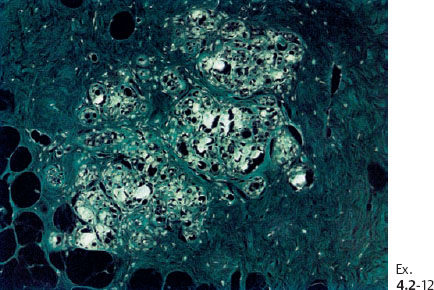

Ex. 4.2-12 The crystalline calcified structures are seen as bright spots with polarized light.

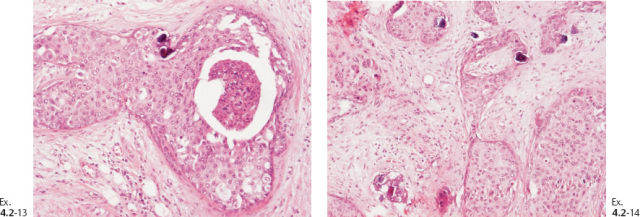

Ex. 4.2-13 & 14 Occasional psammoma body-like calcifications are scattered among the cancer cells.

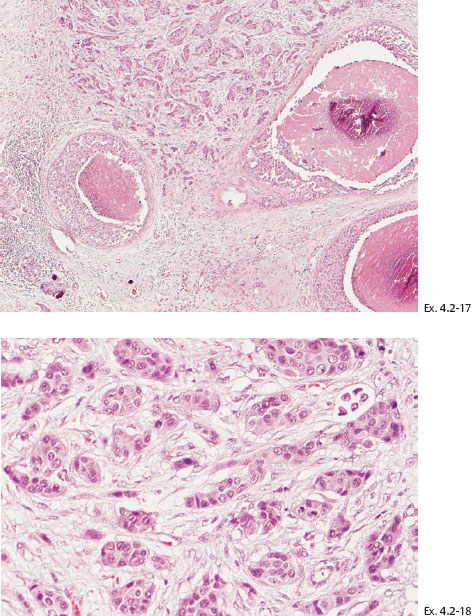

Ex. 4.2-17 & 18 Low- and intermediatemagnification histology of the 10 mm Grade 2 invasive ductal carcinoma.

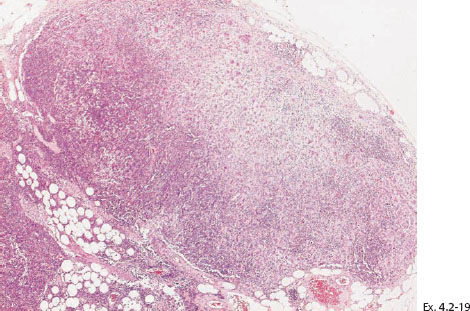

Ex. 4.2-19 The axillary lymph node contained micrometastases.

Treatment and outcome: Mastectomy. One year later the patient felt a hard lump medial to the mastectomy scar. Histology showed recurrence of the disease with extensive lymph vessel infiltration. The patient died from breast cancer 3½ years after mastectomy.

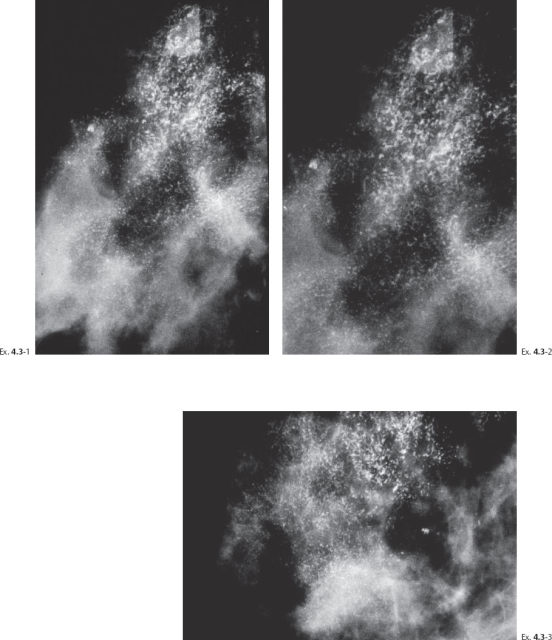

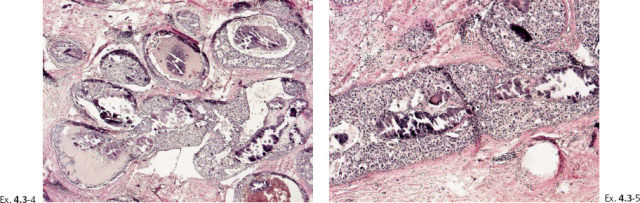

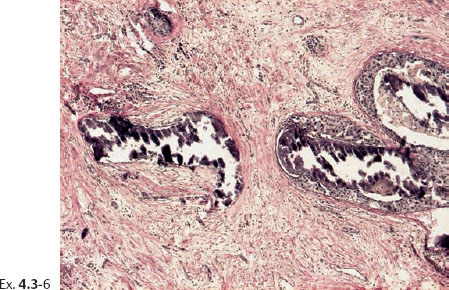

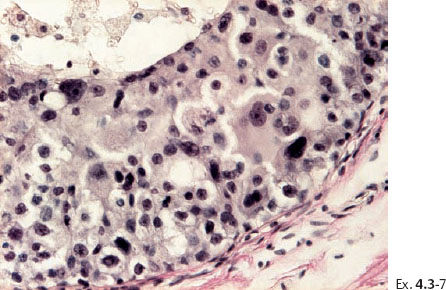

A 45-year-old woman felt a lump in the upper half of her right breast. Mammographic examination shows casting type calcifications extending over a region measuring 8 cm.

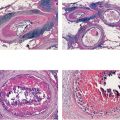

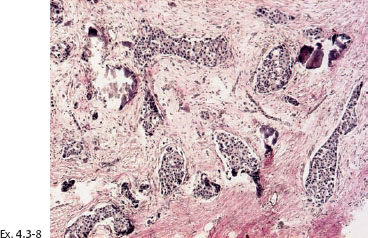

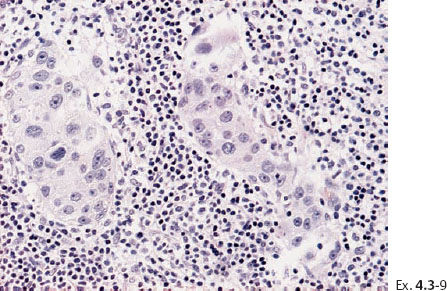

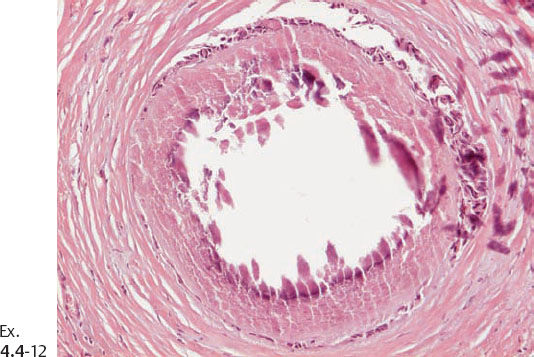

Ex. 4.3-4 & 5 The cancerous ducts seen in cross section (4) and longitudinal section (5) containing the amorphous calcifications accounting for the mammographic finding.

Ex. 4.3-6 Ducts containing casting type calcifications (van Gieson stain).

Ex. 4.3-7 High-power histology (van Gieson stain): Grade 3 insitu carcinoma.

Treatment and outcome: Mastectomy. Five years later the patient developed bone and liver metastases. The patient underwent chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. She died from breast cancer 5½ years after mastectomy.

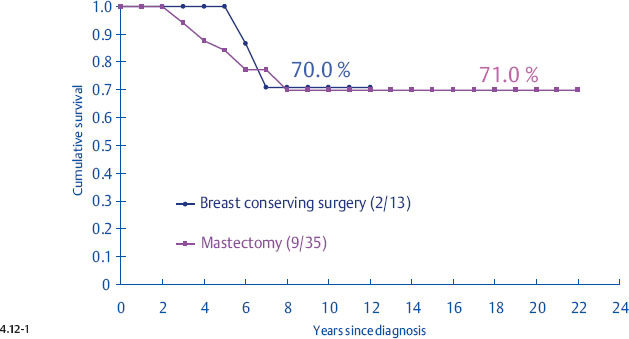

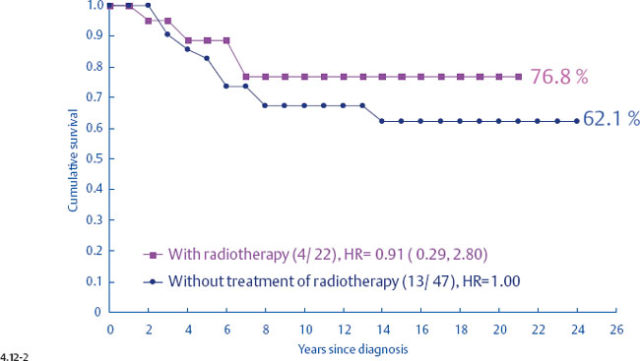

Poor Correlation of Outcome with Mode of Therapy

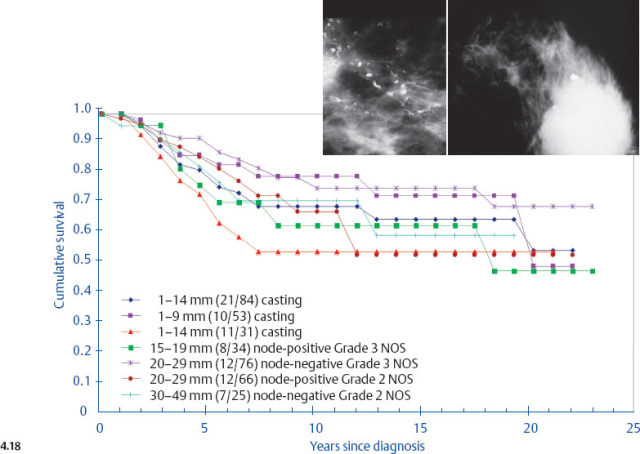

It is disappointing but not surprising that the selection of treatment appears to have little effect upon the outcome of women with casting type calcifications associated with 1–14 mm invasive breast cancers. The clinical outcome of this breast cancer subtype is very similar to that of advanced, stage II-IV breast cancers (Fig. 4.18, p. 226), and there is sufficient evidence showing that therapeutic regimens have a limited impact upon the final outcome of such breast cancer cases.13–14

In particular, the largest group of women with 1–14 mm invasive breast cancers, those with stellate tumors not associated with calcifications, appear to receive no survival benefit from postoperative radiation.

Demonstration of Local Recurrence Following Radiotherapy

Example 4.4–4 to 8

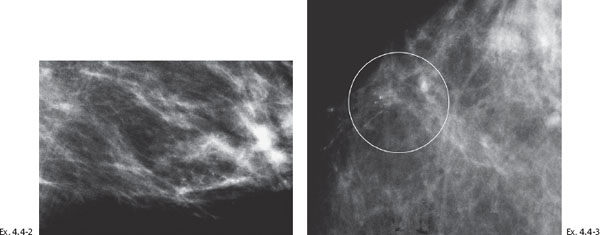

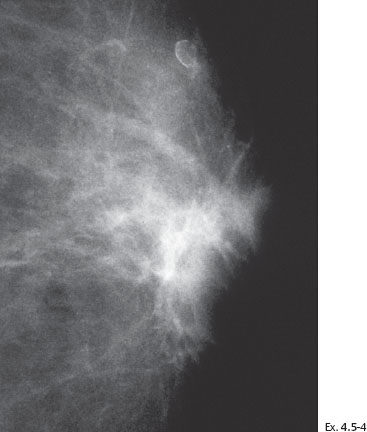

A 59-year old asymptomatic woman, screening examination. A small cluster of calcifications, which was overlooked, is seen retrospectively in the lower inner quadrant of the left breast.

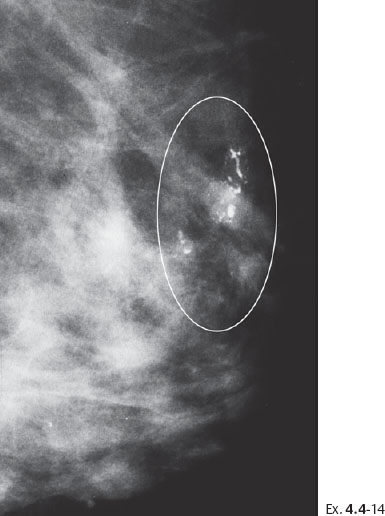

The next screening examination was at age 60, still asymptomatic. The calcifications are more prominent and are now of the casting type.

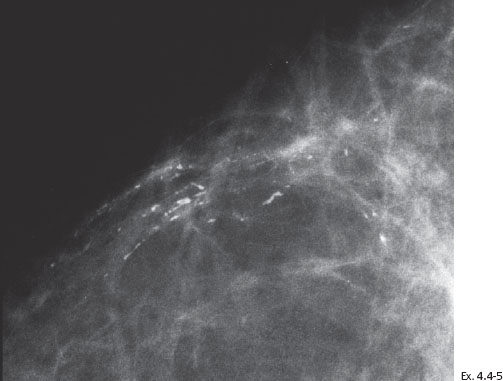

Ex. 4.4-4 Detail of the left MLO and CC projections one year later. Casting type calcifications are localized in the lower inner quadrant in an area measuring at least 4 cm in diameter.

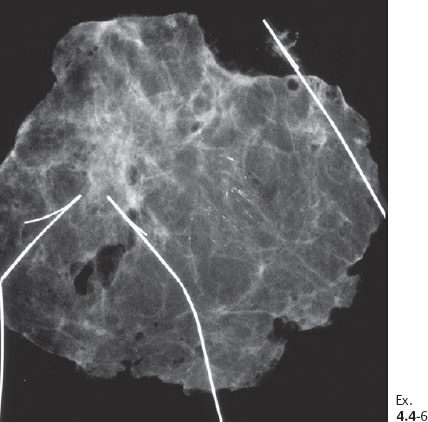

Ex. 4.4-6 Specimen radiograph (8 cm × 8 cm surgical specimen) without microfocus magnification: the calcifications have been removed with a good margin.

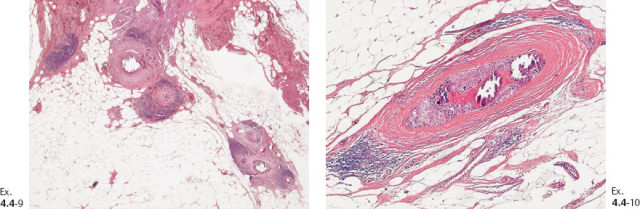

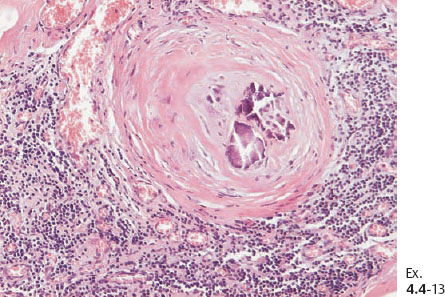

Ex. 4.4-9 & 10 Histology (H&E): 40 mm × 30 mm Grade 3 DCIS. No sign of invasion.

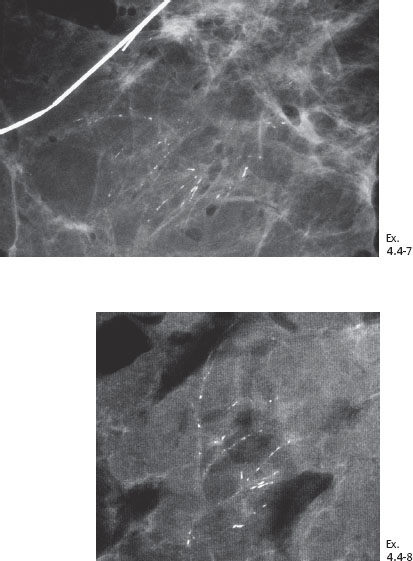

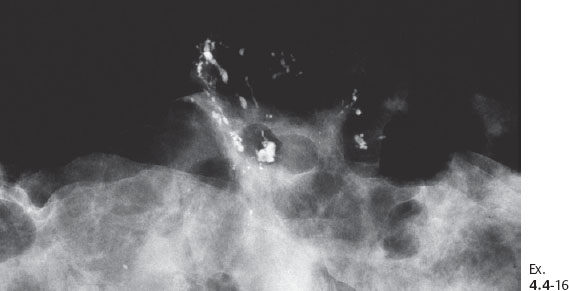

Ex. 4.4-14 The patient received postoperative irradiation. Follow-up mammography two years after segmentectomy and postoperative irradiation: a new cluster of casting type calcifications is seen in the subcutaneous retroareolar region, at the upper border of the areola, distant to the site of operation.

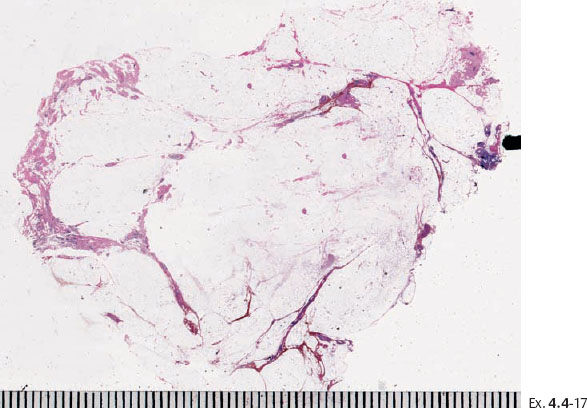

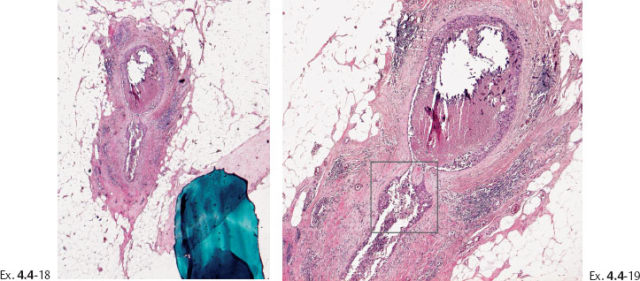

Ex. 4.4-17 Large-section histology showing the cancerous ducts with intraluminal calcifications on the specimen margin.

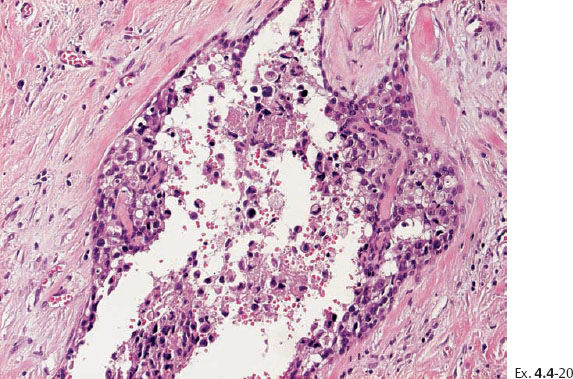

Ex. 4.4-20 High-power histological image (H&E) of the area within the rectangle on Ex. 4.4-19. Grade 3 in-situ carcinoma.

Follow-up: Five years after the initial operation and radiotherapy and three years after recurrence and mastectomy, the patient is alive and well.

(Case courtesy of Urpo Saari, M.D., Tyräskylä, Finland) This case also represents a recurrence after segmentectomy and postoperative radiotherapy.

Ex. 4.5-3 Specimen radiograph. The calcifications described on the mammogram are close to the tissue margin. Postoperative irradiation was given after this sector resection.

Treatment and follow-up: Mastectomy. The patient is lost to follow-up.

Axillary Node Status and Mammographic Tumor Features

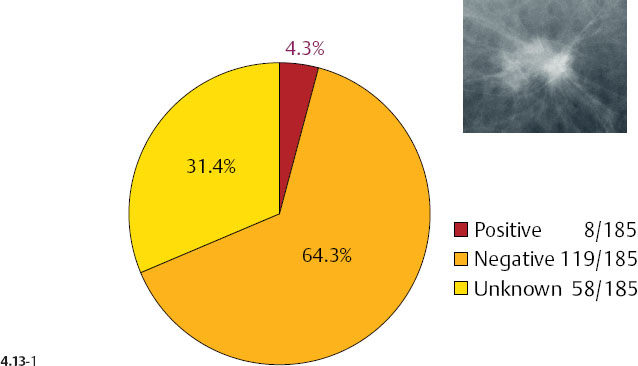

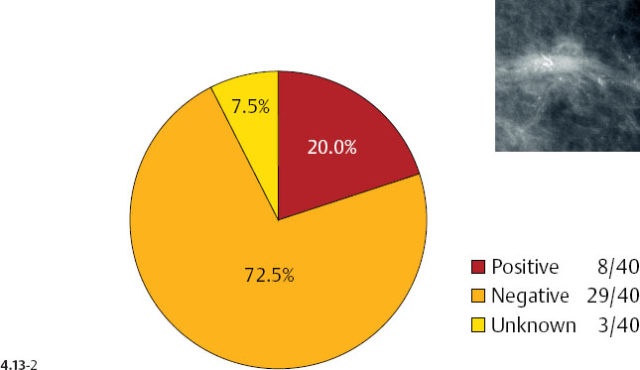

There is a remarkable difference in axillary node positivity according to mammographic tumor features (Figs. 4.13-1 & 2). Only 4.3% of women with 1–9 mm stellate cancers had positive axillary nodes (and 0.5% died of breast cancer) compared with 20% node positivity in tumors associated with casting type calcifications, of whom 15% (6/40) died from breast cancer.

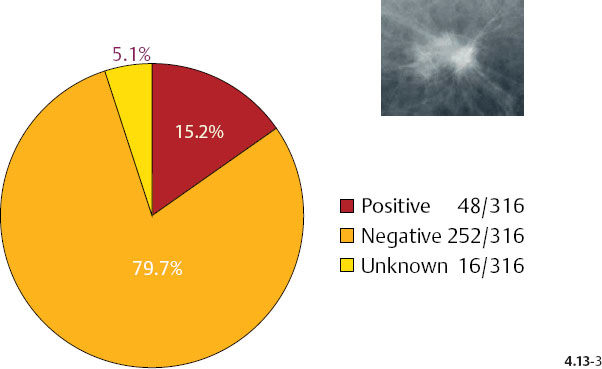

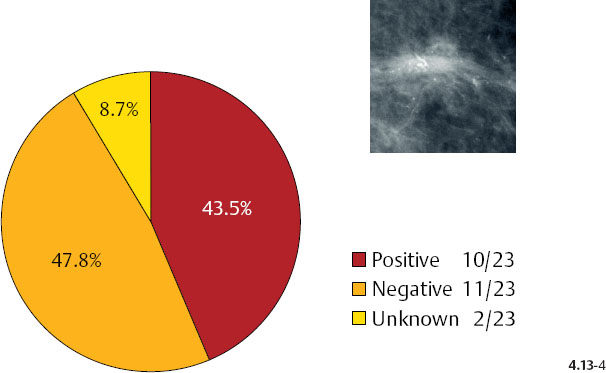

As the stellate tumor size increases to 10–14 mm, the node positivity rate increases to 15.2%. In the tumors of similar size, but associated with casting type calcifications, the unexpectedly high rate of node positivity (43.5%) emphasizes the deviant nature of these tumors (Figs. 4.13-3 & 4).

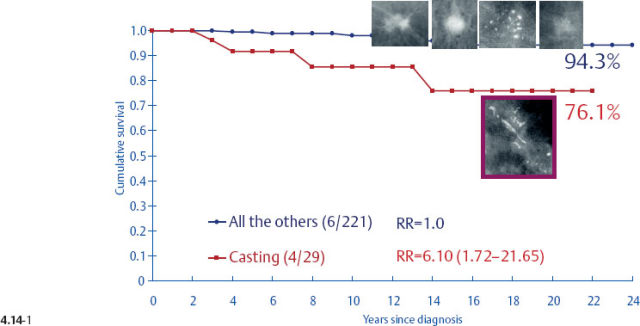

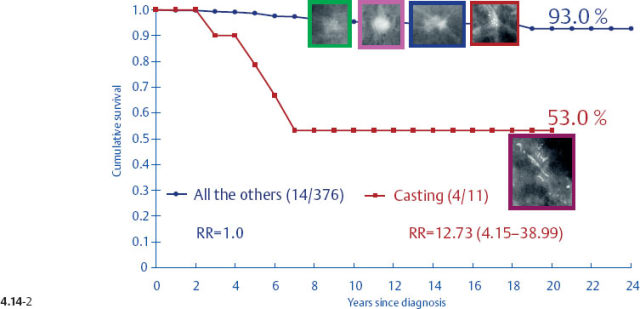

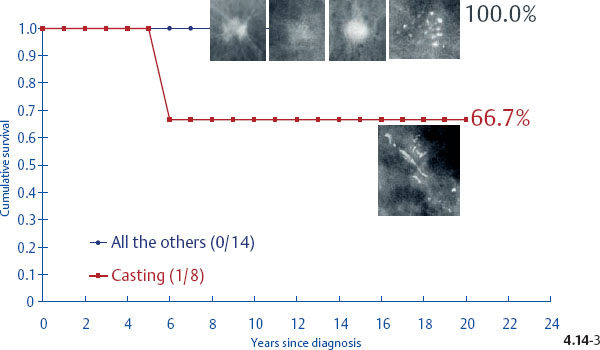

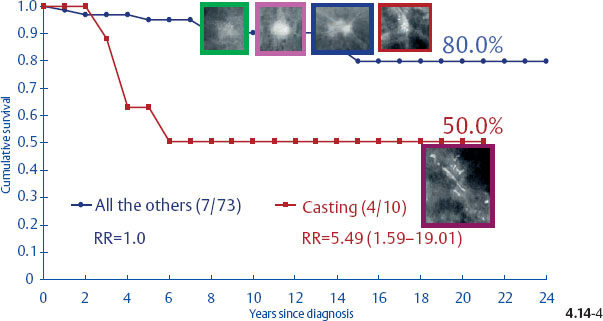

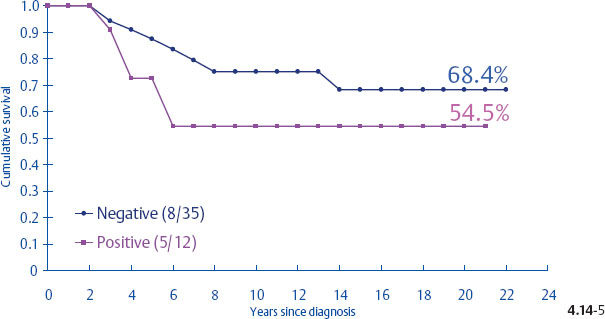

Surprisingly, the conventional prognostic factors of axillary node status and histological malignancy grade do not predict the long-term outcome of 1–14 mm invasive breast cancers associated with casting type calcifications. The unreliability of the axillary node status in predicting the longterm survival of women with 1–9 mm and 10–14 mm invasive breast cancers is demonstrated in terms of the mammographic tumor features in Figs. 4.14-1 to 5. In the absence of casting type calcifications, the vast majority of women with 1–14 mm invasive breast cancers will have excellent longterm survival, even those few with node-positive 1–9 mm invasive tumors. A surprising finding is the consistently poor outcome of women with 1–14 mm invasive cancer associated with casting type calcifications, regardless of node status (Fig. 4.14-5). These findings demonstrate that the node status in 1–14 mm invasive breast cancers is a much less reliable prognostic factor than it is for larger tumors.

Fig. 4.14-3 Cumulative 24-year disease specific survival of women with node-positive 1–9 mm invasive breast cancer by mammographic tumor features.

Histological Malignancy Grade and Mammographic Tumor Features

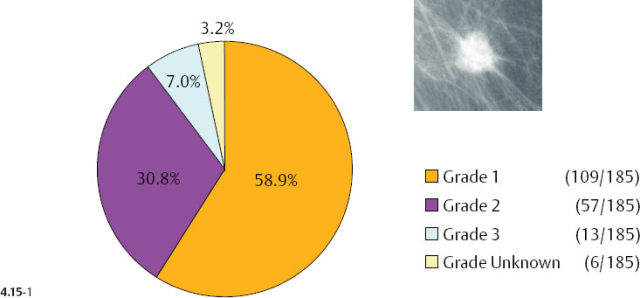

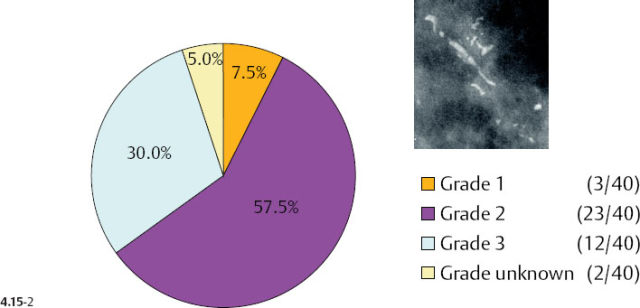

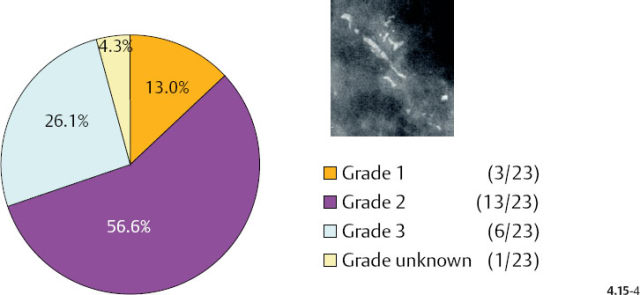

Additionally, there is a considerable difference in the distribution of histological malignancy grade according to mammographic tumor features (Figs. 4.15-1 & 2): 38% of the 1–9 mm stellate cancers were Grade 2 and 3, whereas 88% of the tumors associated with casting type calcifications were of Grade 2 and 3 in our consecutive series of cases diagnosed from 1977 to 2001. Although the casting type calcifications represent a Grade 3 intraductal malignant process, note that the majority of the associated 1–9 mm invasive carcinomas are Grade 2.

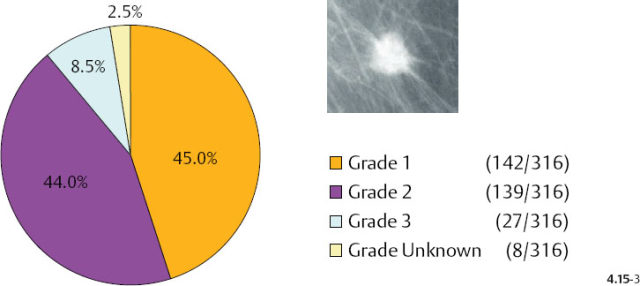

As the stellate tumor size range increases to 10–14 mm, the frequency of Grade 2 and 3 tumors also increases (from 38% to 53%) at the expense of the Grade 1 tumors. In the tumors of similar size, but associated with casting type calcifications, the very high rate of Grade 2 and 3 tumors remains essentially unchanged (88% vs. 83%) (Figs. 4.15-3 & 4). The most important finding is that the majority of the 10–14 mm invasive carcinomas associated with casting type calcifications are Grade 2.

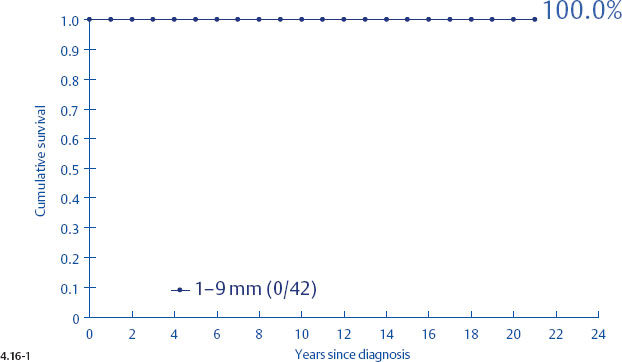

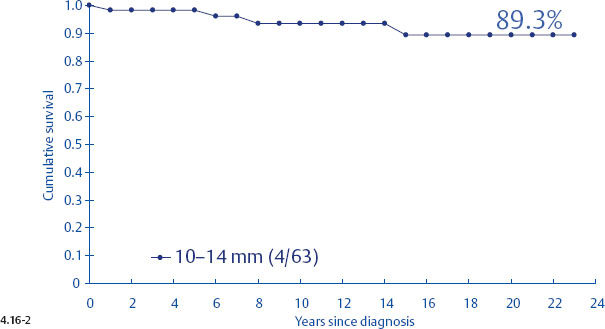

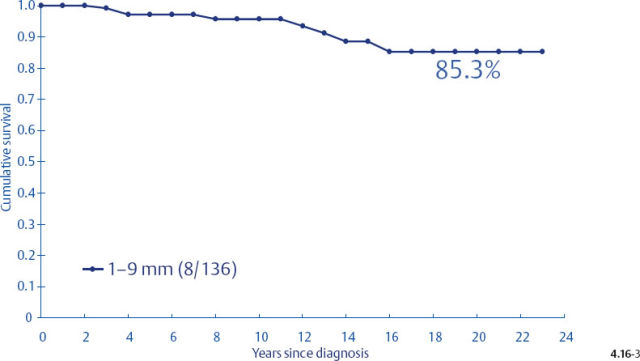

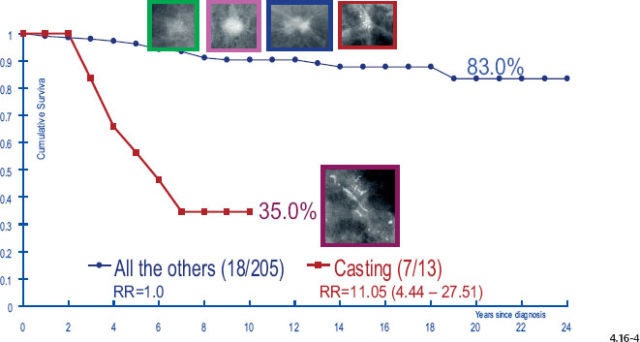

Unfortunately, the histological malignancy grade also loses its reliability in predicting the long term outcome of women with 1–9 mm and 10–14 mm invasive breast cancers15,16 (Figs. 4.16-1 to 4). One would expect that women with Grade 3 tumors would have a poorer long-term outcome, but there was a 100% disease specific survival in the 1–9 mm tumor size range. Even in the size range of 10–14 mm, the Grade 3 tumors had a better outcome than the 1–9 mm Grade 2 tumors.

Fig. 4.16-1 Cumulative survival of women with 1–9 mm Grade 3 invasive breast cancer.

Fig. 4.16-2 Cumulative survival of women with 10–14 mm Grade 3 invasive breast cancer.

Figs. 4.16-3&4 show the surprisingly poorer long-term outcome of women with 1–9 mm and 10–14 mm Grade 2 invasive breast cancers compared to those with Grade 3 tumors (Figs. 4.16-1 &2). These observations should cause us to critically examine the value of the histological malignancy grade as a prognostic factor.

Fig. 4.16-3 Cumulative survival of women with 1–9 mm Grade 2 invasive breast cancer.

Fig. 4.16-4 Cumulative survival of women with 10–14 mm Grade 2 invasive breast cancer.

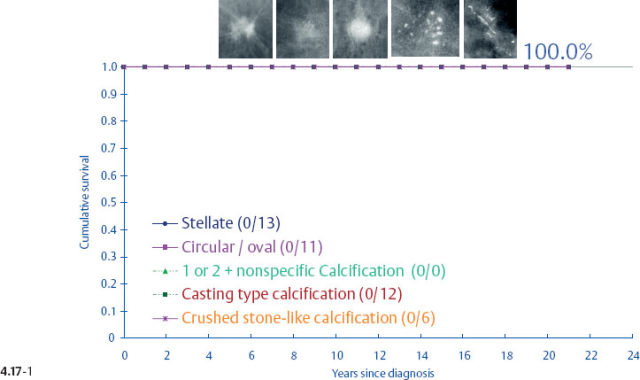

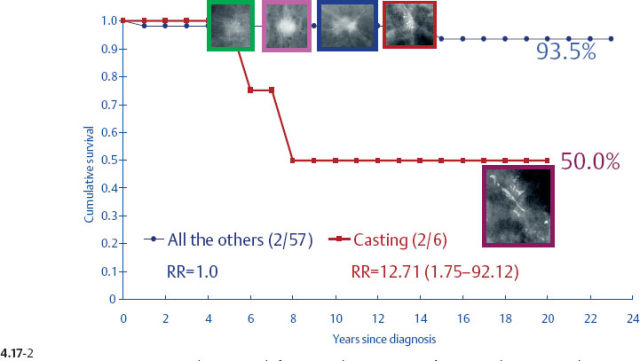

When plotting the survival curves of 1–9 mm Grade 3 tumors (Fig. 4.17-1), the absence of breast cancer death in any of the subgroups precludes further division. In the size group of 10–14 mm (Fig. 4.17-2), one observes 2 breast cancer deaths among the 57 cases not containing casting type calcifications (93.5% 24-year survival), and also 2 breast cancer deaths among only 6 women with invasive tumors of identical size and histological grade but associated with casting type calcifications (50.0% 24-year survival).

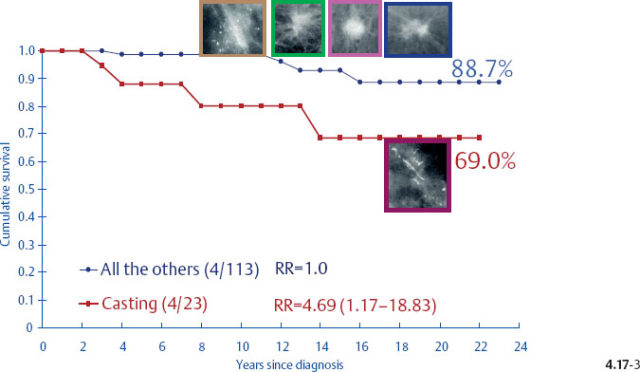

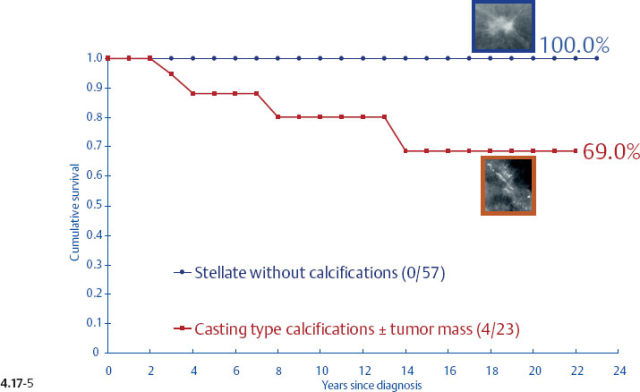

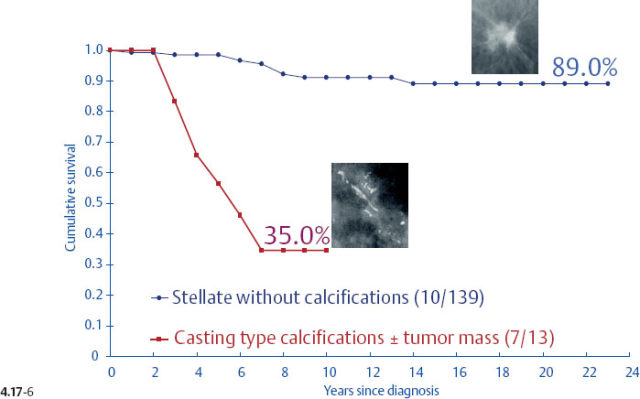

The divergent behavior of the 1–9 mm and 10–14 mm Grade 2 tumors associated with casting type calcifications demonstrated in Figs. 4.17-3 & 4 (previous page) is further emphasized when comparing the outcome of the largest subgroup, stellate tumors without associated calcifications, against the outcome of tumors associated with casting type calcifications.

While axillary node status and malignancy grade are wellestablished and reliable prognostic factors in tumors > 20 mm, their prognostic reliability appears to diminish with decreasing tumor size.

- Women with 1–9 mm Grade 2 stellate invasive carcinomas without associated casting type calcifications have excellent 24-year survival (Figs. 4.17-5 & 6).

- Since women with tumors of the same size category and histological grade associated with casting type calcifications have a dismal prognosis, the associated Grade 2 invasive component cannot by itself be responsible for the poor outcome. The same conclusion applies to the 10–14 mm size category.

- The large tumor burden contained within the region of several centimeters size with casting type calcifications must therefore be responsible for the poor outcome in these cases, even if it is currently classified as an in-situ component.

- We propose that the casting type calcifications represent both an in-situ carcinoma (when the cancer cells are confined within the preexisting duct system) and also a “duct forming high-grade invasive carcinoma,” where the cancer cells are situated within the newly formed ducts, mimicking the adjacent in-situ process. This process of neoductgenesis appears to account for the significant, potentially harmful portion of the tumor burden.

- The discrepancy between the long-term survival of women with 1–14 mm Grade 3 and Grade 2 invasive breast cancers can be explained by the fact that most 1–14 mm invasive breast cancer cases with associated casting type calcifications are histological Grade 2, and include most of the fatal cases (Figs. 4.15-1 to 4, 4.16-1 to 4.17-1 to 6). This may give the false impression that the histological Grade 2 is a more fatal disease than Grade 3. However, it is the duct forming high-grade malignant process that must be responsible for the high fatality rate.

- It is generally accepted that the patient outcome is determined by the histological features of the small invasive tumor, regardless of whether there is an associated in-situ component. This assumption leads to confusion concerning this particular breast cancer subtype, where the in-situ component is characterized by casting type calcifications. This is because in the majority of the cases the invasive component is a 1–14 mm Grade 2 tumor, which should otherwise have an excellent prognosis in the absence of casting type calcifications. The surprisingly poor outcome of these cases cannot be attributed to the histological features of the small, Grade 2 invasive component.

- One consequence of attributing the poor outcome to the small, nonpalpable invasive component, while underestimating the true nature of the complex conglomerate consisting of Grade 3 DCIS and duct forming high-grade invasive carcinoma shown on the mammogram as casting type calcifications, is frequent recurrence and poor outcome despite adjuvant therapeutic regimens. Another consequence of this assumption is the currently inappropriate TNM classification, whereby breast cancer death is considered to have been caused by, for example, a T1a Grade 2 invasive tumor. This in turn gives the mistaken impression that some “small” breast cancers are systemic from their inception.17

- The failure to discriminate between the two extremes of outcome within the 1–14 mm invasive breast cancer group has lead to overtreatment of the majority of 1–14 mm breast cancers, since the therapeutic guidelines are based on the aggregated outcome data, combining cancers having truly excellent long-term survival (the majority) with cancers having a high short-term fatality rate (the minority).18

Outcome of 1–14 mm Casting Cases Compared with Advanced Cancers

There is a striking similarity between the breast cancer specific survival curves of the 1–9 mm and 10–14 mm invasive tumors associated with casting type calcifications and the outcome curves of much larger, advanced breast cancers (Fig. 4.18). The similarity in outcome of tumors that have been classified as T1a and T1b to the outcome of advanced cancers should prompt us to resolve this discrepancy. Reports confirming the poor outcome of small invasive cancers associated with casting type calcifications give further credence to the importance of this topic.10,16–22 If the vast majority of women with 1–9 mm and 10–14 mm breast cancers have excellent long-term survival, as demonstrated in previous figures (pages 220–224), yet one well-defined subgroup in the same size category has a long-term outcome indistinguishable from that of advanced cancers, the inescapable conclusion must be that we are dealing with a disease subgroup that in reality acts like an advanced cancer. Because this tumor behaves like an advanced cancer, the policy of calling it a 1–9 mm or 10–14 mm invasive cancer must be in error. After all, it is the long-term clinical behaviorof a tumor subgroup that reveals its true nature, which should also determine its place in the TNM staging classification. Unfortunately, the present classification system fails to provide an accurate match between the characteristics of this tumor subtype and the eventual patient outcome.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>