If a group of people don’t already share knowledge, don’t already have plenty of contact, don’t already understand what insight and information will be useful to each other, information technology is not likely to create it.

Introduction

The diabetes nurse educator requires technologies to support day-to-day activities and to successfully reach patient-focused behavioural objectives. Although use of technologies in health is pervasive, it may soon become ubiquitous. This chapter outlines current uses of healthcare information technology (HIT) and technological solutions the diabetes nurse educator will need in the near future for education, management and self-care of their patients.

Internet and networks

Although present day information technology (IT) owes its existence to converged Victorian-era inventions, the telegraph and telephone, weaving the Web into a superhighway arises as a unique feat comparable to Gutenberg’s press, Bell’s telephone and Marconi’s radio. We envision the superhighway as an environment where most citizens walk. At the same time, many people fear that technology is dehumanising us by taking away creative aspects of personality, or compassion and sensitivity towards others, but Michael Dertouzos elegantly phrased that technology is an inseparable child of humanity and for true progress to occur the two must walk hand in hand (Berners-Lee 2000).

The exchange of information in networks before the Web thrived on a decentralised technical, as well as social, architecture. Web 1.0 allows users to retrieve information, but linking all the information stored in computers everywhere will not find the solution to our problems, although the Web is capable of performing the bulk of the legwork required. Tim Berners-Lee, the creator of this Web, pointed out that information retrieval gets things done faster, but exhausts us in the process. Therefore, reaching desired goals will not emerge spontaneously from information abundance, although diabetes educators become more competent and citizens empowered through access to a much wider range of information.

Learning is a remarkably social process and information is only one of the pieces in creating progress. Documents do not merely carry information, but enable virtual communities among those who share information to reach common understanding and new concepts. Since traditional communities have mostly declined, networks may develop a sense of belonging if they can create an image of the group as a single community.

Web 2.0 sites allow users to do more than just retrieve information by providing the user with a platform for community collaboration by blogs and wikis. Facebook aptly describes its social dimension and these forms of cooperation, provided that privacy is protected by encrypted communication and secure identification, may apply for multidisciplinary working groups and interactions with diabetics. Because citizens have changed more than the organisations on which they depend, these new working models could tailor services individually according to personalised need.

What the social media models are enabling is decentralised individual communication (Mezrich 2010). The ability to create and update content leads to the collaborative work of many rather than just a few. This paradigm will allow people to get more of their information through constant updating in this network. Another approach to be provided by the semantic Web (Web 3.0) is driving the evolution of the current Web and allowing users not only to find, share and combine information more easily, but also enable data on the Web to be located and processed automatically on behalf of the user.

As we seem to be naturally built to interact with others, it is necessary to identify that this reciprocity takes various forms. Two types of work-related networks, with the boundaries they inevitably create, are critical for understanding learning, work and the movement of knowledge (Brown and Duguid 2002). First, there are the networks that link people to others whom they may never get to know but who work on similar practices or are amalgamated by shared caring for diabetics. These are the ‘networks of practices’ and they are notable for their reach, which may be fortified by information technology. Although these networks produce little new explicit knowledge, they are operationally very efficient in supplementing tacit and collective learning to this process. Scaling and outsourcing of services, driven and supported partly by developments in IT, has become established policy in many countries multiplying the complexity of these service networks.

Second, there are the more tight-knit groups formed, again through practice, by people working together on the same or similar tasks. These are what we call ‘communities of practice’. Here coordination is tight, and ideas and knowledge are distributed in productive and innovative fashion. While information technology and information sharing is very good in reach, it may suit less well to the dense interaction already in place between practices in the same unit.

Diabetes education

Patient-focused chronic care means that healthcare is organised to maximise the effectiveness of patients to manage their chronic illness themselves. Effective and efficient methods of management, particularly in home care and community-based services, have been devised that enhance the ability of patients with chronic care to participate in their healthcare (Holman and Lorig 2000). Three programmes place patients in a central role in their healthcare—self-management education, group visits and remote medical management.

Educational programmes have become an integral part of diabetes care, but despite the fact that comprehensive implementation of diabetes education remains an outstanding unmet need (Grusser 2011), HIT has not been applied in self-management education to a greater extent as catalyst for successful diabetes therapy. Providing information to patients for dealing with medical management, emotional management and role management is insufficient on its own to improve clinical outcomes (Murray 2008a). Paradoxically at times, the patient may appear ‘more informed’, especially if their condition is chronic as in diabetes. This may arouse defensible reactions (legitimate and appropriate) from professionals towards the exploitation of HIT.

Besides acquiring knowledge and skills as outcomes of diabetes self-management education, behaviour changes such as developing confidence, motivation and problem-solving skills to perform self-care and overcome barriers have been adopted for effectiveness of diabetes education (Mulcahy et al. 2003). The role of HIT may be partly seen in essence as a support and enabler of lifestyle and behaviour management of the diabetic by the following:

- Health information services that provide general and specific information and guidance (http://www.nhs.uk/Pages/HomePage.aspx, http://ndep.nih.gov/, http://www.ndei.org/)

- Peer communities for interaction among citizens or patients about shared health concerns; a form of social media (http://www.peersforprogress.org/about_us.php)

Several objectives, extending from commercial incentives to academic motivation, exist when diabetes education material is made available on the Web. The problem is no longer finding information but assessing the credibility of the publisher as well as the relevance and accuracy of a document retrieved from the Net. Content has to be appropriate and evaluated to the intended need. A site sponsored or facilitated by a product supplier does not necessarily provide a balanced view. Also the date of last update and the credentials of the authors require judgement prior to use.

The principles documented by the Health on the Net Foundation (HON) state ‘that health-related websites must make clear the sources which they have used and ensure that the information presented is appropriate, independent and timely. As some sites may be sponsored by one party and hosted by a different one, these relationships should be clearly disclosed on the site’. The HONcode has been accredited to over 5500 sites and 1, 2 million web pages (http://www.hon.ch/med.html). The web site includes user guidance tools to guide in the review of health web sites.

A chronic disease self-management programme, for example the NHS expert patient programme, is facilitated by a lay leader and aims to enhance the self-efficacy to manage health (http://www.expertpatients.co.uk/course-participants/courses/expert-patients-programme). These, and other similar programmes, have a positive effect on participants’ self-efficacy, but disappointingly small effect on health outcomes, quality of life and healthcare use (Eysenbach et al. 2004; Foster et al. 2007). An alternative may be Internet-delivered health interventions. Although more research is needed on how such interventions work, who they work for and for what conditions, preliminary data suggest they can be effective under some conditions (Murray 2008b). Peer education harnesses the power of social norms by enabling people to spread health messages through their social networks (Campbell et al. 2008).

Coaching develops patients’ skills in preparing for a consultation, deliberating about options and implementing change (O’Connor et al. 2008). It may be provided face-to-face (FTF), or over the telephone, email or Internet. Health coaches are most commonly found in call centres, which improves access and coverage but usually lacks continuity or linkage with primary care practices. Linkage to care may make it easier to identify and tailor the coaching to the patients’ needs. Coaching needs to be tailored to individuals and integrated with existing health systems.

A systematic review assessed the evidence on implementing change. Motivational interviewing draws on people’s need for cognitive consistency. The combined effects of 72 trials of motivational interviewing in patients with various diseases showed no effect on glycated haemoglobin values, but significant positive effects were found for body mass index, total blood cholesterol and systolic blood pressure (Rubak et al. 2005). HIT applications for nascent use in motivational interviewing have only recently been initiated.

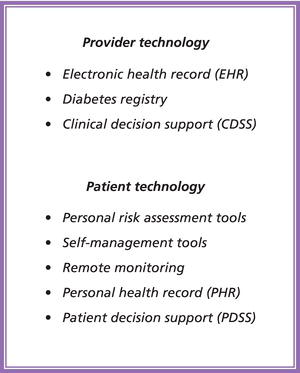

Figure 12.1 Overview of current health IT technologies used by healthcare providers or people with diabetes. Provider technologies represent comprehensive care applications in chronic care. Data are captured by professionals and information stored securely within the organisations. Patient applications support self-care management and enable diabetics to capture and review their own data, which may be shared with a third party over the Internet.

Less patient facing technology is in use today than HIT in healthcare organisations (Figure 12.1), but there appears to be a growing demand for remote patient monitoring to create quality care outcomes, ease of delivery and cost savings. Technology has been claimed to be a catalyst for change (Miller et al. 2009) and we may soon experience that a greater share of clinic visits today will be replaced by sophisticated technology encounters (personal eHealth ecosystems).

Although most of the applications available today for diabetes educators are supplied by their healthcare providers, there is much to be gained from contemporary systems and diabetes educators may utilise HIT to:

- Acquire health and patient information from trusted sources,

- Follow clinical indicators and health outcomes from diabetes registers,

- Network with peers for decision support,

- Track individuals with high risk,

- Monitor and interact with patients to support patient self-care, and

- Predict the individual need for follow-up visits and examinations (in the future).

Diabetes management tools

Electronic health records and shared care

Electronic health records (EHR) collect data from multiple sources and are used as the primary source of information at the point of care. Improved access to patient-specific information provides benefits for the safety and quality of diabetes care. A more comprehensive description of EHR as a system of hardware, software, policies and processes may be found in the literature (Shortliffe and Perreault 2000). EHRs support patient care and facilitate communication between the diabetes care team. In addition to this comprehensive care, diabetes registries and diabetes care management systems assist in a more limited scope of diabetes care.

Healthcare has been radically decentralised (Giddens 2007) with distributed patient data repositories. One of the greatest challenges facing HIT today is the effective sharing of information among healthcare providers. Today’s systems were designed primarily to facilitate administrative functions and a more open, standards-based HIT environment is required to capture, store, analyse and appropriately share information. Another barrier that needs to be amended is culture. Hospital care mirrors a knowledge-intensive service model with highly educated specialists and coordinated practice. These networks may be separated from primary care through organisational boundaries, but also to some degree by practice and identity that divide.

Resolutions to empower professionals in utilising HIT and to promote continuing development (Roberts 2009) have been set in motion (www.ukchip.org), but there are still restrictions to effective deployment, which is limited to connecting healthcare professionals and not patients. In the post-industrial society, we should be expecting empowered patients through a series of mechanisms, such as availability of information and personalisation of services and choice (Giddens 2007). HIT applications will emerge within a context of escalating citizens’ use of technologies.

Diabetes registers

Disease registers are databases that contain condition-specific information for a group of patients and may generate patient reports or aggregate information across the population. Registers can be simple databases that require manual data entry or integrated registers where the database is updated by data retrieval from EHRs or other patient information systems. Integrated registers track all patient cases with a given disease or health condition in the population. In addition, some disease registers are based on administrative register data.

Registers are most often used for monitoring disease status at a population level and to track progress of the disease using process and outcome measures. Action plans may be based on these results in order to slow down the disease progress (Calvert et al. 2009). Integrated registers also provide feedback to providers of care on overall performance by patient and by population. IT-enabled diabetes management has the potential to improve care processes, delay diabetes complications and save costs (Bu et al. 2007). Consequently, diabetes registers have been created for various purposes (Huen et al. 2000; Gudbjörnsdottir et al. 2003; Gorus et al. 2004; Carstensen et al. 2008).

In Scotland at Tayside (DARTS), one of the first diabetes registers was created on the recommendation of NHS that regional diabetes registers should be established in the UK to facilitate systematic, population-based monitoring of outcomes of diabetes and to ensure that diabetes care is effective, efficient and equitable (Morris et al. 1997). A national systematic approach since 2000 towards quality improvement of diabetes care included the creation of managed clinical networks and the Scottish Diabetes Survey reporting annual improvements in diabetes care (Morris 2006). This has led to a significant change in clinical practice providing a national platform to underpin clinical networks of diabetes care.

There are variations in inclusion criteria of the registers as well as in the clinical registration of patients into the health information systems (Rollason et al. 2009). Such issues are important for the quality of the register, and it is important to analyse the completeness of registration in the diabetes registers. By applying four criteria to identify diabetes patients from two metropolitan cities in Finland, we extracted from 2008 EHR data over 37 600 diabetic patients giving a diabetes prevalence of 4.6% (Harno et al. 2010). These data were applied to track metrics of the care process and service use in the diabetic population.

Analytic tools

In designing an IT-enabled chronic disease management programme, there is a wide array of options (Adler-Milstein and Linden 2009). Besides provider tools for diabetes care, some are designed for identifying and stratifying the population at risk. The predictive modelling software is an analytic tool that stratifies a population according to medical need and risk. The sophisticated predictive models rely on multiple regression and artificial intelligence to inform predictions. A predictive model that is able to draw on medical, pharmacy and lab data as well as clinical data is better positioned to make more accurate predictions. Predictive models support the stratification process and predict the members of a chronically ill population who are most likely to incur high medical service utilisation in the near future. They enable a programme to intervene and avoid associated costs.

Personal assessment tools, such as health risk assessments, are survey-based instruments that assess health history and current health factors to determine health status and risk. These tools are available online for individuals (http://star.duodecim.fi/star/healthcheck.do) or they can be applied to all adults without a diagnosis during primary care visits (Department of Health 2008). Health checks have been utilised also on data recorded in EHRs, but since the data contain little information on lifestyle factors (physical activity and diet) computer templates will be needed to allow capture. These tools typically include psychometrically validated questions (e.g. behavioural, clinical) and more sophisticated versions rely on branching logic and delivering automated feedback based on responses.

Personal health tools and self-care

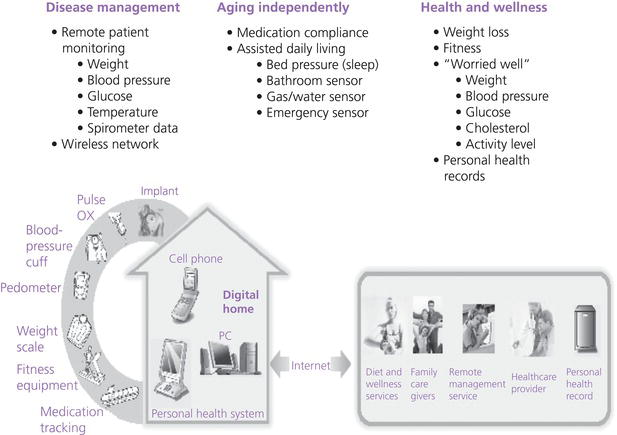

We may foresee people with diabetes who that are supported by personal health tools that engineer awareness and motivation and augment patients’ power to take decisions and be proactive in taking responsibility for their health (Figure 12.2). The present tools, although less sophisticated, nevertheless help in guiding diabetics interactively to manage their health.

Figure 12.2 The Continua Alliance has designed the guidelines towards the establishment of a personal eHealth ecosystem. These guidelines address the technical barriers and interoperability amongst different vendors allowing the transfer of data from self-management tools in this ecosystem. The diabetics that are supported by personal health tools engineer awareness and motivation, augment patients’ power to take decisions and be proactive in taking responsibility for their health (www.continualliance.org).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree