CHAPTER 27 Taenia Solium and Neurocysticercosis

Neurocysticercosis at a Glance

Introduction

Prior to 1980, cysticercosis was regarded as a fairly rare disease found in endemic areas. Subsequent advances in neuroimaging and serological assays are facilitating the diagnosis of patients with both cysticercosis and taeniasis. Neurocysticercosis is now recognized as a critical public health problem in endemic countries and among immigrants from resource-limited countries.1–3

Epidemiology

Neurocysticercosis is endemic in areas where pigs are raised under conditions that allow them access to human fecal material.3 In these endemic areas, the majority of pig rearing is done on small farms. The pigs are generally not penned and are allowed to forage freely, enabling even small farms to raise animals without the expense of having to feed them. Meat inspection, improved sanitation, and improved animal husbandry led to the eradication of cysticercosis in Western Europe (an area highly endemic as late as the nineteenth century). However, these approaches have generally failed in developing countries. Currently, porcine cysticercosis remains widespread throughout Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, South and Southeast Asia, as well as parts of Korea, China, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea. In these areas, human tapeworms and cysticercosis are common. There are few good data upon which to base estimates of global prevalence or burden of disease. Around 2.5 million people worldwide are thought to carry the pork tapeworm. The estimated prevalence of neurocysticercosis ranges from 20 to 100 million cases with 50 000 deaths each year attributed to the infection. Case series employing neuroimaging studies find neurocysticercosis in 20–50% of adults with seizures and a similar portion of patients with chronic epilepsy.

In the United States, neurocysticercosis is primarily a disease of immigrants. It was rarely diagnosed prior to 1980. The numbers of cases, however, had increased fourfold by the early 1980s. An investigation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concluded that most of the increase was attributable to improved diagnosis due to the introduction and increased use of computed tomography (CT) scanning.4 In the 1980s and 1990s, large case series were reported from California, Colorado, Texas, New York, and Chicago. The vast majority of cases were diagnosed in Hispanic immigrants, mainly from Mexico and Central America. However, cases were also seen among immigrants from Asia (especially India, Korea, and Southeast Asia), and, less frequently, Africa. These proportions are similar to the percentage of the foreign-born population from those areas. Most case series also include US-born cases, most associated with travel to endemic areas. However, there have been over 70 welldocumented cases of local transmission in the US. Most of these cases can be tied to tapeworm carriers. For example, four Orthodox Jews in New York City were documented to have neurocysticercosis.5

More recently, prospective and population-based studies have been applied to the epidemiology of neurocysticercosis in the US. After neurocysticercosis was made a reportable disease in California it was noted that among the first 138 cases, 19 were US born, but only 10 did not report travel outside of the US.6 A study of family contacts identified tapeworm carriers among the contacts of US-born cases. Among 57 cases seen in Oregon, 72% were born in Mexico and 5% in Guatemala, but 18% were born in the US, some of whom denied travel to endemic areas.7 In patients presenting with seizures to emergency rooms, neurocysticercosis was felt to be the cause in 38/1801 (2.1%) patients, and 13.5% among Hispanics.8 All of the cases in which information was available were either born in or traveled to an endemic region and most were Hispanic or immigrants. In a series from Houston, Texas,9 most of the cases were immigrants, primarily from Central Mexico or Central America. Among six US-born cases, all had traveled frequently to villages in Latin America. Again, 2% of all seizures and 16% of seizures among Hispanics were thought to be due to neurocysticercosis.

Sorvillo and colleagues reviewed death certificates from California from 1988 until 2000.10 Of the 124 deaths attributed to neurocysticercosis most were among Hispanics (115/124), primarily immigrants from Mexico. In a survey of seroprevalence of cysticercosis and taeniasis,11 the seroprevalence for antibody to the tapeworm stage was 1.7%, but none of the children was seropostive.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

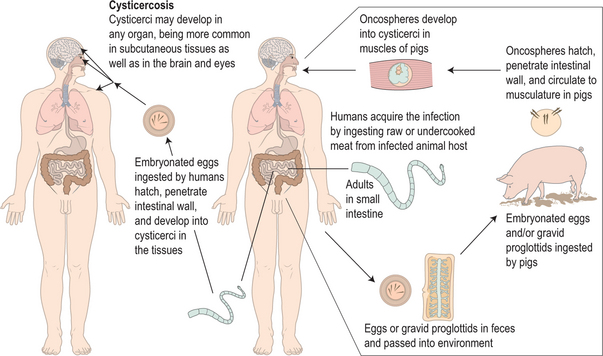

Taenia solium, the pork tapeworm, is a cestode parasite that causes two different and highly distinct forms of infection in the human host. Taeniasis (or taeniosis) refers to infestation of the intestinal tract by the adult tapeworm (Fig. 27.1). The term cysticercosis refers to infection of tissues such as muscle and brain with the larval cysticercus form. The term neurocysticercosis refers to cysticercosis involving the central nervous system (CNS) (including the subarachnoid space, spinal cord, and eyes).

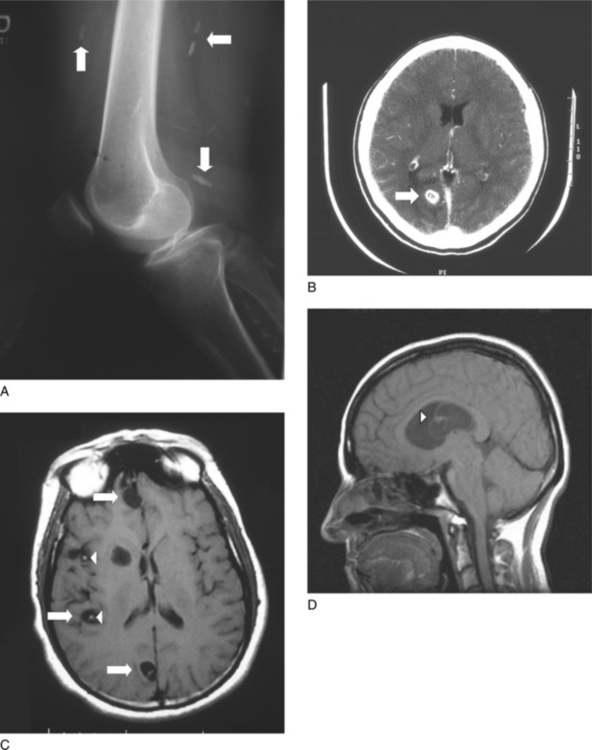

Fig. 27.1 The life cycle of Taenia solium.

(Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention DPDx.)

Humans are the definitive hosts of T. solium, harboring the adult tapeworm in the intestines. The tapeworms reach lengths of several meters. The worm sheds eggs and/or gravid proglottids intermittently into the feces. In areas where pigs have access to the infected human waste, foraging pigs ingest the eggs or proglottids. Once ingested, the eggs hatch to release the larval oncospheres, which attach to and penetrate the wall of the gut. The larvae enter the bloodstream and migrate to the tissues, where they develop into cysticerci over a period of a few weeks. The cysticerci have an invaginated scolex (poised to develop into a tapeworm when ingested), a bladder wall, and cyst fluid (which contains a mixture of parasite and host material). They actively suppress the host inflammatory response and are able to survive in the porcine tissues for periods of a few years. When infected pork is eaten, the scolex evaginates, attaches to the intestinal wall, and develops segments termed proglottids. The proglottids mature as they are displaced from the scolex by newer proglottids. As they mature, they develop testes and ovaries that form eggs. The mature, gravid proglottids and eggs are shed intermittently. The eggs are not only shed into the environment, but also contaminate the hand and fingernails of the tapeworm carriers. These eggs can then autoinfect the tapeworm carrier or other people in close contact with the carrier. Thus, human cysticercosis requires no contact with pigs or pork, as illustrated by cases described in vegetarians in India and orthodox Jews in the United States. When these eggs are ingested by humans they hatch and release the enclosed larvae, called oncospheres, which migrate through the blood and develop into cysticerci in a wide range of tissues. In most tissues, the cysticerci cause few symptoms and their survival is limited. By contrast, infection of the central nervous system often lasts for years and can cause severe symptoms.

Cysticerci reach their mature size within a few weeks of infection. However, studies of British subjects who developed neurocysticercosis after working in India, and of US immigrants, reveal that there is typically an incubation period of several years between infection and clinical presentation.9 Laboratory studies have identified a complex array of parasite molecules that suppress the host inflammatory response.12 Thus, the quiescent phase is thought to result from the parasite’s ability to evade the host immune system. Over time, the cysticerci age and lose the ability to evade immune attack. A brisk cell-mediated response ensues, during which the cysticerci are surrounded by and infiltrated with a granulomatous reaction composed primarily of mononuclear cells, with variable numbers of eosinophils and neutrophils. In an animal model, the granulomatous host response to the degenerating cysts rather than the parasite per se produces seizure activity, the characteristic clinical presentation of parenchymal neurocysticercosis. Over a period of months, the inflamed parasite passes through a series of stages of inflammation until it either resolves radiographically or is replaced by a small calcified granuloma (which appears as a small nodule on imaging studies). If the lesions resolve, seizure activity usually also resolves. Persistent seizure activity has been associated with the presence of calcifications. While the pathophysiology is not clear, periodic release of persistent parasitic antigen from the calcification is thought to lead to recurrent seizures.

The pathogenesis of extra-parenchymal neurocysticercosis is somewhat different.12 Cysticerci in the cerebral ventricles often cause obstructive hydrocephalus. Pathologic studies show that most of these cysticerci are viable. Thus, the obstructive hydrocephalus is thought to result from mechanical obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow by the cysticerci. Cysticerci in the subarachnoid space are often accompanied by an inflammatory response. In this case, the inflammation may lead to meningeal inflammation (with headache and nuchal rigidity) and chronic arachnoiditis. The latter may cause vasculitis and strokes or communicating hydrocephalus. Occasionally, cysticerci in the subarachnoid space may enlarge and cause mass effect. In patients with multiple cysticerci, several forms of the disease can be present at the same time.

Clinical Manifestations

T. solium can cause a wide range of clinical manifestations depending on the form of the parasite involved, the number of parasites, the location, and the degree of host inflammation.1–3

Cysticercosis

Cysticerci have been observed in a wide range of tissues including all groups of skeletal muscles as well as in the myocardium. Cysticerci in muscle are usually asymptomatic; however, massive infection may result in weakness and/or pseudo-hypertrophy. In muscle, the cysticerci form elongated structures parallel to the muscle fibers. In most cases, the cysticerci progress to calcified granulomas without causing significant symptoms. Thus, muscle involvement is typically identified via cigar-shaped calcifications found as an incidental finding on X-rays (Fig. 27.2A).

Neurocysticercosis

Parenchymal neurocysticercosis

The most common presentation of neurocysticercosis in the United States is that of a solitary degenerating parenchymal lesion (Fig. 27.2B). These patients tend to present with new-onset seizures or headaches. Neurocysticercosis patients are less likely to report generalized seizures than other seizure patients. The seizures are typically focal with secondary generalization. However, they are often initially described as generalized.

Patients from endemic areas may also present with multiple parenchymal lesions (Fig. 27.2C). In such cases, seizure activity is also the most common presenting symptom.

Extra-parenchymal neurocysticercosis

Extra-parenchymal neurocysticercosis includes cysts within the ventricles of the brain (either freely floating or attached to the ventricular wall) (Fig. 27.2D), in the subarachnoid space, in the eye, or in the spine. The presentation of extra-parenchymal disease varies depending on the location of the cysts.

Ventricular cysticercosis characteristically presents with increased intracranial pressure from obstructive hydrocephalus. Headache, nausea, papilledema and altered level of consciousness can all be seen. The onset is quite variable and may range from mild intermittent headaches to sudden loss of consciousness. In some cases, symptoms may vary with head position from ball-valve effects of the parasites.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree