Systematic Pain Assessment

A comprehensive and rational strategy for cancer pain assessment begins with data collection and terminates with a correct and clinically relevant diagnosis. This outcome requires a thorough evaluation of the multiple factors that contribute to the complaint of pain. Certainly, this evaluation involves discovery of the etiology of the pain and predicting its future evolution. Each of the sites from which pain originates may have a different mechanism and prognosis and treatment strategy. Pain is likely to affect sleep, functional capability, activity level, and psychological well-being; all must be considered. Another key factor is the impact of the cancer itself on the patient. A comprehensive evaluation will allow the clinician to evaluate possible therapeutic interventions and establish long-term goals with the collaboration of the patient and the patient’s family.

Table 12.1 describes the goals of a comprehensive painrelated history. Such goals must be specified and the pain syndrome and its underlying mechanisms evaluated in a comprehensive assessment.

COMPONENTS OF PAIN HISTORY

Table 12.2 itemizes the essential components of the assessment of the pain complaint in a patient with cancer.

Location

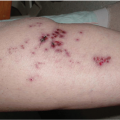

Multiple pains at different sites characterize many patients with advanced disease. This is particularly true in patients with breast, lung, and prostate cancer, compared with those harboring gastrointestinal cancers.1 A tumor usually produces pain in the region in which it is growing. Somatic pain from bone metastases is usually well localized. However, a tumor involving viscera tends to produce diffuse pain and is often referred to remote regions, based upon the embryologic developmental patterns. Neuropathic pain is typically in the sensory distribution of a nerve or nerve root. For example, prostate cancer may initially present with localized pelvic pain, because of localized tumor growth within the prostate or adjacent organs such as the bladder. With tumor progression, infiltration of the adjacent lumbosacral plexus can produce radicular lower extremity symptoms suggestive of neuropathic pain. Remote metastasis to bone can produce localized somatic pain. The location of pain is obviously the first step in its characterization and often determines subsequent diagnostic investigations.

TABLE 12.1 USES OF THE PATIENT’S HISTORY | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Intensity

The published guidelines promulgated by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research,2 the American Pain Society,3 and the American Society of Anesthesiologists4 all have advocated the routine use of pain rating scales. Rating scales are particularly important when initiating therapy for pain or when changing treatment regimens. All of these guidelines suggest that clinicians teach patients and families to use assessment tools at home so that consistency of pain management can be established and maintained. Standard pain intensity assessment tools for determining the intensity of pain are discussed in Chapter 6, “Characteristics of Cancer Pain.”

Quality

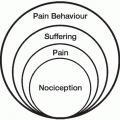

The descriptors utilized by patients can be helpful in identifying the origin of the pain. Cancer can be nociceptive (somatic or visceral structures) or neuropathic. Patients tend to describe pain that is neuropathic in origin as burning, shock-like, or shooting in quality, whereas they often describe pain originating from somatic structures as aching, nagging, throbbing, or sharp. Pain qualities are the cornerstone of the McGill Pain Questionnaire and often permit diagnosis by themselves.

TABLE 12.2 ASPECTS OF PAIN COMPLAINT | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Timing and Duration

Pain intensity may fluctuate with time of day or activities. The first criterion is whether the pain is constant or intermittent. Constant pain is present continuously but usually varies in intensity. Intermittent pain implies that pain is present for definite periods of time and absent between episodes. One type of intermittent pain is breakthrough pain: a sudden and brief flare of pain associated with activity or change of position occurring in a patient who has chronic pain and is receiving opioids. It is essential that patients and their caregivers understand the concept of breakthrough pain and its management. Breakthrough pain is discussed in Chapter 6, “Patterns of Cancer Pain.”

Acute and chronic pains have traditionally been distinguished solely by the duration of the complaint. This distinction may have some validity for short-term complaints but does not take into account the multidimensional nature of chronic pain. Von Korff and Dunn5 compared duration-based and prospective approaches to defining chronic pain in terms of their ability to predict future pain course and outcomes for primary care patients with chronic pain and determined that long-term pain outcomes were highly variable and uncertain, with less dependence on pain duration alone. Chronic pain always leads to changes in the nervous system that may not be present in acute pain; this, rather than duration alone, is probably the discriminating factor that separates acute from chronic pain.

Modulating Factors

Knowledge of the issues that make pain worse or better helps clinicians to design an appropriate pain treatment plan. Activities, position changes, or eating, for example, may produce pain increases in a wide array of cancers. Patients with metastatic disease to weight-bearing bones may report more pain when they stand or sit. Breast cancer metastatic to the axillary nodes may produce severe pain with abduction of the upper extremity during positioning for external beam radiation therapy. Recognition of such positional and activity-related changes in pain levels is required for the implementation of optimal pain management.

Responses to Previous Analgesic and Disease-Modifying Therapies

Past history and, in particular, past exposure to medications must be ascertained. Understanding of previous opioid use and its benefits or side effects is essential for treatment planning. Side effects with a particular opioid may limit successful future titration with the same opioid. This is also true for other medications commonly used for pain and symptom management. A positive response to chemotherapy or radiation therapy with decrease in tumor bulk may alleviate pain. The recurrence of pain at a later date mandates reevaluation for the possibility of tumor recurrence.

Pain Impact

Information about changes in activities of daily living, such as work and recreational activities, mood, appetite, mobility, sleep patterns, and sexual functioning, must be part of pain assessment. Symptom checklists and quality of life measures are useful in this evaluation. A discussion of some of the instruments we routinely use for the assessment of pain impact and other variables follows.

Pain intensity, pain relief, and mood are assessed by the Memorial Pain Assessment Card (MPAC), a brief, validated measure that uses visual analog scale (VAS) scores. It also contains a mood scale that has been correlated with other measures of global psychological distress, depression, and anxiety. It is considered to be a very useful but brief measure of global symptom distress. The MPAC does not provide detailed descriptors of pain, but its brevity and simplicity facilitate the collection of essential data while minimizing patient burden. Compliance is definitely enhanced when the assessment tool is less cumbersome.

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) measures both the pain intensity (sensory dimension) and pain interference in the life of the patient (reactive dimension). Pain relief, pain quality, and patient perception of the cause of pain are also assessed. Pain in general, at its worst, at its least, and right now are determined via numerical scales. A pain diagram is used to localize the regions of pain. Interference with daily functions, mood, and enjoyment of life are also quantified. This questionnaire is self-administered, easy to understand, and available in many languages. The BPI has been validated in many languages, including Chinese, Filipino, French, Hindi, Italian, Spanish, Greek, Turkish, and Vietnamese, and has been shown to produce similar data from patients in these countries and from many different cultures. BPI has several applications, including studies of the epidemiology of cancer pain, the routine clinical assessment of pain, efforts to assure the quality of pain management, and the conduct of clinical trials examining the effectiveness of cancer pain treatments.

Pain and the Activities of Daily Living

Mild pain may not impair function or distract some patients.6 However, as severity of pain increases, a threshold may be crossed; the pain can no longer be ignored. Now the pain disrupts the patient’s life. Constant, daily pain usually adversely impacts activities of daily living. As pain increases over time, restriction in activity occurs and depression is likely to ensue.7 We strongly believe that indicators of physical, psychological, and social functional status must be included in the comprehensive assessment of functioning. These include interference with general activities, mood, walking, ability to work, relations with others, and sleep. A reliable, valid and brief measure of pain-related disability, The Pain Disability Index (PDI), was developed as a self-report measure of general and domain-specific, pain-related disability8 (Appendix A).

Many factors in addition to pain intensity play a role in disability.9 Pain site, patient age, how much of the time pain is experienced, use of pain medication, and the number of pain locations have all been found to be associated with disability.10 The Pain Disability Questionnaire (PDQ) is designed to evaluate chronic disabling musculoskeletal

disorders (Appendix L). Patients are scored on total functional disability from 0 (optimal function) to 150 (total disability). The focus, like other health inventories, is primarily on disability and activities of daily living. However, unlike most other measures, this instrument is designed for the full array of chronic disabling painful musculoskeletal disorders, including upper extremity and lower extremity disorders, rather than just low back pain, or spinal disorders. In addition, psychosocial variables also form a core in the PDQ. Gatchel et al.11 reported on the validity of the PDQ in patients with chronic disabling musculoskeletal disorders.

disorders (Appendix L). Patients are scored on total functional disability from 0 (optimal function) to 150 (total disability). The focus, like other health inventories, is primarily on disability and activities of daily living. However, unlike most other measures, this instrument is designed for the full array of chronic disabling painful musculoskeletal disorders, including upper extremity and lower extremity disorders, rather than just low back pain, or spinal disorders. In addition, psychosocial variables also form a core in the PDQ. Gatchel et al.11 reported on the validity of the PDQ in patients with chronic disabling musculoskeletal disorders.

Maltoni et al.12 identified selected clinical parameters as prognostic indicators for terminal cancer patients, including clinical experiences, physical capabilities, and clinical symptoms both relating to and unrelated to nutritional state. We believe that Performance Status Tables are useful adjuncts to the assessment of physical activity levels (see Table 8.3 and Table 12.3). It must be recognized, however, that the palliative treatment of advanced cancer and the terminally ill is based upon a concept of well-being that extends beyond physical functioning alone.13

Psychological State

Assessment of the cancer patient must reflect awareness of the many relevant psychological factors. Distress in the cancer patient is modulated by psychological factors such as personality, coping skills, past experiences, and environmental interactions. Knowing that the patient has received outpatient or inpatient psychiatric care in the past helps to clarify psychological risks. Information on how the patient handled previous stressful or painful events may provide insight into whether the patient is likely to manifest chronic illness behaviors. Past experiences as well as anticipated consequences influence the present psychological state and must be considered in formulating a diagnosis and plan for management.

Familial and Professional Function

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree