Symptom-Directed Pain Management: Medication

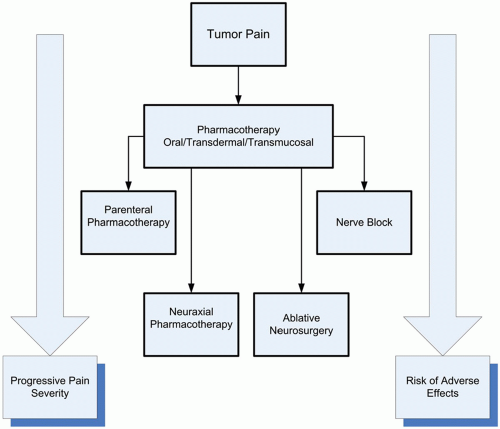

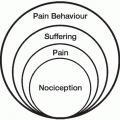

Interdisciplinary collaboration is the cornerstone of management of the cancer patient with pain. It is essential that the managing clinicians understand the cause or causes of pain and direct treatment appropriately and not simply treat the pain as an isolated symptom. Successful management strategies usually require a team approach, focusing not only on the nociceptive processes but also on the many other factors that influence the perception of pain. All options of pain management, which includes source modification, alteration of pain perception, and interruption of nociceptive transmission, should be considered continuously throughout the course of treatment. For example, it is not unusual to manage patients initially with pharmacologic options and then to consider focused therapy as isolated problems emerge (eg, neurolytic intercostal nerve block for an isolated rib metastasis). Figure 16.1 outlines tumor pain management strategies directed at the treatment of nociceptive and neuropathic pain at our institution. It is important to remember that eradication of the tumor with surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy are omitted from this illustration but should be factored into management strategies. Treatment options are highly individualized and multiple therapies may be required in the same patient. It is not unusual to continue oral pharmacotherapy in patients receiving neuraxial infusions. In addition, nerve blocks may be considered at any time during treatment. It is also important that the algorithm applies to tumor-related pain only. Different strategies are required for the management of treatment-related and unrelated (usually chronic) pain problems.

Pharmacologic strategies for the control of tumor pain are listed in Table 16.1. The rapidity of response is determined by the urgency for pain control. Patients with severe, unremitting tumor pain may require admission to hospital for additional imaging to determine the source of pain and for parenteral opioid therapy, neuraxial therapy, or both.1 Patients with less-rapidly progressive pain can usually be treated on an outpatient basis. Most patients

will respond satisfactorily to relatively simple oral pharmacotherapeutic strategies. Strategies should follow the principles endorsed in the World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder (see “World Health Organization Recommendations for Pain Relief and Analgesic Ladder”). Unless the acuity of the clinical situation requires it, analgesics should be optimized (maximum effective doses or to the appearance of intolerable dose-limiting side effects) before considering more specialized (and usually invasive) approaches. The exception to this rule is that relatively simple ablative (chemical or thermal) procedures such as celiac and superior hypogastric plexus blocks, neurolytic subarachnoid and intercostal blocks, and selected peripheral nerve blocks or tumor ablation may be considered as an adjunct. The intent of these procedures is not to replace medication management, but rather to supplement it.

will respond satisfactorily to relatively simple oral pharmacotherapeutic strategies. Strategies should follow the principles endorsed in the World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder (see “World Health Organization Recommendations for Pain Relief and Analgesic Ladder”). Unless the acuity of the clinical situation requires it, analgesics should be optimized (maximum effective doses or to the appearance of intolerable dose-limiting side effects) before considering more specialized (and usually invasive) approaches. The exception to this rule is that relatively simple ablative (chemical or thermal) procedures such as celiac and superior hypogastric plexus blocks, neurolytic subarachnoid and intercostal blocks, and selected peripheral nerve blocks or tumor ablation may be considered as an adjunct. The intent of these procedures is not to replace medication management, but rather to supplement it.

TABLE 16.1 PHARMACOLOGIC STRATEGIES FOR THE CONTROL OF TUMOR PAIN | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Complex interventional pain procedures may be considered for severe, uncontrolled pain, if intractable side effects occur, if patients prove refractory to conventional medication therapy, and if rapid pain control is required. These procedures include epidural analgesia and/or parenteral opioid therapy (usually intravenous or subcutaneous administration). As many of these patients have high systemic opioid requirements, it is not unusual to combine epidural and parenteral therapies. A small percentage of patients may fail even these therapies and should then be treated with intrathecal drugs, cordotomy, or myelotomy.

Some patients will have pain refractory to all the above modalities. For these patients adequate relief may only come at the cost of sedation. Controlled sedation can be accomplished through the use of benzodiazepines,2 neuroleptics, barbiturates, and (for hospitalized patients) propofol.3 The ethical acceptability of sedation at the end of life depends upon informed consent and an acknowledgment of the “principle of double effect,” which distinguishes between the compelling primary therapeutic intent (to relieve suffering) and unavoidable, untoward consequences. Palliative sedation is distinct from euthanasia because the intent is relief from suffering without death as a required outcome.4 In most studies on the use of palliative sedation, the period of time between the start of sedation and death is consistently in the range of 24 to 72 hours.5, 6, 7, 8 In one study assessing the need and effectiveness of sedation in dying patients with intractable symptoms, patients who were sedated had a longer survival when compared with patients who were not sedated.9

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PAIN RELIEF AND ANALGESIC LADDER

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, uncontrolled cancer pain was recognized as a serious health problem.10, 11, 12, 13 In 1986, WHO, a specialized agency of the United Nations with primary responsibility for international health matters and public health, published a monograph with the title Cancer Pain Relief that aimed to improve the management of cancer pain.14 These guidelines arose from evidence of poor management of cancer pain in both the developing and the developed countries. At the time of this publication, WHO recognized that there was a lack of availability of drugs essential for the relief of cancer pain in many areas of the world. In addition, many health professionals, institutions, and governments were reluctant to use “strong” opioids because of fears of addiction and tolerance among patients, and the potential for illegal use in the wider community. Initial field testing of the WHO recommendations was encouraging.15 This monograph has been translated into 22 languages and more than one half million copies have been sold. The WHO revised its monograph in 1990 and 1996.16, 17 We believe these three publications have been pivotal in revolutionizing cancer pain management worldwide and that they merit detailed discussion. Although the drugs recommended may have become somewhat obsolete over time, the principles of use of these classes of drugs are very important for the reader to understand and implement.

In the initial monograph, WHO emphasized the importance of a systematic approach to cancer pain assessment and management. The essence of pain management was that analgesic drugs were the mainstay in managing cancer pain. The WHO method can be applied anywhere as long as basic drugs and adequately-trained health care professionals are available. The principal contribution of this publication was a relatively simple three-step analgesic ladder approach to pain management that was based on a small number of relatively inexpensive drugs. This approach is based on the premise that health care professionals should learn how to use a few drugs well. Although the ladder is considered key to management, WHO acknowledged that not all pain complaints were equally responsive to analgesics and that alternatives such as neurolytic and neurosurgical procedures may be necessary as a supplementary approach in a small number of patients. In addition, treatments such as palliative radiation therapy may also be of considerable benefit. The first approach to care should also include anticancer treatments, if available and if appropriate. Symptomatic treatment measures should be used concurrently. These measures include drug therapy, physical therapy, and psychological approaches. Temporary local anesthetic blocks, such as trigger-point injections and regional anesthesia, should be considered if available. If pain was not adequately controlled, a “strong” opioid should be used in combination with a nonopioid analgesic and adjuvants, if necessary. When pain was localized to a dermatome or was unilateral, neurolytic and neurosurgical procedures should be considered.

In 1986, the three standard analgesics were aspirin, codeine, and morphine. Alternatives could be substituted

as necessary (Table 16.2). In the first version of the ladder, Step 1 specifies a nonopioid for mild pain. Suggested doses of aspirin were 250 to 1000 mg every 4 to 6 hrs with a daily maximum dose of 4 g/day. Step 2 added a “weak” opioid such as codeine for moderate pain to the nonopioid. Use of the nonopioid was required in this step and adjuvant use was optional. Suggested doses of codeine were 30 to 130 mg with 500 mg of acetaminophen or 250 to 500 mg of aspirin every 4 to 6 hours. Step 3 required a “strong” opioid such as morphine to control severe cancer pain, with the option of using a nonopioid or an adjuvant drug if needed.

as necessary (Table 16.2). In the first version of the ladder, Step 1 specifies a nonopioid for mild pain. Suggested doses of aspirin were 250 to 1000 mg every 4 to 6 hrs with a daily maximum dose of 4 g/day. Step 2 added a “weak” opioid such as codeine for moderate pain to the nonopioid. Use of the nonopioid was required in this step and adjuvant use was optional. Suggested doses of codeine were 30 to 130 mg with 500 mg of acetaminophen or 250 to 500 mg of aspirin every 4 to 6 hours. Step 3 required a “strong” opioid such as morphine to control severe cancer pain, with the option of using a nonopioid or an adjuvant drug if needed.

TABLE 16.2 BASIC DRUG LIST FOR WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION ANALGESIC LADDER, 1986 |

|---|