Surgical Technique

Charles S. Coffey

Terry A. Day

The location and behavior of oral cavity (OC) cancers make surgery the treatment of choice in the majority of cases. Many lesions can be accessed transorally without major perturbation of the surrounding uninvolved structures, resulting in improved cosmesis and satisfactory preservation of functions such as speech, chewing, and deglutition. Radiation therapy, although effective in the treatment of other head and neck sites, is hindered by the bony structures of the OC, air-tissue interfaces, and involuntary mobility of the tongue and the floor of mouth (FOM). Additionally, oral squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), minor salivary gland tumors, and sarcomas are associated with a more limited response to nonsurgical treatment. The methods of surgical approach to the OC are discussed below.

TRANSORAL/PERORAL APPROACH

Many tumors of the OC are readily accessible for excision via a transoral approach, without the need for external incisions, or extensive dissection to achieve adequate exposure. This is particularly true for many early-stage (T1 or T2) lesions of the lip, the buccal mucosa, the anterior tongue, the FOM, or the alveolus. Transoral exposure may be maximized by use of a variety of devices, including circumferential cheek retractors, dental bite blocks, self-retaining mouth gags, or various handheld retractors for the tongue and the buccal mucosa. Exposure, access, and safety are improved when nasotracheal intubation is employed, permitting access without hindrance by the endotracheal tube in the OC. When monopolar electrocautery is employed, guarded cautery tips and coated or nonferrous retractors should be used to minimize the risk of injury to the lips and the oral commissure. Heavy suture, tongue retractors, or a penetrating clamp may be used to retract the tongue and provide additional exposure to the posterolateral tongue and the FOM. When limited transoral resection is combined with surgical management of the neck, care should be taken to avoid communication of the oral and the neck wounds when possible to minimize the risk of fistula formation. However, such concerns must always be secondary to oncologic considerations and achieving the exposure necessary for appropriate tumor extirpation. When tumors of the OC extend into the oropharynx, additional technology can afford improved visualization with transoral robotic surgery using three-dimensional visualization and robotic instruments. Transoral laser surgery has also been recommended for tumors of the OC and the oropharynx. When the transoral approach is employed, a separate neck incision and neck dissection is performed, avoiding entry into the OC whenever possible.

COMBINED TRANSORAL/TRANSCERVICAL APPROACHES TO THE ORAL CAVITY

Achieving adequate exposure of large (T3 or T4) or deeply invasive lesions of the anterior OC may not be possible via a strictly transoral approach. In combination with surgical management of the neck, variations of either the mandibular lingual release or the “visor” approach allow excellent access to the OC through exposure via the neck.1,2 In most cases, an upper neck dissection is performed prior to the combined approach to allow exposure of the external carotid branches, the lingual and the hypoglossal nerves, and the suprahyoid muscles.

A broad horizontal incision in a cervical skin crease is initially performed. An apron flap that is elevated to the inferior border of the mandible can be utilized in a unilateral fashion for the mandible/OC or bilaterally when large defects, anterior FOM/mandible, and bilateral tumors are treated. The unilateral approach is usually intended for lateral mandibular body, retromolar trigone, lateral FOM, or lateral tongue defects. An important consideration when elevating the subplatysmal flaps superiorly to and beyond the inferior border of the mandible is elevation and mobilization, with preservation of the marginal mandibular nerve. Ipsilateral or bilateral nodal contents are removed at this time, if indicated.

Lingual Release

Lingual release refers to the separation of the lingual aspect of the mucosal surfaces from the inner aspect of the mandible 270° from the glossotonsillar sulcus on one side, anteriorly around the mandible to the contralateral glossotonsillar sulcus.1 Although commonly bilateral, unilateral release is appropriate and feasible in certain small tongue or FOM cancers. In most cases, an upper neck dissection is performed prior to the combined approach to allow exposure of the external carotid branches, the lingual and the hypoglossal nerves, and the suprahyoid muscles.

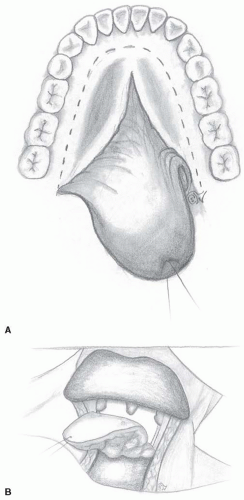

Once the soft tissue and muscular attachments to the mandible are released, the entire tongue and the FOM is “released” and can readily fall into the neck and be visualized and dissected via the neck incisions, rather than transorally. If mandibular resection is not planned, mandibular lingual release may be performed without dissection of the soft tissue envelope overlying the mandible (Fig. 16-38A,B). The digastric, the mylohyoid, the geniohyoid, and the genioglossus muscles are released at their anterior attachments, and subperiosteal dissection is performed along the inner cortex of the mandible. The intraoral mucosa is released at the dental mucosal junction with preservation of the interdental papillae in the dentate patient, or along the superior alveolar crest in the edentulous patient. Following mucosal release, the tongue and the FOM are delivered into the neck. If additional posterior exposure of the base of the tongue or the lateral pharynx is required, the dissection may be extended into a pharyngotomy incision.

Visor Flap for Mandibulectomy and Plating

The term “visor” is used to differentiate it from an “apron” flap, whereby visor is a bilateral neck and cheek flap elevated cephalad beyond the mandible to expose the body of the mandible bilaterally. Thus, the flap of skin can be considered a visor that nears the upper cheek and eyes. The apron flap, however, is limited in its superior extent, and thus does not reach the level of the cheek but forms an apron over the neck region. In most cases, an upper neck dissection is performed prior to the combined approach to allow exposure of the external carotid branches, the lingual and the hypoglossal nerves, and the suprahyoid muscles.

If mandibular resection is planned, a visor flap is created by subplatysmal dissection extended superiorly over the lateral surface of the mandible. This may, although not frequently, require division of bilateral mental nerves, and patients must be counseled preoperatively regarding the resulting sensory deficit. If the mandible does not require resection on one side, the mental nerve is preserved. As opposed to the “lingual” release where the incision is in the gingival or lingual aspect of the mandible, the “mandibular” release requires a releasing incision along the gingivolabial and gingivobuccal sulcus. When there is no periosteal involvement or tumor growth through the outer cortex of the mandible, the transosseous plate can be placed prior to osteotomy and removed. This may preserve occlusion and cosmesis of the mandibular contour and height. Otherwise, intermaxillary fixation may be necessary to maintain mandibular position for reconstruction. Once appropriate releasing incisions are completed, the mandible, the tongue, and the FOM are delivered into the neck. Tumor is resected with osteotomies in the bone where indicated, and margins are taken peripherally, deep, and in the neurovascular bundle and marrow of the mandible. Particular attention is paid to preservation of the lingual and the hypoglossal nerves when allowable. For large tumors of the tongue, exposure, mobilization, and ligation of the ipsilateral lingual artery in the neck prior to resection may aid hemostasis, and mobilization of the hypoglossal nerve can allow preservation of some branches when oncologically safe. Following resection, the surgical defect is appropriately reconstructed, with particular attention paid to restoring a soft tissue barrier between the OC and the neck. Native FOM musculature or myofascial tissue from the reconstruction flap should be firmly affixed to the mandible, via holes drilled into the bone, if necessary. Additional considerations would include laryngeal and/or hyoid suspension to improve postoperative swallowing function.

Mandibular Swing Approach

The mandibular swing approach refers to a parasymphyseal or midline osteotomy and lip split, which allows the mandible and lip/cheek complex to “swing” laterally, leaving a wide open access to the OC, the retromolar trigone, the deep tongue, the oropharynx, and the parapharyngeal space without limitation by position of the lips, the cheek, or the mandible (Fig. 16-39). Such an approach may also provide access to the upper oropharynx for oral tumors extending into the soft palate, the tonsillar fossa, the glossopharyngeal sulcus, or the base of tongue. A variety of incisions for dividing the lower lip and the chin have been described, including straight line, zigzag, and chin button among others.3,4 A visible facial scar is unavoidable, but patients who

have been appropriately counseled are generally not dissatisfied with the postoperative appearance.5 The most aesthetically and functionally acceptable incisions permit precise reapproximation of the vermilion and the orbicularis muscle layer and include techniques to disrupt the linear scar and minimize contracture6 (Fig. 16-40). The lip incision is extended along the mental crease into the neck, where it is joined to the cervical incision to allow broad surgical access. Neck dissection is generally performed at this time, not only for oncologic purposes (if indicated), but also to maximize exposure of the FOM and the posterior OC. In most cases, an upper neck dissection is performed prior to the combined approach to allow exposure of the external carotid branches, the lingual and the hypoglossal nerves, and the suprahyoid muscles. If oropharyngeal exposure is required, this may also be optimized by dissection of the lateral neck.

have been appropriately counseled are generally not dissatisfied with the postoperative appearance.5 The most aesthetically and functionally acceptable incisions permit precise reapproximation of the vermilion and the orbicularis muscle layer and include techniques to disrupt the linear scar and minimize contracture6 (Fig. 16-40). The lip incision is extended along the mental crease into the neck, where it is joined to the cervical incision to allow broad surgical access. Neck dissection is generally performed at this time, not only for oncologic purposes (if indicated), but also to maximize exposure of the FOM and the posterior OC. In most cases, an upper neck dissection is performed prior to the combined approach to allow exposure of the external carotid branches, the lingual and the hypoglossal nerves, and the suprahyoid muscles. If oropharyngeal exposure is required, this may also be optimized by dissection of the lateral neck.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree