Surgical Technique

Akash Anand

M. Boyd Gillespie

Terry A. Day

INTRODUCTION

This section describes the various types of neck dissections and their standardized descriptions, along with the indications and risks for each when applied to squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract, melanoma, salivary gland malignancies, and thyroid carcinoma, respectively. Particular detail is provided for the most commonly performed neck dissections by the authors, which includes selective neck dissections (SNDs).

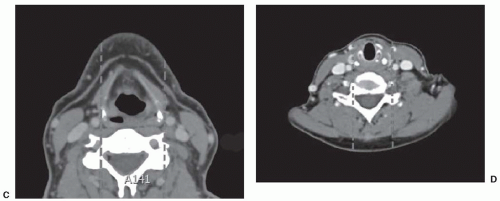

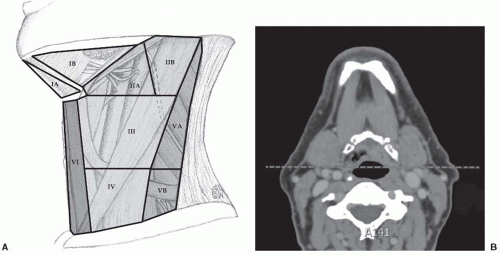

FIGURE 14-16. A: Clinical boundaries of the levels of the neck. B: Radiographic boundaries between IB and IIA are marked by a “vertical” line marked by the posterior edge of the submandibular gland.5 For demonstrative purposes, this is shown as dashed lines on an axial CT. C: Radiographic boundaries between levels III and VI are marked by a vertical line at the medial border of the common carotids.5 D: Radiographic boundaries between levels IV and VI are marked by a vertical line at the medial border of the common carotid arteries. |

Neck dissection for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is generally performed based upon (a) location of clinically evident nodal metastases and (b) the likelihood of occult metastatic disease in the various nodal levels based on primary site.1,2,3,4 (Fig. 14-16 depicts the clinical and radiographic boundaries of

the nodal levels of the neck.5) Based upon these factors, the authors generalize that at a minimum, when indicated, the follow lymph node levels should be considered for neck dissection and/or radiation therapy for selected sites:

the nodal levels of the neck.5) Based upon these factors, the authors generalize that at a minimum, when indicated, the follow lymph node levels should be considered for neck dissection and/or radiation therapy for selected sites:

Oral cavity: Levels I, II, III, and possibly IV (Fig. 14-17)

Oropharynx: Levels II, III, and IV (Fig. 14-18)

Hypopharynx: Levels II, III, and IV (Fig. 14-18)

Larynx: Levels II, III, IV, and possibly VI

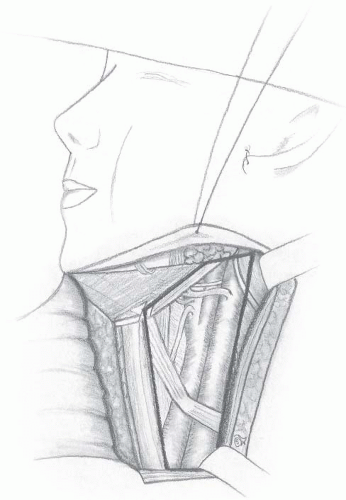

FIGURE 14-17. Sentinel node dissection I to III. (All contributions to the jugular vein are not shown.) |

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES

Selective Neck Dissection (Levels I, II, III, IV)

By far, the most common neck dissection performed today is the SND, in which only the nodal levels that are clinically positive, or have a significant possibility of harboring metastatic disease for a given primary site, are removed.6,7 The main advantage of this is a reduction in the morbidity that is associated with more extensive neck dissections.8,9 Of course, clinical judgment should always be used, and any levels clinically involved with disease should be addressed regardless of the primary site.

In cases where surgery is the primary modality of treatment and nodal disease is clinically present, or in cases where nodal disease is clinically present after the completion of nonsurgical treatment, it is accepted that a neck dissection that includes the positive nodes should be performed. A remaining controversy exists in the management of the N0 neck and in the postchemoradiation neck mass. Each subsite deserves separate consideration of these issues, taking into consideration the tendency of that particular site to harbor occult metastatic disease.

Though the entire field of study with regard to neck dissections is deficient in the number of prospective trials that have addressed the benefits of different types of neck dissections for different levels of disease, several retrospective studies have shown a survival benefit with elective neck dissection for patients who have oral cavity disease that is staged T2-T4N0 or is ≥4 mm in thickness, especially in the subsites of the maxillary gingiva, alveolus, or hard palate,10,11,12,13,14,15 though there have also been contrary reports.16,17 It is well known that regional recurrences in oral cavity cancers have a dismal chance of successful salvage, however, and at present, this knowledge seems to have led many surgeons to err on the side of caution and perform SNDs on early-staged cN0 oral cavity patients.

The SND that is most commonly used for oral cavity carcinoma includes removal of levels I, II, and III (Fig. 14-17), and consideration should be given to removal of facial lymph nodes when evidence of malignancy or enlarged nodes of this region is present. Additional indications for this procedure may include lip carcinoma, submandibular gland malignancy, and melanoma of the cheek, the lips, and adjacent areas. This technique is not sufficient or indicated for oropharyngeal, laryngeal, or hypopharyngeal malignancy.

The techniques described herein will include removal of levels I, II, and III, and implies that SND is separate from primary site resection. When the neck dissection and primary site are addressed at the same time, it is important to modify the technique slightly to confirm mobilization and preservation of vital structures while removing all tumor en bloc when possible.

Neck Incision Planning. The neck incision is usually marked and placed in a horizontal skin crease approximately two-finger breadths inferior to the mandible, but in a location adequate to expose the necessary lymph node levels. The neck incision is typically marked in a horizontal skin crease and may require an incision approximately 6 cm in length, although many surgeons continue to utilize an extension of the posterior aspect upward near the mastoid tip, and the anterior incision may continue across midline. The incision for most neck dissections can be limited to a horizontal incision in a skin crease, unless circumstances warrant an extension across midline, or extension of a vertical limb inferiorly for a radical neck dissection (RND), or superiorly, to include parotidectomy or extended neck dissection.

Incision. The authors advocate using a 15-blade scalpel for the skin incision and electocautery for the remainder of the procedure. The skin incision should be carried through the subcutaneous tissue to expose the platysma muscle. At this point, the electrocautery is used to divide the platysma muscle in an avascular plane. The platysma is dehiscent at the anterior and posterior edge of the incision, forcing the surgeon to be aware that the external jugular vein and greater auricular nerve will be exposed deep to the subcutaneous fat overlying the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM). These two structures are commonly preserved and provide excellent landmarks for the posterosuperior flap elevation.

Flap Elevation. Typically, double-pronged skin retractors are used by the assistant to retract the superior and inferior skin/platysma flap for elevation by the surgeon. The electrocautery is used to perform the flap elevation with adequate retraction and tension applied by the assistant. The superior flap is elevated to the level of the inferior border of the mandible, whereas the inferior flap is elevated to the level of the clavicle. Paralytic agents are avoided during this portion of the procedure to allow for identification and atraumatic dissection superiorly near the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve. Injury to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve can cause smile asymmetry secondary to decreased innervation of the depressor anguli oris and depressor labii inferioris muscles.18 If level I dissection is indicated, the marginal mandibular nerve is isolated, exposed, and retracted to remove level IB and lymphatics around these branches. If not, the fascia at the level of the hyoid bone or digastric muscle can be incised and mobilized to avoid injury to the marginal mandibular branch and expose the digastric muscle. Several small vessels are ligated with ligaclips, entering the skin flap during elevation, while electrocautery provides hemostasis for the other areas. During the superior flap dissection, the external jugular vein and greater auricular nerve can be dissected and isolated for preservation and form the deep extent of flap elevation.

Approach to Lymphatic Structures. Once the flaps are elevated and the fascia overlying the lymph node levels to be removed is exposed, the skin is retracted with elastic self-retaining skin hook retractors in four quadrants to allow the surgeon and assistant hands-free retraction and dissection of the lymphatics. It is important to note that if nodal disease is present or involving structures, the technique will require modification to avoid entering lymph nodes or their extracapsular component, and these areas should be removed “en bloc.”

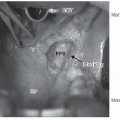

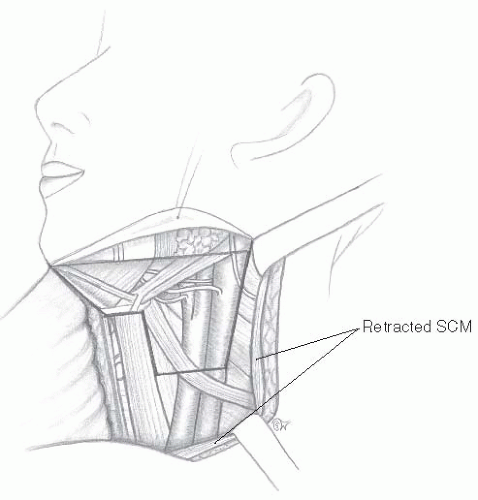

Lymphatic Dissection. The initial incision in the fascia is placed at the anterior border of the external jugular vein, the greater auricular nerve, and the SCM interface, and this fascia is then grasped with Allis forceps, thus providing tension and exposure to the anterior border of the SCM and levels II to IV. Using Babcock forceps on the SCM and Allis forceps on the lymphatics, the fascia and the lymphatics of levels II to IV are then freed from the anterior and deep aspect of the SCM, rounding the deep aspect of the SCM toward the deep and posterior border where cervical rootlets can then be exposed. It is crucial at this juncture to be aware that there is often a confluence of the greater auricular branch, and cervical branches 2 and 3, along with a communicating branch to the spinal accessory nerve that do not present themselves except near the posterior border of the SCM. After the skin flaps are elevated, the anterior and posterior border of the digastric muscle is exposed along with the SCM, the greater auricular nerve, the external jugular vein, and the omohyoid muscle, which are all preserved when oncologically indicated. The skin, muscles, and surrounding tissues can be retracted throughout the case with elastic self-retaining retractors. We will briefly separate the dissection of levels II, III, and IV to incorporate unique challenges of the anatomy of each level.

Level I. See Radical Neck Dissection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree